Distinct Affinity of Binding Sites for S-Layer Homologous Domains in Clostridium thermocellum and Bacillus anthracis Cell Envelopes (original) (raw)

Abstract

Binding parameters were determined for the SLH (S-layer homologous) domains from the Clostridium thermocellum outer layer protein OlpB, from the C. thermocellum S-layer protein SlpA, and from the Bacillus anthracis S-layer proteins EA1 and Sap, using cell walls from C. thermocellum and B. anthracis. Each SLH domain bound to C. thermocellum and B. anthracis cell walls with a different KD, ranging between 7.1 × 10−7 and 1.8 × 10−8 M. Cell wall binding sites for SLH domains displayed different binding specificities in C. thermocellum and B. anthracis. SLH-binding sites were not detected in cell walls of Bacillus subtilis. Cell walls of C. thermocellum lost their affinity for SLH domains after treatment with 48% hydrofluoric acid but not after treatment with formamide or dilute acid. A soluble component, extracted from C. thermocellum cells by sodium dodecyl sulfate treatment, bound the SLH domains from C. thermocellum but not those from B. anthracis proteins. A corresponding component was not found in B. anthracis.

The sequences of many bacterial cell surface proteins contain a conserved region termed the SLH (S-layer homologous) domain (7) which is composed of about 50- to 60-amino-acid segments usually reiterated threefold. SLH domains were shown to mediate binding of exocellular proteins to the cell surface in vivo and in vitro. In vivo, a mutant of Thermus thermophilus in which the SLH domain of the S-layer protein was deleted produced an S-layer which no longer bound to the cell surface (11). In vitro, the SLH domains of the Clostridium thermocellum outer layer protein OlpB and of the C. thermocellum S-layer protein SlpA bound to cell wall preparations (4, 5). The mode of attachment of SLH domains to the cell wall in Bacillus stearothermophilus PV72/p2 was proposed to be mediated by a secondary cell wall polysaccharide containing _N_-acetylglucosamine and _N_-acetylmannosamine in a molar ratio of 4:1 (12). In C. thermocellum, SLH domains were shown to bind not only to cell walls but also to a soluble cell envelope component which could be extracted by treating cells with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) at 100°C (5). In this report, we compare the SLH-binding properties of cell envelope components from Bacillus subtilis, C. thermocellum, and Bacillus anthracis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Wild-type C. thermocellum NCIB 10682 was grown anaerobically, at 60°C and without stirring, in complete CM3-3 medium (16) containing 5 g of cellobiose (Fluka AG) per liter. The B. anthracis plasmidless strain 9131, which is devoid of a capsule (1), and the B. subtilis wild-type strain JH642 (from J. A. Hoch) were grown aerobically at 37°C in LB medium (8). Escherichia coli TG1 (2), M15(pREP4) (18), and BL21(pREP4) (15) were used as cloning hosts and were grown at 37°C in LB medium. Ticarcillin (100 μg/ml) and kanamycin (25 μg/ml) were added, depending on the plasmids present in the host.

Preparation of SLH polypeptides derived from C. thermocellum OlpB and SlpA and from B. anthracis EA1 and Sap.

MalE-OlpB1391-1664 (formerly termed MalE-ORF1p-C; (subscript numbers denote amino acids encompassed by the indicated protein) and SlpA27-235 were purified from E. coli TG1(pCT1473) and E. coli M15(pREP4) harboring pCT1923, respectively, as described previously (4, 5). The expression plasmids pQE1473, pQEEA1, and pQESAP were obtained by subcloning appropriate restriction or PCR fragments into pQE30 or pQE31 (Qiaexpress kit; Qiagen). OlpB1391-1664 and EA132-213 were purified from E. coli BL21(pREP4) harboring pQE1473 and pQEEA1, respectively, and Sap32-211 was purified from E. coli M15(pREP4) harboring pQESAP. Each of the overproduced polypeptides was fused to six N-terminal His residues encoded by the vector, enabling purification by Ni2+ affinity chromatography (3) as described previously (4). For purification of EA132-213 and Sap32-211 polypeptides, 40 mM imidazole was added to the wash buffer.

Cell wall preparation.

