A Brief History of Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine (original) (raw)

A Salute to Asimov's SF and Analog, Part II

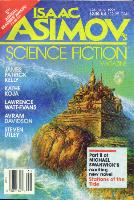

Click on any of the covers below for a larger image.

The Seventies

Art by Paul Alexander

Over the next several years, ASF published some superb fiction. George Scithers was awarded a Hugo in 1978 for Best Professional Editor, and in 1979 the magazine began publishing monthly. In fact, it was successful enough that Davis launched a sister publication, Asimov's SF Adventure Magazine. Although it lasted only four issues, ASFAM is fondly remembered -- not just for bringing backBefore the Golden Age-style pulp sensibilities long before it became trendy, but for its high production values (issues were regular magazine size, not digest, and the first three included fold-out colour posters by Paul Alexander) and for fine stories by folks such as Roger Zelazny, Samuel R. Delany, Poul Anderson, John Brunner, and Barry B. Longyear.

Art by Vincent di Fate

Back in the digest magazine, Barry B. Longyear was emerging as one of its first and most exciting new discoveries. In the six months between May and October of 1979 he landed the cover story fully five times -- a nearly unprecedented endorsement for anyone, let alone a brand new writer. And with the novella "Enemy Mine" in the September issue of that year, Longyear captured the Hugo, Nebula, and John W. Campbell Awards -- the first and only time an author had won all three in a single year -- and became the magazine's first home-grown star.

"Enemy Mine" is the tale of Willis Davidge and Jeriba Shigan, fighter pilots from opposite sides in a bitter interstellar conflict, who shoot each other down in the last dogfight of their lives. Stranded on a hostile planet, facing both a lethal environment and an alien enemy, both of them must chose between continuing the struggle... or surviving. The story was filmed in 1985, with _Dennis Quaid_as Willis and Lou Gossett Jr. as the Drac Jeriba, and Longyear followed his novella with several short stories and two novels, eventually collected together as the lengthy The Enemy Papers (White Wolf, 1998, 655 pages).

Art by George Barr

By the close of the decade, Scithers had established the tone of ASF, including its willingness to blur the boundaries between SF and Fantasy. Many genre publications -- the stalwart _Analog_in particular -- had built a loyal readership with their earnest dedication to a "pure" definition of science fiction, so it was often refreshing to find unrestrained flights of fancy between the pages of a mainstream SF magazine.ASF was different in other ways as well: it dispensed with the two-columns-per-page format popular at the time, sticking with a single column which gave the pages a more book-like appearance, and it published a variety of humour pieces. While it rarely offered science fact as such, it did have a lively puzzle column by none other than Martin Gardner. In addition, it stayed dedicated to short fiction, for the most part avoiding serialized novels that (while popular) ate up an enormous page count that might otherwise go to fiction that had no other venue.

Other popular stories in the early days of the magazine included "The Barbie Murders" by _John Varley_and "Cautionary Tales" by Larry Niven -- as well as the outrageous short short features "Through Time and Space With Ferdinand Feghoot!!" by "Grendel Briarton" (Reginald Bretnor). Theses latter pieces featured groaner puns and sharp wit... often in the same story. And while you rarely praised a Ferdinand Feghoot story (at least in public), you almost always read it first.

The Eighties

The 80s started off with a bang, as the emerging success of Asimov's encouraged Davis Publications to try again to build on its franchise -- this time through the purchase of the venerable Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact from Conde Nast Publications, which had owned it since the early 60s.

Art by Robert Crawford

This attempt proved much more successful. While Asimov's had an enthusiastic and growing audience, Analog's surpassed it -- it was (and remains to this day) the most consistently popular SF magazine in the field. Cross marketing and shared production resources between the two led to cost savings and more streamlined operation. Still, there was no shortage of surprise and even pessimism in the fan community. Suddenly the two most important publications on the field, traditionally friendly competitors, had eloped. Rumours abounded of further consolidations, cutbacks and mergers, sure signs of the coming genre apocalypse. When both magazines continued to prosper the prophets moved on, eventually fingering rampant E.T. merchandising and**Star Trek** novelizations as the instruments of Satan.

In 1980 Scithers won his second Hugo Award for Best Professional Editor. More awards for the magazine were to follow -- the next fiction Hugo was for the modern classic "Unicorn Variation" by Roger Zelazny, (April, 1981) selected just last year by the Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America as the third most popular fantasy tale of all time (behind "The Lottery" by Shirley Jackson and "Jefty is Five" by Harlan Ellison). It has most recently been reprinted in The Fantasy Hall of Fame (HarperPrism, March 1998) under its corrected title, "Unicorn Variations," and is still worth seeking out today.

