SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load in Upper Respiratory Specimens of Infected Patients (original) (raw)

To the Editor: The 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) epidemic, which was first reported in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, and has been declared a public health emergency of international concern by the World Health Organization, may progress to a pandemic associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. SARS-CoV-2 is genetically related to SARS-CoV, which caused a global epidemic with 8096 confirmed cases in more than 25 countries in 2002–2003.1 The epidemic of SARS-CoV was successfully contained through public health interventions, including case detection and isolation. Transmission of SARS-CoV occurred mainly after days of illness2 and was associated with modest viral loads in the respiratory tract early in the illness, with viral loads peaking approximately 10 days after symptom onset.3 We monitored SARS-CoV-2 viral loads in upper respiratory specimens obtained from 18 patients (9 men and 9 women; median age, 59 years; range, 26 to 76) in Zhuhai, Guangdong, China, including 4 patients with secondary infections (1 of whom never had symptoms) within two family clusters (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org). The patient who never had symptoms was a close contact of a patient with a known case and was therefore monitored. A total of 72 nasal swabs (sampled from the mid-turbinate and nasopharynx) (Figure 1A) and 72 throat swabs (Figure 1B) were analyzed, with 1 to 9 sequential samples obtained from each patient. Polyester flock swabs were used for all the patients.