Cell walls were isolated as described by Lemaire et al. (5). Briefly, whole cells were treated twice with boiling SDS and sonicated, and the pelleted insoluble material was treated once again with boiling SDS. The resulting cell wall preparation was washed five times with 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5). The _meso_-diaminopimelate content, which is proportional to peptidoglycan content, was determined for each cell wall preparation by acid hydrolysis followed by amino acid analysis (5).

Affinity of SLH polypeptides for cell walls.

Each SLH polypeptide was incubated at various concentrations (40 to 240 μg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C with shaking in 100 μl of 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing cell walls from C. thermocellum (containing 34.6 μM _meso_-diaminopimelate) or B. anthracis (containing 97.3 μM _meso_-diaminopimelate). For B. subtilis, cell walls (containing 251.5 μM _meso_-diaminopimelate) were incubated in the presence of 20 μg of each SLH polypeptide. Free SLH polypeptides were separated from bound SLH polypeptides by centrifugation twice at 40,000 × g for 20 min. The concentration of free SLH polypeptide was assayed in the pooled supernatants by using the micro bicinchoninic acid protein assay reagents (Pierce). The total amount of polypeptide present in the resuspended pellet fraction was assayed with the Coomassie blue reagent (Bio-Rad). The amount of bound SLH polypeptide was calculated by subtracting the amount of free SLH polypeptide remaining in the pellet suspension. Colorimetric determinations were converted to molar concentrations by reference to a standard consisting of a stock of the same polypeptide whose molarity was determined by UV absorption at 280 nm. Data points were fitted with one-site binding-type hyperbolas by nonlinear regression using the Prism program (GraphPad).

Effect of various extraction procedures on the SLH-binding ability of C. thermocellum cell walls.

SDS-extracted cell walls were washed four times with distilled water and vacuum dried. Aliquots were then treated with formamide for 1 h at 100 or 150°C, with 25 mM glycine-HCl (pH 2.5) for 0.5 h at 100°C, with 0.1 M HCl for 0.5 h at 60°C, or with 48% hydrofluoric acid (HF) for 22 h at 4°C and finally washed with distilled water (12). Binding of MalE-OlpB1391-1664 to native or treated cell walls was tested as described previously (5). After incubation in the presence of cell walls, bound and free polypeptides were separated by centrifugation. The supernatant constituted the soluble fraction. A wash fraction was obtained after washing cell walls with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). The insoluble fraction consisted of material eluted from cell walls in the presence of hot SDS. Each fraction was analysed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Binding of SLH polypeptides to the SDS-soluble component of C. thermocellum cell envelopes.

C. thermocellum cells were treated for 15 min with SDS at 100°C, and the extracted material was subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (5). Following transfer to nitrocellulose, blots were incubated with 125I-labeled SLH polypeptides and autoradiographed (17).

RESULTS

Parameters of binding of different SLH domains to cell walls from B. subtilis, C. thermocellum, and B. anthracis.

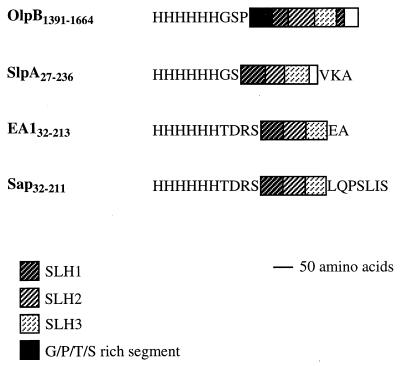

Four different SLH polypeptides were tested for binding to cell walls of B. subtilis, C. thermocellum, or B. anthracis (Fig. 1). OlpB1391-1664 corresponds to the C-terminal region of the C. thermocellum outer layer protein OlpB (5). SlpA27-235 contains the N-terminal SLH domain of the C. thermocellum S-layer protein SlpA (4). EA132-213 and Sap32-211 correspond to the N-terminal SLH domains of the two S-layer proteins EA1 and Sap of B. anthracis (1, 10). Binding was estimated from the amount of polypeptide cosedimenting with a known amount of cell walls, normalized for its content in _m_-diaminopimelate. The cell wall preparations consisted mostly of peptidoglycan and contained no significant amount of covalently associated protein.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of SLH polypeptides purified from E. coli. The triplicated segments of SLH domains extending between amino acids indicated by the numbers are shown by boxes. Amino acids encoded by the expression vector are indicated. The SLH domain of OlpB carries a circular permutation (6), resulting in the location of the N-terminal part of the first SLH segment at the C terminus of the third SLH segment.

