Parenting styles: An evidence-based, cross-cultural guide (original) (raw)

Researchers have been studying parenting styles for more than 50 years, and you’ve probably heard some of their claims:

- The authoritarian parenting style is strict and dictatorial, and associated with children who may struggle more with self-regulation and socioemotional functioning.

- Permissive parenting is more affectionate and child-centered, but because caregivers don’t enforce limits, their children can be at higher risk for developing behavior problems and unhealthy habits.

- Authoritative parenting is warm and nurturing, but also mindful of setting age-appropriate limits. Caregivers try to guide behavior through reasoning, rather than punishments, and they make kids feel acknowledged or included during family decision-making. This style is consistently linked with positive child outcomes.

- Uninvolved (or “neglectful”) parenting is lacking in both affection and limits. The children of uninvolved parents have the worst outcomes of all.

Now, notice the careful wording: We’re talking about links and associations, not definitive proof that a specific parenting style causes or contributes to child outcomes.

Nevertheless, it seems pretty clear which style parents should strive for, which is why you’ll see organizations like the American Academy of Pediatrics remind medical professionals that authoritative parenting “has been strongly associated with positive mental health and behavioral outcomes in children and adolescents.”

Moreover, when child development experts speak approvingly of approaches that go by other names (like “supportive parenting,” “positive parenting,” “Montessori parenting,” “gentle parenting,” “attachment parenting,” or “dolphin parenting”), it’s usually because they judge these approaches to be variants or subtypes of authoritative parenting.

But is it really this cut-and-dried? No!

In the real world, people don’t sort neatly and precisely into these categories. You or someone you know might straddle the line between two styles, or switch styles across the day, depending on the circumstances. When a young child takes a dash into traffic, even a very permissive parent may start acting authoritarian.

Moreover, some people favor an approach that doesn’t match up with any of styles mentioned above. There are cultures where authoritative parenting – as defined by Western psychologists – is largely absent, and it’s not clear that folks meet the criteria for permissive or authoritarian parenting either.

Finally, we have to acknowledge that the causation is complex. Parenting styles help shape the way kids turn out. But there are other factors, too, and parenting itself is influenced by children’s behavior.

None of this means we can’t learn from the research on parenting styles, or that many kids wouldn’t benefit from an authoritative approach. On the contrary, I think the original ideas proposed by Diana Baumrind – the psychologist who coined the term “parenting style” – are amazingly relevant for 21st century families. So in the rest of this article, I will provide you with an overview of these ideas, and the big questions they invite us to ask:

- How do the parenting styles differ on a philosophical level, and what specific behaviors do researchers use to classify a caregiver’s style?

- Are the resulting classifications accurate or reliable?

- Why is it wrong to assume that parenting styles are stable, clear-cut, or the same in all cultures?

- What do we know about child outcomes? And how do other factors – besides parenting style – shape the way our children turn out?

What do researchers mean when they talk about “parenting style”?

Parents influence their children through specific practices, like engaging babies in language-learning opportunities, encouraging kids to play outdoors, and troubleshooting sleep problems.

But parenting – so the argument goes – is more than a set of specific practices. What about the overall approach to guiding, controlling, and socializing kids? The attitudes that parents have about discipline, nurturing, and the emotional climate this creates?

It’s this general pattern–this emotional climate–that researchers refer to as “parenting style” (Darling and Steinberg 1993).

So how do psychologists distinguish one parenting style from another?

The philosophical underpinnings of parenting styles: It’s about attitudes toward authority

It started in the 1960s with the developmental psychologist, Diana Baumrind. Observing trends in the United States, Baumrind noticed that very idea of “authority” had fallen into disrepute.

Thoughtful people had rejected the dictatorial, authoritarian mindsets of the past. But they hadn’t stopped there.

In addition to opposing the kind of authority that reigns by fear and force, folks had seemingly rejected what the philosopher Erich Fromm called rational authority — the authority that we grant to people who have special areas of competence. People like like teachers and scientists. Therapists and surgeons. Plumbers and pilots.

