Mars: Everything you need to know about the Red Planet (original) (raw)

Mars is the fourth planet from the sun and is also known as the Red Planet. (Image credit: Future/Tobias Roetsch)

Mars is the fourth planet from the sun and has a distinct rusty red appearance and two unusual moons.

The Red Planet is a cold, desert world within our solar system. It has a very thin atmosphere, but the dusty, lifeless (as far as we know it) planet is far from dull.

Phenomenal dust storms can grow so large they engulf the entire planet, temperatures can get so cold that carbon dioxide in the atmosphere condenses directly into snow or frost, and marsquakes — a Mars version of an earthquake — regularly shake things up. Therefore, it is no surprise that this little red rock continues to intrigue scientists and is one of the most explored bodies in the solar system, according to NASA Science.

Related: How long does it take to get to Mars?

Befitting the Red Planet's bloody color, the Romans named it after their god of war. In truth, the Romans copied the ancient Greeks, who also named the planet after their god of war, Ares.

Other civilizations also typically gave the planet names based on its color — for example, the Egyptians named it "Her Desher," meaning "the red one," while ancient Chinese astronomers dubbed it "the fire star."

Why is Mars called the Red Planet?

The bright rust color Mars is known for is due to iron-rich minerals in its regolith — the loose dust and rock covering its surface. Earth's soil is a kind of regolith, too, albeit one loaded with organic content. According to NASA, the iron minerals oxidize, or rust, causing the soil to look red.

Mars Q&A with an Expert

We asked David C. Agle media relations at NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California which handles missions on the Martian surface such as the Perseverance Rover some questions about the Red Planet.

David Agle is a writer, producer and media relations at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena.

What type of planet is Mars?

Mars is a terrestrial, or rocky, planet.

Why is Mars known as the "Red Planet"?

Mars is known as the "Red Planet" because it appears faintly reddish/orange when viewed in the night sky. This reddish color comes from the abundance of iron minerals and dust on the Martian surface.

How is Mars different from Earth?

Mars is further from the sun and smaller than Earth, and at least as far as we know, does not appear to be habitable by life.

What do we know about Mars' past and was it ever like our planet?

We've learned a lot about Mars from the past 30 years of lander, rover, and orbiter missions. We have confirmed the existence of past water on the Martian surface, that Mars was once a habitable planet, and that it once had a thicker atmosphere than it does today.

What have we learned about Mars over the past decade thanks to missions like Curiosity, InSight, and Perseverance?

Curiosity and Perseverance are studying ancient habitable environments exposed on the surface of Mars, and both missions have found evidence that the basic ingredients that life needs to exist were present at the surface or near-subsurface on Mars billions of years ago. InSight offered us an unprecedented view into the interior of Mars.

What is the biggest unanswered question about Mars?

Although we know now that Mars was a habitable planet in the past, the biggest unanswered question about Mars is whether it actually hosted life.

Mars' surface

The planet's cold, thin atmosphere means liquid water likely cannot exist on the Martian surface for any appreciable length of time. Features called recurring slope lineae may have spurts of briny water flowing on the surface, but this evidence is disputed; some scientists argue the hydrogen spotted from orbit in this region may instead indicate briny salts. This means that although this desert planet is just half the diameter of Earth, it has the same amount of dry land.

