Sautet, Claude – Senses of Cinema (original) (raw)

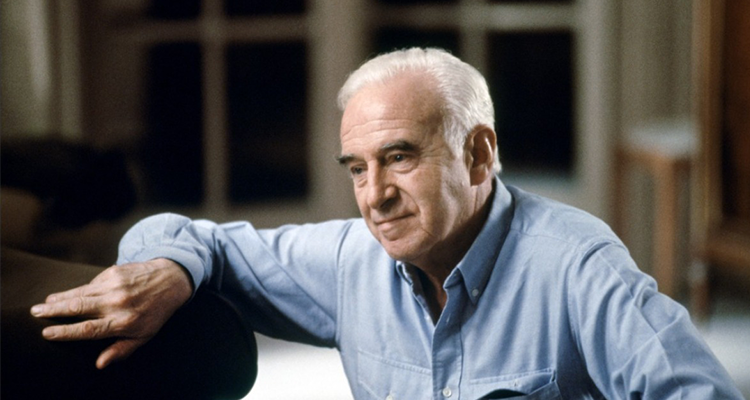

b. February 23, 1924, Montrouge, Hauts-de-Seine, Île-de-France, France

d. July 22, 2000, Paris, France

filmography

bibliography

articles in Senses

web resources

The Poetics of Melancholy

There is a sense of melancholy and a certain quietude that permeates Claude Sautet’s cinema, and it is in keeping with its pace, a languid but deliberate slowness, that we are able to enter into his world. Sautet’s world is a richly textured one, and requires attentiveness and a careful eye to its details. Populated by fully formed and complex characters, its skein of images is the weaving together of a series of looks, gestures, annunciations, utterances and moods of its inhabitants. Both limpid and opaque, this world and its denizens ask us to be thorough and mindful not only of what we see, but also what we hear — to listen to the conversations, the music, the ambience, as well as the silences. In this way, his films ask us to surrender our senses, to give ourselves over to them, so that we do not remain on the ‘outside’ as mere viewers or voyeurs to the intimacy on screen.

Described as a “discrete and elegant man,” (1) for many this director is a humanist whose films may be described as “intimate-realist” (2) films, a meticulous study of lived lives whose characters, despite their social standing, are nonetheless part of the quotidian. Who is to say that the bourgeoisie are immune to the falterings of friendship or the failings of love? For others, his films are scrutinised for their lack of criticism of the bourgeoisie and their mores, and whose films always seem to be “as pleasant, polite and polished as the man himself” (3) and are “very French in that attractive, fashionable people prepare and eat a lot of attractive food, while grappling with life and love” (4) kind of way. It is these kinds of split considerations that have haunted Sautet’s career and driven a rift between the two French film journals, Positif and Cahiers du cinéma, in their views and opinions of this French director. It seems that, for the latter, Sautet has simply vanished out of sight — especially in death, with the noticeable absence of obituary on this important director.

Perhaps it does not matter ultimately whether Sautet chooses to comment on or embrace the upper middle class. His work is unlike that of Chabrol’s or Buñuel’s, it is not there to lend a critical eye or to satirise. Instead, we find a kind of honesty and humility in his films that do not bear on the side of judgement.

