Greece Press, Media, TV, Radio, Newspapers (original) (raw)

Photo by: Stefanos Kyriazis

Basic Data

| Official Country Name: | Hellenic Republic |

|---|---|

| Region (Map name): | Europe |

| Population: | 10,623,835 |

| Language(s): | Greek (official), English, French |

| Literacy rate: | 95.0% |

| Area: | 131,940 sq km |

| GDP: | 112,646 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 32 |

| Total Circulation: | 681,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 78 |

| Number of Nondaily Newspapers: | 14 |

| Total Circulation: | 441,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 50 |

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 277 (Euro millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 17.10 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 36 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 2,540,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 239.1 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 190,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 17.9 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 118 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 5,020,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 472.5 |

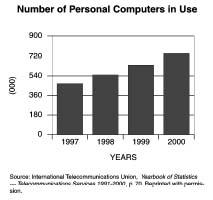

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 750,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 70.6 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 1,000,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 94.1 |

Background & General Characteristics

The Hellenic Republic of Greece has a very active and vocal press greater in the number of newspapers, magazines, radio stations, and television channels than the population of less than 11 million warrants. The high number of publications is a Greek expression of freedom of the press to compensate for decades of suppression by military governments or foreign interventionists in modern Greek history, when the nation alternated between being a kingdom or a republic.

Ancient Greece represents the birthplace of democracy in the history of western civilization. Ancient Greek democracy was not extended to all city-state residents, and the Greek peninsula was a collection of city-states in competition with each other. Conflict among the Greeks led to their conquest by Philip of Macedon and the Greek incorporation into the successive empires of Alexander the Great, Rome, Byzantium, and the Ottomans. Modern Greece did not emerge until 1821, when the wars of Greek independence were waged against the Turkish rulers of the Ottoman Empire. Europe's major powers initially did not want an independent Greece, fearing a disintegrating Ottoman state would leave the eastern Mediterranean open to either Egyptian or Russian expansionism. Expatriate newspapers published in Greek in Vienna kept the Greek language and culture alive and encouraged rebellion. European public opinion, influenced by British poet Lord Byron and the romanticism of the principles of democracy in Ancient Greece, sided with the Greeks, and Great Britain was forced to accept the role of protector of the Greek people. Frequent disagreements among Greek political factions and the failure to create a unified state led Europe's three major powers, Great Britain, France, and Russia, to impose a monarchy upon the Greeks, with a foreign prince as king and neutral arbitrator to bring about national consensus. Foreign interventionism, military takeovers, and feuding Greek politicians have clouded Greek politics for almost two hundred years and forced the Greek media to struggle underground, face outright suppression of its publications, or suffer regulation by the central government censor in Athens.

The reign of King Otto, a Bavarian prince selected for the Greek people by European powers in 1832, witnessed considerable centralization of authority in the capital of Athens. The Kingdom of Greece isolated and ignored Greece's indigenous political traditions, created new hierarchies of power staffed by Germans loyal to King Otto, and failed to revive agriculture and the economy. The Greek people did not always fight back with print media. They gravitated toward oral debates, republicanism, and armed insurrection. What print media existed within Greece was considered either biased or anti-royalist. King Otto's first period of governance ended with a military coup in 1844, an internal Greek interventionist theme that would regularly be a part of Greek politics until 1975. Greece's second attempt at democracy relied more upon political patronage rather than one man, one vote democracy. Bribery, corruption, and appeals to Greek nationalism to achieve a "Greater Greece" by freeing Greeks still under Ottoman rule led to British and French intervention in Greek politics once again, and a refusal by the major powers to allow the further breakup of the Ottoman Empire. Greek nationalism was thwarted, but the desire to bring all Greeks under one national flag would add a new theme to Greek politics and newspapers. The military intervened again in 1862; King Otto returned permanently to Germany.

