Walbert’s Compendium (original) (raw)

The New York Times reports on a new chatbot intended to combat conspiracy theories:

DebunkBot, an A.I. chatbot designed by researchers to “very effectively persuade” users to stop believing unfounded conspiracy theories, made significant and long-lasting progress at changing people’s convictions, according to a study published on Thursday in the journal Science.

The bot uses “facts and logic” to combat conspiracy theories, and in the study had some success in arguing people out of beliefs that, for example, the CIA killed JFK or 9/11 was an inside job. I do believe that most people, if guided onto a field of factual argument, can be convinced by facts and logic; the trouble is that people who hold opinions dearly may take any attempt to guide them as a personal attack. It may be that a bot, by seeming neutral and objective, may have more success.

Ah, but is the bot, in fact, neutral and objective? Specifically, what counts as a conspiracy theory? The invitation to participate in the study defines a conspiracy theory as a belief that “certain significant events or situations are the result of secret plans by individuals or groups.” But this is literally and incontrovertibly true of, for example, the JFK assassination, not to mention 9/11. Had the plans for those events not been secret, they would have been prevented! People who say 9/11 was an inside job are just arguing about which individuals or groups did the secret planning. They may be wrong, they may be nuts — but not, by this definition, because they’re conspiracy theorists.

So, this “stuck culture” thing that people keep talking about. People’s notion of normal is deeply screwed up.

The baseline—what “culture” seems to be “stuck” by comparison with—is a rapid turnover of fashions made possible by wealth and mass media. Wealth to afford new stuff all the time, mass media to disseminate fashions quickly. In one of Thomas Hardy’s novels, I believe (though can’t recall which one) he observes that while London fashions turned over every year, his rural characters wore essentially the same clothes as their 16th-century ancestors. Many folk songs recorded in 1920s Appalachia had roots traceable to the Elizabethan era. Even the “Classical Era” of music lasted nearly a century. Before the 19th century, even for the relatively wealthy, fashion turned far more slowly; for the 99% it turned on a scale of centuries.

Then came mass production, of course. But also magazines, made possible by cheaper printing, and with them the need to continually think up new stuff to publish. New dress patterns. New recipes. New stories. New ideas. The wheel of fashion accelerated. The possibilities of music publishing and the mass manufacture of pianos brought a continual demand for new music to play, and an industry that stoked that demand. Then came records, and radio, movies, and television. Each new invention disseminated new ideas faster; each required a greater source of new ideas to disseminate. The wheel spun ever faster. So that now, we are surprised to find that everybody is wearing pretty much the same clothes and listening to more or less the same music as they were ten or twenty years ago.

But that sort of rapid cultural change—which we now think of as normal—is a product of particular dominant technologies. Technologies that both enabled rapid change and required it, in order to exist—which is to say, to continue to make money for the people that created them. All were, in their way, building blocks of what is now sometimes called the attention economy.

Pawley’s Island, South Carolina, 21 August 2017

On the beach, the waves

break over laughing children

as on any afternoon.

“It’s only one thing passing

in front of another,” I say, and you laugh

though we both know better. Anxiously

we scan the heavens.

We know what to expect. We’ve seen

the pictures, timed it to the second.

We’ve planned this trip for months.

We bought our paper optics early.

We wear our commemorative t-shirts.

Along the shore, the upturned faces

measure shadow’s progress, check

the time. Mothers adjust their children’s

glasses. Amateur professors

lecture barefoot. A girl in a bikini

and a welder’s helmet like a

naked stormtrooper stalks

the sand. The man beside us

with elaborate equipment films

the cosmos, as if heaven might be rewound.

We have not gathered here for mere mechanics.

What do we seek, we scientific pilgrims?

Our eyes blacked out

admit only the brightest marvels.

Now gray like age

descends without the royal

tones of nightfall. Only the sun

still wears its crown, revealed

in death. The birds, uneducated,

fly for unbuilt dunes, and safety.

Reluctantly the day

resumes. Neighbors disengage,

settle into chairs. The birds

turn to their fishing.

You open your novel, I

my crossword, and a beer. Time slips

by once more unseen, and we,

baptized by darkness, go on living.

Make y’all of winter what you will:

The pine trees, tufted like old men’s ears,

The disappearing footprints of a sparrow,

Tire-tread slush translucent in the sun.

Global warming? Honey, it’s the South.

