Resaca: May 15, 1864 (original) (raw)

A massive attack by two Union Corps hammers the Confederate line and is repulsed in heavy fighting. For one Confederate artillery battery this would be its final day of service in the Southern army. Brave men die on both sides fighting for possession of it. A second Confederate attack is foiled by a Federal flanking manuever. The position at Resaca becomes untenable.

The final day of the Battle of Resaca dawned with both sides intending to attack on the north end of the battlefield. Johnston hesitated, however, pending word on whether or not Sherman had outflanked him at Lay's Ferry. Johnston reissued orders for Hood to attack about noon, augmented by a brigade each from Polk's and Hardee's Corps (Secrist, p. 47). Before these orders could be acted upon, however, Sherman sent in Hooker XX Corps and Howard's IV Corps against Hood's Corps.The rest of the battlefield would remain quite except for occasional skirmishing and exchanges of artillery.

The Union plan was to drive the Confederate line southward toward Resaca while McPherson and Thomas pinned the Southerners before them in place. The hope was to turn the Confederate position and destroy the army against the Oostanaula River. Howard's troops began the assault around 1 p.m.

They attacked Hindman's division whose left flank had been tested in a portion of the previous day's attack. According to historian Albert Castel: "Three of Howard's brigades 'leap' their works and advance toward Hindman's Division which holds a hill just beyond the road at a point where it curves slightly to the northeast. Immediately, to quote Brigadier General William B. Hazen, the commander of one of the brigades, 'a concentrated fire of great violence' hits them. One-hundred and twenty of Hazen's men go down in thirty seconds, and he orders the rest to return to their fortifications." (Castel, p. 173)

Howard's initial attack failed in spite of a massive barrage throughout the morning by Federal artillery to "soften up" the Confederate position. The fire must have been extremely galling because it led the Confederates to make a momentous decision. Hood, in an attempt to offer some relief to Hindman's men with counterbattery fire, ordered Captain Max Van Den Corput's Cherokee Artillery battery be placed in advance of the Southern lines.

|

|---|

| Major General Carter L. Stevenson |

Stevenson, the division commander immediately on Hindman's right flank, recorded the occurrence in his official report: "During the course of the morning I received orders to place the artillery of my division in such a position as would enable it to drive off a battery that was annoying General Hindman's line. Before the necessary measures for the protection of the artillery could be taken, I received repeated and peremptory orders to open it upon the battery before alluded to. Corput's battery was accordingly placed in position at the only available point, about eighty yards in front of General Brown's line. It had hardly gotten into position when the enemy hotly engaged my skirmishers, driving them in and pushing on to the assault with great impetuosity. So quickly was all this done that it was impossible to remove the artillery before the enemy had effected a lodgment in the ravine in front of it, thus placing it in such a position that while the enemy were entirely unable to remove it, we were equally so, without driving off the enemy massed in the ravine beyond it, which would have been attended with great loss of life." (OR No. 653)

While Howard reformed and again launched an attack at Hindman, Hooker's XX Corps was finally arranged in the difficult terrain sufficiently to launch it's own assault. This fell upon Stevenson precisely at the moment Van Den Corput's Battery was most vulnerable. As Stevenson reported, the battery ended up in no man's land between the two forces. During the afternoon, the Northerners sent three different brigades forward in an attempt to capture and hold the four 12-pound Napoleon guns. They included an enthusiastic charge by the 70th Indiana under the command of Colonel Benjamin Harrison, future president of the United States. The first two attacks fail completely. As Castel put it: "Taking the cannon is one thing; keeping them is another. From the top of the hill and both flanks the Confederate infantry - tough Tennesseans of Brown's Brigade of Stevenson's Division - pour volley after volley into the presumptuous Federals, who scramble bank over the embankment and seek shelter on the other side." The final attempt was made by Colonel David Ireland's of Geary's division who "does not even try to reach the battery: instead it lies down fifteen yards away and opens fire on the enemy breastworks atop the hill, inflicting few casualties but forestalling an attempt by the Confederates to retrieve the guns. 'Come on - take those guns!' taunts Brown's Tennesseans. 'Come and take 'em yourselves!' the Federals yell back." (Castel, p.175)