A new monarchy was created in 1864, once again by Europe's major powers, who extended an invitation to Danish prince William to come to Athens and become King of the Hellenes (king of the Greek people). Prince William adopted the reigning name of George I, and a new constitution was written with power invested in the Greek people, a single-legislative chamber, and a monarch with specific but substantial powers. Political personalities and political clubs came to characterize Greece in the late nineteenth century. Greeks regularly expressed their views in oral debates and in print—their positions frequently in opposition to government policies. Both political clubs and artisan guilds brought out the voters and imposed their views upon the nation. From 1865 to 1875, Greece witnessed a succession of seven general elections and 18 different administrations. Greek politician Kharilaos Trikoupis wrote a newspaper article about the political gridlock within Greece's national governments and criticized the king for supporting governments representing minority political groups rather than the larger parties, which dominated the Greek Parliament. Trikoupis was arrested for treason for his comments, but he was later released and went on to serve as Greece's prime minister. The political pressure applied to the monarchy by the print media led to political reform. After 1874 Greek prime ministers were usually selected from the strongest party represented in Parliament.

The reign of King George I ended by assassination in 1913 by a deranged Greek in the newly freed Greek district of Salonika. Greek media kept the public emotionally charged over the issues of a "Greater Greece," the acquisition of the island of Crete, and economic collapse. The Greek media traditionally served as spokesmen for Greek politicians and political parties, and were usually divided between the supporters of the monarchy and media supporters advocating a republic. World War I and King Constantine's attempt to keep Greece neutral led to political rivalry between the palace and Eleutherios Venizelos, one of Greece's most influential politicians of the twentieth century. The dispute over national policy led Venizelos to claim that King Constantine was pro-German and disrespected the wishes of the Greek people to join the Allies against the Central Powers. The strategic importance of Greece in the Allied fight against the Central Powers nations of the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria led to French interventionism in Greek politics and the disposition and exile of the king in 1917. The Venizelos press implied that King Constantine denied Greece the opportunity to expand its boundaries as a member of the Allies in the war against Germany. The monarchy remained under a figurehead king, Alexander I, a son of King Constantine. Royalists and republicans expressed their opposition to each other and polarized the Greek state. An unsuccessful attempt on the life of Venizelos and the unexpected death of the young King Alexander led to the restoration of King Constantine. The Greek nation remained evenly split between republicans and royalists. The side in power suppressed the voice of the other side. King Constantine was exiled a second time in 1922 after disastrous defeats by the Greek army at the hands of the Turks that the Venizelos press blamed on the Greek king and princes who commanded the nation's armed forces. King George II lasted less than a year on the throne and was exiled in 1923. Venizelos returned from exile to govern the Greek republic. He remained in power until the worldwide economic depression reached Greece. Venizelos' failure to revive the Greek economy led to his overthrow by the military in 1935.

The monarchy was restored in the person of King George II. The instability of Greek politics forced King George to turn to the military to govern what seemed an ungovernable state. General Ioannis Metaxas restored public order, but the cost was high. Greece became a one-party state, repressed human rights, suppressed the media, and contributed to further divisions within the Greek body politic. The secret police brutally suppressed all dissent. Political dissent led to arrest, prison, or exile. Torture was regularly used to extract confessions. The regular conflict between royalists and republicans, and the brutality of the Metaxas dictatorship led to opposition support forming around a Greek Communist Party engineered from Moscow. Germany and Italy invaded in 1941. The end of World War II and the retreat of German armies left Greece in a state of civil war between the Communists and elements of the royalist government-in-exile in London. Both Great Britain and the United States, fearful of a Communist Greece strategically located in the eastern Mediterranean threatening the Suez Canal, supported the restoration of the monarchy to counter Moscow's influence.

The defeat of the Communists in the Greek Civil War did not lead to a national healing. Royalist and republican rivalries resurfaced in the Greek press and within Greek political parties. The reign of Paul I (1947-1964) witnessed an attempt to bring economic stability to Greece with the imposition of prime ministers and political parties that were pro-Western and more rightist in political affiliation. Greek newspapers urged greater freedom of expression, which the military and the central government in Athens were not always willing to tolerate. Greece's only radio and television stations were government owned and expressed the opinions of the party in power.