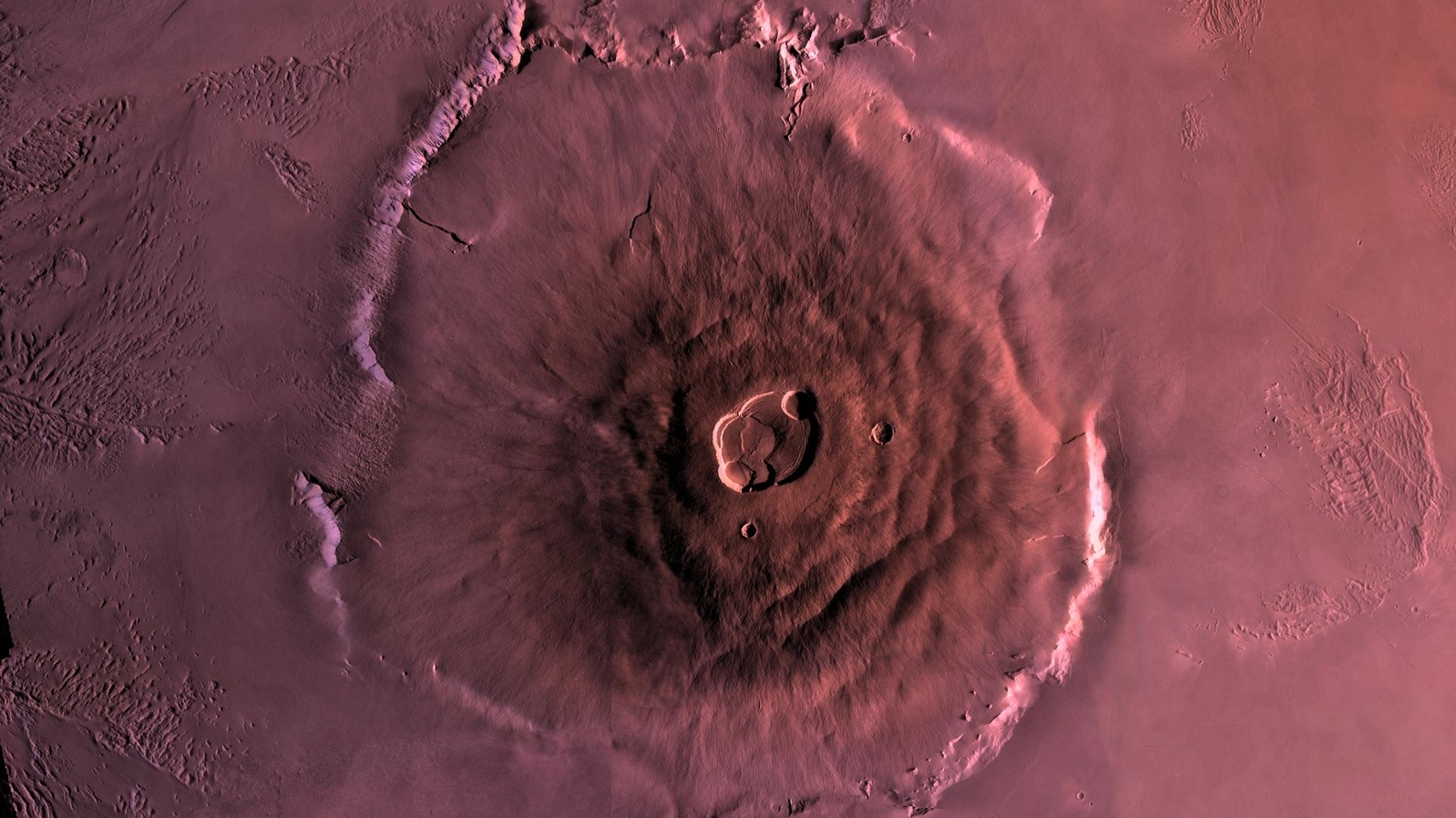

The Red Planet is home to both the highest mountain and the deepest, longest valley in the solar system. Olympus Mons is roughly 17 miles (27 kilometers) high, about three times as tall as Mount Everest, while the Valles Marineris system of valleys — named after the Mariner 9 probe that discovered it in 1971 — reaches as deep as 6 miles (10 km) and runs east-west for roughly 2,500 miles (4,000 km), about one-fifth of the distance around Mars and close to the width of Australia.

Scientists think the Valles Marineris formed mostly by rifting of the crust as it got stretched. Individual canyons within the system are as much as 60 miles (100 km) wide. The canyons merge in the central part of the Valles Marineris in a region as much as 370 miles (600 km) wide. Large channels emerging from the ends of some canyons and layered sediments within suggest that the canyons might once have been filled with liquid water.

Mars also has the largest volcanoes in the solar system, Olympus Mons being one of them. The massive volcano, which is about 370 miles (600 km) in diameter, is wide enough to cover the state of New Mexico. Olympus Mons is a shield volcano, with slopes that rise gradually like those of Hawaiian volcanoes, and was created by eruptions of lava that flowed for long distances before solidifying. Mars also has many other kinds of volcanic landforms, from small, steep-sided cones to enormous plains coated in hardened lava. Some minor eruptions might still occur on the planet today.

Related: Space volcanoes: Origins, variants and eruptions

Olympus Mons is the largest known volcano in the solar system. This digital mosaic image of the volcano was captured by NASA's Viking 1 Orbiter. (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/USGS)

Channels, valleys and gullies are found all over Mars, and suggest that liquid water might have flowed across the planet's surface in recent times. Some channels can be 60 miles (100 km) wide and 1,200 miles (2,000 km) long. Water may still lie in cracks and pores in underground rock. A study by scientists in 2018 suggested that salty water below the Martian surface could hold a considerable amount of oxygen, which could support microbial life. However, the amount of oxygen depends on temperature and pressure; temperature changes on Mars from time to time as the tilt of its rotation axis shifts.

Many regions of Mars are flat, low-lying plains. The lowest of the northern plains are among the flattest, smoothest places in the solar system, potentially created by water that once flowed across the Martian surface. The northern hemisphere mostly lies at a lower elevation than the southern hemisphere, suggesting the crust may be thinner in the north than in the south. This difference between the north and south might be due to a very large impact shortly after the birth of Mars.

The number of craters on Mars varies dramatically from place to place, depending on how old the surface is. Much of the surface of the southern hemisphere is extremely old, and so has many craters — including the planet's largest, 1,400-mile-wide (2,300 km) Hellas Planitia — while that of northern hemisphere is younger and so has fewer craters. Some volcanoes also have just a few craters, which suggests they erupted recently, with the resulting lava covering up any old craters. Some craters have unusual-looking deposits of debris around them resembling solidified mudflows, potentially indicating that the impactor hit underground water or ice.

In 2018, the European Space Agency's Mars Express spacecraft detected what could be a slurry of water and grains underneath icy Planum Australe. (Some reports describe it as a "lake," but it's unclear how much regolith is inside the water.) This body of water is said to be about 12.4 miles (20 km) across. Its underground location is reminiscent of similar underground lakes in Antarctica, which have been found to host microbes. Late in the year, Mars Express also spied a huge, icy zone in the Red Planet's Korolev Crater.