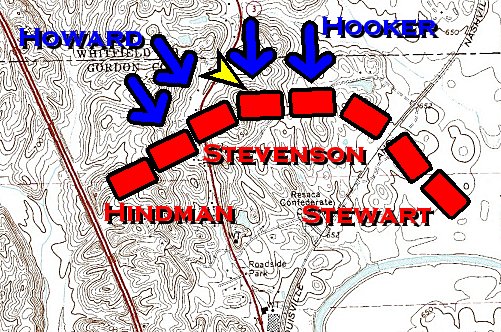

|

|---|

| The massive Union attack by the IV Corps and XX Corps upon Hood's Corps on May 15, 1864. It is repulsed by the two firmly entrenched Confederate divisions it encounters. The yellow arrow indicates the approximate position of van den Corput's four-gun battery that was captured by the Federals at the end of the day. The two parallel lines running of the left side of the map is Intersate 75 today. To the east, running up the center of the map is US Highway 41. North is up. |

"�Corput's battery became the scene of a holocaust," states Phil Secrist, "produced by the simultaneously advancing and constantly reinforcing columns of blue and gray. Colors were planted near the guns time and again, then lost and recovered as the outcome of the bitterly fought contest for the guns remained in doubt. Sergeant Frederick Hess, color bearer for the 129th Illinois of Butterfield's division, chagrined to hear the shrill triumphant cry of the Confederates, at once unfurled his flag, swinging it toward them in defiance. He instantly fell, but other hands grasped the flag, and it came back only to return and wave from the very spotwhere its former bearer fell." (Secrist, p. 55)

Hooker's attack of some 16,000 strong has been repulsed along with that of Howard's Corps by two Southern divisions. Stevenson summarized the results as follows: "The assaults of the enemy were in heavy force and made with the utmost impetuosity, but were met with a cool, steady fire, which each time mowed down their ranks and drove them back, leaving the ground thickly covered in places with their dead." (OR No. 653) Hooker lost some 1,200 men, 156 of which were in Colonel Harrison's attack on Van Den Corput's now isolated battery. (Castel, p.175)

Having blunted Sherman's main blow for the day, thus disrupting the entire Union plan for the battle, Johnston's orders for Hood to go over to the offensive were then acted upon. Stevenson, naturally had difficulty aligning his men for the attack, as he was heavily engaged until about 3 p.m. when the Union fire finally abated to a skirmish. Stewart, meanwhile, had seen little action during the day and was ready to lead the charge. It began about 4 p.m. with Johnston once again hoping to turn Sherman's left and cut him off from Snake Creek Gap.

According to Bill Scaife: "Stewart moved out in the same half wheel maneuver used the previous day - with Henry Clayton's brigade on the left, supported by Randall Gibson's brigade, and Stovall's Brigade on the right, supported by Alpheus Baker's brigade. George Maney's brigade of Cheatham's division and the 11th Tennessee Cavalry Regiment under Colonel Daniel W. Holman supported Stovall's right flank. Captain Thomas J. Stanford's Mississippi Battery went into action behind the center of Stewart's Division. While the attack was under way, Johnston received another dispatch from General Walker, informing him of Sweeny's second crossing of the Oostanaula and - since Sweeny might easily cut the railroad bridge at Resaca - Johnston called off the attack and began preparations to withdraw from Resaca. But Stewart's men were already committed and suffered heavy losses during the withdrawal - including Captain Thomas J. Stanford, who was killed while commanding his Mississippi Battery of Artillery." (Scaife, p. 36) (See LAY'S FERRY for further explanation of Sherman's maneuver that ultimately made Johnston's position at Resaca untenable.)

Stewart's losses were close to 1,000 killed, wounded, and captured with an additional 100 casualties in Stevenson's supporting division. It was a heavy price to pay for what was, ultimately, an aborted effort. The Union troops sustained over 400 casualties in repulsing the assault. (Castel p. 178)

So ended the dreams of both commanders at Resaca. Johnston's intention of cutting Sherman off from his lines of communication resulted in utter defeat except for the fact that it forced Hooker's large Corps to shift away from Resaca and further to the north where it was comparatively less threatening. Sherman's hope of crushing Johnston's army north of the Oostanaula was met everywhere with failure except for limited success on Polk's front on the May 14 and the symbolic success of capturing four artillery pieces hastily placed under Hood's orders.

|

|---|

| Colonel George A. Cobham, his command actually captured the four Napoleon guns of Corput's battery. |