Sautet began his career outside of the film industry. As a boy, he was very passionate about the fine arts, he took to making sculptures and then moved onto painting film sets. After the liberation, his career took a different turn: he worked as a social worker after joining the Communist Party (which he left in 1952), but remained interested in the arts, this time his interest shifted to music, an interest which remained with him for the rest of his life. Between 1949 and 1950 he worked for the leftwing journal, Combat, as a music critic. Sautet claims that he owes his love of the cinema to his grandmother, a film enthusiast, and after a chance meeting with a film editor during the war, Sautet’s interest in filmmaking began in earnest. He claims that it was the film Le Jour se lève (Marcel Carné, 1939) that remained the “decisive factor that made [him] tumble into that strange profession.” (5) In his mid-20s, the newly formed Institute des Hautes Etudes Cinématographiques (IDHEC) gave him the opportunity to study the different aspects of filmmaking. He made his first short film, Nous n’irons plus au bois (1951), before working for almost ten years as an assistant director to a number of directors, most notably with Georges Franju in his film Les Yeux sans visage (1959). During this time he made his first full-length feature film, Bonjour sourire (1955), a comedy with Jean Carmet, Annie Cordy and Louis de Funès, which passed virtually unnoticed by his peers and critics alike. Sautet would have to wait until his next feature five years later with Classe tous risques (1960), before being recognised as a significant director. A police-crime story, this film with Lino Ventura (who will later become Sautet’s friend) and Jean-Paul Belmondo (fresh from his success in À Bout de souffle [Jean-Luc Godard, 1960]) gave evidence of Sautet’s strong sense of characterisation. But almost as soon as his career in directing began, another setback was already upon him. With the nouvelle vague movement in full swing, its band of experimental and exciting filmmakers, such as Godard, Truffaut, Rivette and Chabrol, brought a breath of freshness to French cinema, and with this important turning point in French film direction, the critics saw Sautet’s style as too orthodox and somewhat passé.

Sautet withdrew from directing his own films and took to scripting in the intervening years, and, though little known publicly, within the industry he was perhaps more distinguished for his ability and work in transforming a script than his work as a director. Often called upon by fellow directors to dislodge their writer’s block (Marcel Ophüls, Jacques Deray and Jean Becker are amongst a few), he earned the reputation and title of “script-doctor” from Truffaut. Much of his work in this period (and a lot of his dialogue work in the ’60s remains uncredited) concentrated on developing and perfecting dialogues and observations on love in its various dimensions. His delicately nuanced study of love resurfaces in his own films in the ’70s and again in the ’90s.

Les Choses de la vie (1969) marked the turning point for Sautet. He had found his muse in the Austrian-born actor Romy Schneider, who went on to star in many of his films in this period, including Max et les ferrailleurs (1971), César et Rosalie (1972), Mado (1976), and Une Histoire simple (1978) which won her a best actress César (the film was nominated for 11 Césars). It is also in this period, which is perhaps his most productive and fruitful in that he founded long-term friendships with actors Michel Piccoli and Yves Montand, and with his collaborators, scenario-writer Jean-Loup Dabadie, cinematographer Jean Boffety and composer Phillipe Sarde. As with his careful depictions of human relationships in these films, Sautet greatly valued his personal friendships and that is why most of the time he chose to work with people he knew, or whose work he was familiar with. Romy Schneider’s suicide in 1980 affected him very deeply, and his work slumped to a low point with Garçon (1983), which was not well received either by the public or critics.

His last three films, Quelques jours avec moi (1988), Un Coeur en hiver (1992), and Nelly & Monsieur Arnaud (1995) saw Sautet with new-found friendships in actors Daniel Auteuil and Emmanuelle Béart, and writer Jacques Fieschi. Somewhat belatedly, it was only his last two films that brought international critical acclaim to this director — both films were nominated and won a host of French and foreign awards, including the Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival for Un Coeur en hiver and the prix Louis Delluc for Nelly & Monsieur Arnaud.

Claude Sautet passed away on July 22, 2000 after a long battle with liver cancer. He is survived by Graziella Escojido, his wife of 47 years, and a son, both of whom he took care to shelter from public life. In an homage to Sautet, President Jacques Chirac described his work poignantly, and hailed the director as one who “held out the mirror of our times.”

For me, his films have the ability to consume us entirely, by stripping back our emotions we come face to face with something truthful in his films. From the first moments of Un Coeur en hiver we are engulfed by the long takes, the stillness of his images and the whisperings of his characters. It is as though we are bound by some secret affinity to the lives of these characters.