Mars' moons

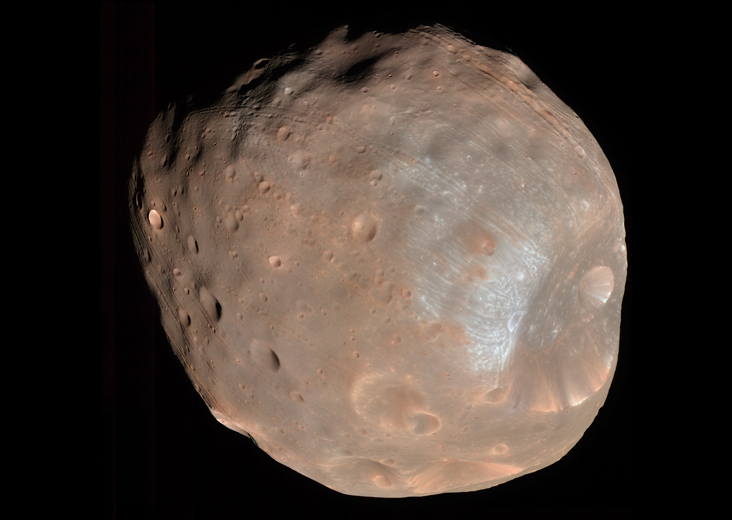

The two moons of Mars, Phobos and Deimos, were discovered by American astronomer Asaph Hall over the course of a week in 1877. Hall had almost given up his search for a moon of Mars, but his wife, Angelina, urged him on. He discovered Deimos the next night, and Phobos six days after that. He named the moons after the sons of the Greek war god Ares — Phobos means "fear," while Deimos means "rout."

Image of Phobos captured by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (Image credit: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona)

Both Phobos and Deimos are apparently made of carbon-rich rock mixed with ice and are covered in dust and loose rocks. They are tiny next to Earth's moon, and are irregularly shaped, since they lack enough gravity to pull themselves into a more circular form. The widest Phobos gets is about 17 miles (27 km), and the widest Deimos gets is roughly 9 miles (15 km). (Earth's moon is 2,159 miles, or 3,475 km, wide.)

Both Mars moons are pockmarked with craters from meteor impacts. The surface of Phobos also possesses an intricate pattern of grooves, which may be cracks that formed after the impact created the moon's largest crater — a hole about 6 miles (10 km) wide, or nearly half the width of Phobos. The two Martian satellites always show the same face to their parent planet, just as our moon does to Earth.

Image of Deimos captured by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona)

It remains uncertain how Phobos and Deimos were born. They may be former asteroids that were captured by Mars' gravitational pull, or they may have formed in orbit around Mars at roughly the same time the planet came into existence. Ultraviolet light reflected from Phobos provides strong evidence that the moon is a captured asteroid, according to astronomers at the University of Padova in Italy.

Phobos is gradually spiraling toward Mars, drawing about 6 feet (1.8 meters) closer to the Red Planet each century. Within 50 million years, Phobos will either smash into Mars or break up and form a ring of debris around the planet.

Mars quick facts: Size, composition and structure

Mars is 4,220 miles (6,791 km) in diameter — far smaller than Earth, which is 7,926 miles (12,756 km) wide. The Red Planet is about 10% as massive as our home world, with a gravitational pull 38% as strong. (A 100-pound person here on Earth would weigh just 38 pounds on Mars, but their mass would be the same on both planets.)

Atmospheric composition (by volume)

According to NASA, the atmosphere of Mars is 95.32% carbon dioxide, 2.7% nitrogen, 1.6% argon, 0.13% oxygen and 0.08% carbon monoxide, with minor amounts of water, nitrogen oxide, neon, hydrogen-deuterium-oxygen, krypton and xenon.

Magnetic field

Mars lost its global magnetic field about 4 billion years ago, leading to the stripping of much of its atmosphere by the solar wind. But there are regions of the planet's crust today that can be at least 10 times more strongly magnetized than anything measured on Earth, which suggests those regions are remnants of an ancient global magnetic field.