Those guns were still trapped between the armies, however, as dusk settled upon the battlefield, their fate very much in doubt. General Geary's official report describes in detail how the guns were finally captured in spite of the counterattack that was eventually launched by Stevenson's division in support of Stewart: "In the isolated position held by Cobham it was impossible to erect even a slight barricade without receiving a terrible fire from the enemy fifty yards distant. In front of my left and Williams' right was a long, cleared field occupying two hills and a narrow ravine, and extending to a wooded hill on which was the enemy's main line. In front of my right was a field occupying a long, wide ravine, extending from the right of my line to a cleared hill on which was also the enemy's main line. Through this ravine ran the road previously referred to. Across the ravine to my right were lines of intrenchments held by the Fourth Corps and facing nearly eastward at right angles to my front. In front of the center of my main line a series of timbered spurs and knobs extended half a mile toward the enemy's main lines to the detached position held by Cobham. The troops sent to his support by me were so disposed as to hold his flank as well as possible. The only route of communication with him was by way of these timbered ridges, which were swept in most places by musketry and artillery fire from the enemy's main lines. About 5 p. m. the enemy (Stevenson's division) debouched from the woods in front of my left and General Williams' right, and charged in column with the effort to gain possession of the ridges in our front. The attempt, if successful, would have exposed Cobham to attack from every side and have forced him to abandon his position, but the enemy's attack, though a spirited one, failed. A tremendous fire concentrated on him from the lines of my division and those of General Williams' almost destroyed his leading regiments (of Brown's rebel brigade) and sent the attacking column back in confusion to their intrenchments, after half an hour of sharp fighting. In this affair the artillery on both sides took an active part, canister and shrapnel being principally used. During the engagement Colonel Ireland was wounded by a piece of shell, and the command of his brigade devolved upon Colonel Cobham. That officer being already intrusted with the command of six regiments and the special work of securing the battery in his front, I directed Col. William Rickards, commanding Twenty-ninth Pennsylvania Volunteers, to assume command of such regiments as remained in the main line. Wheeler's battery had taken position in my line behind log works constructed for the purpose. About dusk Colonel Cobham reported to me in person and received instructions to dig through the works in front of the guns and bring them off with drag-ropes during the night. The necessary tools and ropes were sent out and the work performed with alacrity and tact by the officers and men under his immediate supervision. In the darkness of the night the men crept silently on hands and knees to the little fort and carefully removed the logs, earth-works, and stones in front of the four guns. At midnight all was ready. The drag-ropes were attached and manned; a line of brave men lay with pieces aimed at the crest of the hill, and at one effort the guns were drawn out and taken rattling down the hill. The enemy on the alert, sprang over their breast-works and furiously attacked Cobham's line. The sharp musketry fire aroused all our troops. Those in the intrenchments to our right across the ravine, not knowing the meaning of it, evidently believed it to be an attack upon their main line, and opened a tremendous musketry fire, much of which poured into Cobham's lines from his right and rear. Word was quickly sent themand their firing was stopped. Cobham held his position, drove back the enemy, and sent the guns, four 12-pounder brass pieces, to my headquarters." (OR No. 204) Note: This report often refers to the brigade of Colonel George A. Cobham, Jr.

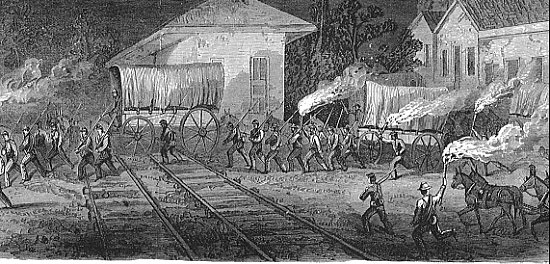

With his position flanked (see LAY'S FERRY), Johnston had little choice but to pull out of Resaca. He did so skillfully, leaving absolutely nothing of value for the Union troops behind but for his lost battery. (Scaife, p. 37) About 3:30 a.m. on May 16, the Confederates set fire to the bridge, thus destroying what Union artillery could not from a distance throughout the course of May 15.

It was with a heavy heart that the Army of Tennessee abandoned the strong position it held at Resaca. Colonel Robert P. McKelvaine of the 24th Mississippi was part of Hindman's divison that had defended against fierce Federal attacks on both May 14 and 15. He closed his official report on Resaca with these words: "At about 10 p. m. on this day we moved out of our trenches and began our retreat from the blood-dyed hills of Resaca, and not a heart but heaved a sigh of regret at abandoning a spot where we had struggled so hard for thirty-six hours for our common country's cause-a spot consecrated by the life-blood of so many of the best and bravest of our comrades in arms; but as we looked for the last time upon their graves, and knew that the vandal foe would tread upon them on to-morrow, [we felt] that they had not fallen in vain."

The fury of the Confederate resistance at Resaca made a profound impression upon Sherman's mind throughout the rest of the campaign. It would be five long weeks before the Union commander would try another major assault upon any entrenched Southern positions. The nature of the War Between the States had changed forever. It was now a matter of trench warfare that the rest of the world would not come to understand until some 50 years later in Europe.

Wagon Train Passing Resaca at Night by A. R. Waud