Long Live the Bunnyman (original) (raw)

Illustration by Brenna Thummler

Two weeks shy of Halloween and just around midnight, the Bunnyman first appeared in a grassy Virginian field on land slated for rebirth as the manicured Kings Park West subdivision. It was 1970, and Air Force Academy cadet Robert Bennett and his young bride-to-be, Dusty, chatted in their car. A shadow emerged from the dark silhouette of the field’s tree line. As the shape neared the car, its vague edges morphed into a white, black and gray furry costume with lengthy bunny ears.

The Bunnyman charged toward Robert and Dusty.

“You’re on private property, and I have your tag number,” he screamed.

He heaved a wooden-handled hatchet at the couple. The axe smashed Robert’s window and landed at the cadet’s feet. The Bunnyman disappeared back into the shadows.

A week later, the Bunnyman reappeared. Paul Philips, a security guard for the construction at Kings Park West, spied the Bunnyman swinging a hatchet at a roof support on a new house. Philips yelled at the Bunnyman to stop, but the Bunnyman turned and screamed at him: “All you people trespass around here. If you don’t get out of here, I’m going to bust you on the head.”

Philips went for his gun in his car, but when he returned, the Bunnyman had vanished into the surrounding trees.

The Washington Post reported the sightings only twice, but news of the Bunnyman swept Fairfax County’s sprouting middle-class neighborhoods like a virus. The Fairfax County Police Department received 50 reported sightings of the Bunnyman within two weeks. Wild, terrible tapestries built partly on fact and partly on myth grew—myths of an irate, uncompromising Bunnyman who disemboweled and strung up kids off Old Colchester Pass; myths of a lunatic asylum escapee who lived within the trees and fed on bunny carcasses. Fairfax families already felt vulnerable at a time when weathered horse ranches, family farmhouses and ripe orchards disappeared, their close-knit communities replaced by suburban tract housing and clipped hedges.

Within days, schoolchildren like 11-year-old Jim Waters were petrified to bike to school.

Waters is now a 56-year-old guitar player and co-composer for the rock opera “Legend of the Bunnyman.” I met him at De Clieu Café in Fairfax on an early spring day in 2015.

“The story went from a guy in a white bunny suit with an axe who vandalized a couple of times to an axe murderer at the end of Guinea Road,” he says. “As an 11-year-old, I couldn’t give it any perspective.”

When Waters first heard about the Bunnyman, the headlines read: MAN IN BUNNYSUIT SOUGHT IN FAIRFAX and two weeks later: THE RABBIT REAPPEARS. By the time Waters was middle-aged, the legend of the Bunnyman was a segment on Fox Family Channel’s “Scariest Places on Earth” entitled TERROR ON BUNNYMAN’S BRIDGE.

Collaging firsthand experiences, local myths and imagination, Waters and fellow guitarist Chris Pillar spent 18 months writing the two-and-a-half-hour rock opera told from the Bunnyman’s perspective. They performed it with their band Mantua Finials through 2013 and 2014.

Waters states in a 2013 article with Bonnie Hobbs of The Connection, “It was odd and creepy—and the incidents were real. … I think someone living near Kings Park West was unhappy that the woods there were being torn down for houses.”

Members of the Rock Opera Band

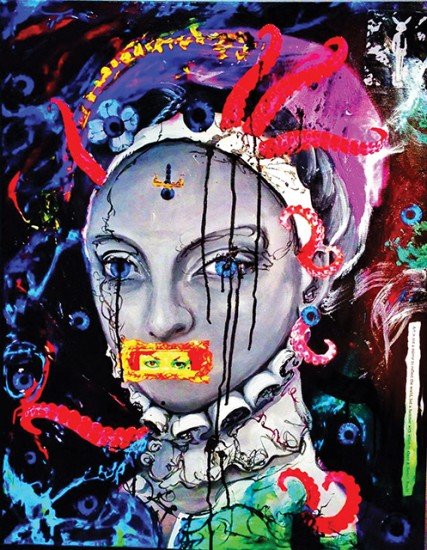

Around the same time I meet Waters, I’m introduced to artist and curator Jessica Kallista, 45, at one of her installations at Epicure Café in Fairfax. Kallista wears red lipstick, and her smile is impish and watchful, like she’s tasting a delicious secret. She creates colorful collages mixing illustrations, photography, paint and poetry.

Over the din of a crowd, I asked her why she displays so many bunnies in her artwork. She tells me she’s fascinated with the dark mixture of Bunnyman stories that stirred up local suburbia from 1970 onward.

After meeting Waters and Kallista, my interest piqued, I discovered the research paper, “The Bunny Man Unmasked,” written by Fairfax County librarian Brian Conley. His years-long research concluded the man in the bunny suit was a local disturbed by the development of the area.