It’s the kind of authority that helps, rather than exploits – a limited authority based in equality and cooperation, not mindless submission. We trust rational authorities to make judgments on our behalf, not because we shut off our brains, but because we are reasoning beings. If their judgments don’t make sense to us, we ask for clarification, and they explain.

When Baumrind looked around, she saw lots of parents who weren’t embracing rational authority. Instead, many parents fell into one of two camps.

1. The strict, authoritarian, obey-me-without-question types. These were the parents who held their children to an inflexible standard of conduct (often derived from religious beliefs), and who favored harsh measures (including hostile remarks, threats, shaming, and severe punishment) to ensure compliance. They expected children to obey without question – without any “verbal give and take.” It was the parent’s job to restrict a child’s autonomy, and keep the child in his or her “place” (Baumrind 1966).

2. The permissive, child-centered, never-impose-boundaries types. Reacting against the whole notion of authority, these parents allowed their kids to determine their own behavior as much as possible. Their goal wasn’t to teach, nor serve as role models. Instead, their purpose was to be accepting of children’s impulses and actions, wherever they might lead. They didn’t encourage children to meet any external standards of conduct. They put very few demands on children, and avoided any sort of parental control (Baumrind 1966).

To Baumrind, this was a contrast between extremes. Wasn’t there a compromise? A moderate strategy that fosters self-discipline, responsibility, and independence?

The answer, according to Baumrind, was to exercise rational authority. Compared to their children, parents possess special knowledge about what’s required to get along in society. They can therefore provide the guidance of rational authority – using reasoning, positive reinforcement, and the age-appropriate application of standards — to help kids learn how to balance their freedoms and responsibilities.

Some folks were doing just this, an approach she dubbed “authoritative.” And so Baumrind identified a total of three distinct parenting styles:

- Authoritarian parenting, which emphasizes blind obedience, highly restricted autonomy, and the control of children through threats, punishments, shaming, hostile remarks, and the withdrawal of affection.

- Permissive parenting, which is characterized by warmth, responsiveness, and the fostering of self-determination, but which fails to hold children accountable to limits or rules.

- Authoritative parenting, a more balanced approach in which parents expect kids to meet certain behavioral standards, but also show high levels of affection, recognize children’s feelings and needs for autonomy, and encourage kids to think for themselves. The use of reasoning is emphasized over other forms of control. Physical punishment, shaming, and other harsh tactics are avoided.

Later, researchers added a fourth style, uninvolved or neglectful parenting, in which parents offer little or no warmth, and fail to enforce limits (Maccoby and Martin 1983).

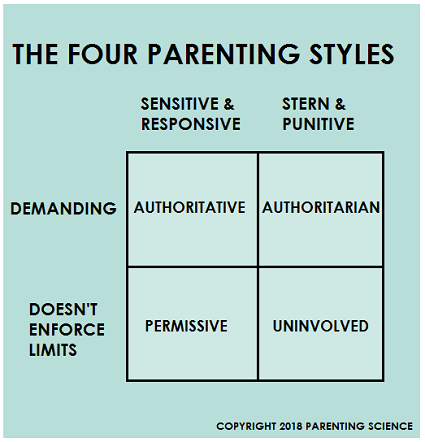

In addition, researchers re-formulated the original definitions by rating each parenting style according to two dimensions – “responsiveness” and “demandingness”:

- Responsiveness is “the extent to which parents intentionally foster individuality, self-regulation, and self-assertion by being attuned, supportive, and acquiescent to children’s special needs and demands” (Baumrind 1991). This dimension has also been called “support,” and it includes behavior that communicates warmth and caring.

- Demandingness refers to “the claims parents make on children to become integrated into the family whole, by their maturity demands, supervision, disciplinary efforts and willingness to confront the child who disobeys” (Baumrind 1991).

This allows the four parenting styles to be represented by a 2×2 matrix (below).

At a glance, the 2×2 matrix reveals why so many people regard authoritative parenting as optimal.

Being responsive and sensitive is a good thing, and two styles – authoritative and permissive – meet this criterion.

Being demanding is also helpful for aspects of child development, and two styles – authoritative and authoritarian – display this feature.

But only one parenting style – authoritative – ticks the boxes for both dimensions.