Greece's last king, Constantine II, began his reign in 1964 with the nation expecting Greece to become a true constitutional monarchy, with the king and the military outside of politics. Political rivalries between Greek politicians and personalities, Konstantinos Karamanlis of the National Radical Union Party and Georgios Papandreou of the Center Union Party, during the decades of the fifties and sixties further destabilized Greek politics, placed the neutrality of the monarchy at risk, and generated fear within the Greek military that leftists allied to the Soviet Union would make Greece a Communist ally. In 1967 Greece's limited democracy was overthrown in a military coup. The regime ruled by propaganda and terror. Political parties were dissolved, the media was suppressed, closed down, or censored, and human rights were curtailed. King Constantine II attempted a countercoup to restore democracy but failed and fled into permanent exile. The monarchy remained in name until it was abolished by the military in 1973. The military regime used public interest in television for its own political and ideological interests. The views expressed in the media were "government-controlled overt propaganda." During seven years of military rule, television stressed consumerism over politics. The military junta's 1974 attempt to annex the eastern Mediterranean island of Cyprus with its large Turkish Muslim population led to a war with Turkey and the collapse of the military regime. The monarchy was rejected by a national referendum in 1974, and Greece officially became a republic.

The creation of the Hellenic Republic and the adoption of a new Constitution in 1975, amended in 1986, did not immediately remove antiquated press laws dating back to the Metaxas era of the 1930s. The Constitution of 1975 created Greece as a parliamentary democracy with a president as head of state and a prime minister exercising executive authority. The prime minister is the leader of the largest party in the Greek Parliament. A cabinet is appointed with the approval of the Greek president on the recommendation of the prime minister. The president of the Hellenic Republic is voted into office by Parliament for a five-year term. The Greek Parliament ( Vouli ton Ellinon ) is a one-chamber legislative body with 300 members. The judges for the Supreme Judicial Court and

the Special Supreme Tribunal are appointed for life by the president after consultation with a judicial council.

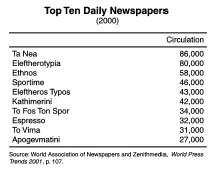

The return of democracy brought a proliferation of Greek newspapers. The largest circulation dailies are in the capital of Athens. Ta Nea is Athens' largest daily newspaper with 168,800 readers (all circulations as of 1995) followed by Eleftheros Typos with 130,000 readers. Other leading Athenian daily papers include Eleftherotypia 114,000 readers, Ethnos , 66,100 readers, Apoyevmatini with 61,500 readers, and Adesmeftos Typos, 60,000 readers. Additional Athenian daily newspapers include Athens News (4,500), Avghi (2,500), Avriani (15,700), Eleftheri Ora (2,300), Eleftheros (9,800), Estia (3,900), Express (25,000), Imerisia (10,000), Kerdos (23,000), and Nafteboriki (35,000), financial dailies, and Kathimerini (35,500), Niki (11,800), and Rizospastis (16,400). The two largest newspapers in Thessaloniki are the dailies Makedonia , 17,000 readers, and Thessaloniki , 14,000 readers. New entries into the journalism field include O Pothos , a gay newspaper, and Patras Today , a daily electronic newspaper and magazine in Patras. Circulation among daily newspapers has steadily declined. Sunday newspapers have increased circulation from 857,000 papers in 1993 to 920,000 in 1998. However, 30 percent of all printed newspapers in Greece remain un-sold. To compensate for lost revenues, newspapers court advertising. Automobiles, banks and other financial institutions, computers and cellular phones, and the public sector are the four primary types of advertising found in the print media. Advertising for cigarettes, educational institutions, and travel are alternative sources for print revenue.

Greek newspapers are less political then they once were. However, some of the major dailies were still clearly identified in 1991 as supporters of a particular political party or ideology. The Akropolis , circulation 50,800, is an independent center-right publication. Eleftheros Typos, circulation 135,500, is a more conservative right-wing independently owned publication. Avgi , with 55,000 readers, is regarded as the official mouthpiece of the Greek Left Party, and the 40,000 circulation Rizopastis is the print voice for the Communist Party of Greece. Avriani , 51,000 readers, is a center-left publication, as are the independent Eleftherotypia with 108,000 subscribers and Ta Nea , circulation 133,000. The independent Ethnos with circulation of 150,000 is regarded as a more left-wing paper than is Avriani , Ta Nea , or Eleftherotypia . A still influential politically oriented newspaper in spite of a circulation decline is the center-right publication Kathimerini .

