Why Do Certain Retail Stores Cluster Together? (original) (raw)

I spend much of my free time digging for old records. Philadelphia, my home, has a rich history of soul music and its countless thrift stores and flea markets offer a fiend like me plenty of opportunity. There are times however, when I prefer the efficiency of shopping at a record store, and although there are record stores in Philly, there is no better cluster of record stores anywhere on the planet than in the Lower East Side of New York City. As it turns out - this pattern can be explained by two extremely important planning-related theories, Hotelling's Law and Central Place Theory.

Stores like Good Records and A1 Records are approximately 2.5 hours from Philly via a combination of bus, subway and walking - but on occasion I will make the journey because the selection at these stores is nothing short of extraordinary. But why do they insist on locating so close to each other? Wouldn't it be more advantageous for these stores to locate farther apart so that they can each enjoy their own dedicated market area?

Think for a moment about the kinds of retail stores that tent to cluster together. Several come to mind: cell phone stores, car dealerships and big box stores are a few. One of the predominant ideas about Central Place Theory is that there is a hierarchy of goods - an order, where higher ordered goods are those that are purchased infrequently like cars and lower ordered goods are those purchased more regularly like milk and eggs.

People are willing to travel farther from their homes to purchase a car than to purchase their breakfast, so it makes sense for rival car dealerships to locate next to each other to take advantage of potential customers who come great distances to shop.

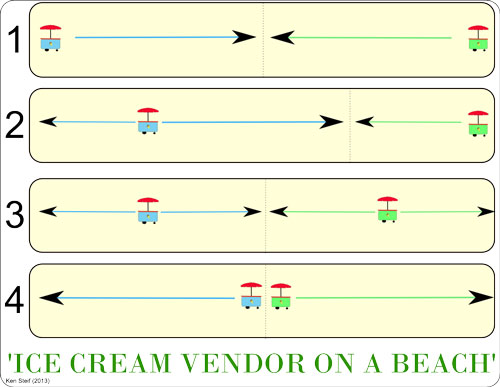

One of the demonstrations I particularly enjoy showing my students is the "Ice Cream Vendor on a Beach" example. On a hot day when most beachgoers avoid getting back in their car to go for a snack, beachfront ice cream is considered a higher ordered good. Panel 1 of the image below shows two ice cream vendors who, to start, have an equal share of the beach market. In Panel 2 however, the blue vendor, exercising her capitalistic right to command a greater share of the marketplace, decides to shift farther down the beach, capturing more customers than her green competitor.

Of course, not be outdone, the green cart shifts toward the center as well, and now, in Panel 3, both cars once again, have equal market share. If the blue cart feels so inclined, she will shift again, and her green rival will follow suit, until both carts are directly next to each other, each with an equal share of the market. The only question for beachgoers then, is whether they prefer Ben & Jerry's or Haagen Dazs.

This basic idea was first described by an economist named Harold Hotelling in an academic paper entitled "Stability in Competition" from 1929. An even broader justification of these patterns was published not long after, in 1933, by a German geographer named Walter Christaller. Christaller's Central Place Theory posited that the size and location of cities was a function of the type of goods they offered and the relative distance consumers would be willing to travel to consume these goods.

The bigger the city, the more higher ordered goods are offered. This is why if you live in a small town, you can probably drive down the road to buy milk, but if you want to buy a diamond ring, you'll travel to a larger city.

I've always been interested in these patterns and I recently sat down with some business location data provided by ESRI's Business Analyst tool in order to discover if there is a relationship between the spatial pattern of businesses and higher ordered goods. I was also curious to test whether certain competitors like Home Depot and Lowe's co-locate like the ice cream vendors in order to share a traveling customer base.

The above image is a three dimensional Kernel Density map showing the relative prevalence of businesses in New York, New Jersey & Connecticut. This map was created from more than 1.23 million business listings in the tristate area. Each listing includes a NAICS Code which indicates the sector or type of business conducted at each location. The first step was to split the data by NAICS code. The image below shows the locations of several sectors used in the analysis.

