Jean-Baptiste Charles Bouvet de Lozier (original) (raw)

|

Jean-Baptiste Charles Bouvet de Lozier was born in 1705. Orphaned at the age of 7, upon receiving his education in Paris he was sent to work in the shipyards at St. Malo. He studied navigation and received the rank of lieutenant in the Compagnie des Indes in 1731. With an insatiable desire to explore the southern seas, he petitioned his employers in 1733 with a plan of exploration. He asked for two ships consisting of a frigate and a larger trading vessel. For this, he promised to search the southern seas for land that could accommodate French trading vessels on route to the Far East. With a touch of arrogance, Bouvet adamantly expressed his desires to discover new land, in the name of France, and "If the Company accepts my plans, I insist on being given complete authority and made Governor of whatever I discover. A New Europe offers itself to whomsoever dares to discover it!" Some three years later, his wish was granted. On July 19, 1738 the AIGLE and MARIE left the port of Lorient on a course for Santa Catarina Island off the coast of Brazil. Bouvet landed in early October, made repairs, resupplied the vessel and sailed southeast one month later. Although poorly equipped for the cold weather to follow, the ships crossed the 44th parallel on December 10th. Shrouded in fog, this was the area placed on early maps where Bouvet was to find Terres Inconnues. |

|---|

It wasn't until December 15th that the fog lifted and, unfortunately, all that was discovered was a large iceberg! The next day they had their first penguin encounter with Bouvet describing them as "amphibious creatures that look like large ducks, but have fins instead of wings". Continuing south, by the end of December they were nearly 1600 miles from inhabited land. Icebergs were increasingly present causing much fear in the crew..."In effect [they] are floating rocks which are more to be feared than land. If we hit one we will be lost...". On January 1, 1739, at 3:00 PM they spotted "a very high land, covered with snow, which appeared through the mist". It really was a miracle as Bouvet stumbled upon the only land within 20 degrees west and 90 degrees east! Bouvet believed it to be a promontory of the Antarctic mainland and promptly named it the "Cape of Circumcision". For twelve days Bouvet tried to land on the island but the dense fog suggested he continue to wait. Food staples became depleted and the crew fell sick with scurvy. With his crew devastated, Bouvet surrendered to the weather and headed east, following the 52nd parallel while skirting the ice floes. The crew had spotted a significant number of penguins and seals suggesting Terres Australes lay to the south. On January 25, Bouvet's seriously ill crew turned north for the Cape of Good Hope and anchored there on February 24.

It took three long months for the return voyage to France, reaching the port of Lorient on June 24. Five days later Bouvet drafted a letter which was sent to his directors suggesting his intense disappointment:

"I am sorry to inform you that the Terres Australes are much further from the Pole than hitherto believed, and completely unsuitable as a staging post for vessels en route to the Indies. We have sailed 1200-1500 leagues (3600-4500 miles) in unknown waters, and for seventy days encountered almost continuous fog. We were forty days among the icebergs and we had hail and snow almost every day. The cold was severe for men accustomed to a warmer climate. They were badly clothed and had no means of drying their bedding. Many suffered from chilblains but they had to keep working. I saw sailors crying with cold as they hauled in the sounding line. To alleviate the men's discomfort I distributed blankets, hats, shoes, old clothes...and I opened two kegs of brandy to issue to the crew. The dangers were as great as the discomforts. For more than two months we had been in uncharted waters. We had very little daylight and there were few times when we weren't encountering some kind or risk...It was not the officers and crew who failed in their mission, but rather the mission that failed them".

Although hugely disappointed, Bouvet was admired as an explorer with his name being added to the "Compagnie's" roll of honor. A number of navigational errors were committed by Bouvet during his exploration casting doubt on the very existence of his Cape of Circumcision. Captains James Cook and James Clark Ross both tried to find it, without success, as it had been incorrectly charted. Incredibly, it was 1808 before again being sighted, this time by the English whalers James Lindsay of the SNOW SWAN and Thomas Hopper of the OTTER. As with Bouvet, they were unable to approach the island. The first landing did not come until 1822 when American Benjamin Morrell forged on shore. In honor of the discoverer, he renamed it Bouvet's Island. Three years later an Englishman, Norris, chose to rename it Liverpool Island but on December 1, 1929, a Norwegian expedition claimed the 22 square mile island for Norway and once again credited its original discoverer by naming it Bouvet Island.

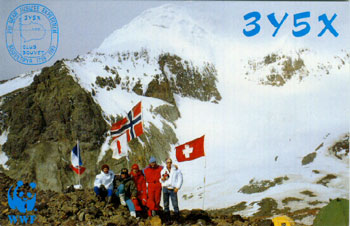

Ham Radio QSL Card: My Confirmed 2-Way Radio Contact With Bouvetøya

RECOMMENDED READING:

Antarctica; the Extraordinary History of Man's Conquest of the Frozen Continent, by Reader's Digest.

Antarctica, the Last Continent, by Ian Cameron.

Antarctic Conquest, the Great Explorers in Their Own Words, by Walker Chapman.

The White Continent, by Thomas R. Henry.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Antarctica; the Extraordinary History of Man's Conquest of the Frozen Continent, published by Reader's Digest, second edition.

|

|

|---|