An Interview with Conductor James Conlon, Part 1 – Opera Warhorses (original) (raw)

This interview was conducted in Maestro Conlon’s office at the Los Angeles Opera, whose facilitation is gratefully acknowledged:

*****

[_Below: Maestro James Conlon; resized image, based on a photograph, courtesy of the Los Angeles Opera._]

Wm: Many of the American vocal artists I have interviewed did not choose musical careers until well into their college years, but you experienced what might be regarded as an elite musical education – admittance to the New York City’s La Guardia High School of Music and Art, acceptance into the Aspen Music Festival School of Conducting at age 18, then collegiate training at the Juilliard School. How did these experiences during your teenage years lead to your decision to become a conductor of classical music and opera.

JC: First, let me suggest that “elite”, which implies membership in a privileged class, is not the word I would use to describe the education I received. There is nothing elite about me. I don’t come from a musical family.

The La Guardia high school is part of the New York City public school system. Much of my education came from the free access I had to the New York Public Library. There was no means for an elite education. Without the library, I wouldn’t have been able to do anything. Furthermore, the students admitted into the Juilliard School reflect those with musical and artistic talents, regardless of class.

Yet, it was not my schooling at La Guardia and Juilliard that led to my decision to be a conductor. I had that epiphany at 13 years old. I fell in love immediately with classical music and opera. Sometime in October or November of 1963 it was clear to me that I wanted to conduct. Once I knew that, the education followed on that decision. The whole focus changed. I did nothing but study.

Within several months I started piano lessons, I was able to sing in the children’s chorus of an opera company in Queens. I did have the great fortune to grow up in New York City, with its strong commitment to public education. I entered Juilliard as a conducting student already knowing that I wanted to conduct, and to experience what was to be the beginning of The Lincoln Center years.

There is no school of conducting as there is for piano. Every conductor’s education is different from that of others. There are certain centers now with some great conducting teachers, such as those begun by Jorma Panula in Finland, a country that succeeds in educating its whole population. Any place with massive investment in education will prove to be an advantage to those who are extremely talented.

Conductor Gustavo Dudamel is a leader in the fight to save music education in the schools. I strongly believe in such efforts.

Wm: While on a Juilliard tour of Europe at age 20, you secured an invitation to work as a musical assistant at the following year’s Spoleto Festival, during which time you conducted a performance of Mussorgsky’s “Boris Godunov”. The idea of an American 21 year old conducting an opera during a European international festival seems quite extraordinary. Could you elaborate on how this came to be?

JC: I was in Spoleto because I was assisting the Juilliard school orchestra which was on tour. I was invited back for an assistant conducting job, coaching singers and was thoroughly involved in the musical preparation. Spoleto provided me with the opportunity to conduct one performance.

This was one of the first productions of the real Mussorgsky “Boris”. Although the Shostakovich version had started to be played, in 1971 it was still Rimsky-Korsakov’s reorchestration of the work that ruled the world. I knew the opera well in Rimsky’s version.

[_Below: a scene at the 2008 Spoleto Festival; resized image, based on a photograph from wikipedia.org._]

That “Boris” was the beginning of my professional life. I am extremely grateful and loyal to Spoleto, that beautiful, medieval town that has not changed in 40 years.

Wm The first time I had ever seen you conduct was in your late 20s when you conducted a San Francisco Symphony concert at the Concord (California) Pavilion with Montserrat Caballe as the guest artist. But by that time you had already made your conducting debuts at the New York Philharmonic, the Metropolitan Opera and the Scottish Opera. It’s known that soprano Maria Callas had spoken on your behalf. What other mentors do you credit with helping you achieve such milestones at such an early age?

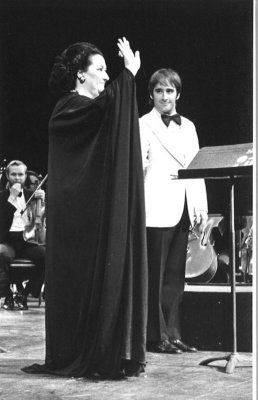

[ _Below: Soprano Montserrat Caballe (foreground) appears with the 28 year old conductor James Conlon at the Concord Pavilion; resized image, based on a Nancy L. Burnett photograph._]

JC: I can’t exaggerate how extremely fortunate I am to have been working at a young enough age to touch the end of that generation. You’ve heard how Maria Callas impacted my career. She was at Juilliard teaching her master class, and happened to see me conducting a rehearsal of Puccini’s “La Boheme”. Conductor Thomas Schippers had been scheduled to perform but became ill. When Callas heard about this, she told the Juilliard musical administration “replace Schippers with that one, he’s going to have a great future.” So I was not only the beneficiary of the master classes, her personal input led to a breakthrough assignment.

Then my career got going. I was able to collaborate with basso Boris Christoff and his brother-in-law, baritone Tito Gobbi. Mrs Christoff died last summer at the age of 90, so all of their clan is now gone. I also learned from basso Italo Tajo and tenor Carlo Bergonzi, among others.