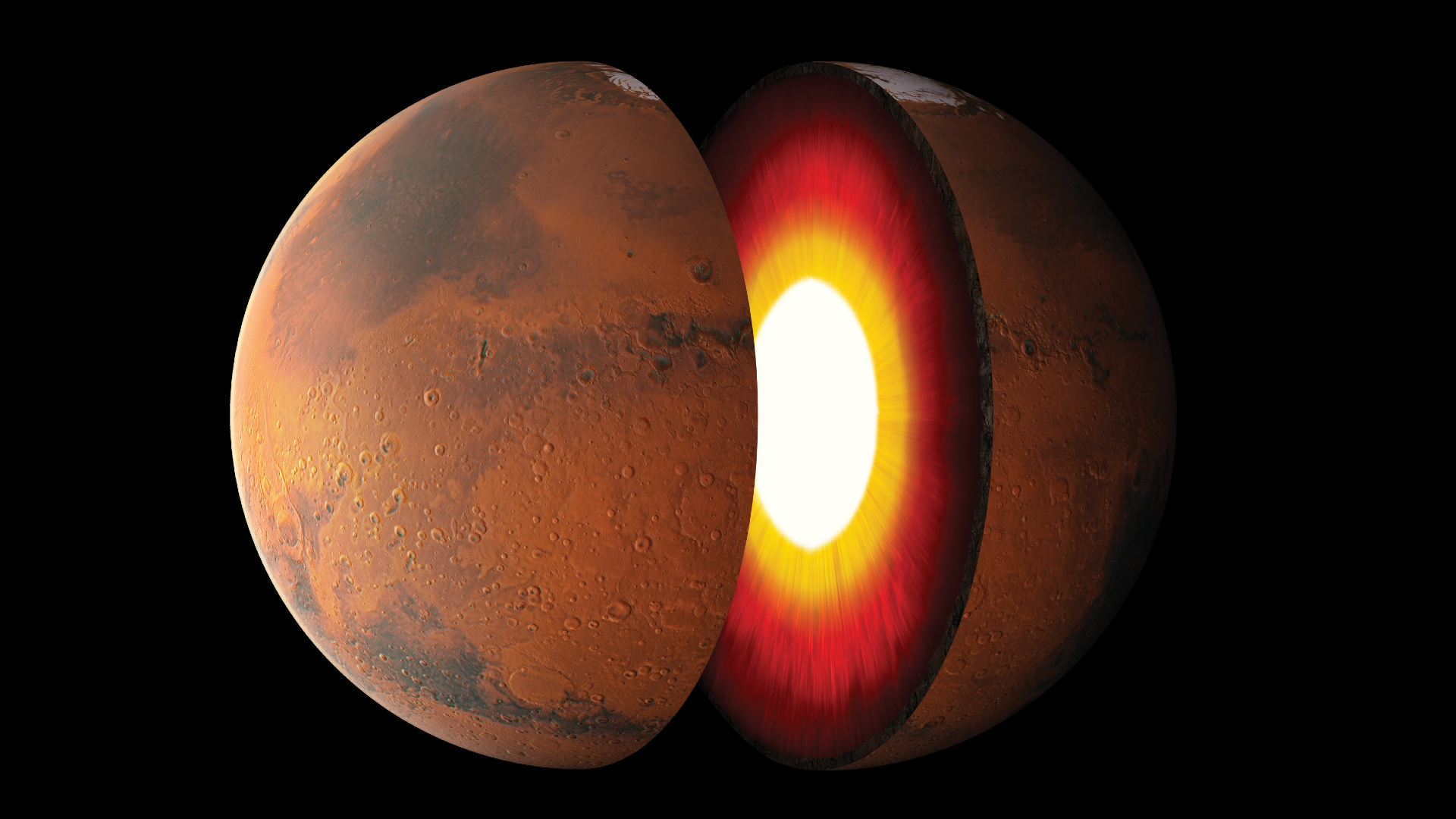

Internal structure

NASA's InSight lander has been probing the Martian interior since touching down near the planet's equator in November 2018. InSight measures and characterizes marsquakes, and mission team members are tracking wobbles in Mars' tilt over time by precisely tracking the lander's position on the planet's surface.

These data have revealed key insights about Mars' internal structure. For example, InSight team members recently estimated that the planet's core is 1,110 to 1,300 miles (1,780 to 2,080 km) wide. InSight's observations also suggest that Mars' crust is 14 to 45 miles (24 and 72 km) thick, on average, with the mantle making up the rest of the planet's (non-atmospheric) volume.

For comparison, Earth's core is about 4,400 miles (7,100 km) wide — bigger than Mars itself — and its mantle is roughly 1,800 miles (2,900 km) thick. Earth has two kinds of crust, continental and oceanic, whose average thicknesses are about 25 miles (40 km) and 5 miles (8 km), respectively.

Chemical composition

Mars likely has a solid core composed of iron, nickel and sulfur. The mantle of Mars is probably similar to Earth's in that it is composed mostly of peridotite, which is made up primarily of silicon, oxygen, iron and magnesium. The crust is probably largely made of the volcanic rock basalt, which is also common in the crusts of the Earth and the moon, although some crustal rocks, especially in the northern hemisphere, may be a form of andesite, a volcanic rock that contains more silica than basalt does.