A wide variety of periodicals are published in Athens. General interest magazines are Economicos , Ependytis, EpohiExormissiExperimentParonPontiki , Prin , Status , and To Vima . Special interest periodicals include the women's magazine Agonas Tis Gynaekas , the English language Athenian , the political publication Anti , maritime periodical Efoplistis , economics magazine Epiloghi , and the business journal Kefalaio . The magazines Balkan News , ChristianikiGreek NewsNea Ecologia, and Politika Themata are all Athens-based publications. Papaki is a relatively new magazine created by journalism students of the Department of Communication and Media at the University of Athens.

Two percent of Greek newspapers and magazines are exported to Cyprus, the United States, Germany, and Great Britain. German and British print publications are the largest in number imported into Greece. Demand in Greece for foreign publications corresponds to the number of tourists in Greece on holiday. There are 600 newsagents and 500 subagencies in the Greek provinces for the distribution of printed media. Within Greece there are 12,000 places where the print media is sold. The number of agents, agencies, and distribution centers exceeds the demand and the general population's needs in comparison to the other nations in the European Union.

Greek radio stations ERA-1 and ERA-2 are the official government radio broadcasting stations. Athena 98.4 is a municipal radio station broadcast from Athens. There are 1200 privately owned radio stations in Greece. Top commercial radio stations, all Athens-based, are Antenna 97.1, Aristerea 90.2, Flash 96.1, Radio Athena 99.1, and Sky 100.4. Privately owned Greek radio stations include 100 FM Melodia, a Greek station based in Athens, 101.9 FM-Studio 19, 102.4 FM, 88.8 FM-STAR FM Corfu,

which offers the top 10, dance, and the top 30 in Greek music, 9.59 FM-Fly, 9.61-Flash, a station broadcasting news and talk shows, 94.5 FM Radio Thessaloniki, and Radio ONE FM. The Greek government operates three television stations, ET-1, ET-2, and ET-3. The most popular commercial television stations, all broadcast from Athens, are Antenna-TV, Aristera TV, Kanali 5, Mega Channel, and SKY TV.

Economic Framework

Greece is a mixed capitalist economy with the public sector accounting for almost half of the gross national product (GNP). Tourism is a key industry. Foreign exchange earnings bring needed revenue. Greek membership in the European Union has benefited Greece. The economy continues to improve as economic reforms take root. National deficits have been reduced, monetary policies tightened, and inflation rates are falling. High unemployment is still a problem, and many unprofitable state enterprises await privatization. The Greek labor force is divided among industry (21 percent), agriculture (20 percent), and services (59 percent). The nation's primary industries, in addition to tourism, are food and tobacco processing, textiles, chemicals, metal products, mining, and petroleum. Historically an unstable Greek economy was the result of political unrest among the nation's political parties, rivalry between royalists and republicans, foreign interventions, wars, and military coups. In the late twentieth century, Greek political life began to mature, become less volatile, and be stabilized by membership within the European Union.

Throughout most of modern Greek history, each political party has had its own newspaper with the party leader serving as editor. Only recently have political party newspapers separated themselves from the party. During the dictatorship of the "colonels" from 1967 to 1974, many newspapers were closed, censorship prevailed, and surveillance of reporters and editors was widespread. After 1974 the media in Greece has been transformed. Advertising plays a decisive role in media revenues and a partisan press has declined, while market-oriented newspapers dominate. Entrepreneurs and ship owners are the new media barons with a few publishers dominating all media. Newspapers are currently less an extension of political parties than a business enterprise. Greece's most profitable printing and publishing empires, based on sales and profits, are the Lambrakis Press, Tegopoulos Publications, Pigasos Printing and Publishing, Press Foundation, Limberis Publications, Apogevmatini Publications, and Kathimerini Publications.

Since deregulation of the media in the 1980s, Greece has grown in television and radio stations. Each station offers more advertising, imports programming from other countries, and broadcasts more political debates. With admission into the European Union, the Greek media is required to conform to the regulations established by the Directive Television Without Frontiers . The Greek media is debating policy issues about the amount of broadcast time allocated to advertising, program quotas, protecting minors, and the private ownership of multiple forms of the media by one person or organization.