Then, in the mid-1970s, I was “adopted” by the Italian conductor Dick Marzollo, who had been Toscanini’s assistant, and who had worked directly with the Italian composers Pietro Mascagni, Ruggero Leoncavallo and Riccardo Zandonai. He had prepared many of the great singers of the day for their roles. His father was a Venetian, who had lived in Britain and wanted to give his son an English name. For some reason, decided on the name “Dick”.

Marzollo was orphaned very young. He was a rigid personality. For someone teaching, such a structured approach to remembering past events is of great advantage. Since Marzollo had rigidly learned his craft, he could identify how the ethic has changed – vocally and aesthetically. I now realize how much of the culture of Italian opera performance styles that still existed in the 1970s has been lost. He was primarily a pianist. He did not have a good career as a conductor. I sought out his knowledge. Marzollo lived to 1991, so I had 17 years to pick his brain.

I also came to know the great verismo soprano Magda Olivero, who is now 101 years old. She sang the title role in Puccini’s “Tosca” on a tour for which I conducted. She is an extraordinarily fantastic musician.

[Below: Soprano Magda Olivero; resized historical photograph, from the lastverista.wordpress.com.]

I visited her last year while I was conducting “Rigoletto” at La Scala. Even though I hadn’t seen her for many years, she remembered me and invited my wife and me to her home, where we spent three hours and learned all sort of things. She remembered Marzollo, called him fantastico and was thrilled to reminisce.

I have had a lot of luck. My fortune in knowing these great Italian artists of the previous generation has molded my sense of their viewpoint, that the increasing uniformity of style is washing out cultural characteristics.

This is a phenomenon that has reached all levels of Italian society. There were 2000 dialects of Italian spoken at the end of World War II. Those dialects are disappearing. The fact is that children do not respond to their parents in the regional dialect, they speak the standard Italian. There is a language and technique of bel canto, a term that embodies more than vocal writing of the early 19th century Italian masters. How few people today are able to sing that way. What was considered basic to conductors, is now becoming a rarity as well. There are those who continue to insist on observing the traditional methods of preparing singers and conductors, but much has been lost.

It pains me any time a significant part of the repertory falls away, as many of the Italian verismo works have done in recent years. As we accumulate a greater volume of works, some of this process of crowding out older repertory is inevitable, but dropping works of great merit from the performance repertory is deplorable.

Wm: One of your impressive career moves was assuming the musical directorship of the opera and symphony companies in Cologne, Germany in your late 30s. One imagines that those years in that beautiful, historic city on the Rhine with its great cathedral and the Hohenzollern Bridge spanning the river that is the location of Wagner’s “Ring”, would have inspired a deeper understanding of German culture and especially of Wagner’s music dramas. What are your thoughts about how the Cologne experience may have shaped your later career?

JC: To wake up every day to see the Rhine was a wonderful experience. I grew up in New York City, where we also have an inspiring river. I love both the Hudson and the Rhine. However, whenever I have the opportunity to interact with German musicians, it is an extraordinary experience.

I will tell you that I have never sought a music directorship job. The then intendant wanted me to come as principal conductor. I was at Rotterdam, which was my first orchestra. I thought about the Cologne job. I would not be that far away from Rotterdam, and because it’s close by, it might be interesting and I would have opportunities to learn a great deal. But what sold the job was that I could be a music director in an opera house.

I had been a guest conductor at the Metropolitan Opera since 1976. I spent hours watching James Levine preparing the music, and rehearsing the orchestra. In Cologne I would have a place to try to do what Levine does.

[_Below: the Cologne Cathedral and the Hohenzollern Bridge spanning the River Rhein; edited image, based on a photograph from photos4travel.com._]

In any house there is a lot of “music director’s repertory”. As a young conductor, you will not have all of the opportunities you would like to have to conduct. I was 36. At that point, I had an impressive CV, that listed a lot of major opera companies where I had performed. But I was frustrated by the fact that I had not one opportunity to conduct a Wagner opera or any of the three Mozart operas with Da Ponte libretti (“Don Giovanni”, “Cosi fan Tutte” and “Marriage of Figaro”).

I loved them from having grown up at the Met in those great years. I saw Christa Ludwig, Walter Berry, Karl Boehm, George London, Birgit Nilsson. I said to the intendant that if I came to Cologne, I would want to conduct Wagner.

In Cologne I did all ten major Wagner operas and half of them again in Paris. I have done that since 1990. You can only do that if you are the music director. Before I took that position in Cologne, I had never had done a Richard Strauss opera. I wanted to do Debussy’s “Pelleas et Melisande” and Berg’s “Wozzeck”. That was what the Cologne job meant to me.

I am repertory driven. None of my jobs have ever been because they were “right” for my career. I work in direct relationship to the music. I went to that opera house because they would let me be the music director. One still can make guest appearances elsewhere. I’m going to Rome because Riccardo Muti asked me to do it.

Symphony is a different situation from opera.I have had two symphonic music directorships, in Rotterdam and Cologne. You have more opportunities to do what you want to do as a guest symphony conductor than as a guest opera conductor.

For the continuation of the interview, see: An Interview with Conductor James Conlon, Part 2.