From lepers to paranoia: The twisted history of the polka dot. (original) (raw)

Seeing Spots

From lepers to paranoia: The twisted history of the polka dot.

These days, polka dots are prized for their familiar cheerfulness. In an effort to lure budget-conscious consumers back to buying clothes, the fashion industry is hawking classic graphic patterns, from Breton sailor stripes to everything B&W to mixing multiple patterns. The idea is to appeal to a kind of old-fashioned frugality: Buying just one new striped boat-neck shirt or a dotted scarf can freshen up a closetful of old clothes.

Polka dots hearken to the 1950s, summing up the best of Mad Men-era America: optimistic, prosperous, ostensibly prim, but also dizzyingly energetic, the atomic age dissolving into particles before our eyes. Most superficially, polka dots suggest simplicity, fun, childhood (with a bent towards girlishness)—what could be a less complicated, less loaded pattern?

Yet the polka dot's roots are in more earthy stuff: animal pelts, warriors, and disease. At different moments, polka dots have hinted at sexuality, superhuman powers, torture, and paranoia. At one point they were part of a peasant dance craze that took both Europe and America by storm. Follow the bouncing dot in this slideshow—you'll be surprised where it leads.

CREDIT: "Polka Dots" by Flickr user Atiqah Aekman W. under Creative Commons 3.0.

Early in history, polka dots had a sinister quality. In medieval Europe, wearing dotted patterns on fabric was taboo. It wasn't easy to space the dots evenly without the help of machines, and irregularly spaced spots connoted more than anything the first visual manifestation of disease, particularly leprosy, syphilis, smallpox, bubonic plague, and measles. As scholar Steven Connor explains in a 2003 Textile article about spots, "Irregularly spotted fabrics are ominous not just because they are reminiscent of blemishes on the skin, but also because they are uncomfortable reminders of the ominous markings of other fabrics: the blood in the handkerchief that was a traditional sign of tuberculosis, and the 'spotting' … which may presage a miscarriage in early pregnancy. Desdemona's strawberry-spotted handkerchief, which leads to such disasters in Othello, joins together the associations of disease, deception, lust and corruption."

Ironically, spottedness was most reviled at its onset: One or two spots were judged much more unclean than a uniformly spotted surface. Leviticus 13 explains that a priest presented with an early stage leper must pronounce him unclean, particularly when "the appearance of the plague be deeper than the skin of his flesh." However, if "the leprosy cover all the skin of him that hath the plague from his head even to his feet … he [the priest] shall pronounce him clean that hath the plague: it is all turned white: he is clean." In other words, a full-blown case of leprosy signified a person on the threshold of death, someone whose suffering on earth might soon be transformed into a spotless transcendence in heaven. A single spot, on the other hand, suggested an incomplete (and therefore unnerving) transformation, one that had the potential to spread dangerously in all directions.

Granulomatous Orchitis, © 2008 CREDIT: WebPathology.com. All rights reserved.

Spots aren't the only outlaw graphic pattern of the Middle Ages—both spots and stripes marked social outcasts, although each pattern brought a different inflection. Connor explains the difference: "The point of the stripe is to mark an absolute and unconditional boundary between the included and the excluded. Those marked off with the stripe are outlandish, visibly set apart. But the horror and dread of the spot is that it invades, supervening upon and co-existing with a previously clear and unspotted countenance … . the striped one is a renegade; the spotted one is an apostate."

While spots suggested disease (either physical or moral) to the medieval eye, wearing stripes denoted anyone who was "barred" from the main action of polite society. As art historian Michel Pastoureau explains in his 1991 book, The Devil's Cloth: A History of Stripes, stripes marked "outcasts or reprobates, from the Jew and the heretic to the clown and the juggler, and including not only the leper, the hangman and the prostitute but also the disloyal knight of the Round Table, the madman of the Book of Psalms, and the character of Judas."

Dots and stripes played havoc with the medieval preference for reading any visual image in layers, moving from the bottom-most layer up through to the foreground. With stripes, dots, and checked patterns, "such a reading is no longer possible," writes Pastoureau. "There is not a level below and a level above, a background color and a figure color … the structure is the figure. Is that where the scandal originates?"