The quantities of OlpB1391-1664, SlpA27-235, EA132-213, and Sap32-211 polypeptides cosedimenting with B. subtilis cell walls amounted to less than 2 mmol/mol of _meso_-diaminopimelate, indicating that B. subtilis cell walls do not have binding sites for C. thermocellum or B. anthracis SLH domains.

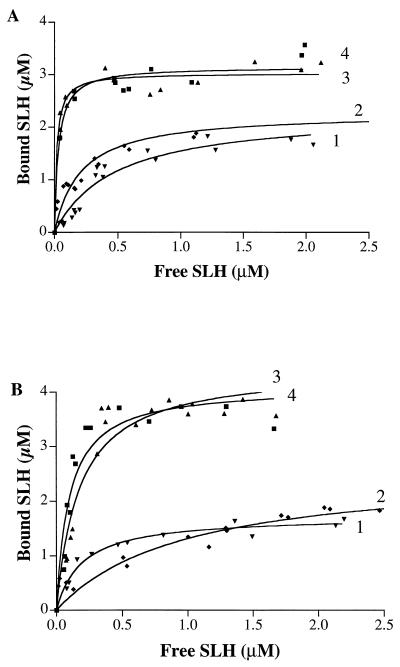

As shown in Fig. 2A and Table 1, C. thermocellum cell walls bound the C. thermocellum polypeptides OlpB1391-1664 and SlpA27-235 with the same capacity but with a 2.3-fold-higher affinity for SlpA27-235 than for OlpB1391-1664. B. anthracis polypeptides EA132-213 and Sap32-211 both were bound by C. thermocellum cell walls with a 1.4-fold-higher capacity and affinities that were an order of magnitude higher than observed for C. thermocellum polypeptides, the highest value being obtained for EA132-213 (KD = 1.8 × 10−8 M).

FIG. 2.

Binding of SLH domains to cell walls of C. thermocellum containing 34.6 μM _meso_-diaminopimelate (A) and to cell walls of B. anthracis containing 97.3 μM _meso_-diaminopimelate (B). Curve 1, OlpB1391-1664 (▾); curve 2, SlpA27-235 (⧫); curve 3, EA132-213 (▴); curve 4, Sap32-211 (■).

TABLE 1.

Parameters of binding of OlpB1391-1664, SlpA27-235, EA132-213, and Sap32-211 polypeptides to C. thermocellum and B. anthracis cell walls

| Protein | C. thermocellum cell walls | B. anthracis cell walls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KD (M) | Capacitya | KD (M) | Capacity | |

| OlpB1391-1664 | 4.8 × 10−7 ([2.7–6.9] × 10−7_b_) | 66 (55–78b) | 1.9 × 10−7 ([1.2–2.6] × 10−7) | 18 (16–19) |

| SlpA27-235 | 2.1 × 10−7 ([1.2–2.9] × 10−7) | 66 (58–74) | 7.1 × 10−7 ([3.7–10.4] × 10−7) | 24 (20–27) |

| EA132-213 | 1.8 × 10−8 ([1.0–2.6] × 10−8) | 88 (83–93) | 1.8 × 10−7 ([0.9–2.6] × 10−7) | 46 (40–51) |

| Sap32-211 | 3.1 × 10−8 ([1.7–4.6] × 10−8) | 91 (85–97) | 1.0 × 10−7 ([0.5–1.5] × 10−7) | 42 (36–48) |

B. anthracis cell walls displayed significant differences from C. thermocellum cell walls. The binding capacity was 1.8- and 2.4-fold (instead of 1.4-fold) greater for the B. anthracis than the C. thermocellum polypeptides (Fig. 2B and Table 1). The range of binding affinities was much narrower. In particular, KD values for OlpB1391-1664 and EA132-213 were similar, whereas they differed 27-fold in the case of binding to C. thermocellum cell walls. Furthermore, the binding affinity increased in the order OlpB < SlpA < < Sap ≤ EA1 in the case of C. thermocellum cell walls, whereas for B. anthracis cell walls the order was SlpA < OlpB ∼ EA1 ∼ Sap.