As expected, Bars & Nightclubs cluster in high population areas while restaurants are located in almost every town throughout the study area. I created 18 of these retail segments and devised an index describing how close a given business type is to its nearest neighbor of the same type and how prevalent that business type is throughout the Tristate area. Formally the index is calculated as:

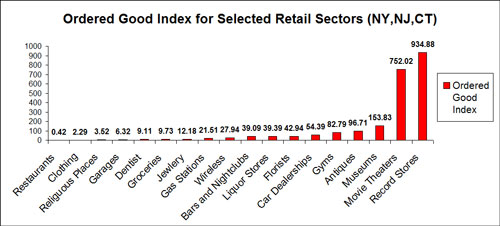

The chart below shows the outcome of the analysis for the 18 sectors. It should come as no surprise that restaurants and clothing stores have the lowest index values - people in rural areas shouldn't have to drive far to eat or buy a new pair of jeans. Because the data included entries for religious institutions, I couldn't help but calculate an index value for Churches, Synagogues and the like. Turns out that God is a lower ordered good - you don't have to travel far to visit him.

Higher ordered goods, according to the index, include record stores, movie theaters, museums, antique stores, gyms and car dealerships. These are examples of businesses which typically cluster together and locate in centralized areas in an attempt to share the market.

What about competition among specific competing firms? It seems like every time I'm near a Home Depot, there's a Lowe's next door; and for every Walmart I pass, there's a Target not far down the road. I decided to pull out the locations for 14 different firms that I suspect may have reason to cluster near one another. I constructed a 'hypothesis test' which asks: Are, for instance, Home Depot locations closer to Lowe's locations than what would otherwise be expected due to random chance alone?

I'll explain how this is done - but if reading about statistical tests bores you - feel free to skip to the next paragraph. First, the average distance is measured between each Home Depot and its nearest Lowe's neighbor. Second, we randomly re-label each point as either "Home Depot" or "Lowe's" and again, measure the average distance between nearest neighbors. This random relabeling procedure is done many times over to create a sampling distribution of distances. If the actual distance between Home Depot and its nearest Lowe's neighbor is less than 95% of the random distances, we can say that these stores are more clustered than what would be expected due to random chance alone.

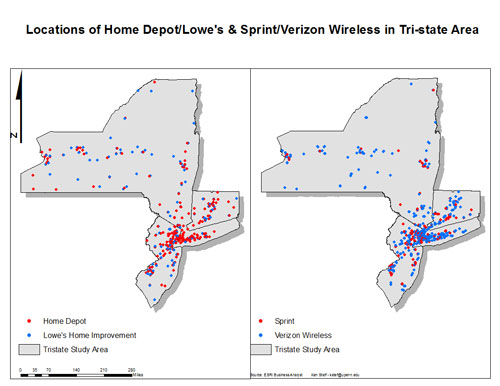

The image above shows locations of both Home Depot's and Lowe's as well as Sprint and Verizon Wireless stores. Both competitor pairs appear, at least visually to cluster near one another, but at this scale, the clustering might just be the result of these firms locating in urban areas. In actuality, the results of the statistical test indicate that Sprint and Verizon are not significantly more clustered than what would be expected due to random chance. Here are the results for all firms chosen for the analysis:

Of all the competitor pairs, just three exhibit statistically significant clustering. Target & Walmart; Starbucks and Dunkin' Donuts; McDonalds & Burger King all exhibit very strong tendencies to co-locate.

These results are surprising. I had mentioned that the Central Place Theory teaches us that people are willing to travel farther to consume higher ordered goods, which is why firms that sell these goods co-locate. While one could make the argument that Walmart and Target, as places for one stop shopping, are in effect, higher order goods, the same argument could not be made for fast food and coffee shops. Maybe coffee shops cluster together for the same reason as ice cream vendors on a beach. Perhaps, in order to avoid leaving the commercial district (or beach), coffee shops locate in close proximity in order to compete over more of the local market share.

Finally, consider the fact that businesses put a great deal of thought into where they choose to locate. They consider the local customer base, transportation options, and yes, the locations of their competitors. Many of these firms are making a very conscious decision to locate near their competitors.

Most interesting to me is that many of the patterns discussed in this article demonstrate just how complex the city system really is. Our towns and cities are comprised of firms and households who each act to maximize their own welfare while being limited by their own irrational assumptions and imperfect information about the world around them. Through it all an extraordinary structure emerges, and by analyzing these patterns we can make more efficient and productive decisions about how to increase the economic vitality of our towns and cities.

In closing, the cluster of record stores in the Lower East Side did not locate there by chance. Their 'agglomeration' makes doing business more efficient. They can share both inputs (lots of used records in New York) and customers. It is also probably the only place on the East Coast where one can find a mint condition copy of Barbara Howard's "I Don't Want Your Love". Of course, this assumes you're willing to spend more than $300 on a record (I'll stick to the dusty crates of my local flea market).

Ken Steif is a Doctoral Candidate in the Graduate Group of the City & Regional Planning Program at the University of Pennsylvania. You can follow him on Twitter @KenSteif