Mars' polar caps

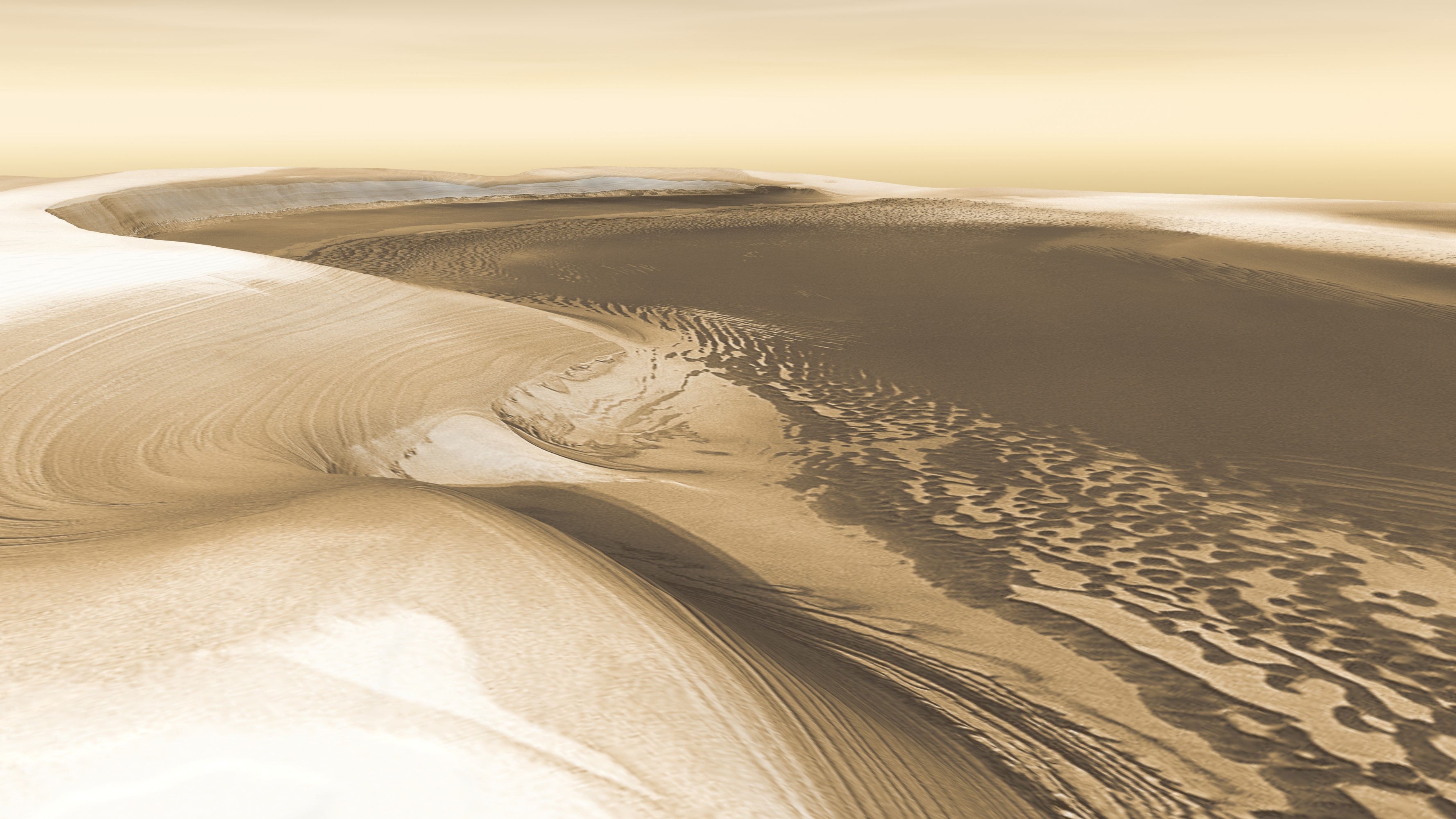

Vast deposits of what appear to be finely layered stacks of water ice and dust extend from the poles to latitudes of about 80 degrees in both Martian hemispheres. These were probably deposited by the atmosphere over long spans of time. On top of much of these layered deposits in both hemispheres are caps of water ice that remain frozen year-round.

Additional seasonal caps of frost appear in the wintertime. These are made of solid carbon dioxide, also known as "dry ice," which has condensed from carbon dioxide gas in the atmosphere. (Mars' think air is about 95% carbon dioxide by volume.) In the deepest part of the winter, this frost can extend from the poles to latitudes as low as 45 degrees, or halfway to the equator. The dry ice layer appears to have a fluffy texture, like freshly fallen snow, according to a report in the Journal of Geophysical Research-Planets.

Mars' climate

Ice and dust build the Martian polar caps. (Image credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk)

Mars is much colder than Earth, in large part due to its greater distance from the sun. The average temperature is about minus 80 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 60 degrees Celsius), although it can vary from minus 195 F (minus 125 C) near the poles during the winter to as much as 70 F (20 C) at midday near the equator.

The carbon-dioxide-rich atmosphere of Mars is also about 100 times less dense than Earth's on average, but it is nevertheless thick enough to support weather, clouds and winds. The density of the atmosphere varies seasonally, as winter forces carbon dioxide to freeze out of the Martian air. In the ancient past, the atmosphere was likely significantly thicker and able to support water flowing on the planet's surface. Over time, lighter molecules in the Martian atmosphere escaped under pressure from the solar wind, which affected the atmosphere because Mars does not have a global magnetic field. This process is being studied today by NASA's MAVEN (Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution) mission.

NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter found the first definitive detections of carbon-dioxide snow clouds, making Mars the only body in the solar system known to host such unusual winter weather. The Red Planet also causes water-ice snow to fall from the clouds.

The dust storms on Mars are the largest in the solar system, capable of blanketing the entire Red Planet and lasting for months. One theory as to why dust storms can grow so big on Mars is because the airborne dust particles absorb sunlight, warming the Martian atmosphere in their vicinity. Warm pockets of air then flow toward colder regions, generating winds. Strong winds lift more dust off the ground, which, in turn, heats the atmosphere, raising more wind and kicking up more dust.

These dust storms can pose serious risks to robots on the Martian surface. For example, NASA's Opportunity Mars rover died after being engulfed in a giant 2018 storm, which blocked sunlight from reaching the robot's solar panels for weeks at a time.

NASA's Curiosity Mars rover imaged these drifting clouds on May 17, 2019, the 2,410th Martian day, or sol, of the mission, using its black-and-white navigation cameras. (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Mars' orbit around the sun

Mars lies farther from the sun than Earth does, so the Red Planet has a longer year — 687 days compared to 365 for our home world. The two planets have similar day lengths, however; it takes about 24 hours and 40 minutes for Mars to complete one rotation around its axis, versus 24 hours for Earth.

The axis of Mars, like Earth's, is tilted in relation to the sun. This means that like Earth, the amount of sunlight falling on certain parts of the Red Planet can vary widely during the year, giving Mars seasons.

Mars' orbit: Quick facts

— Average distance from the sun: 141,633,260 miles (227,936,640 km). By comparison: 1.524 times that of Earth.

— Perihelion (closest solar approach): 128,400,000 miles (206,600,000 km). By comparison: 1.404 times that of Earth.

— Aphelion (farthest distance from the sun): 154,900,000 miles (249,200,000 km). By comparison: 1.638 times that of Earth.