Effects of different chemical treatments on the SLH-binding ability of C. thermocellum cell walls.

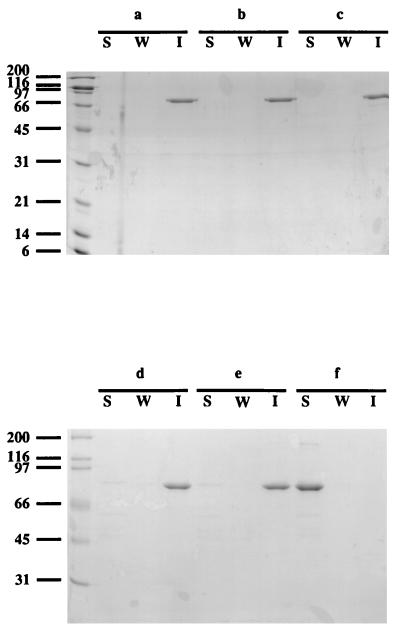

It was proposed that in B. stearothermophilus PV72/p2, adhesion to the cell wall of the S-layer protein SbsB, which contains an SLH domain, was mediated by a secondary cell wall polysaccharide (12). This polysaccharide, containing _N_-acetylglucosamine and _N_-acetylmannosamine in a molar ratio of 4:1, could be extracted with dilute acid, formamide, or HF, leaving behind a peptidoglycan fraction which no longer bound SbsB. The same extraction procedures were applied to C. thermocellum cell walls, which were subsequently tested for the ability to bind MalE-OlpB1391-1664, containing the SLH domain of OlpB grafted to MalE (5). As shown in Fig. 3, treatment with formamide (at 100 or 150°C) or with dilute acid (25 mM glycine-HCl [pH 2.5] or 0.1 M HCl) did not impair the ability of cell walls to bind MalE-OlpB1391-1664. However, MalE-OlpB1391-1664 no longer cosedimented with cell walls treated with 48% HF, showing that SLH binding was abolished. The HF-extracted material was analyzed for hexoses (14) after hydrolysis with 4 N trifluoroacetic acid for 4 h, yielding _N_-acetylglucosamine, glucose, galactose, and _N_-acetylmannosamine in a molar ratio of 1:6.4:1.9:0.27.

FIG. 3.

Binding of MalE-OlpB1391-1664 to C. thermocellum cell walls subjected to various extraction procedures. Native cell walls (a) were treated with formamide at 100°C (b) or 150°C (c), with 25 mM glycine-HCl (pH 2.5) (d), with 0.1 M HCl (e), or with 48% HF (f). Lanes: S, soluble fraction; W, wash fraction; I, insoluble fraction. The leftmost lane shows positions of molecular size markers (in kilodaltons).

Binding of SLH domains to components noncovalently linked to cell walls.