One good sled run wears the track to mud,

But dogs and children, mittenless and yelping,

Wear it regardless, gravelled snowballs pelting.

And if the wide-eyed wondering girl

Fat and frosty fingers in her mouth

Slurped her skyfall from a grimy fender

Bird-shat, bug-splattered beneath its sparkly splendor—

Let her father shrug, and drink his beer.

It isn’t much. It will be gone tomorrow.

Yesterday, out walking, I saw this little guy sunning himself on the sidewalk:

Apologies for the poor focus: I didn’t want to get too close until I was sure it wasn’t a copperhead. But I had to get sorta close, and even then I wasn’t sure of myself. The head was wrong, the pattern was wrong, it was quite small. But it might have been a baby.

So I pulled out my phone and opened one of the few apps that I would really miss if I switched back to a flip phone: Seek by iNaturalist. Point your camera at a living thing and it will tell you, given a reasonably good view, what species you are looking at. I got it when I was hiking out in the mountains a few years ago; it’s great for identifying wildflowers and trees in unfamiliar ecosystems. But it’s also great for figuring out what’s going on in the square mile I live in.

Earlier this year, having had my front yard ripped up to lay a new sewer line and finding myself on the cusp of summer, I tossed out a couple packets of mixed flower seed and figured whatever happened, happened. Now something is happening, but I don’t know what. I think I kept the seed packets, but where? And which flower is which? Sheepishly I pulled out my phone and resorted to using an app to tell me what I was growing myself. (Answer so far: Borage, two colors of garden balsam, pot marigolds, and some sort of blanket flower.)

Really, I ought to know this stuff. I ought to know all my local trees and flowers, and I ought to know my snakes. In fact I know an awful lot of them, but I’ve had to learn the hard way, by using field guides and websites, because nobody educated me properly when I was a kid. (That was in a different part of the country anyway, but nobody educated me properly there either.) I say this in all seriousness despite twenty years of formal schooling. Half the time I don’t know what’s going on under my nose, and I need an app to figure it out. My education was bullshit.

On Micro.Blog @jabel (Jeremy) has been writing about so-called “artificial intelligence” (SCAI for short, my abbreviation) through the lens of Ivan Illich’s Tools for Conviviality. It’s a matter worth taking seriously, and I always appreciate anybody reaching for Ivan Illich, even if I find his work equal parts useful and maddening. For economy, and because it has been awhile since I read Illich, I’ll borrow Jeremy’s quotes from Illich defining conviviality. In a convivial society there is “autonomous and creative intercourse among persons, and intercourse of persons with their environment. … [Conviviality is] individual freedom realized in personal interdependence.” Convivial tools therefore afford people “the freedom to make things among which they can live, to give shape to them according to their own tastes, and to put them to use in caring for and about others.”

By contrast, as Jeremy explains,

the failure of the industrial model of tools is rooted in a key error: namely, that we could make tools that work n behalf of humanity. That, in fact, we could replace human slaves with tool slaves. But we have found that when we replace human slaves with tool slaves, we become enslaved to the tools. Once tools grow beyond their natural scale, they begin shaping their users. The bounds of the possible become defined by the capabilities of the tools.

On one use of SCAI, Jeremy writes:

I think everyone would agree that old-fashioned encyclopedias are convivial tools, i.e., they facilitate autonomous human creativity; they can be picked up and put down at will; they make very few demands upon humans, etc. Search engines, as such, can also be convivial tools in that they are faster, digitized versions of encyclopedias. AI-assisted search might also be convivial in some ways.

The question of whether something like SCAI can be convivial is tempting, but I think it’s a mistake to address it head-on. Instead I want to respond to the first sentence in this paragraph, about “old-fashioned encyclopedias.” In part I want to do this because I am incapable of reading the phrase “I think we can all agree that” without instantly, unconsciously searching for a way to disagree. But in part it may be a useful way of nibbling up to the actual problem of SCAI.

A year or so ago I read The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber and David Wengrow. At the time I jotted down a few notes, and it has taken me this long, I’m afraid, to beat them into something like coherence. Hey, it’s about 40,000 years of human history: what’s another thirteen months?

I won’t attempt a summary or a proper review; for an overview of the work I recommend this review from Science News.