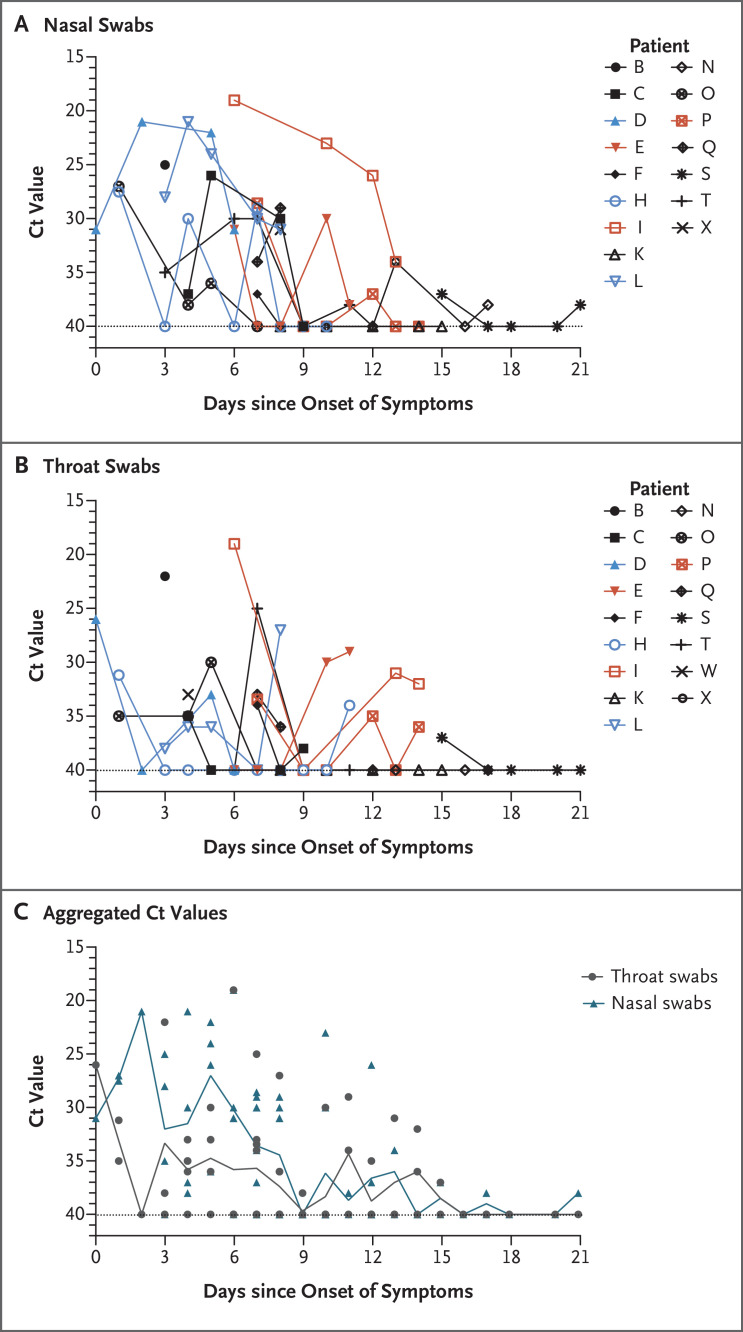

Figure 1. Viral Load Detected in Nasal and Throat Swabs Obtained from Patients Infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Panel A shows cycle threshold (Ct) values of Orf1b on reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) assay that were detected in nasal swabs obtained from 14 patients with imported cases and 3 patients with secondary cases, and Panel B shows the Ct values in throat swabs. Patient Z did not have clinical symptoms and is not included in the figure. Patients with imported cases who had severe illness (Patients E, I, and P) are labeled in red, patients with imported cases who had mild-to-moderate illness are labeled in black, and patients with secondary cases (Patients D, H, and L) are labeled in blue. A linear mixed-effects model was used to test the Ct values from nasal and throat swabs among severe as compared with mild-to-moderate imported cases, which allowed for within-patient correlation and a time trend of Ct change. The mean Ct values in nasal and throat swabs obtained from patients with severe cases were lower by 2.8 (95% confidence interval [CI], −2.4 to 8.0) and 2.5 (95% CI, −0.8 to 5.7), respectively, than the values in swabs obtained from patients with mild-to-moderate cases. Panel C shows the aggregated Ct values of Orf1b on RT-PCR assay in 14 patients with imported cases and 3 patients with secondary cases, according to day after symptom onset. Ct values are inversely related to viral RNA copy number, with Ct values of 30.76, 27.67, 24.56, and 21.48 corresponding to 1.5×104, 1.5×105, 1.5×106, and 1.5×107 copies per milliliter. Negative samples are denoted with a Ct of 40, which was the limit of detection.

From January 7 through January 26, 2020, a total of 14 patients who had recently returned from Wuhan and had fever (≥37.3°C) received a diagnosis of Covid-19 (the illness caused by SARS-CoV-2) by means of reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction assay with primers and probes targeting the N and Orf1b genes of SARS-CoV-2; the assay was developed by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Samples were tested at the Guangdong Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Thirteen of 14 patients with imported cases had evidence of pneumonia on computed tomography (CT). None of them had visited the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan within 14 days before symptom onset. Patients E, I, and P required admission to intensive care units, whereas the others had mild-to-moderate illness. Secondary infections were detected in close contacts of Patients E, I, and P. Patient E worked in Wuhan and visited his wife (Patient L), mother (Patient D), and a friend (Patient Z) in Zhuhai on January 17. Symptoms developed in Patients L and D on January 20 and January 22, respectively, with viral RNA detected in their nasal and throat swabs soon after symptom onset. Patient Z reported no clinical symptoms, but his nasal swabs (cycle threshold [Ct] values, 22 to 28) and throat swabs (Ct values, 30 to 32) tested positive on days 7, 10, and 11 after contact. A CT scan of Patient Z that was obtained on February 6 was unremarkable. Patients I and P lived in Wuhan and visited their daughter (Patient H) in Zhuhai on January 11 when their symptoms first developed. Fever developed in Patient H on January 17, with viral RNA detected in nasal and throat swabs on day 1 after symptom onset.

We analyzed the viral load in nasal and throat swabs obtained from the 17 symptomatic patients in relation to day of onset of any symptoms (Figure 1C). Higher viral loads (inversely related to Ct value) were detected soon after symptom onset, with higher viral loads detected in the nose than in the throat. Our analysis suggests that the viral nucleic acid shedding pattern of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 resembles that of patients with influenza4 and appears different from that seen in patients infected with SARS-CoV.3 The viral load that was detected in the asymptomatic patient was similar to that in the symptomatic patients, which suggests the transmission potential of asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients. These findings are in concordance with reports that transmission may occur early in the course of infection5 and suggest that case detection and isolation may require strategies different from those required for the control of SARS-CoV. How SARS-CoV-2 viral load correlates with culturable virus needs to be determined. Identification of patients with few or no symptoms and with modest levels of detectable viral RNA in the oropharynx for at least 5 days suggests that we need better data to determine transmission dynamics and inform our screening practices.

Supplementary Appendix

Disclosure Forms

This letter was published on February 19, 2020, and updated on February 20, 2020, at NEJM.org.

Ms. Zou, Mr. Ruan, and Dr. Huang contributed equally to this letter.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004 (https://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/table2004_04_21/en/).

- 2.Lipsitch M, Cohen T, Cooper B, et al. Transmission dynamics and control of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science 2003;300:1966-1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peiris JSM, Chu CM, Cheng VCC, et al. Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: a prospective study. Lancet 2003;361:1767-1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsang TK, Cowling BJ, Fang VJ, et al. Influenza A virus shedding and infectivity in households. J Infect Dis 2015;212:1420-1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, et al. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med 2020;382:970-971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.