Medieval lepers rang bells to warn others of their supposedly contagious arrival.

In non-Western cultures, dots can convey magic, male potency, and the triumph of the hunt. Bushmen rock-art in southern Africa buzzes with different kinds of dots: "finger dots," "microdots," and "finger flecks," as ethnographers term them. All depict supernatural potency, but the more densely packed microdots show the concentrated, magical potency inside a shaman's body.

Both the Banda tribe of the Central African Republic and the Lega people of Democratic Republic of Congo traditionally daub adolescent boys with white dots for male-initiation rites. The Lega rite is particularly dot-obsessed: The rite calls for the young man, adorned in dots, to knock incessantly at a specially constructed polka-dotted door (keibi) as a test of his piety and persistence. Eventually he's admitted and presents gifts to his father in thanks. All the participants, their skins also speckled with white dots, pay homage to the keibi, whose dots represent the leopard, which frightens goats and other animals but doesn't faze the young hunter. The initiation ends in a group dance, where the adult "herd of elephants" (idumbu) admits the "little elephant" (kalupepe), together making a whirling, energetic blur of dots.

Dots in a specific formation called çintamani crop up frequently in Buddhist, Hindu, and Islamic design and practically served as the logo of the Ottoman empire in the late-16th to early-17th centuries. Often called the "lips and balls" pattern, çintamani consists of three dots arranged in a triangle, connected by wavy, lip-shaped lines. The çintamani dots represent a sacred wish-fulfilling pearl, a gift from the Buddha to king Lha Thothori Nyantsen of fifth-century Tibet; the wavy lines usually suggest tiger stripes.

CREDIT: Ceremonial caftan with long sleeves associated with Murat IV (1623-40), satin with three circle pattern and stripes made of gold stitches, 17th century, courtesy of the Turkish Cultural Foundation.

As clothes and accessories began to denote not just class and occupation but style and self expression, the dot took on new roles. Case in point: From the 1590s to the 1720s, European ladies took to a fashion called "patching."

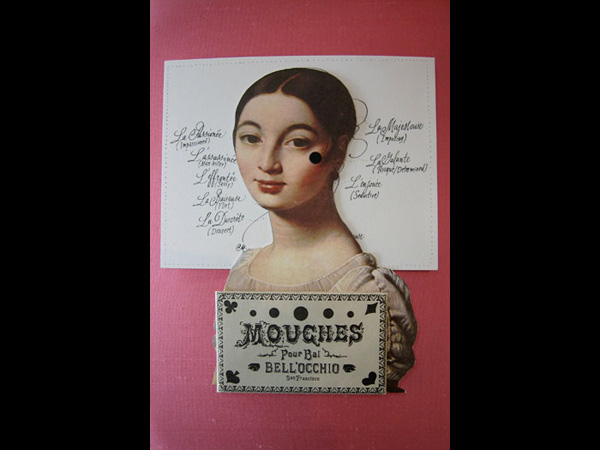

Sometimes referred to as a "moucheron," French for "little fly," patching involved strategically sticking a dot of black fabric to the face, either to cover a blemish or simply to offset, and therefore enhance, the beauty of otherwise flawless skin. Patches could imitate real moles, gaming the 17th- and 18th-century craze for fortune-telling by "reading" the location of moles on one's face. Patches came in handy for more practical dissemblances, too. In a diary entry from 1668, Samuel Pepys observes the Lady Castlemayne frantically licking and slapping a black patch to her face in full view in her theater box. "I suppose she [felt] a pimple rising there," Pepys notes dryly.