However, the seasons that Mars experiences are more extreme than Earth's because the Red Planet's elliptical, oval-shaped orbit around the sun is more elongated than that of any of the other major planets. When Mars is closest to the sun, its southern hemisphere is tilted toward our star, giving the planet a short, warm summer, while the northern hemisphere experiences a short, cold winter. When Mars is farthest from the sun, the northern hemisphere is tilted toward the sun, giving it a long, mild summer, while the southern hemisphere experiences a long, cold winter.

The tilt of the Red Planet's axis swings wildly over time because it's not stabilized by a large moon. This situation has led to different climates on the Martian surface throughout its history. A 2017 study suggests that the changing tilt also influenced the release of methane into Mars' atmosphere, causing temporary warming periods that allowed water to flow.

Mars missions and research

Mars is one of the most explored bodies of our solar system. (Image credit: Future)

The first person to observe Mars with a telescope was Galileo Galilei, in 1610. In the century following, astronomers discovered the planet's polar ice caps. In the 19th and 20th centuries, some researchers — most famously, Percival Lowell — believed they saw a network of long, straight canals on Mars that hinted at a possible civilization. However, these sightings proved to be mistaken interpretations of geological features.

A number of Martian rocks have fallen to Earth over the eons, providing scientists a rare opportunity to study pieces of Mars without having to leave our planet. One of the most controversial finds was Allan Hills 84001 (ALH84001) — a Martian meteorite that, according to a 1996 study, likely contains tiny fossils and other evidence of Mars life. Other researchers cast doubt on this hypothesis, but the team behind the famous 1996 study have held firm to their interpretation, and the debate about ALH84001 continues today.

In 2018, a separate meteorite study found that organic molecules — the carbon-containing building blocks of life, although not necessarily evidence of life itself — could have formed on Mars through battery-like chemical reactions.

Robotic spacecraft began observing Mars in the 1960s, with the United States launching Mariner 4 in 1964 and Mariners 6 and 7 in 1969. Those early missions revealed Mars to be a barren world, without any signs of the life or civilizations people such as Lowell had imagined there. In 1971, Mariner 9 orbited Mars, mapping about 80% of the planet and discovering its volcanoes and big canyons.

The Soviet Union also launched numerous Red Planet spacecraft in the 1960s and early 1970s, but most of those missions failed. Mars 2 (1971) and Mars 3 (1971) operated successfully but were unable to map the surface due to dust storms. NASA's Viking 1 lander touched down on the surface of Mars in 1976, pulling off the first successful landing on the Red Planet. Its twin, Viking 2, landed six weeks later in a different Mars region.

The Viking landers took the first close-up pictures of the Martian surface but found no strong evidence for life. Again, however, there has been debate: Gil Levin, principal investigator of the Vikings' Labeled Release life-detection experiment, forever maintained that the landers spied evidence of microbial metabolism in the Martian dirt. (Levin died in July 2021, at the age of 97.)

The next two craft to successfully reach the Red Planet were Mars Pathfinder, a lander, and Mars Global Surveyor, an orbiter, both NASA craft that launched in 1996. A small robot onboard Pathfinder named Sojourner — the first wheeled rover ever to explore the surface of another planet — ventured over the planet's surface, analyzing rocks for 95 Earth days.