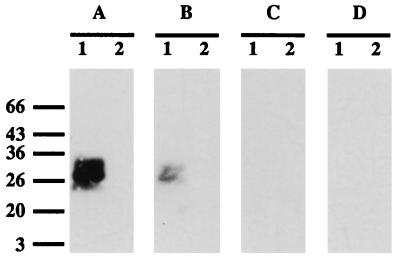

As shown previously (5), a soluble component which binds the SLH domain of OlpB can be extracted from the surface of C. thermocellum by boiling cells in SDS. This component migrates in SDS-polyacrylamide gels like a 26/28-kDa polypeptide doublet. However, it is probably not a protein, since it is not extracted by phenol-chloroform and cannot be degraded with proteinase K or pronase (data not shown). Contrary to SLH-binding sites remaining on C. thermocellum cell walls treated with SDS, the 26/28-kDa component was sensitive to dilute acid (25 mM glycine-HCl buffer [pH 2.5]) (data not shown). Binding of the SLH domain of OlpB to the SDS-soluble component was demonstrated by transferring the component from SDS-polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose and by incubating the blots with 125I-labeled MalE-OlpB1391-1664 (5). The same experiment was performed with OlpB1391-1664, SlpA27-235, EA132-213, and Sap32-211 polypeptides as 125I-labeled probes. Figure 4 shows that the 26/28-kDa doublet bound OlpB1391-1664 or SlpA27-235 but neither EA132-213 nor Sap32-211. To test whether a similar component could be detected in B. anthracis, the same experiment was repeated with SDS extracts of B. anthracis cells. No band was revealed with any of the 125I-labeled polypeptides (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Binding of OlpB1391-1664 (A), SlpA27-235 (B), EA132-213 (C), or Sap32-211 (D) polypeptides labeled with 125I to the SDS-soluble component extracted from C. thermocellum (lane 1) or B. anthracis (lane 2). The masses (in kilodaltons) and positions of migration of molecular size markers are indicated on the left.

DISCUSSION

Taken together, our results suggest that SLH-binding sites are different in different bacterial species and are not unique within the same species. Cell walls from C. thermocellum and B. anthracis can bind SLH domains from both bacteria, suggesting similar modes of interaction of SLH domains. However, comparison of binding parameters shows that SLH-binding sites are different in C. thermocellum and B. anthracis. None of the four SLH domains tested had the same affinity for cell walls from C. thermocellum and B. anthracis, and the binding specificities of the two cell wall preparations were different. Moreover, the different binding capacities of each cell wall preparation for different SLH polypeptides suggest that some SLH-binding sites are accessible to B. anthracis SLH domains but not to C. thermocellum SLH domains.

In addition to the SLH-binding sites of the SDS-insoluble cell walls, the envelope of C. thermocellum contains an SDS-soluble component that binds SLH domains (5). In contrast to C. thermocellum cell walls, it is not able to bind the SLH domains from the B. anthracis S-layer proteins EA1 and Sap. No similar component could be extracted from B. anthracis cells, suggesting that it is specific for C. thermocellum.

The SLH-binding site which is soluble in SDS is noncovalently linked to the cell wall. This finding is compatible with the hypothesis that this component may be located within the outer layer surrounding the S-layer of C. thermocellum. Indeed, OlpB, which was shown to be located in the outer layer (5), interacted more strongly with the SDS-soluble component but more weakly with cell walls than SlpA which was localized in the cell wall-associated S-layer (4). Thus, the presence of SLH-binding components with different specificities may afford the possibility for the bacterium to target exocellular proteins to different locations on the bacterial cell surface.

Cell walls of B. subtilis did not contain detectable binding sites for SLH domains. This is not unexpected, since sequence analysis of the B. subtilis genome did not reveal any gene putatively encoding a cell surface polypeptide containing an SLH domain. Therefore, SLH-binding components are probably restricted to the cell surface of bacteria secreting cell-associated proteins which carried SLH domains.

Our results strongly suggest that a secondary cell wall polymer is responsible for binding SLH domains to C. thermocellum cell walls. Treatment of C. thermocellum cell walls with 48% HF abolished binding of the SLH domain of OlpB, suggesting that a secondary polysaccharide may be involved. Indeed, material containing _N_-acetylglucosamine, glucose, galactose, and _N_-acetylmannosamine was found in the HF extract which may correspond, in part, to the binding target of SLH domains. A similar effect of HF on the SLH-binding capacity of B. anthracis cell walls has been reported (9). Conflicting data were reported for the binding of the S-layer protein SbsB to cell walls of B. stearothermophilus PV72/p2. Treatment of B. stearothermophilus cell walls with HF was reported to abolish binding of SbsB and to extract a polysaccharide composed of _N_-acetylglucosamine and _N_-acetylmannosamine in a 4:1 molar ratio. The latter component was shown to bind to SbsB (12). More recently, it was reported that SbsB binds to HF-extracted B. stearothermophilus cell walls, provided that its SLH domain is intact (13). If confirmed, this finding suggests that SLH domains may have yet a different binding target (i.e., pure peptidoglycan) in B. stearothermophilus. Further studies with purified SLH-binding components will be required to understand the molecular basis for the affinity and specificity of interaction between SLH domains and their binding targets.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Mesnage and A. Fouet (Unité des Toxines et Pathogénie Bactériennes, Institut Pasteur) for providing the B. anthracis strain and critical review of the manuscript. F. Baleux (Unité de Chimie Organique, Institut Pasteur) and T. Fontaine (Laboratoire des Aspergillus, Institut Pasteur) are acknowledged for cell wall and sugar analysis, respectively. We are grateful to I. Miras for providing samples of the SlpA SLH domain.