In an interview Sautet revealed that this film was more based on his memories of the story, rather than an adaptation of Lermontov’s short story “Princess Mary,” from his book A Hero of Our Time. This aspect, coupled with Jean-Jacques Kantorow’s recording of Ravel’s sonatas (a gift from his son, which he was listening to at the time), allowed Sautet’s film to develop deeper and richer dimensions in the three main characters. The novelistic quality in the detailed study of his characters, who reveal themselves slowly but precisely, through conversations, gestures, looks, are all Sautet’s doing. He and writer Jacques Fieschi worked on the first third of the dialogue for no less than four months in order to pare it down to perfection.

But there remains an opacity to his characters: we learn of Stéphane’s (Daniel Auteuil) thoughts about winning over Camille (Emmanuelle Béart) through snippets of his conversations with Hélène (Elisabeth Bourgine), but his gestures and behaviour belie his stated intentions (standing silently in the dark watching his old professor argue with his wife). We do not know whether we should believe in what he says, or even if he himself understands his own actions.

The slow disintegration of the relationship between this “enigmatic, self conscious and meticulous musician and collector of mechanical toys” (6) and his partner Maxime (André Dussolier) is as unbearable to watch as Béart’s luminosity is beguiling. But the threesome (Stéphane, Camille and Maxime) hangs onto each other, and their story can only be told with all three of them in their place. So, as painful as it is to watch Camille’s fall towards Stéphane’s cruel detachment, it is somehow unavoidable for their love to be unfulfilled and unable to be reconciled.

It is in the same vein that Sautet poses impossible situations to us: how are we to choose between Samy Frey and Yves Montand, who are both in love with Romy in César et Rosalie? And the stolen moments of love in the face of loneliness for Nelly (Emmanuelle Béart) and M. Arnaud (Michel Serrault). Love for Sautet is not about knowing where it will take you. His camera observes a world where human subjectivity is something unknowable. We can only ‘gaze upon’ what he reveals to us in the hope that, like his characters, we may come to know this person that is not ‘I’, but who is other and thus unfathomable. Sautet’s films are a careful study of human subjectivity and reflect our struggle to find meaning and love in our often complex, difficult and fragmented relationships through life.

The intimacy and love between Nelly and M. Arnaud is beautifully captured by Sautet in the scene where Nelly half-wakes from sleep and sees Arnaud sitting beside her bed. Instead of an encounter of passion, we find her falling back to sleep holding his hand, as a child would, for comfort. The camera stays on a shot of Arnaud watching her sleep. His face is tender, but impassive. If we look at this scene carefully, taking in M. Arnaud’s silence and the way he looks at her, we will know that he loves her, deeply, but that their relationship is not meant to be. And, it is at that moment when he comes to a realisation that he must set her free. Love, when stripped bare, is often a sobering experience. In its being truthful, it is inevitable that it also contains our disenchantments.

For me, however, it is Sautet’s work on Les Choses de la vie that helps change the French cinematographic landscape definitively. Who can forget and not be haunted by those quiet, infinite rebounds of Piccoli’s car? Its slow-motion drags this moment across almost the entire film. When we see it in ‘real-time,’ it is no more than four or five seconds in duration. We are almost always shocked by its speed, the force of it and the incredible deafening sounds. What, in effect, are we seeing in these slow-motion replays? I would suggest that they are more than images repeating or folding in on themselves. These rebounds, which stretch out infinitely, are already in the realm of memory, and contain within them images which map out Piccoli’s existence, the fragmented episodes of love, his family and their drifting apart, his isolation. These images cannot merely be ticked off as having ‘your life flash before your eyes’ at the moment of your death. They are images which describe a life not “as it actually was, but a life as it was remembered by the one who had lived it.” (7)

You see, Piccoli’s character is also this past that is in his memory. Between each rebound of the car, Sautet reveals to us the fabric of this man’s existence, and makes present to us a part of him which up until now has remain hidden. To borrow one of Romy’s lines, these images are “full of memories that don’t belong to me.” (8) These memories that “don’t belong” to her are precisely the memories that she is jealous of, because she has no way of knowing them. She will never be able to recall Piccoli’s past. Barthes describes this perfectly: “I cannot open up the other, trace back the other’s origins…Where does the other come from? Who is the other? I wear myself out, I shall never know.”