Let’s face it. Old Virginia’s countryside—fruit orchards and lavender fields, horse ranches and wild blackberry bushes—makes us breathe easier. Asphalt paths and overpriced houses within suburbia suffocate our sense of peace. The Bunnyman may not have known how to stop suburban sprawl, but he wasn’t going out without being heard. He may have been the perfect storm of mental instability and exasperation at the unraveling of Virginia’s small-town communities.

Conley, Waters and Kallista sought to understand not just the Bunnyman’s actions but how and why his legend evolved. What does the Bunnyman mean to them? What does a man in a bunny suit mean to any of us? At first judgment, his actions repulse us. Bizarre actions scare regular people. A lone man creeping around at night in a whimsical costume dredges up a dark fog of pop-culture images. Donnie Darko; Stephen King’s IT; Chuckie.

But the Bunnyman also represents something else. The Individual. The Underdog. The Rebel.

“The Bunnyman is an icon for shaking things up, doing things in a different way, not accepting the status quo, of making noise. It’s the underbelly, the weird, urban legend in Fairfax, which on the surface is calm. The Bunnyman torments suburbia,” says Kallista.

Early afternoon on Easter Sunday, I drove to Bunnyman Bridge, on one of the first warm days in 2015. The bridge lies fraught with superstitions and twisted folklore, and I visited it on the brightest and most hopeful of days to hold any boogeymen at bay. The bridge is, in fact, 8 miles from the wild field where the Bunnyman appeared with his hatchet.

Off the busy Fairfax County Parkway, the speed limit dropped along a narrow country road. Two-room paint-chipped houses and old willow trees bordered construction lots. Adjacent land was filled with slow-rolling bulldozers, sawdust, concrete piping and in one lot, what appeared as construction supplies piled up under a Baptist revival tent. A mile down the road, a sign appeared advertising a new Hindu temple. The trees thinned, and the next generation of houses emerged. Four stories high and constructed with gray stone, three-car garages expand over leveled green lawn and patches of daffodils arranged in perfect circles.

I drove over a crossroad, and tall willow and birch trees clustered in groves of wild grass reappeared. A small lane marked Yellow Brick Road disappeared into a mouth of trees. And then, around a corner, a high stone bridge covered in faded yellow paint. Bunnyman Bridge. The signs read: No trespassing. Trespassers will be prosecuted. No parking.

I parked on a swampy section off the tapered road. A dank smell from a small stream clung to the bridge’s mouth. A high wall topped by long rusted metal planks held up a wall of gray stones and the train tracks forty feet overhead. I walked under the bridge opening where disemboweled children were said to hang, and I didn’t dawdle because my imagination is my master and it told me bad spirits followed me into the narrow, wet tunnel. I exhaled as I emerged on the other side into midday light. Two sparrows fluttered in a field. Long brown grass floated like unkempt hair in a fetid creek. It could be 1970. It could be 1870. No car engines, no planes overhead. No people, no squirrels, no chipmunks. No sounds but the stream and the wind. I think of all the horror movies I watched before becoming a mother and how, right now, I am a lone character tempting the devil.

It was time to obey the signs and go home.

Back onto the road, past the McMansions and rundown homes and onto Fairfax County Parkway. I stopped and started at 16-lane intersections. The hues of a springtime blue and the sweeping Virginian sky disappeared. Reappeared. And then gone, behind wires and strip mall signs, traffic lights and $5,000-a-month high-rise condominiums.

Forty-five years after the Bunnyman, a hectic, detached air lays siege over the region. This translates to a satisfactory efficiency for residents on three-year government contracts. But some of us are here to stay.

Since the Bunnyman and small Northern Virginian communities disappeared for good, life is easier than ever around here. Dangling vines, creeping ground ivy and pricker brushes are clear-cut for in-ground sprinklers. Dozing lizards are evicted for strip-malls and sports complexes. Air-conditioned everything distempers Virginia’s tyrannical subtropical heat. Razed, cleaned and sterilized. Scrubbed of all uniqueness, character, legends … except for one. The Bunnyman.

A legend that evolved from a simple story of a disgruntled local uncertain how to reconcile small-town life with unstoppable suburban sprawl. “There was a great community bond when there were less people here. The more people, the more diluted,” says Waters, who moved to the area as a child in 1961.

There is, however, ample opportunity to reconcile the absence of character in Fairfax County. NoVA schools rank high nationally. There are countless choices for extracurricular activities for children and upscale shopping and entertainment for adults, and the employment and affluence to afford the cost of living, which is 238 percent above the national average.

The residents are wealthy and healthy. In 2014, the Northern Virginian Health Foundation concluded Fairfax County is one of the most physically healthy counties in the state.

But there is a price to pay. Suburbia is lonely. Few people have time for community if they want to afford the dream. Suburban sprawl creates crawl-spaces for us to slip unnoticed through life. Protracted mental health problems abound. Thirty percent of Northern Virginians are considered at high-risk for chronic binge-drinking. One in four teenagers suffers from depression, and one in four adults lives with a diagnosable mental illness.