The largest daily newspapers based on circulation remain the 17 newspapers published in Athens. There are 280 local, regional, national, daily, and Sunday newspapers published in Greece. The Sunday press is exclusively published in Athens. However, readership continues to decline. To increase readership, the Greek press has resorted to redesigning the newspapers' names and layout, publishing new papers, and offering giveaways such as free trips, houses, and consumer goods. Greece publishes more than 500 popular and special interest magazines. Most magazines are published monthly. Thirty are consumer magazines. The highest circulation magazines are television based and affiliated with game shows. An increase in specialized magazines is designed to attract younger readers in fields such as music, computers, sports, business, finance, car and motorcycles, technology, history, home furnishings, and interior design. And, yet, celebrity gossip and television magazines still have the highest circulations.

Press Laws & CENSORSHIP

The Greek press is regarded as highly politicized and to gain readership is given to sensational news stories. Even though the restoration of Greek rights was guaranteed by the Constitution of 1975, the Greek government has been slow to give up monopolistic control over some media forms. The Constitution of 1975 specifically prohibits censorship in any form, and any government practice hindering freedom of the press is strictly forbidden. However, press restrictions in some form dating back to the Metaxas era of the 1930s remained in effect until August 1994.

The media played an important role in 1989 in the collapse of Prime Minister Andreas Papandreou's government, when the press revealed that media liberalization allowed Papandreou to use the power of the prime minister's office and political patronage to affect what was printed. Greek governments now have an official government spokesman to respond to the media's criticisms, a position similar to that of the presidential spokesmen in the United States. The prime minister's cabinet has a Minister of Press and the Mass Media. This office played a crucial role in both bringing the 2004 Olympic games to Greece and is coordinating the international communications that will be required for the games. There are no restrictions placed on foreign journalists or foreign media operating in Greece.

In 1987 the state monopoly of radio and television ended, but until 1989 government radio and television stations continued to serve as powerful propaganda tools for the political party in power. A lawsuit brought by Athens mayor Militiadis Evert challenged the use of government stations to support candidates and was accepted for hearing by the Greek courts. In April 1989 it was ruled that the state monopoly of broadcasting violated the European Council standards. The Greek Parliament legalized the private ownership of radio and television stations in October 1989. Like the press, privatization of broadcasting led to a proliferation of new radio and television stations. The media is now a frequent critic of the Greek government's forcing the state to improve its image. Although the state-sponsored Elliniki Radiofonia Tileorasi (ERT) is still the dominant force in radio and television broadcasting, an independent committee was created in 1989 to administer ERT, improve its programming, and to weaken cabinet control of ERT.

Since the deregulation of television, most Greek households watch private television. Variety shows dominate private television broadcasting. Private television stations repeat successful formats such as soap operas. If a show lacks sufficient popularity after two years, it is cancelled. With more television channels, more Greeks are watching television. The most watched television shows are news programs, films, and series. The greatest criticism of private television broadcasting is that the shows broadcast are characterized as "glorified tabloid newspapers."

With deregulation the popularity of the state television channels has drastically declined, and each government channel has accumulated a substantial debt. To

attract more viewers, government television (ERT 1, ERT 2, and ERT 3) is providing more entertainment features, cultural programming, environmental series, and animal interest programming. Greek series starring major Greek actors are now broadcast on government channels. ERT 3's focus is on regional programming and culture. By investing in digital television, ERT plans to regain a larger share of the viewing audience.

The National Broadcasting Council (NBC), created in 1989, oversees radio and television broadcasting and remains the buffer between the government and the broadcasters. NBC oversees advertising practices, journalistic ethics, and programming. NBC has levied fines against stations for showing "reality" shows and for inaccuracies in news programming. Some stations were fined for failure to pay copyright fees associated with the right to broadcast a series. The National Broadcasting Council is turning its attention to radio and television stations still failing to obtain a broadcast license.