For Walter Benjamin, the remembered past is infinite and as unknowable as the future. Sautet conveys these ideas beautifully in two image-sequences in Les Choses de la vie. There is a long-take towards the last third of the film, where we see Piccoli through the windscreen of his car, the camera pulls away from a close-up of his face and continues to pull back until we are able to see the bonnet of his car. Quickly accelerating, it picks up speed and zooms away from the car until only an outline of it is visible, the camera then pans quickly to its left. Dappled sunlight and a blur of leaves fill the screen as it continues to pan left. The frame suddenly pulls clean away from the tree tops: an open sky fills the screen entire. All movements cease. We have arrived, it is the future.

Another long image sequence conveys the notion that the past is infinite. It is the title sequence which continues to haunt me with every viewing, as we are displaced by what we see. I remember being totally absorbed by the image, but was unable to work out what I was actually seeing. It is simple, the camera looks out through the windscreen of the car, we are driving, a long time passes, the light changes, cars pass and keep passing on both sides of the road. The entire sequence is played backwards through the projector. It seems that we are being pulled outside of time — our experience of spatio-temporal relations are completely out of kilter. It may be that this sequence is trying to convey a travelling back in time. But for me, this image-sequence will always remain an enigma. These images of the passage of time and Phillippe Sarde’s incredibly beautiful music transport the viewer into their own subjectivity. Whilst watching this scene, I somehow always find myself in my own memory — remembering two other unforgettable and solicitous car sequences. The first one is in Antonioni’s The Passenger (Antonioni, 1975), where Maria Schneider asks Jack Nicholson what he is running away from, and he tells her to turn around and look behind her. The image cuts to her POV and one sees the long stretch of road rapidly pulling away from them. It is the past, a past which has made her who she is, that which constituted her identity. The other sequence is from Catherine Breillat’s À ma soeur! (Catherine Breillat, 2001), the sisters in the car are sullen and waiting, we see the world literally passing them by in the side-mirror of their car. What a simple shot, and yet, we are able to sense their already protracted and doomed future from the silent mood of the girls and the fleeting images in the mirror.

Sautet conveys to his viewers the same kind of sentiments through dialogue and framing. Piccoli’s quiet and broken utterances after his accident in _Les Choses de la vie_—“I’m hot,” “shall I open my eyes?” “maybe I’ll rest a little,” “I’m hot,” “who put this blanket on me?” “I’m thirsty,” “I’m hot”—shows a man in ruins more effectively than any image of a bloody and broken body can. The camera picks out parts of his body in a series of close-ups, his still fingers, his closed eyes, his face down in the grass, his fingers again.

The yearning, or suffering, of Stéphane’s heart in Un Coeur en hiver is revealed to us through Sautet’s close-ups of Auteuil. His choice of a sombre palette of winter tones, grey-brown and desolate, rather than steely blue tones, and the grace and melancholy of Ravel’s music all infuse the film with a kind of warmth which seem to suggest that Stéphane’s heart is capable of love. Most of the time his unyielding exterior is echoed in his gestures, although if one studies his behaviour closely, one will find that these are also gestures which give him away: his immobility in the presence of Camille and his silent repose beside Maxime may suggest a steely heart, but he is ultimately betrayed by those burning eyes of his when they are fixed on Camille, and by his patience and fine ear for Maxime and music. And, finally, an act of kindness he kills his sick old professor. Though morally wrong, Sautet believes that this is the only “compassionate and loving thing he does” in the film, because his character is “incapable of any positive action in a conformist sense.” (9) Sautet goes on to say that although it is impossible to know how deep Stéphane’s love is for Maxime, one is able to get a glimpse of this love through his look of childlike bewilderment when Maxime comes to visit him in his new studio and from the gravity of these short words Stéphane says to Camille at the end of the film: “You’ve missed me, and I’ve lost Maxime.” (10)