Kallista is one of those adults who lived with diagnosable mental illness. She struggled with agoraphobia and depression for 12 years, cloistered in her home in Kings Park West, the very land the Bunnyman was desperate to save.

“It takes 30 minutes of walking just to get out of the suburb. I had no idea how to find a community or support,” says Kallista.

Kallista told her husband she wanted to leave Fairfax County and move somewhere in the Midwest, perhaps closer to her close-knit hometown of Alton, Illinois, on the Mississippi, or to D.C., somewhere she could build a community of artists.

“Ask yourself what you want and just make it happen here,” he said.

Those words changed her life.

‘Sulca the Young Anarchist’ by Jason Davis, Jessica Kallista and Javier Padilla / Photo courtesy of Jessica Kallista

Four years later, I sit on a crimson couch in Kallista’s studio, Olly Olly. We drink strong coffee in a bright blue room overlooking a busy street in Fairfax Center. It seems the Bunnyman has brought us together.

Kallista explains how she and fellow artists Jason Davis and Javier Padilla founded the Bunnyman Bridge Collective in 2013 and now includes artists Abner De Jesus and Toni Hitchcock. The collective’s name drew on the wild, absurd grittiness of the local legend. The Bunnyman Bridge Collective may be inspired by the Bunnyman’s mission to preserve community, but rather than the Bunnyman’s solitary method of scaring locals, the five artists are moved by a sense of cooperation to build community and connection within the suburbs. Like the Bunnyman, they resist the status quo, but unlike him, they don’t accept suburbia is tantamount to a guaranteed loss of community.

“We are a suburban art movement. We want to establish what people are hungry for,” says Kallista.

The collective knows suburbanites seek a connection with people in the area as an outlet from their work and home lives. “The Bunnyman Bridge Collective counteracts the fragmented relationships between neighbors who know each other only well enough to nod (hello to each other) … We recapture interconnectivity in order to put an end to the isolation and alienation experienced by individuals living in suburbia,” says Kallista.

The Bunnyman Bridge Collective is tireless. Over the past two years, they initiated dozens of events to engage local residents. Free Art Friday is an art-drop in NoVA’s public spaces. Any resident who stumbles upon these Bunnyman Bridge Collective artworks can bring the piece home as its new owner. Hitchcock broadened this idea and now brings Free Art Friday to Culpeper.

Since January 2014, the collective has curated nine exhibits at the Epicure Café and Olly Olly in Fairfax. Themes include topics such as Bodylore, Captive and Pandemic to evoke conversations within the local community. The Bunnyman Bridge Collective exhibits own work and also actively seeks to showcase new artists living and working in NoVA. Local bands, food and drinks bring a party atmosphere to each exhibit, encouraging people to socialize and get to know each other.

Open Art Gym is a weekly event at Olly Olly, each Tuesday evening from 6-9 p.m. The art gym encourages residents who are hidden away in their homes to explore creating new forms of art together. “Olly Olly is a call to everyone in suburbia to come out, support and benefit from an authentic sense of community in order to build a more balanced suburbia,” says Kallista.

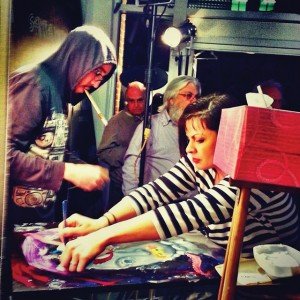

Davis and Kallista collaborating on live painting of ‘Sulca’ / photo couresty of Jessica Kallista

“The Bunnyman is a story that belongs to Northern Virginia. It’s people saying, ‘I remember it this way,’ and another person saying, ‘It happened that way,’ and all the memories get melded together to make a continuing story,” says Kallista. Out of this shared story, the Bunnyman Bridge Collective is inspired to build a new community 45 years after the Bunnyman disappeared back into the woods.

The Bunnyman legend is still discussed on the Internet, school newspapers still write about him, and once in a while the Post and other local papers tie in a human interest story around the Bunnyman. And the local stories are gory. Bodies turned inside out. A man dressed only in rabbit pelts stalking people through the woods. An escaped inmate from the Clifton Asylum murdering locals—the thread of terror still trickles through Northern Virginian’s consciousness.

In the end, the Bunnyman was never caught. The police dropped the case within six months. The Bunnyman was never the child-killer lunatic lurking in the woods. He was a man upset over the loss of his community. But people fear bizarre behavior, we fear what we can’t make sense of, and the myth grew.

The Bunnyman is still alive and well in people’s minds. Reported sightings of him had spread to Maryland by 1973, and this Halloween, you can drive to Old Colchester Bridge to join the other thrill-seekers who want to feel the murderous soul of the Bunnyman chill their hearts. That is, if you can sneak around the Fairfax County Police checkpoints, just for a tantalizing taste of danger in the suburbs.

(October 2015)