News Agencies

Five news agencies serve Greece: Athens News Agency (ANA), Macedonian News Agency, Athens Photo News, LocalNet News Agency, and ONA, Omogeneia News Agency. Media associations in Greece include Journalists Union of Athens Daily Newspapers (ESHEA), Foreign Press Association (FPA), Panhellenic Federation of Editor Unions (POSEY), Journalists' Union of Macedonia and Thrace Daily Newspapers, Balkan Press Center, and the Union of Editors of Periodical Press. Greece has two news "infobanks", InNews and the National Communications Network.

Broadcast Media

Greek radio began broadcasting in the 1930s during the Metaxas dictatorship. Television broadcasting began during the "colonels" dictatorship in the 1960s. Both radio and television were extensions of the state and served as propaganda instruments for the military. After 1974 Greek political parties accused the party holding the prime minister's office of using the broadcast stations for their own benefit. A state monopoly of the broadcast media continued after 1974. The Constitution of 1975 gave radio and television to the state to directly control. The state controlled the limited air frequencies and radio and television stations providing only government views and policies. Change came when the other major political party won control of Parliament. The cabinet minister in charge of the media was the nation's chief censor. Deregulation of Greek media came from outside the country when Greece applied for membership in the European Union.

In 1986 the newly elected mayors of Athens, Piraeus, and Thessaloniki were members of the opposition party. Each mayor launched new radio and television stations. Each was taken to court and won. Law 1730, approved in 1987, stated that local radio stations could belong to municipalities or local authorities or companies in which the shareholders were Greek citizens. In 1988 the mayor of Thessaloniki transmitted television programming from foreign satellite channels on UHF frequencies. The mayors of Piraeus and Athens followed suit. During the trial the Greek government realized that media reform was needed. In June 1989 a parliamentary committee was established to determine whether or not television stations in Greece should be private. Large Greek investors wanted the privatization of the broadcast media. Law 1860, approved in 1989, permitted the operation of non-state television channels and created the National Broadcast Council (NBC) to supervise the industry. Mega Channel, owned by the Teletypos publishing group, and Antenna TV, owned by a Greek ship owner, were quickly set up. Both television stations are the nation's most popular. Because there is so much unregulated broadcasting in Greece, the Greek government in July 1993 announced rules for broadcast media licensing. A change of Greek governments in October 1993 gave television licenses to Sky TV and 902 TV, whose license requests were previously denied.

The government Ministry for Press and the Media was not created until July 1994. Law 2328, approved in 1995, regulates the electronic market and determines the legal status of private television and radio stations. Only the Communist Party objected to the 1995 law. The Ministry of Press and the Media determines prerequisites for the granting and renewal of licenses to private television stations, determines programs appropriate for children, and the proper use of the Greek language in broadcasting. Licenses for radio stations must also meet the Ministry's criteria, which determines advertising parameters, and regulates the framework for private media research companies. Although the government has more strictly forced the broadcast media to obtain licenses, many are still in violation. In 1997 and 1998, 19 local stations (6 in Athens and 13 in Thessaloniki) were shut down for nonpayment of copyright fees. Over 1,200 radio stations broadcast throughout Greece. Each of Greece's 52 administrative regions has 2 or 3 local commercial stations. Many are unlicensed. The Greek government permits 3 types of radio stations to broadcast: state-owned, municipal, and private. Most Greek radio stations offer news and current events, music, Greek music, easy listening music, sports, rock music, and nostalgia music. Only one station plays classical music. News and easy listening music stations have the largest listening audiences.

With the deregulation of television, Greece went from 3 state television stations to 140 national and local stations. Mega Channel and Antenna TV control the largest share of the audience market with over 60 percent of the viewers and 65 percent of the advertising revenues. State television has a viewing audience of 8 percent and advertising revenue earned of 7 percent. Both Mega Channel and Antenna TV's popularity is based on sitcoms, satire shows, game shows, soap operas, movies, and made-for-television movies. Fewer educational and documentary programs are aired. FilmNet, the first pay-television channel, began broadcasting in 1994, showing major movies and sporting events. Super Sport and Kids TV are two additional pay-television channels that are widely popular in Greece. Cable television is currently under development. The government television channels and Antenna TV use satellites to show Greek programs to Greeks residing elsewhere. CNN, Euronews, MTV, and TV 5 are stations broadcast via satellite into Greece.