Now, heads-up for those of you interested in cultural differences, especially with regard to autonomy:

I’ve said being responsive is a good thing, and that’s well-supported when it’s defined in terms of acknowledging children’s perspectives, desires, and emotions, and making them feel loved, accepted, and cared for. For example, cross-cultural research suggests that this kind of responsiveness reduces a child’s risk of depression and social withdrawal (Rothenberg et al 2020).

But if we look at the way responsiveness is being defined above, it may also entail the promotion of the culture-specific value of individualism – a stance that emphasizes the separation of the self from others, and prioritizes autonomous decision-making.

As we’ll see below, there are societies where successful adjustment depends instead on fostering interdependence, where people view the self as intimately connected to the needs and interests of other people, and individuals are supposed to prioritize group interests and social harmony over autonomous decision-making. In such cultural settings, the pro-individualistic aspects of authoritative parenting may not necessarily lead to better child outcomes.

Digging deeper: How, specifically, can we identify an individual’s parenting style?

It’s easy to say that authoritative parents are both responsive and demanding. Or that authoritarian parents are insufficiently responsive. Or that permissive parents aren’t demanding enough.

But what is “insufficient”? What is “enough?” Who decides this stuff, and how does it get measured?

These are important questions, because we can’t apply research to our everyday lives if we don’t know how our own parenting behavior would be categorized. So let’s take a quick peak behind the researcher’s curtain. If you were participating in a study, how would the study’s authors determine your parenting style?

Sometimes, researchers make direct observations of parenting behavior

This is the “let’s collect genuine behavioral data” approach, and it often looks like this: Put families in challenging situations, and then see how parents behave.

It’s an excellent way to see what parents actually do (as opposed to relying on their self-reports). It gives you something concrete to measure, and, when done right, it can reveal meaningful differences in the way that parents attempt to influence or control their kids.

For example, researchers might ask a parent to sit alone with her toddler while the child works on a puzzle. The family interactions are recorded, and researchers look to see how the parent responds. Does she encourage the child to think of his or her own solutions, and provide positive emotional feedback to keep the child engaged? Or does the parent get bossy, telling the child what to do, and criticizing his or her mistakes?

A more common approach is to ask people to fill out questionnaires

Strictly speaking, this approach isn’t measuring parenting behavior so much as it’s measuring what people decide to report about parenting behavior_._ But it’s quicker and cheaper than setting up behavioral observations, so it gets used a lot.

For families with young children, researchers usually give the questionnaires to parents, so we’re finding out what parents believe (or are willing to report) about themselves. In families with older children, researchers sometimes ask the kids to do the reporting, in which case the children indicate their pwn perceptions of how their parents behave.

What do these “parenting style” questionnaires look like?

There are several in use. Typically, they consist of statements about parenting behavior, and respondents rate how often the parent exhibits that behavior (on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1= never and 5 = always).

For example, there is the Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PDSQ), which asks parents to rate statements addressing different aspects of authoritative, permissive, and authoritarianparenting (Robinson et al 1995). Here’s a sampling of items from the PDSQ.

Statements about responsiveness and democratic participation (associated with authoritative and permissive parenting):

- “I give comfort and understanding when my child is upset.”

- “I take my child’s preferences into account when making family plans.”

Statements representing a failure to impose limits (associated with permissive parenting):

- “I give into my child when he / she causes a commotion about something.”

- “I ignore my child’s misbehavior.”

Statements measuring reasoning (associated primarily with authoritative parenting):

- “I give my child reasons why rules should be obeyed.”

- “I help my child understand the impact of behavior by encouraging my child to talk about the consequents of his/her own actions.”

Statements measuring hostility and raw power assertion (associated with authoritarian parenting):

- “I yell when I disapprove of my child’s behavior”

- “When my child asks me why he/she has to do something, I tell him/her it is because I said so, I am your parent, or because that is what I want.”

I could give you more examples, but I hope you get the idea. You rate each item, researchers compare your scores against whatever cut-offs they have established, and voilà!Your parenting style has been classified, rather in the manner of a “Which Disney Princess Are You?” online quiz.