Ever-ready to prime their outrage at popular ostentations, the Puritans happily took aim at the patching phenomenon. In the 1630 poem "The Vicious Courtier," Nathaniel Richards rails against female vanity, focusing on the foul black patch: "The painted outside of a tempting Face,/ Spotted with Hell, stands sequestred from Grace." A patch-addicted lady—relative of gentleman-scientist Kenneth Digby in the 17th century—never dared to show herself in public without a multitude of patches shaped like stars or crescents all over her face and neck. When she became pregnant, Digby warned her to drop her patching, lest sympathetic vibes between mother and unborn baby similarly "mark" the child. She refused, and her telling vanity resulted in a ghastly dark blotch, a concentration of spotted patches, on the child's forehead. After a plague outbreak in London in 1665, patching became associated with disease and all the virulent ways it spread, like prostitution.

CREDIT: Mouche Packets by Bell'occhio.

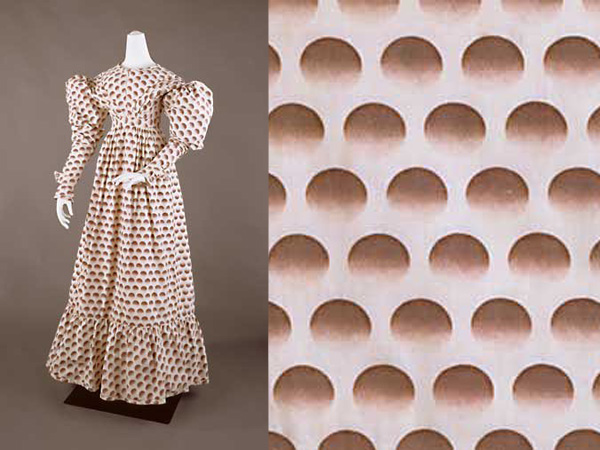

Late Rococo aristocracy in the mid-18th century abounded in elaborate floral brocaded silks, but the French Revolution swept the fashion plate clean, clearing the way for Neo-Classical styles which favored paler colors and small neat patterns, often against a crisp white backdrop. Regularly spaced on an unseen latticework, often machine-produced, polka dots from this era looked remarkably fresh and modern, the "clean" product of culture versus nature and the perfect symbol of a rising manufacturing age.

Roller-printed cotton polka-dot dress, 1830, courtesy the CREDIT: Cora Ginsburg Gallery, New York City.

Dotted-fabric patterns went by various names in mid-19th-century Europe. Dotted-Swiss referred to raised dots on transparent tulle. The French quinconce described the diagonal arrangement of dots seen on the 5-side of dice. The large coin-sized dots on fabric, called Thalertupfen in German, got their name from Thaler, the currency of German-speaking Europe until the late 1800s and the term from which the English word dollar descends.

The English term polka dots stems from an extended craze for polka music and dancing that swept east to west from Europe between the 1840s and 1860s. Legend has it a Hungarian dancing professor named Neruda discovered a peasant half-step dance in Bohemia that made everyone's toes feel a tad lighter. Named variously for the Czech words p?lka ("little-step"), pole ("field"), and Polka ("Polish woman," female counterpart of Polák), the connection between the pattern and the dance is murky; possibly the spotted pattern evoked the lively half-step of the dance. In any event, the polka ripped through the Bohemian fields to Prague, ignited the ladies of Paris by 1840, hopped the Channel to London by 1844, then set America ablaze. James Polk enjoyed a dotty, if accidental, glow of popularity during his (successful) presidential bid that same year. In 1845, the polka was danced in Calcutta at a ball given by the governor-general in honor of Queen Victoria.*

Correction, Aug. 12, 2010: This slide originally stated that Queen Victoria danced the polka at the celebration. The author did not realize Queen Victoria did not visit India. (Return to the corrected sentence.)

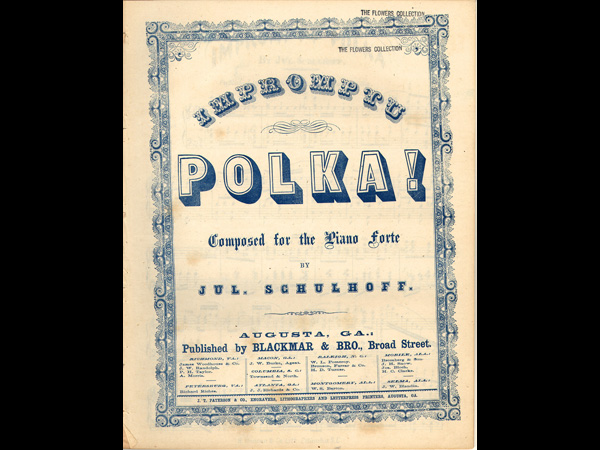

"Impromptu Polka" by Julius Schulhoff, 1864, from the CREDIT: Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library.