Art by George Angelini

Changes were ahead for the magazine in the next few years. In April of 1981 it debuted a sparse new cover logo, and under new art director Ralph Rubino it gradually jettisoned traditional SF cover art for more representational work, such as the untitled George Angelini piece at left. While this approach simplified production and allowed the magazine to build up an inventory of cover art (since the pieces were no longer commissioned directly from stories), in general it didn't do much for the look of the magazine. By the end of 1992, **Asimov's**returned to a more conventional look for the cover.

Cosmetic changes weren't the only ones in store, however. The magazine changed editors several times -- first when Scithers left in March of 1982 and was replaced with Kathleen Moloney, and again less than a year later when Shawna McCarthy stepped up to the plate. In mid-1982 Sheila Williams was hired as Editorial Assistant (soon to be Managing Editor, and finally Executive Editor) and she has remained with the magazine ever since, the most stable fixture on the masthead for the past 15 years. But throughout all the changes the quality of the stories for the most part was uninterrupted, and by the early 80s Asimov's had earned a solid reputation for award-winning fiction.

Art by Val Lindahn/Artifact

Stories in this period included David Brin's justly famous "The Postman" (November 1982), a post-apocalyptic tale detailing the exploits of Gordon Krantz, survivor and scoundrel, who steals the uniform of a dead postal worker only to find himself clothed in that rarest of garments: hope. Brin followed the story with "Cyclops" in the March, 1984 issue, and then collected and novelized them asThe Postman the following year (a novel which inspired a Kevin Costner vehicle of the same name over a decade later -- but don't let that discourage you). In August of 1983 Gardner Dozois returned to the magazine, this time with his first fiction appearance: "The Peacemaker," a striking near-future story of a world where the polar icecaps have melted, raising sea levels nearly 300 feet and driving refugees ever inland... and a young boy who cannot shake the feeling that the great floodwaters are somehow chasing him personally. The story captured Dozois his first Nebula award.

Other famous pieces from this period include "A Traveller's Tale" by_Lucius Shepard_; "Fire Watch" by Connie Willis (winner of the 1982 Nebula and 1993 Hugo Awards); "Hardfought" (1983), hard-science writer Greg Bear's Nebula Award-winning novella of a distant future where humanity is locked in a millennia-long war with a thoroughly enigmatic enemy; and one of Dan Simmons first magazine appearances, the haunting "Remembering Siri" (December, 1983), the tale of a young veteran space traveller and the beautiful, mysterious girl he meets on a far world of the vast human Hegemony. Like Simmons' epic novella "Carrion Comfort," published a year earlier and eventually expanded into the groundbreaking horror novel of the same name, "Remembering Siri" was to be the seed for a vast project, eventually bearing fruit with two of the most famous SF novels of the decade:Hyperion (Doubleday Foundation, 1989) and The Fall of Hyperion, (Doubleday Foundation, 1990) both set in the same universe as this early story.

Art by Hisaki Yasuda

The next issues saw Octavia Butler's Hugo Award-winning "Speech Sounds" (mid-December 1983) and shortly after that her equally impressive "Bloodchild" (June 1984, a 1984 Nebula and 1985 Hugo winner); Robert Silverberg's monumental far-future adventure novella "Sailing to Byzantium" (February 1985, Nebula Award the same year), set in a world where everyone is a tourist and nothing is quite what it seems; rising star Kim Stanley Robinson's exciting novella "Green Mars" (1985), the tale of a band of adventurers determined to climb the tallest peak in the solar system, Olympus Mons (and a story which heralded his equally impressive Mars trilogy); and John Varley's terrifying tale of a homicidal artificial intelligence relentlessly tracking down all who learn of its existence, "Press Enter []" (May 1984), which shared the honour of a 1984 Nebula and 1985 Hugo Award with "Bloodchild." And in the mid-December issue of that year Isaac had a Christmas fantasy staring George and the imp Azazel, "Dashing Through the Snow." He would contribute a story to every mid-December issue until his death eight years later.

McCarthy was to hold the editor post for three years (breaking Ed Ferman's three-year stranglehold on the Best Professional Editor category by wresting away the Hugo in 1984), until Gardner Dozois was tapped for the post in January of 1986. Dozois was the first editor for the magazine to gain renown as a writer first, with back-to-back Nebula wins for his stories "The Peacemaker" and "Morning Child" the previous two years. Under his leadership **Asimov's**was to gradually emerge as the undisputed champion of short science fiction.