How accurate or reliable is the questionnaire-based approach to identifying people’s parenting styles?

As noted above, we’re not measuring parenting behavior directly. What people say they do might deviate from what they actually do. So this is a source of error or murkiness. And there are other issues too.

For instance, how people interpret the statements matters. Suppose I asked you to rate this item from the PDSQ (Robinson et al 1995):

“I set strict, well-established rules for my child.”

Researchers might use this to determine if you are permissive, but how did you interpret the statement?

Maybe when you read it, you thought of a parent who is busy regulating all aspects of a child’s life. You envisioned a parent being overly restrictive or intrusive. You don’t identify with that, so you give the statement a low rating, indicating that you never do this, or do it only sometimes.

Alternatively, you might have read that statement and decided it meant something like “in the areas that that matter to me, I make it clear to my child that certain behavior is not acceptable.” So you give the statement a high rating, stating that you do this “always” or “often.”

What happens when researchers collect these answers from people? We might get parents sorted in misleading ways, with some individuals categorized as either permissive or authoritative, not because they treat their children differently, but because they interpret the meaning of the statements differently.

So when we hear researchers claim that they’ve demonstrated a link between a parenting style and a particular child outcome, we shouldn’t take the claim at face value. We need to know more about the way researchers measured parenting. As I note in another article, I think this can partly explain conflicting findings about the permissive parenting style.

The methodological concerns aside, do people sort themselves neatly into different parenting style categories?

Not necessarily. No.

As you can imagine, some parents filling out these questionnaires may come up with a mix of answers. Researchers might end up labeling them with a single parenting style, but it’s a loose fit.

Then there is the problem of culture. Baumrind’s original scheme was inspired, in part, by differences she had observed among a specific population – predominantly white, mostly middle class, 20th century Americans. As I’ll note below, her categories don’t always map onto the types of parenting that people practice in other cultures.

Finally, some critics reject the idea that parenting styles are stable — remaining the same regardless of the circumstances. For instance, you might act like an authoritarian parent when there is a conflict about safety, but act like authoritative parent when you are trying to encourage your child to learn certain social skills, like empathy.

Also, as Judith Rich Harris noted (1988), the same parents might use different styles with different kids. For example, when dealing with children who are self-regulated and cooperative, parents may find it easy to be authoritative. But when they clash with kids who are disruptive and defiant, parents may react with more authoritarian tactics. As we’ll see below, children’s behavior can influence the way parents behave.

What can we conclude from the research on child outcomes?

From the beginning, researchers anticipated that authoritative parenting would be linked with the best child outcomes. It was more or less built into the definition of this parenting style, because the officially-recognized components of authoritativeness were already believed to facilitate socioemotional functioning, resilience, resourcefulness, and self-regulation. All good things, right?

Similarly, permissive and authoritative parenting were defined in ways that would make us expect certain downsides.

Yet no matter how intuitive something appears to be, proving causation can be tricky.

Ideally, we’d want to perform controlled experiments: Randomly assign some children to receive different types of parenting, keep everything else in their lives as similar as possible, and then compare outcomes. But ethical and practical considerations rule this out, so we’re left with other types of evidence.

One source of information comes from cross-sectional studies — “snapshots” of a particular point in time.

Researchers select a group of families, and measure each child’s current status, along with the type of parenting he or she has been receiving. Are there any correlations? These studies can’t provide us definitive evidence that parenting styles affect children’s outcomes. But researchers try to filter out the effects of other variables (like socioeconomic status) using statistical methods.

Researchers can also hone in on causation by tracking children’s development, and looking for evidence of change.

For instance, if kids tend to become more anti-social over the years — even after controlling for their initial behavior problems (and other factors) — that’s stronger evidence that a parenting style is at least partly responsible.

What, then, have we learned about parenting styles from these studies?

You can read the details by following the links below, but the highlights are these:

Kids from authoritative families tend to be well-behaved, and successful at school. They tend to be emotionally healthy, resourceful, and socially-adept.