Polka's popularity was eye-popping. The Oxford Grove Music relates the remarks of the Paris correspondent for the London Times during this period: "Politics is for the moment suspended in public regard by the new and all-absorbing pursuit, the Polka." In 1844, the year the polka arrived in London, Punch lampooned the constant chatter about the dance in society circles: "'Can you dance the Polka? Do you like the Polka? Polka – Polka – Polka – Polka'– it is enough to drive me mad." That same year, the Brighton Gazette reports an anecdote about a fashionable lady hassling the famed polka dance-master Perrot for private lessons. Not wishing to offend the influential dame with an outright refusal, Perrot gave his price as £5 per lesson, "thinking that she would never dream of paying so enormous a sum; in that he was disappointed. 'The price is nothing,' said the lady. 'Give me the lesson.' Perrot did so; and in less than a week he had a great number of pupils at the same rate."

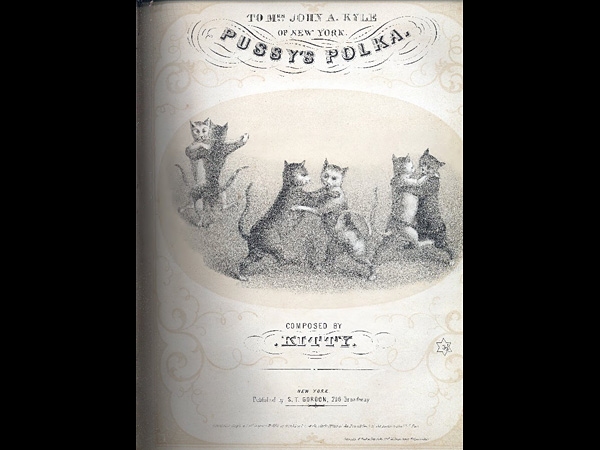

Sheet-music composers cranked out polkas in bewildering variety. "The Aurora Borealis Polka," "Happy Family Polka," "General Grant Polka," "Hiawatha's Bridal Polka," "Pussy's Polka" ("Composed by Kitty"), "Katy-did Polka," "Thunder and Lightning Polka," "Barnum's Baby Show Polka": Every occasion, every social group, every weather pattern, every passing mood was stamped with its own perfect polka.

CREDIT: Pussy's Polka by Kitty, from the 19th-Century American Sheet Music Collection, Music Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Marketers hawked every product they could as polka-themed: polka pudding (a boozy confection of orange-water-flavored cream, drizzled with sherry polka sauce), polka curtains, polka gauze, polka hats, shoes, and vests, many bedizened with a kicky pattern Godey's Lady Book_—the Good Housekeeping of its day—dubbed the polka dot. The polka-product craze flamed out, but the term "polka dots" for the dotted pattern stuck.