The authors observe, from archaeological and historical evidence, that humans long ago constituted their societies in a dazzling variety of ways, and indeed reconstituted themselves thoughtfully, deliberately, and relatively often, perhaps to ward off inequality or escape an authoritarian system. As my own study of history goes back only a few hundred years professionally and at most a thousand years in amateur terms, I’m not in a position to disagree with anyone’s meta-analysis of archaeological evidence. I do worry that it reads like a book heavily informed by, and perhaps at least partly driven by, present political concerns, but that doesn’t mean it’s necessarily wrong, only that I’m wary.

I do, however, want to dissent from the authors’ optimism—that is, their belief that if our ancestors thought creatively about politics and radically changed their situations, we ought to be able to do the same. We are limited, structurally, in ways our ancestors could not. They could pack up and leave a society they didn’t like: we can’t, for there are no longer any margins to speak of. They could play with agriculture for millennia without domesticating their crops and inducing mutual dependence, but that genie is out of the bottle now. I could go on.

Maybe the simplest objection is that what looks like a rapid change in deep history or the archaeological record may have seemed a terribly long time to those who lived through it. Reading about the sundry ways people have thoughtfully organized themselves in the past (and about how deliberately and thoughtfully they seem to have done so) gives me hope that, when this civilization falls and 99 percent of the people on the planet die, the remaining few will be able to come up with something better than Mad Max, indeed to lay a foundation for a far better future. But I’m not sure most people would consider that statement optimistic.

In any case, quibbling about hope and hopelessness is boring. So let’s talk about something else.

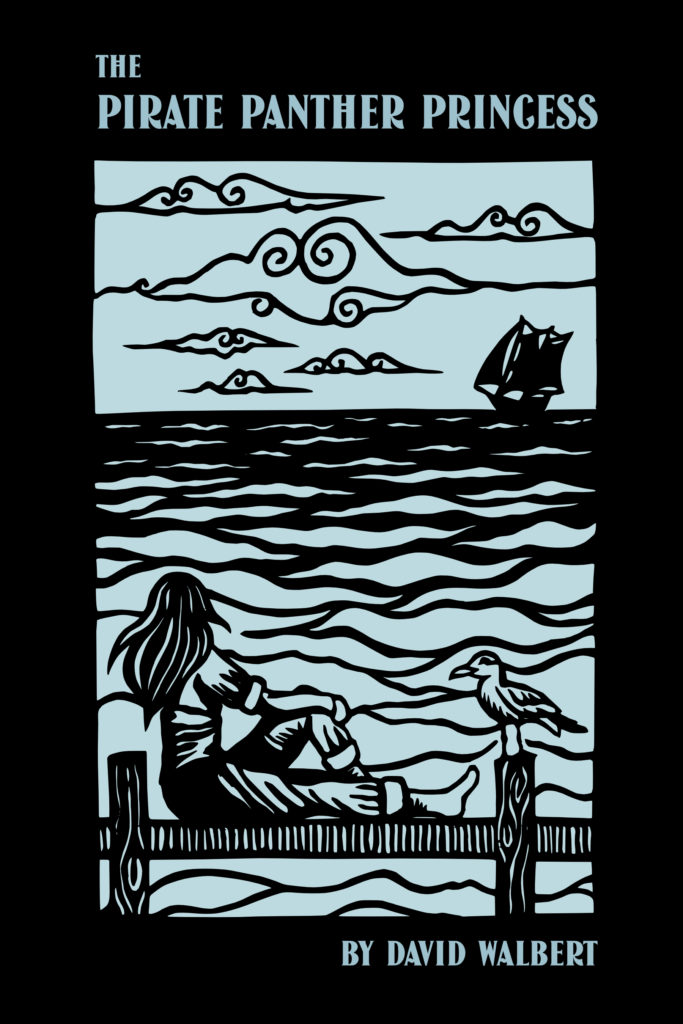

My long-awaited novel The Pirate Panther Princess is now available in print! For the time being, you can buy the softcover via print-on-demand. You can also read a free preview of the first six chapters.

A seaside civilization emerging from a long dark age…

Rough but noble traders who ply the coastal waters…

Brilliant makers renewing the world with their craft…

Black-hearted pirates with a ship that sails itself…

An evil prince who would rule the known world…

And a runaway girl lost at sea and struggling to survive who becomes a character in a folk tale and the unwitting hero of a revolution.

Though it will especially interest younger readers, there is much that will appeal to adults. The first six chapters will be available free at www.piratepantherprincess.com, so you can decide for yourself!