Kids from authoritarian families are at somewhat higher risk for “externalizing symptoms” – such as aggression and defiance. In addition, these kids may develop less social competence, and – in many societies – they are more likely to suffer from “internalizing symptoms” (such as anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem).

Children with permissive parents receive high levels of warmth, which is beneficial for a child’s emotional health. However, children from permissive families may be at an elevated risk for externalizing behavior problems, and they also seem to fare worse when it comes to risky, health-related behaviors – like substance use, excessive screen time, and poor sleep.

Kids from uninvolved families are the worst off in all respects. Most juvenile offenders have uninvolved parents (Steinberg 2001).

What about the role of culture?

Are the four basic parenting styles universal?

Strictly speaking, no. Not if we are looking for all aspects of the definitions to align with what folks are doing in different cultures.

Baumrind’s ideas have been successfully applied in places as varied as Brazil, China, Scandinavia, Mediterranean Europe, and Turkey (Martinez et al 2007; Zhange et al 2017; Turkel and Teser 2009; Olivari et al 2015). But not everything matches up.

For example, in a study of Korean-American parenting, researchers found that over 75% of the sample population didn’t fit into any of the standard parenting style categories (Kim and Rohner 2002). And Ruth Chao has argued that the authoritarian parenting style—as defined by Western psychologists—doesn’t have an exact counterpart in traditional Chinese child-rearing (Chao 1994).

Moreover, when Su Yeong Kim and her colleagues analyzed parenting among Chinese Americans, they found that the most prevalent style (which they called “supportive”) was similar to authoritative parenting in every respect but one: These parents attempt to influence behavior by shaming, a tactic of psychological control that Western psychologists associate with authoritarianism (Kim et al 2013; Kim 2013).

The mapping may even more difficult when we try to apply Baumrind’s parenting style categories to populations with radically different lifeways.

For example, considered what’s normal among the world’s last hunter-gatherer societies.

First, there’s the generous freedom to explore, even under conditions that your local child protective services would deem neglectful: If a baby picks up a dangerous tool, nobody rushes in to take it away (Hewlett and Roulette 2016; Marlowe 2010).

Then there’s what Western parenting style experts would deem a lack of disciplinary guidance or “follow through”: When little kids engage in physical aggression, parents either ignore it, laugh it off, or move the children away from whomever they are trying to attack (e.g., Howell 2010; Marlowe 2010; Konner 2010; Endicott 2013).

Parents reject punishment, especially physical punishment, so this certainly doesn’t look like authoritarian parenting. But it doesn’t really look like authoritative parenting, either – not according to the standard definition. What’s conspicuously absent is instructive feedback or pushback. People don’t tell young children their behavior was unacceptable, in part because they believe young children “lack the wits” (Marlowe 2010).

So this must be permissive parenting, right? Except that hunter-gatherers also provide guidance, and kids learn about limits.

Caregivers actively train young children to meet the social standards that are crucial for success in foraging societies. In particular, they play games with babies that teach them to interact appropriately, overcome selfish impulses, and share.

Moreover, as kids get older, they are increasingly held to account – by parents and others in the community.

For instance, adults might not interfere when an angry child tries to hit people with a stick. But if that child hits another, older kid, he might get smacked back (e.g., Marlowe 2010, p. 197).

And people of all ages employ mechanisms of psychological control — teasing, ridiculing, or shaming kids when they behave in ways that seem selfish or anti-social. Parents may also try to shape behavior with scare tactics — stories about supernatural creatures who punish bad conduct (Lew-Levy et al 2017). These are responses that the “Which Disney Princess Are You?” type questionnaires tend to count as authoritarian.

So where does normal hunter-gatherer parenting fit into Baumrind’s scheme of parenting styles?

Arguably, it doesn’t fit anywhere, and if you tried to force one of the standard labels, people would get the wrong impression.

What about situations where we can confirm that the same parenting style exists in two different cultures? Are child outcomes the same in both settings?

Not always, no.

For example, as we’ve already noted, high levels of psychological control are identified with authoritarianism, and they have been linked with elevated rates of internalizing problems in children. But the effect size varies.