The Ministry of Press and Mass Media along with the Ministry of Transport and Communications have jointly adopted policies for digital television. Both ministries agreed that no monopoly would be permitted. A national digital platform will be a joint venture with all interested Greek parties, with the state controlling no more than 50 percent of the shareholding. It is the government's intention that the digital platform covers 100 percent of Greek territory, offers programs for Greeks living overseas, and develops domestic digital technology and industry.

Electronic News Media

Electronic publications are a part of the Greek media. Diaspora WWW Project is a bimonthly electronic publication that provides information on Hellenism. It began publication in October 1994. Matsakoni, To is a Greek nonprofit magazine about social movements for human rights and social liberation, and is against alienation and the hunt for profit. Monopoli magazine is an electronic publication about music concerts, cinema, restaurants, exhibitions, and other cultural activities. Strategy magazine centers on the Greek military and the defense industry. Hellenic Resources Network (HR-Net) is a project facilitating communication between Greeks and the exchange of news and information pertaining to Greece and neighboring countries. I-Boom finds anything Greek or Greek related on the web. Greece-News Collection provides news related to Greece. Ariadne Hellenic News Base offers news from well-known Greek radio stations and news agencies in both Greek and English. Michailidis Publications is a business and trade publication for wholesalers and retailers of consumer goods. SV2AEL-Sava Pavlidis is an electronic publication of photographs, awards information, and the history of Thessaloniki. Recent additions to Greek Internet Media are Reporters Corner on-line Magazine , Eco2Day: Economy News, NetNewsNetDailyI-noteMetapolis , and The Media Zone .

The Greek Media offers Internet portals, which provide information online. These resources include HRI: Hellenic Directories & Portals, in.gr, Flash.gr, e-one, iboom Network (in Greek), iboom Network (in English), Pan.gr, Pathfinder, e-go, and Thea.gr. Online media directories are HRI: Newspapers and Magazines, Greek Media Index, The Reporter's Corner, The Greek Electronic Media Finder, Media Listings, Local Press, APN-report, Thea: Media Directory, Phantis: News and Media Directory, Eidiseis.net (multilingual), Rhodos Net: Media Index, and Mdataplus: Greek and World Press.

There has been a recent proliferation of online Greek newspapers and magazines. Online Greek newspapers include Kathimerini and Kathimerini-H.-Tribune in English, Ta Nea , To Vima, Athens News , in English, Eleftherotypia , Avgi Rizopastis, Agelioforos, Adesmeftos Typos, publisher K. Mitsis and Adesmeftos Typos , publisher D. Rizos, Apogevmatini , Ethnos, Express, Imerissia, Naftermporiki, Prin , and Athener Zeitung , in German. Many of these online newspapers are an electronic extension of long established newspapers already in print form. The intent is to expand readership by offering an online version. Greek online magazines, some associated with a publishing group, are HRI: Journals on Hellenic Issues (English), Thesis: Daily On-Line Journal of MFA (English), Defensor-PacisLambrakis Press, New Europe (English), Oikonomikos Taxidromos , Evropaiki Ekfrasi (Greek and English), Anti (Greek and English), Nemecis , MetroDefence and DiplomacyPegasus

Publishers , Compupress Publishers (Greek and English), and Stratigiki Publishers .

Education & TRAINING

Greeks seeking a career in the media and communication attend either the University of Athens, Panteion University in Athens, or Thessaloniki University in Thessaloniki. The Department of Communication and Mass Media at the National and Capodistrian University of Athens was founded in 1990 and offers a Bachelor, a Masters, and a Doctoral Degree in Communication and the Media. Athens' Panteion University has a relatively new program in Communication and Mass Media that offers a bachelor's degree. The Aristotle University of Thessaloniki was established in 1991 and offers a bachelor's degree in the Media in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication. Thessaloniki cooperates with a large number of European Union universities through the Socrates/Erasmus programs, enabling Greek students to attend universities in other European Union countries. Both Panteion University and the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki offer radio webcasting, and each university has its own radio station and electronic media lab.