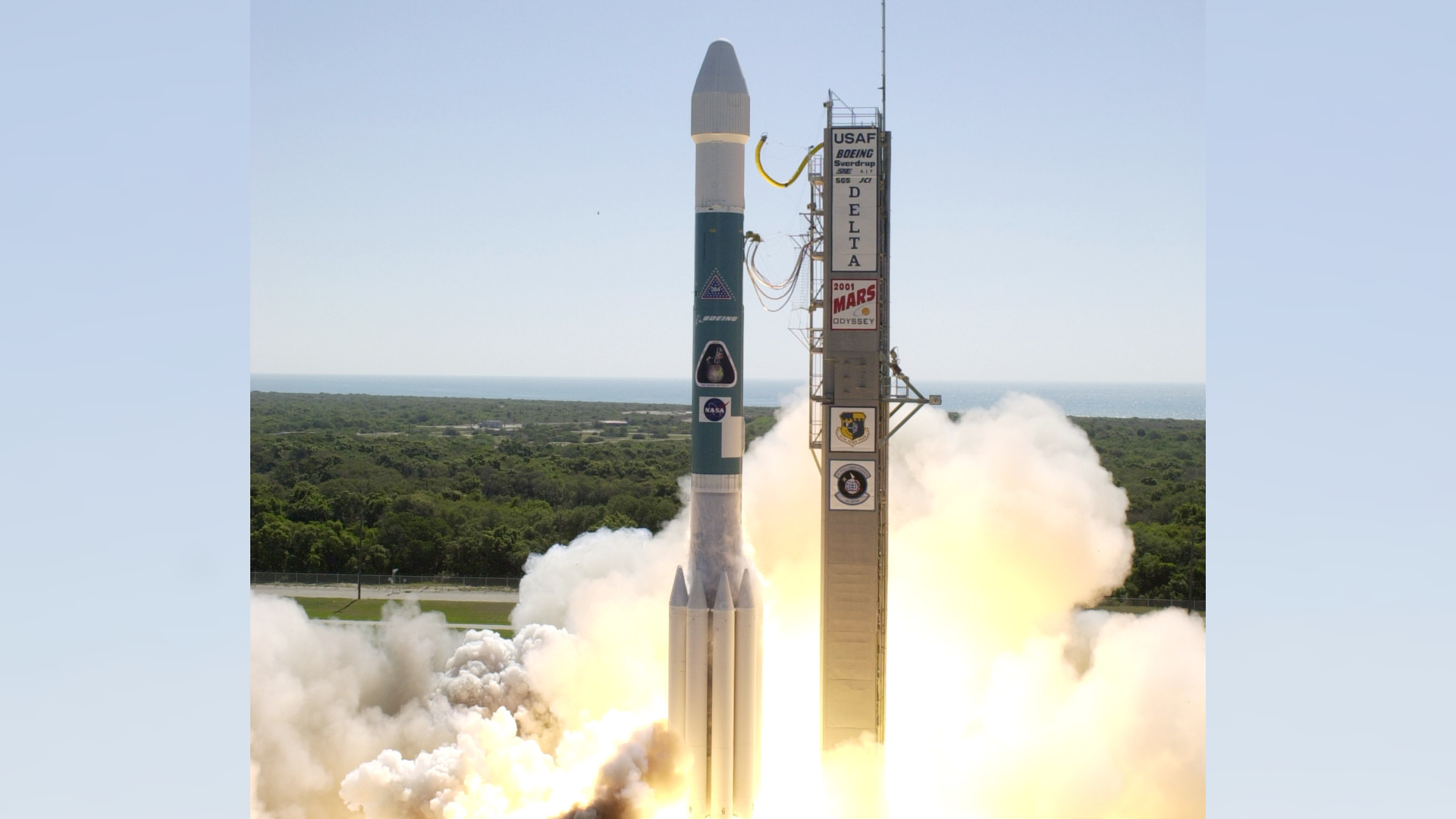

In 2001, NASA launched the Mars Odyssey orbiter, which discovered vast amounts of water ice beneath the Martian surface, mostly in the upper 3 feet (1 meter). It remains uncertain whether more water lies underneath, since the probe cannot see water any deeper.

The Mars Odyssey launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida on April 7, 2001. (Image credit: NASA)

In 2003, Mars passed closer to Earth than it had anytime in the past 60,000 years. That same year, NASA launched two golf-cart-sized rovers, nicknamed Spirit and Opportunity, which explored different regions of the Martian surface after touching down in January 2004. Both rovers found many signs that water once flowed on the planet's surface.

Spirit and Opportunity were originally tasked with three-month surface missions, but both kept roving for far longer than that. NASA didn't declare Spirit dead until 2011, and Opportunity was still going strong until that dust storm hit in mid-2018.

In 2008, NASA sent a lander called Phoenix to the far northern plains of Mars. The robot confirmed the presence of water ice in the near subsurface, among other finds.

In 2011, NASA's Mars Science Laboratory mission sent the Curiosity rover to investigate Mars' past potential to host life. Not. long after landing inside the Red Planet's Gale Crater in August 2012, the car-sized robot determined that the area hosted a long-lived, potentially habitable lake-and-stream system in the ancient past. Curiosity has also found complex organic molecules and documented seasonal fluctuations in methane concentrations in the atmosphere.

NASA has two other orbiters working around the planet — the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and MAVEN (Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution), which arrived at Mars in 2006 and 2014, respectively. The European Space Agency (ESA) also has two spacecraft orbiting the planet: Mars Express and the Trace Gas Orbiter.

In September 2014, India's Mars Orbiter Mission also reached the Red Planet, making it the fourth nation to successfully enter orbit around Mars.

In November 2018, NASA landed a stationary craft called Mars InSight on the surface. As noted above, InSight is investigating Mars' internal structure and composition, primarily by measuring and characterizing marsquakes.