In a study of parenting in 12 different cultures, the connection between psychological control and internalizing symptoms was weaker “in cultures where more psychological control by parents is more normative” (Lansford et al 2018). In other words, if your parents are very controlling — but their behavior is similar to most other parents in your community – you won’t suffer as much emotionally.

Then there is the question of autonomy and freedom of choice — giving kids latitude to make their own, independent decisions.

This is sometimes considered a crucial aspect of authoritative parenting, and it has been associated with better child outcomes in societies that are democratic and individualistic.

But what if you are growing up in a culture that favors interdependence over individualism? And what if your society is also hierarchical, and reverential toward the wisdom of elders?

In such cultural settings, children may expect their older, wiser parents to make decisions for them. It’s a sign that their parents are living up to their responsibilities, and showing that they care. For these kids, the “free choice” aspect of authoritative parenting may not be as beneficial (Marybell-Pierre et al 2019).

So culture can modify the links between parenting style and child outcomes. Yet there is still a widespread tendency for authoritative parenting to “edge out” other styles — especially in societies where children need formal schooling to succeed in life.

In an international meta-analysis of 428 published studies, researchers found that authoritative parenting is associated with at least one positive outcome in every region of the world. By contrast, authoritarian parenting is associated with at least one negative child outcome (Pinquart and Kauser 2018).

Why is authoritative parenting so often linked with better outcomes?

Maybe it’s because the components of authoritative parenting (showing warmth, setting limits, using reasoning, and allowing for autonomy) help kids develop into socially responsible, self-regulated, well-adjusted people.

And maybe it depends on the kinds of behavior that get rewarded outside the home – e.g., in the classroom, the neighborhood, the workplace. For instance, when schools are run along authoritative principles, kids from authoritative families may have an easier time understanding and meeting their teacher’s expectations (Pellerin 2004).

What if two parents disagree, and adopt different parenting styles?

Some people wonder if kids require consistency across caregivers, so much so that they would be better off if everyone used the same approach — even if that means doubling down on authoritarianism or permissiveness.

In other words, if your co-parent insists on being permissive (or authoritarian), should you conform? Or is it better steer your own course as an authoritative parent?

I’ve found three studies that have addressed this question. All three focused on the adjustment of American adolescents, and all three reported the same results: Teens were generally better off having at least one authoritative parent – even if the other parent was permissive or authoritarian (Fletcher et al 1999; Simons and Conger 2007; McKinney and Renk 2008).

So how much does parenting style influence children’s outcomes? What about other factors — like peers? What about the child’s temperament or personality?

Parenting style is important, but it’s just one influence among many. Differences in parenting style – by themselves – explain only part of the variation between kids.

As for the rest, children’s outcomes are also shaped by many other aspects of their environment, including socioeconomic status, culture, schooling, the popular media, and peers.

For example, a study tracking the behavior of Swedish adolescents found that authoritative parenting was linked with less frequent use of alcohol. But for this particular outcome, kids were primarily influenced by peers, their previous involvement in delinquent behavior, and the availability of alcohol (Berge et al 2016).

It’s also clear that genetics, prenatal conditions, and temperament play a major role in child development. In fact, children’s pre-existing behavioral tendencies can influence a parent’s caregiving style.

For instance, consider a child with a difficult, excitable temperament. He’s impulsive, and prone to temper tantrums when something frustrates him. It’s the way his brain is wired up – the result of developmental processes that began before he was born.

This child’s parents start out with the intention to practice authoritative parenting. But, as the years go by, they find it increasingly difficult. His behavior stresses them out, and soon they drift towards other responses. They might become more punitive and authoritarian. Or, alternatively, they might feel helpless, and give up on enforcing limits.

Either way, the child’s temperament has influenced the way the parents behave. They intended to practice authoritative parenting, but their child’s temperament nudged them off course.

Does this really happen? A number of studies support the idea.

For example, consider a study tracking more than 400 children from the age of 3. If children showed early signs of ADHD, their parents tended to become more authoritarian over time (Allman et al 2022).

Or take a study that followed the development of approximately 500 adolescent girls over the course of a year (Huh et al 2006).