M.M. was the recipient of a TMR Marie Curie Research Training Grant, contract ERBFMBICT961549 from the Commission of the European Communities.

REFERENCES

- 1.Etienne-Toumelin I, Sirard J C, Duflot E, Mock M, Fouet A. Characterization of the Bacillus anthracis S-layer: cloning and sequencing of the structural gene. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:614–620. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.3.614-620.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibson T J. Studies on the Epstein-Barr virus genome. Ph.D. thesis. Cambridge, England: University of Cambridge; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janknecht R, de Martynoff G, Lou J, Hipskind R A, Nordheim A, Stunnenberg H G. Rapid and efficient purification of native histidine-tagged protein expressed by recombinant vaccinia virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8972–8976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.8972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemaire M, Miras I, Gounon P, Béguin P. Identification of a region responsible for binding to the cell wall within the S-layer protein of Clostridium thermocellum. Microbiology. 1998;144:211–217. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-1-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lemaire M, Ohayon H, Gounon P, Fujino T, Béguin P. OlpB, a new outer layer protein of Clostridium thermocellum, and binding of its S-layer-like domain to components of the cell envelope. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2451–2459. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.9.2451-2459.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lupas A. A circular permutation event in the evolution of the SLH domain? Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:897–898. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lupas A, Engelhardt H, Peters J, Santarius U, Volker S, Baumeister W. Domain structure of the Acetogenium kivui surface layer revealed by electron crystallography and sequence analysis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1224–1233. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.5.1224-1233.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mesnage S, Tosi-Couture E, Fouet A. Expression and cell surface anchoring of functional Bacillus subtilis levansucrase fused to the SLH motifs of the Bacillus anthracis S-layer proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:927–936. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mesnage S, Tosi-Couture E, Mock M, Gounon P, Fouet A. Molecular characterization of the Bacillus anthracis main S-layer component: evidence that it is associated with the major cell-associated antigen. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:1147–1155. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2941659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olabarría G, Carrascosa J L, de Pedro M A, Berenguer J. A conserved motif in S-layer proteins is involved in peptidoglycan binding in Thermus thermophilus. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4765–4772. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4765-4772.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ries W, Hotzy C, Schocher I, Sleytr U B, Sára M. Evidence that the N-terminal part of the S-layer protein from Bacillus stearothermophilus PV72/P2 recognizes a secondary cell wall polymer. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3892–3898. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.3892-3898.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sára M, Egelseer E M, Dekitsch C, Sleytr U B. Identification of two binding domains, one for peptidoglycan and another for a secondary cell wall polymer, on the N-terminal part of the S-layer protein SbsB from Bacillus stearothermophilus PV72/p2. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6780–6783. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6780-6783.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sawardeker J S, Sloneker J H, Jeanes A. Quantitative determination of monosaccharides as their alditol acetates by gas liquid chromatography. Anal Chem. 1967;37:1602–1604. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Studier F W, Moffatt B A. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J Mol Biol. 1986;189:113–130. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tailliez P, Girard H, Millet J, Béguin P. Enhanced cellulose fermentation by an asporogenous and ethanol-tolerant mutant of Clostridium thermocellum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:207–211. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.1.207-211.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tokatlidis K, Salamitou S, Béguin P, Dhurjati P, Aubert J-P. Interaction of the duplicated segment carried by Clostridium thermocellum cellulases with cellulosome components. FEBS Lett. 1991;291:185–188. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81279-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villarejo M R, Zabin I. β-Galactosidase from termination and deletion mutant strains. J Bacteriol. 1974;120:466–474. doi: 10.1128/jb.120.1.466-474.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]