This is what Sautet’s films do best, to reveal to us that “the other is not to be known; his opacity is not the screen around a secret, but, instead, a kind of evidence in which the game of reality and appearance is done away with.” (11) He achieves this through carefully constructed dialogue and the way he frames his characters: never in the middle of the action, but always on the sidelines, waiting and watching silently, humbly and without judgement. It is in these ways that his images allow us to approach the other without eroding their opacity. For the enigma of the other is precisely what intrigues us; we need them to be different from ourselves, so that we may be “seized with that exaltation of loving someone unknown, someone who will remain so forever.” (12) Like the closing of a violin, “[e]verything, all the work that has gone on underneath, is hidden. The skill of the craftsman is such that it takes two people to close up the instrument.” (13)

Claude Sautet’s cinema is an intimate one, and like the perfume on a lover’s skin it is ephemeral and fragile, and yet, traces of it remain with you, lingering like an afterimage.

Filmography

Films directed by director:

Nous n’irons plus au bois (We Won’t Go to the Woods Anymore) (1951) short film

Bonjour sourire (1955)

Classe tous risques (The Big Risk) (1960) also writer

L’Arme à gauche (Guns for the Dictator) (1964) also writer

Les Choses de la vie (The Things of Life) (1969) also writer

Max et les ferrailleurs (Max and the Junkmen) (1971) also writer

César et Rosalie (César and Rosalie) (1972) also writer

Vincent, François, Paul… et les autres (Vincent, François, Paul and the Others) (1974) also writer

Mado (1976) also writer

Une Histoire simple (A Simple Story) (1978) also writer

Un Mauvais fils (A Bad Son) (1980) also writer

Garçon! (Waiter!) (1983) also writer

Quelques jours avec moi (A Few Days with Me) (1988) also writer

Un coeur en hiver (A Heart in Winter) (1992) also writer

Nelly & Monsieur Arnaud (Nelly and Mr. Arnaud) (1995) also writer

OTHER CREDITS

Le Mariage de Mademoiselle Beulemans (The Marriage of Mademoiselle Beulemans) (André Cerf, 1951) assistant director

Le Fils de Caroline chérie (Caroline and the Rebels) (Jean Devaivre, 1955) assistant director

La Bande à papa (Guy Lefranc, 1955) assistant director

Les Truands (The Gangsters) (Carlo Rim, 1956) assistant director

Action immédiate (To Catch a Spy) (Maurice Labro, 1957) assistant director

Le Fauve est lâché (The Beast Is Loose) (Maurice Labro, 1959) co-writer

Les Yeux sans visage (Eyes Without a Face) (Georges Franju, 1959) co-writer and assistant director

Peau de banane (Banana Peel) (Marcel Ophüls, 1963) co-writer

Symphonie pour un massacre (The Mystifiers) (Jacques Deray, 1963) co-writer

Échappement libre (Backfire) (Jean Becker, 1964) co-writer

L’Âge ingrat (That Tender Age) (Gilles Grangier, 1964) writer (story)

La Vie de château (A Matter of Resistance) (Jean-Paul Rappaneau, 1967) co-writer

Mise à sac (Pillaged) (Alain Cavalier, 1967) co-writer

La Petite vertu (A Little Virtuous) (Serge Korber, 1968) co-writer

Borsalino (Jacques Deray, 1970) writer

Les Mariés de l’an II (The Scarlet Buccaneer) (Jean-Paul Rappaneau, 1971) writer

Mon ami le traître (My Friend the Traitor) (José Giovanni, 1988) writer

Intersection (Mark Rydell, 1994) writer (earlier screenplay)

Select Bibliography

There is scant material written in English on this director apart from film reviews.