At the beginning of the study, the researchers measured the girls’ externalizing behavior problems (e.g., picking fights and engaging in acts of defiance). They also asked girls about the way their parents attempted to monitor them and enforce rules. At the end of the study, researchers repeated their measurements.

The results? Initially low levels of parental control didn’t have a significant effect on a girl’s subsequent development of externalizing behavior problems. But initially high levels of misconduct were a significant predictor of decreasing parental control over time (Huh et al 2006).

In other words, parents were more likely to give up — stop trying to control their kids — if children were more aggressive or difficult to begin with. In effect, misbehavior prompted parents to become more permissive.

Now, none of this means that parents with difficult kids should respond by becoming more authoritarian or more permissive. On the contrary, these responses tend to make things worse.

It’s a pattern reported by a number of studies: When kids struggle with behavior problems, they are more likely to improve over time when their parents adopt authoritative practices (like positive parenting, emotion coaching, and inductive discipline).

But it isn’t easy. We need to acknowledge that some kids are intrinsically more challenging to handle. Their behavior can nudge parents to react in ways that are counter-productive.

Therapists and counselors can help, but they need to address the behavior of both parents and kids (Huh et al 2006). And parents need advice tailored to their children’s temperaments and psychological profiles.

For more information, see my article about parenting stress, as well as my evidence-based tips for handling disruptive behavior problems.

More reading about parenting styles

Interested in authoritative caregiving? I offer more insights and advice in these articles:

- The authoritative parenting style: An evidence-based guide

- Positive parenting tips:Getting better results with humor, empathy, and diplomacy

- Emotion coaching: Helping kids cope with negative feelings

- Inductive discipline: Why it pays to explain the reasons for rules

- Aggressive behavior problems: 12 evidence-based tips

- Teaching self-control: Evidence-based tips

In addition, you can learn more about authoritarian parenting from these Parenting Science articles:

- Authoritarian parenting style: What does it look like?

- Authoritarian parenting: What happens to the kids?

Here are my articles about permissive parenting:

- Permissive parenting: An evidence-based guide

- The permissive parenting style: Does it ever benefit kids?

And check out these, related Parenting Science offerings:

- The health benefits of sensitive, responsive parenting

- Student-teacher relationships: Why emotional support matters

- Oxytocin affects social bonds — can we influence oxytocin in children?

- Teaching empathy: Tips for fostering empathic awareness in children

- The science of attachment parenting

References: Parenting styles

Baumrind D. 1966. Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Development, 37(4), 887-907.

Baumrind D. 1991. The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. Journal of Early Adolescence 11(1): 56-95.

Berge J, Sundell K, Öjehagen A, Håkansson A. 2016. Role of parenting styles in adolescent substance use: results from a Swedish longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open. 6(1):e008979

Calafat A, García F, Juan M, Becoña E, Fernández-Hermida JR. 2014. Which parenting style is more protective against adolescent substance use? Evidence within the European context. Drug Alcohol Depend. 138:185-92.

Chao R. 1994. Beyond parental control; authoritarian parenting style: Understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Development 45: 1111-1119.

Chen X, Dong Q, Zhou H. 1997. Authoritative and Authoritarian Parenting Practices and Social and School Performance in Chinese Children. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 21(4): 855-873.

Darling N and Steinberg L. 1993. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin 113(3): 487-496.Garcia F and Gracia E. 2009. Is always authoritative the optimum parenting style? Evidence from Spanish families. Adolescence 44(173): 101-131.

Endicott K. 2013. “Peaceful foragers: The significance of the Batek and Moriori for the question of innate human violence.” In D. Fry (ed): War, Peace, and Human Nature. Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 241-61.

Fletcher AC, Steinberg L, and Sellars EB. 199. Adolescents’ well-being as a function of perceived interparental consistency. Journal of Marriage and the Family 61(3): 599-610.

Harris JR. 1998. The nurture assumption: Why children turn out the way they do. Free Press.

Hewlett BS and Roulette CJ. 2016. Teaching in hunter-gatherer infancy. R Soc Open Sci. 3(1):150403..

Howell N. 2010. Life histories of the Dobe !Kung. University of California Press.