I’ll have more to say about the novel in January. A global edition available through retail booksellers may also be available early next year… if printing and paper costs don’t go up again.

Just say no to… whatever these guys are selling. Photograph of Curtis Candy Company display in Jacksonville, Florida, 1947, courtesy of the State Library and Archives of Florida.

For the most part, I am a fairly practical baker. But the road to sobriety is pocked with potholes of madness. Fruitcake is one of mine.

I have always liked the idea of fruitcake. As with so many once-traditional things, I detest what it has become. And so, for years now, I have made a hobby of redeeming it.

Fruitcake used to be serious business. It has its origins in late-medieval spiced breads, whose spice and sugar alone made them suitable for festivals, and it remained expensive and laborious until the end of the nineteenth century. In Northern Europe and America, oranges, lemons, and citron had to be imported from warmer climes, and white sugar to candy them was pricey. Raisins too had to be imported, and then seeded — one at a time, by hand. Then California farmers developed seedless raisins and Florida farmers turned to citrus; by 1900 raisins were a cheap source of iron to stick in children’s food, and by the 1950s you could stock your freezer with concentrated orange juice. Industrialization made fruitcake ordinary, and dyeing glacéed cherries green and selling bricks by mail order made it a joke.

But the idea remains sound: a sweet, complex, festival cake that is both accessible to home bakers and laborious enough to be special; fruited, spiced, boozy, and completely over the top; powerfully enjoyable but easily shared, because a slice or two is probably all you need. Perfect for Christmas. In theory. How to restore it?

The first step is to candy your own citrus peel and use a mix of dried fruit for color and flavor. No technicolor goo, nothing not identifiable as food. That was easy to figure out but takes a bit of work — but hey, it’s Christmas, right?

The second step was harder to figure out but, as it happened, far easier to implement. How do you make a cake sturdy enough to hold monstrous quantities of fruit and nuts without its turning into a brick? The cake part of fruitcake is essentially a pound cake, and you need lots of eggs, but you also need something I only recognized once I’d started researching historical baking: gluten structure. Many old cakes were beaten hard after the flour, butter, and eggs were combined, and that’s what holds this fruitcake together. The method here is much the one Rose Levy Beranbaum uses in her “Perfect Pound Cake,” though it appeared decades before in a 1950 Betty Crocker cookbook (go figure). It is both an easier and a more reliable way to get all the eggs into the batter without its breaking, and the resulting crumb is about perfect.

Here, then, is real, serious fruitcake. Note that it must rest for two weeks before serving — so get started early!

To have a meal with chopsticks is to engage in the immaterial world of relationships and ideas. People don’t use chopsticks in a restaurant to show their dexterity. Rather, it demonstrates one can navigate different cultural contexts, adapt to various social environments, and demonstrate a level of open mindedness. These are all fine purposes, but they have little to do with the pragmatic task of moving pieces of food from the plate to the mouth. And in many contexts, the temptation is to master chopsticks to fake sophistication. Seth Higgins, “On Lug Wrenches and Chopsticks, in Front Porch Republic

When I worked in an office, back in the early days of this century, I used to walk across the street to the grocery store on my lunch break to make a salad at the salad bar, which I took back to eat at my desk. I have always loved salad bars, maybe because when I was a kid they were the only chance I had to choose whatever I wanted to eat. Choice and abundance! Very American. Anyhow: I enjoyed my salad-bar lunches, but I found them difficult to eat. A fork is lousy at picking up raw carrots, no less so if they are grated — and more so if the fork is one of the plastic ones they give you at the store. Actually forks are pretty lousy at picking up raw vegetables, period. Radish? Cucumber? I felt like I was trying to kill Dracula. Have you ever tried eating raw spinach with a plastic fork? And let’s not even talk about those baby ears of corn.

Then I found, in my desk drawer, an unused pair of takeout chopsticks from a Chinese restaurant. And they worked. They worked really well. They picked up everything, from baby corn to the last little bits of shredded carrot. They worked so well that to this day I eat salad with chopsticks — at home, when nobody is watching — simply because they are more efficient than a fork.

Sometimes, to paraphrase something Freud may or may not ever have said, a pair of chopsticks is just a pair of chopsticks. And pretty much all the time, you’re better off choosing the right tool for the job instead of thinking of tools as symbols.