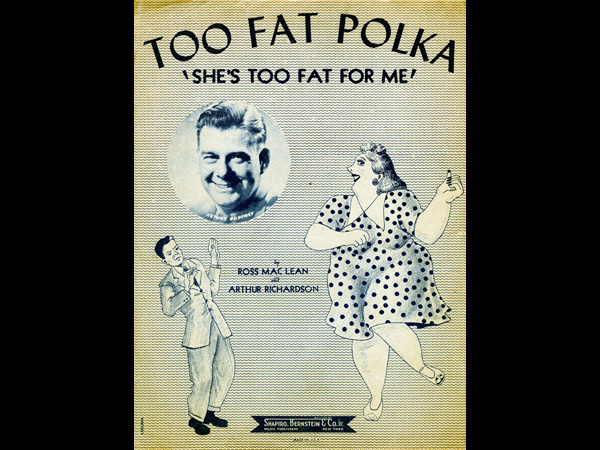

Like the spores of a stubborn weed, polka survived both dry spells and detractors to flower anew. An expression of regional pride by Central European immigrants, polka music roared back into style in WWII-era America with Jaromír Vejvoda's "Mod?anská Polka," known in America as the "Beer Barrel Polka."_ "America's Polka King" Frankie Yankovic (no relation to Weird Al) set jolly beer-bellies swinging across the Midwest in the 1960s. In the 1980s, polka music popped up yet again, this time in sub-genres ranging from Chicago honky-style to Norteño Mexican to chicken-scratch Pima Indian polka. Everywhere across the States, little dots kept glowing.

"Too Fat Polka" by Ross Mac Lean and Arthur Richardson, 1947, from the CREDIT: Templeton Digital Sheet Music Collection, Mississippi State University Libraries.

Polka dots took a subversive turn in early 20th-century America. Clean and utterly simple in their machine-printed version, the pattern exuded a lively wholesomeness appropriate for children. It became especially popular on bedsheets, bassinets, and nightgowns. Yet the tiniest of tweaks—packing the dots more tightly together, say, or allowing them to jostle and overlap—could produce a woozy sense of acceleration, even an exhilarating disorientation. These two qualities combined—child-friendliness with intoxication—tinged the polka dot with a distinctly female aura, mother and sexpot rolled into one round body.

Frank Sinatra's first breakout hit in 1940, "Polka Dots and Moonbeams," gives a whiff of the thrilling, romantic, and frankly off-the-wall feelings polka dots could convey. Two lovers first meet at a country dance; when sparks fly, they take a giddy polka-dot's shape, a Portrait of Dotty Love (With Hearth-Warmed Bulldog):The music started and was I the perplexed one

I held my breath and said 'May I have the next one?'

In my frightened arms, polka dots and moonbeams

Sparkled on a pug-nosed dream

By 1936, polka dots were sufficiently big business for the fashion industry that shoe designer Miss Mary Bendalari sued Irving Fox of the National Retail Dry Goods Association for copyright infringement of her strap-sandal designs, as well as polka-dot and daisy patterns. "Wearing an 'original' dress of dark blue-and-white striped chiffon over blue, with a belt decoration of red and blue stars and a corsage cluster of small 'gold stars' in honor of the 'friends of design copyright,' " which she dubbed the "Constitutional Inspiration" and dedicated to Mr. Fox, Miss Bendalari defended designers' right to accrue coin based on designs featuring unique variants on the polka dot. "How can you copyright a polka dot or a daisy, or claim as original arrangement of polka dots or any adaptation of the daisy motif?" demanded Fox, to which Bendalari spunkily (if illogically) retorted, "There is only one principle here, no matter how you smother it with polka dots. ... We base our demand for copyright protection on the Constitution, in which our right to it is specifically provided." Bendalari ultimately lost the suit, but her plucky defense (and fetchingly patriotic ensemble) epitomized the polka dot as the energetic motif nouveau for modern women.

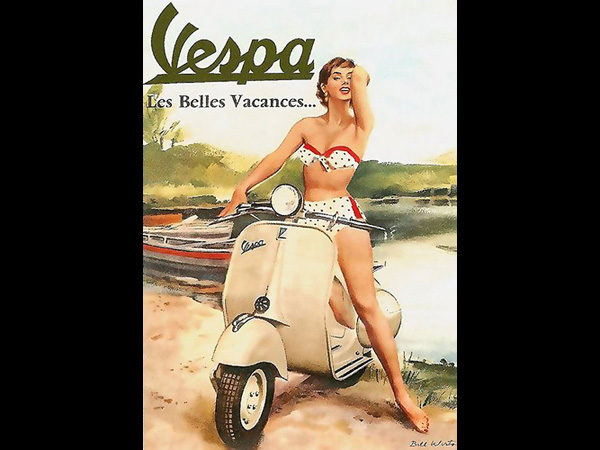

Vespa advertisement, via Flickr user CREDIT: x-ray delta one under Creative Commons 3.0.