Claude Sautet, “_Le Jour se Lève_”, Projections 4 1/2, Faber and Faber, London, 1995

Interview by Michel Sineux Yann Tobin, “Claude Sautet on _Un Coeur en hiver_”, Projections 9, trans. Pierre Hodgson, Faber and Faber, London, 1999

Michel Sineux, “The Suburbs…Did You Say the Suburbs? _Vincent, François, Paul, and the Others_”, Positif 50 Years: Selected Writings from the French Film Journal, ed. Lawrence Kardish, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2003

Articles in Senses of Cinema

Claude Sautet’s Nelly And Monsieur Arnaud (1995) – An Appreciation by John C. Murray

Music of a Frozen Heart: Love and Disharmony in Un Coeur en hiver by Acquarello

Claude Sautet: Purity and Invention by A. Jay Adler

Web Resources

Compiled by author

Ecran Noir

Unfortunately in French again, but has a nice little interview with Sautet. Good selection of photographs and bio. A good bio and filmography on his actors are also available.

Positif Journal

For the francophile amongst us, there is a voluminous abundance of material—articles, reviews, interviews on this director. There is a search function on their home page which can lead you straight to the articles on the director.

Strictly Film School

A beautiful web resource, Acquarello’s love of Sautet is evident in his rich descriptions of two of his films, Vincent, François, Paul… et les autres and Un Coeur en hiver.

Urban Desires

Webzine with an interesting interview with Sautet and Béart on the filming of Nelly et Monsieur Arnaud.

Endnotes

- Le Web de l’Humanite, http://www.humanite.presse.fr/journal/2000/25.6, 20 January 2003

- Ginette Vincendeau, “Une Liaison pornographique: An Intimate Affair”, Sight and Sound, July 2000

- Ronald Bergan, “Claude Sautet”, The Guardian, 26 July 2000, from the Guardian Unlimited http://www.guardian.co.uk/obituaries/story/0,3604,347112,00.html, 11 January 2003

- Bergan

- This issue of Projections are excerpts from the 40th anniversary issue of Positif, in which directors that the magazine admired were invited to write a piece on what they love about cinema. Claude Sautet wrote about his experience of Le jour se lève, which he saw 17 times when it was first released. “The first day I saw it four times running, and left the theatre dazzled and crushed by a pain and a pleasure I couldn’t explain.” Claude Sautet, “_Le jour se lève_”, Projections 4 1/2, Faber and Faber, London, 1995, p. 194.

- Sautet talked about the reasons behind using the Ravel Trio and Sonatas for this film in several interviews. Interestingly, he chose the Trio and Sonatas because he felt that they were not particularly stunning, otherwise the music would distract the viewer too much. For him, this music reflected the moods and inner struggle of his characters. He played the recording to Fieschi during the preparation of the screenplay in order to convey something of its tone and mood. The Sautet quotes in text are from the CD slip insert for Jean-Jacques Kantorow’s recording of Ravel’s Trio & Sonates, Erato Disques S.A. Original recording 1973, re-release 1992.

- My emphasis. Walter Benjamin on remembrance, “The Image of Proust”, Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn, Fontana Press, London, 1973, p. 198.

- Here, Romy is referring to Piccoli’s house with his ex-wife on the island. She is intrigued and wants to go there, but at the same time she feels ill at ease, confronted by the unknown past of her lover.

- Interview by Michel Sineux Yann Tobin, “Claude Sautet on Un Coeur en hiver,” Projections 9: French Film-makers on Film-making, trans. Pierre Hodgson, Faber and Faber, London, 1999, p. 65

- Tobin, p. 66

- Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse, trans. Richard Howard, Penguin Books, London, 1990, p. 135

- Barthes, p. 135

- My emphasis, Tobin, p. 69