Art by Hisaki Yasuda

In the next five years Asimov's published an amazing array of original and award-winning fiction, including "Fermi and Frost" by Frederik Pohl (1986 Hugo); the delightfully original fantasy novella "Hatrack River" (1986) by Orson Scott Card, which introduced his famous character Alvin Maker, the seventh son of a seventh son in an ever-so-slightly different pioneer America; the 1986 Hugo-winner "Twenty-four Views of Mt. Fuji, by Hokusai" (July 1985) by Roger Zelazny; and "R&R" (April 1986) by Lucius Shepard, winner of the 1987 Nebula Award, a near-future tale of a Central American war where combat-enhancing drugs, telepathy, and mercenary soldiers combine in an explosive mix. It formed the opening chapter of his groundbreaking novel, Life During Wartime (Bantam, 1987). Other great pieces included Isaac Asimov's first new robot story in over a decade, "Robot Dreams" (mid-December 1986); "Rachel in Love" by Pat Murphy (1987 Nebula); "Flowers of Edo" by Bruce Sterling (May 1987); and the terrific adventure tale "Gilgamesh in the Outback" by Robert Silverberg (July 1986 issue, a 1987 Hugo Award winner).

Art by Bob Eggleton

In 1986 Asimov's began to experiment with serialized works. In January _William Gibson_published Count Zero, the sequel to his revolutionary Neuromancer, in three installments, and the mid-December issue saw the first third of a big new novel by Michael Swanwick, Vacuum Flowers. Set in a future where the asteroid belt swarms with teaming habitats, and Old Earth has been subjugated by an AI net that has integrated earthbound humanity into a malign group mind, Swanwick's novel followed the adventures of a young woman given an artificial personality that revolutionizes her life -- and who's already been killed twice before the novel opens. In November of 1987 we were presented with the first installment of Harlan Ellison's famously unproduced (and heretofore unpublished) masterwork, I Robot: The Movie. In December of 1990 Dozois gave the nod to chum Swanwick again, this time for his impressive novel Stations of the Tide, which won the 1991 Nebula Award for best novel.

While the serialized works were quite popular, many readers pointed out that they were usually available separately, and wondered just how many quality stories had been squeezed out to make room. For whatever reason, **Asimov's**has avoided serialized novels since.

Art by Bob Eggleton

1987 was a year of steady triumphs.Analog regular Orson Scott Card contributed the Hugo Award-winning "Eye for Eye" in March, a powerful and creepy tale of a young man forced to come to terms with a terrible heritage -- and an even more terrible ability to destroy everyone around him. In April it was "Rachel in Love" by Pat Murphy, a tale of genetic engineering, enhanced animal intellect, and the surprising capacity of love. It captured the hearts of readers, and the 1987 Nebula Award for best novelette. July of the same year saw Lawrence Watt-Evans' hilarious and eye-opening "Why I Left Harry's All Night Hamburgers," a story which catapulted Watt-Evans to fame by capturing the 1988 Hugo; August brought the Nebula Award-winning novella "The Blind Geometer" by regular Kim Stanley Robinson, and November the compelling fantasy "Uncle Dobbin's Parrot Fair" by Charles de Lint.

By the close of the 80s, Asimov's was simply the place to be for short science fiction and fantasy. "The Last of the Winnebagoes" by Connie Willis in the July 1988 issue (a 1989 Hugo and Nebula Award winner) and "The Scalehunter's Beautiful Daughter" by Lucius Shepard two months later (September 1988) perhaps bracketed the full spectrum of Asimov's at that point. The former is a thoughtful tale of

Art by Christos Achilleos

a woman who hits a dog with her car, set in a near-future middle America where ecological damage had played such havoc with animals that the SPCA wields unprecedented powers of arrest and persecution; the latter is an epic tale of love and magic set in a village nestled against the corpse of an ancient dragon. Other stories which I remember clearly from the period are the brilliant "Dori Bangs" by Bruce Sterling (1989), a daring 'what if' scenario in classic SF fashion... except this one postulates a meeting between two lonely counter-culture icons of the 80s, comic artist Dori Seda and rock critic and author Lester Bangs -- both dead at a tragically early age by 1989, but tenderly portrayed here in one of the most original alternate-world tales ever written. "Enter a Soldier. Later: Enter Another" by Robert Silverberg (June 1989, and winner of a Hugo the following year) proved that Silverberg still was the master of the form, and that no one brought him to you like Asimov's. "Boobs" by Suzy McKee Charnas (July 1989; 1990 Hugo Award) is a touching and humourous coming-of-age story of a young woman who finds her days as a wallflower are forever ended when puberty brings truly unexpected changes. And the final issue of that year, mid-December 1989, offered both a brand new robot story by the master himself ("Too Bad!" by Isaac Asimov) and a robot story starring Isaac by multiple award-winner Connie Willis, "Dilemma."

In 1988 Dozois was awarded his first Hugo for Professional Editor. It was a category he would come to thoroughly dominate over the next decade, winning every year except for 1994 (when he lost to The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction's Kristine Kathryn Rusch). Asimov's was finally to be recognized for what its fan has known for years -- as the premier source of quality short SF in the field.