The year 1940 exploded with a beguiling proliferation of dots of every shape, size, and arrangement. "You can sign your fashion life away on the polka-dotted line, and you'll never regret it this season," the Los Angeles Times remarked in spring 1940. Three years later, the Washington Post elevated the polka dot as the pattern of democratic values in wartime: "What we mean by a print with social significance is one that most people can wear most of the time. The whole family of polka dots falls into that category even if they don't spell 'Remember Pearl Harbor' in code. The full-grown variety in particular makes a clean-cut monotone pattern that is neither dizzy nor monotonous. It is as good in a closeup as it is in perspective and manages to be in pleasing proportion to all kinds of figures. It requires no more than a casual acquaintance with the cleaner." Clean, friendly, upbeat, durable, and universally pleasing, polka dots signaled the triumphant pulse of midcentury America.

"She's a WOW. Woman Ordnance Worker," by Adolph Treidler for the U.S. Army Ordinance Corps, 1942, via Flickr user CREDIT: michal_hadassah under Creative Commons 3.0.

The prosperous post-WWII years brimmed with polka dots, but the cheerful pattern eventually curdled back into something darker, an insistently optimistic and guileless face papering over the troubled underworld of the atomic age.

Filmmaker Billy Wilder distorted the 1960 hit "Itsy Bitsy Teeny Weeny Yellow Polka Dot Bikini" into a torture device in his 1961 movie, One, Two, Three. An American Coca-Cola executive in recently walled-off West Berlin welcomes his boss's daughter to town, where she promptly and calamitously marries a GDR Communist zealot. With a surprise Berlin visit from the boss looming, the Coke exec wastes no time in branding the young lover as a Yankee spy and siccing the Stasi on him. They wear down his resistance with screechy, repeated record-playing of "Itsy Bitsy Teeny Weeny Yellow Polka Dot Bikini", relentless American capitalism and dots boring triumphantly into the skull.

1962 saw the introduction of Marvel Comics character Polka Dot Man, whose belt issued a stream of nefarious spots on command that morphed into useful superhero accoutrements, like flying saucers that could be used as getaway cars. Television pixels? Polio germs? Radioactive ions? Secret Communist leanings? Midcentury America was riddled with invisible dots, infiltrating society for good or evil—ambivalent spores embodied in the seemingly innocuous polka dot.

Album cover, CREDIT: The Very Best of Brian Hyland.

"Burn Wall Street. Wall Street men must become farmers and fishermen. ... Obliterate the men of Wall Street with polka dots on their naked bodies," wrote artist Yayoi Kusama, Japanese performance artist and past master of the polka dot.

Covering every surface of Kusama's work since her heyday in the 1960s, her polka-dot energy blares forth without boundaries, upsettingly loud. Kusama favors dots in her art as an expression of cosmic pixelation, an almost vicious democracy in which every object, person, and atmospheric vibe boils down to the particulate: "Our earth is only one polka dot among millions of others," she writes. "When Kusama paints your body with polka dots you become part of the unity of the universe." Imagining today's flying 0s and 1s of data surging through fiber-optic cables girdling the globe, a futuristic view of the world as dots feels uncannily apt.

By 2006, having voluntarily committed herself to a mental institution (and modified her anti-capitalist stance to the point of designing cell phones, T-shirts, and other dotty tchotchkes), Kusama's love for dots softened in tone if not in ardency. "[Dots] scatter proliferating love in the universe and raise my mind to the height of the sky," she writes. "This mysterious dots obsession."

Photograph of a Yayoi Kusama art installation by Yoshikazu Tsuno/Getty Images.

Click here to read a slide-show essay on the history of polka dots.

_Special thanks to Leigh Wishner of Cora Ginsburg Gallery, NYC; Jen Colman of the Cooper-Hewitt Design Museum; and Professor Steven Connor of Birkbeck College, London.