Summary

The Greek media has undergone a rapid transformation within a quarter-century. A proliferation of privately owned media exists in all forms. The media in Greece is characterized by an industry that has modern technological equipment in use, high quality printed matter, major publishing houses, a low penetration of imported printed matter in the local market, and an improved financial picture for most media owners. The Greek media is plagued

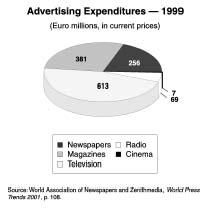

with reader disinterest resulting in lower circulation for most printed matter. There is a high dependency among the printed media on imported and expensive paper and ink. Newspapers continue to experience a high percentage of unsold newspapers, which increases production costs. The print media is too dependent on advertising revenues to balance costs; there is inadequate display and promotion, a high labor cost, and an insufficient utilization of production equipment. Since 1990 advertising expenditures represent a significant decline for newspapers and magazines. Advertising expenditures for radio fluctuates, while television advertising has steadily increased.

Greek newspapers comprise political, financial, foreign language, satirical, and sports editions. Newspapers on politics represent the largest share of the print media, but their sales continue to decline, followed by newspapers on sports. Only foreign language publications among Greek newspapers witnessed an increase in circulation. Since 1992 specialized magazines are almost 63 percent of the sales. General interest and children's magazines continue to decline in popularity. Professional journals in science, literature, and politics are seeking an audience, but their subscription numbers remain small. In an attempt to increase sales, newspapers are printing supplements in their Sunday editions that are strikingly like magazines.

Radio stations, state or municipally owned, continue to decline in popularity among Greeks. Most radio stations are privately owned with some failing to file for a license to broadcast. Deregulation undermined the government monopoly once existing over radio stations. Audiences continue to view private television networks over state television stations. Advertising revenues influence what is broadcast on private television channels. The quality of television programming continues to emerge as a national problem, with viewers complaining about too much time spent on advertising instead of programming. Rebates to attract viewers are coming under closer government scrutiny with some rebates being withdrawn because of the expense incurred.

The future direction of the Greek media will be affected by the policies adopted on proper licensing of broadcast media, cable television, and digital programming. The integrity and independence of the Greek media is directly affected by Greece's membership within the European Union. Within 25 years Greece has emerged from a political system, which institutionalized censorship and suppression, to become a democracy, which deregulated the media and is experiencing many of the same issues confronting the media as its national counterparts in Western Europe and the United States.

Significant Dates

- 1994: Creation of the Ministry for Press and the Media.

- 2004: Press coverage of the Olympic Games.

Bibliography

Cosmetatos, S. P. P. The Tragedy of Greece . New York: Brentano Books, 1928.

Curtis, Glenn, ed. Greece: A Country Study . Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1995.

Hourmouzios, Stelio. No Ordinary Crown . London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1972.

Kaloudis, George Stergiou. Modern Greek Democracy . New York: University Press of America, 2000.

Kousoulas, D. George. Greece: Uncertain Democracy . Washington, DC: Public Affairs Press, 1973.

"Local Newspapers, Magazines' Battle to Attract Readers." Hermes February 1999: 4-14.

"Mapping the Media Revolution." Hermes October 1996: 8-17.

Nash, Michael. "The Greek Monarchy in Retrospect." Contemporary Review September 1994: 112-121.

Papadopoulos, M. George. Two Speeches . Athens: 1967.

Papandreou, Andreas. Democracy at Gunpoint: The Greek Front . Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1979.

Papandreou, Margaret. Nightmare in Athens . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1970.

Papathanasopoulos, S. "Mass Media in Greece." In- About Greece . Athens: Ministry of Press and Mass Media, 2001.

Tantzos, G. Nicholas. Konstantine . New York: Atlantic International Publications, 1990.

Turner, Barry, ed. Statesman's Yearbook 2002 . New York: Palgrave Press, 2001.

Vaitiotis, P. J. Greece: A Political Essay . Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 1974.

Woodhouse, C. M. Modern Greece, A Short History . London: Faber and Faber, 1968.

——. The Rise and Fall of the Greek Colonels . New York: Franklin Watts, 1985.

World Mass Media Handbook, 1995 Edition . New York: United Nations Department of Public Information, 1995.

William A. Paquette