Huh D, Tristan J, Wade E and Stice E. 2006. Does Problem Behavior Elicit Poor Parenting?: A Prospective Study of Adolescent Girls. Journal of Adolescent Research 21(2): 185-204.

Kim K and Rohner RP. 2002. Parental Warmth, Control, and Involvement in Schooling: Predicting academic achievement among Korean American adolescents. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 33(2): 127-140.

Kim SY, Wang Y, Orozco-Lapray D, Shen Y, Murtuza M. 2013. Does “Tiger Parenting” Exist? Parenting Profiles of Chinese Americans and Adolescent Developmental Outcomes. Asian Am J Psychol. 4(1):7-18.

Kim SY. 2013. Defining Tiger Parenting in Chinese Americans. Hum Dev. 56(4):217-222.

Konner M. 2011. The evolution of childhood. Belknap Press.

Lansford JE, Godwin J, Al-Hassan SM, Bacchini D, Bornstein MH, Chang L, Chen BB, Deater-Deckard K, Di Giunta L, Dodge KA, Malone PS, Oburu P, Pastorelli C, Skinner AT, Sorbring E, Steinberg L, Tapanya S, Alampay LP, Uribe Tirado LM, Zelli A. 2018. Longitudinal associations between parenting and youth adjustment in twelve cultural groups: Cultural normativeness of parenting as a moderator. Dev Psychol. 54(2):362-377.

Lew-Levy. 2017. How Do Hunter-Gatherer Children Learn Social and Gender Norms? A Meta-Ethnographic Review. Cross-Cultural Research 52(2): 213-255.

Maccoby EE and Martin JA. 1983. Socialization in the context of the family: Parent–child interaction. In P. H. Mussen (ed) and E. M. Hetherington (vol. ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, personality, and social development (4th ed., pp. 1-101). New York: Wiley.

Marlowe FW. 2010. The Hadza hunter-gatherers of Tanzania. University of California Press.

McKinney C and Renk K. 2008. Differential parenting between mothers and fathers. implications for late adolescents. Journal of Family Issues. 29(6):806–827.

Martínez I, García JF, and Yubero S. 2007. Parenting styles and adolescents’ self-esteem in Brazil. Psychol Rep. 2007 Jun;100(3 Pt 1):731-45.

Pinquart M and Kauser R. 2018. Do the Associations of Parenting Styles With Behavior Problems and Academic Achievement Vary by Culture? Results From a Meta-Analysis. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 24(1): 75-100.

Pinquart M. 2017. Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with internalizing symptoms in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis Marriage and Family Review 53: 613-640.

Robinson C, Mandleco B, Olsen, SF, and Hart CH. 1995. Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices: Development of a new measure. Psychological Reports 77: 819–830.

Rothenberg WA, Lansford JE, Al-Hassan SM, Bacchini D, Bornstein MH, Chang L, Deater-Deckard K, Di Giunta L, Dodge KA, Malone PS, Oburu P, Pastorelli C, Skinner AT, Sorbring E, Steinberg L, Tapanya S, Maria Uribe Tirado L, Yotanyamaneewong S, Peña Alampay L. 2020. Examining effects of parent warmth and control on internalizing behavior clusters from age 8 to 12 in 12 cultural groups in nine countries. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 61(4):436-446.

Simons LG and Conger RD. 2007. Linking mother-father differences in parenting to a typology of family parenting styles and adolescent outcomes. Journal of Family Issues. 28:212–241.

Smetana JG. 2017. Current research on parenting styles, dimensions, and beliefs. Curr Opin Psychol. 15:19-25.

Steinberg L. 2001. We know some things: Parent-adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of research on adolescence 11(1): 1-19.

Türkel YD and Tezer E. 2008. Parenting styles and learned resourcefulness of Turkish adolescents. Adolescence. 43(169):143-52.

Content last modified 4/2024. Portions of the text are derived from earlier version of this article, written by the same author

Graphic of matrix depicting parenting styles copyright 2018 Gwen Dewar and Parenting Science

Image of mother pressing forehead against child by jacobblund / istock

image of hunter-gatherer rock art photographed by Dietmar Rauscher / shutterstock