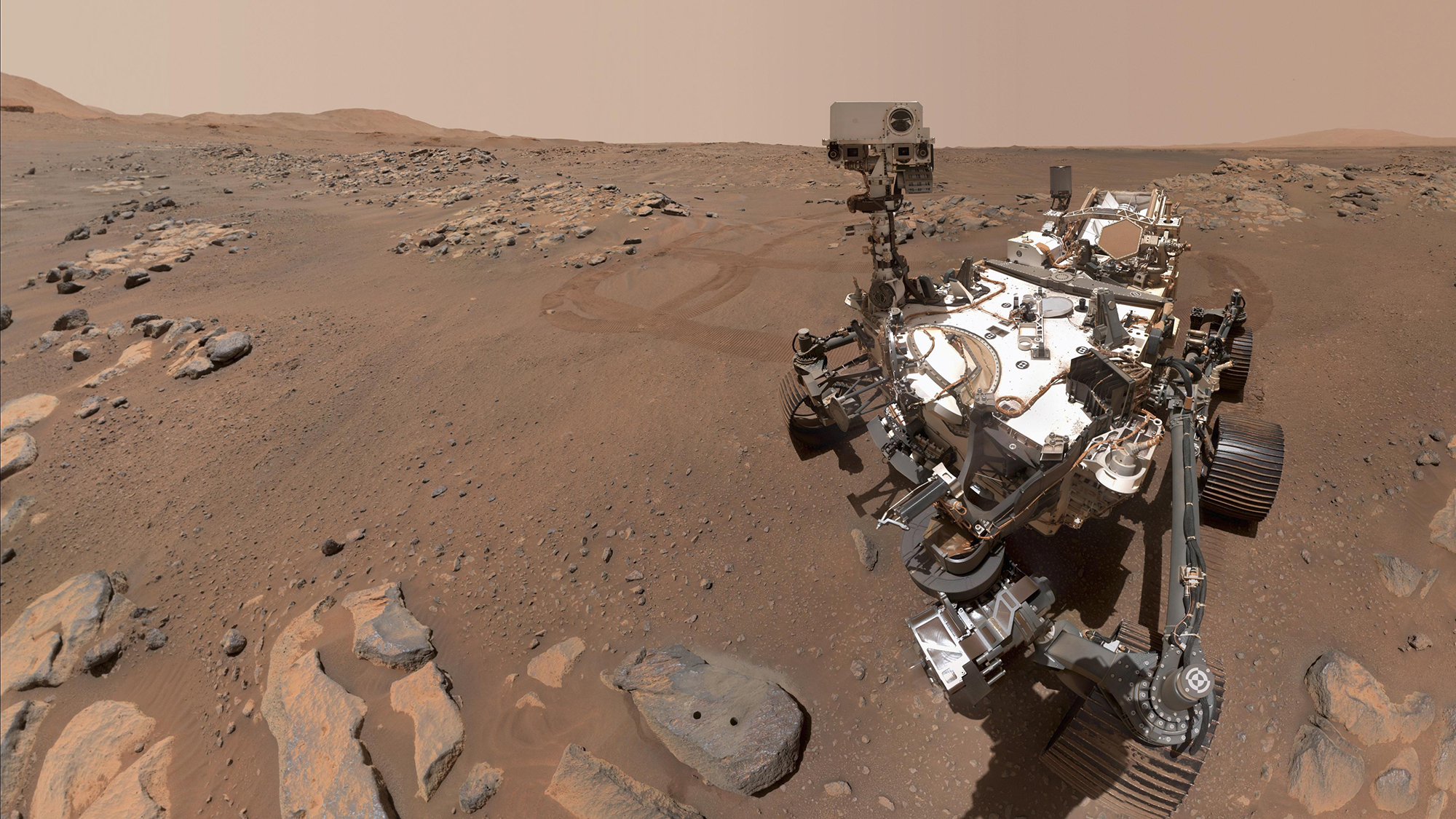

NASA's Perseverance Mars rover took this selfie over a rock nicknamed "Rochette," on Sept. 10, 2021. (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS)

NASA launched the life-hunting, sample-caching Perseverance rover in July 2020. Perseverance, which is about the same size as Curiosity, landed on the floor of Mars' Jezero Crater in February 2021 along with a tiny, technology-demonstrating helicopter known as Ingenuity.

As of September 2021, Ingenuity had made more than a dozen flights on Mars, showing that aerial exploration of the planet is feasible. Perseverance documented the 4-pound (1.8 kg) chopper's early flights, then began focusing in earnest on its own science mission. The big rover has already collected several samples, part of a big cache that will be brought back to Earth, perhaps as soon as 2031, by a joint NASA-ESA campaign.

July 2020 also saw the launch of the United Arab Emirates' first Mars mission, called Hope, and China's first fully homegrown Mars effort, Tianwen 1. The Hope orbiter arrived at Mars in February 2021 and is studying the planet's atmosphere, weather and climate.

Tianwen 1, which consists of an orbiter and a lander-rover duo, also reached Mars orbit in February 2021. The landed element touched down a few months later, in May. The Tianwen 1 rover, called Zhurong, soon rolled down the landing platform's ramp and began exploring the Martian surface.

ESA is also working on a Mars rover named Rosalind Franklin, previously known as the ExoMars rover. The rover is a multi-part European-led program to explore Mars, both on the surface and from above. The program has been delayed several times and is unlikely to launch before 2028.

Future human missions

Robots aren't the only ones getting a ticket to Mars. A workshop group of scientists from government agencies, academia and industry have determined that a NASA-led manned mission to Mars should be possible by the 2030s.

In late 2017, the administration of President Donald Trump directed NASA to send people back to the moon before going to Mars. NASA is working on this goal via a program called Artemis, which aims to establish a sustainable, long-term human presence on and around the moon by the late 2020s. The lessons and skills learned from this lunar effort will help pave the way for putting boots on Mars, NASA officials have said.

Robotic missions to the Red Planet have seen much success in the past few decades, but it remains a considerable challenge to get people to Mars. With current rocket technology, it would take at least six months for people to travel to Mars. Red Planet explorers would therefore be exposed for long stretches to deep-space radiation and to microgravity, which has devastating effects on the human body. Performing activities in the moderate gravity on Mars could prove extremely difficult after many months in microgravity. Research into the effects of microgravity continues on the International Space Station.

NASA isn't the only entity with crewed Mars aspirations. Other nations, including China and Russia, have also announced their goals for sending humans to the Red Planet.

And Elon Musk, the founder and CEO of SpaceX, has long stressed that he established the company back in 2002 primarily to help humanity settle the Red Planet. SpaceX is currently developing and testing a fully reusable deep-space transportation system called Starship, which Musk believes is the breakthrough needed to get people to Mars at long last.

Additional resources

Explore Mars in more detail with NASA's Mars Exploration Program. Read about Mars' climate in more detail with the National Weather Service. Send your name to Mars on NASA's next flight to the Red Planet.

Bibliography

NASA. Mars fact sheet. NASA. Retrieved July 11, 2022, from www.nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/marsfact.html

NASA. Mars. NASA. Retrieved July 11, 2022, from www.solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/mars/overview/

NASA. NASA Mars Exploration. NASA. Retrieved July 11, 2022, from https://mars.nasa.gov/

NASA. Send your name to Mars. NASA. Retrieved July 11, 2022, from www.mars.nasa.gov/participate/send-your-name/future

US Department of Commerce, N. O. A. A. The planet Mars. National Weather Service. Retrieved July 11, 2022, from www.weather.gov/fsd/mars

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us