Venus' atmosphere: Composition, clouds and weather (original) (raw)

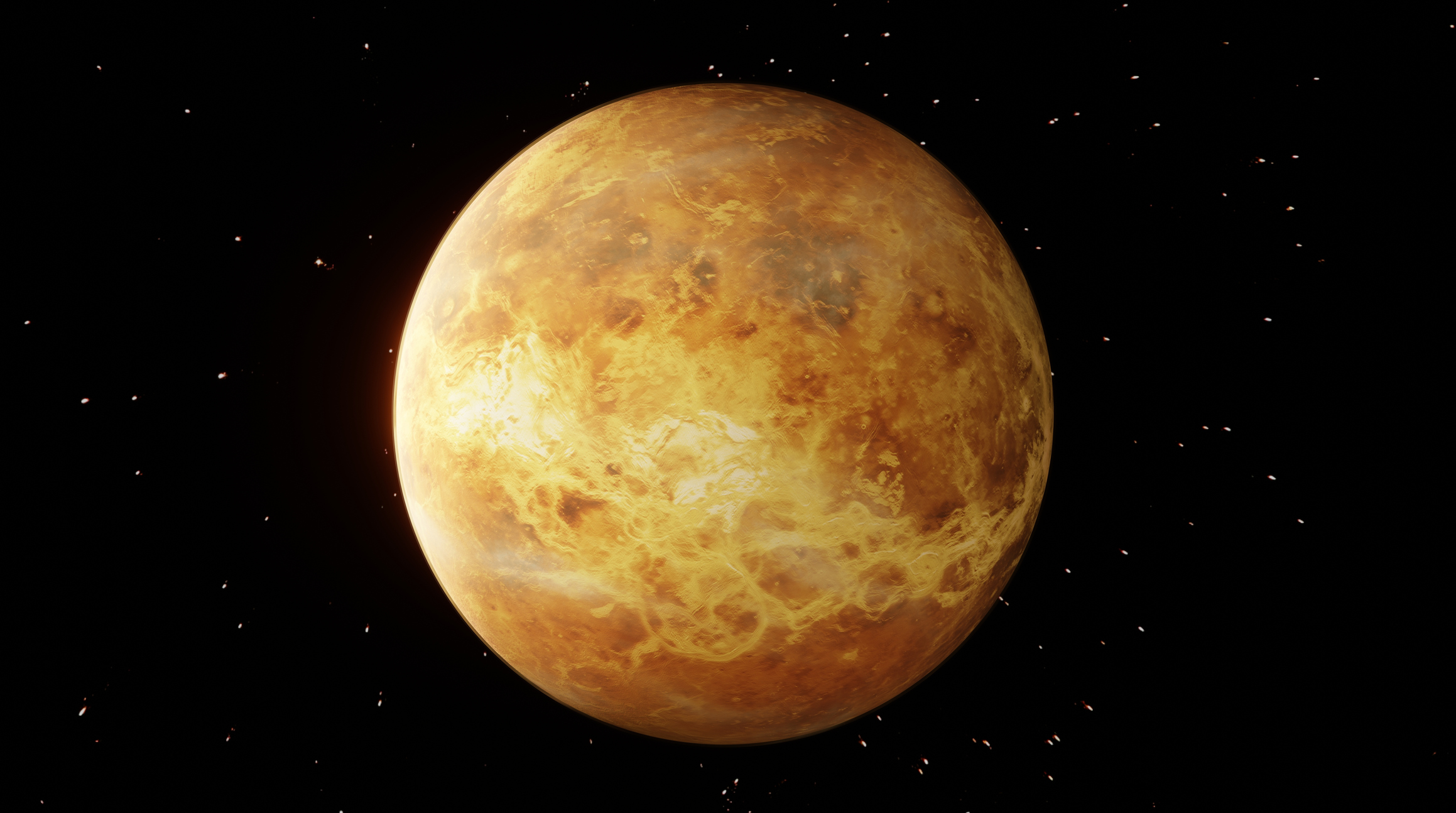

Venus' atmosphere has led to an extreme version of the same greenhouse effect causing climate change on Earth. (Image credit: ARTUR PLAWGO/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY/Getty Images)

Venus, the second planet from the sun, is blanketed by an extremely thick, dense atmosphere — the densest terrestrial atmosphere in the solar system, according to The Planetary Society.

Venus' atmosphere is made mostly of carbon dioxide, according to NASA. The planet is also shrouded in clouds of sulfuric acid. Because of its heat-trapping atmosphere, Venus has the hottest surface of any planet in the solar system.

Related: The 10 most Earth-like exoplanets

Venus is often called Earth's twin because of its similar size and composition. Although the conditions on Venus are far different from those on Earth, Venus' thick atmosphere has led to an extreme version of the same greenhouse effect that's causing climate change on Earth. Researchers think that early in its history, Venus had a thinner atmosphere and a more Earth-like environment.

There are small areas of Venus' atmosphere that have more moderate temperatures. In recent years, researchers detected signals that they said could be related to life. However, subsequent findings have called those results into question, and the topic is heavily debated.

Atmospheric composition

Venus' atmosphere is made up of 96% carbon dioxide, 3% nitrogen and 1% other gases. These other gases are mainly sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, water vapor, helium, argon and neon, according to NASA. Researchers have also found a small amount of oxygen in a thin layer of the planet's atmosphere, though it is atomic oxygen (O), not the molecular oxygen (O2) we breathe. In comparison, Earth's atmosphere is about 78% nitrogen, 21% oxygen and 1% other gases, including argon, carbon dioxide, neon and others.

Because carbon dioxide is very dense, Venus' atmosphere is about 93 times denser than Earth's, according to The Planetary Society. If you could stand on Venus' surface, it would be like having the weight of a small car on every square inch of your body, or like being 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) under the surface of the ocean on Earth without any protective gear — you would be crushed immediately.

Venus atmosphere FAQs

Can life exist in Venus' atmosphere?

Though no definitive signs of life have been detected in Venus' atmosphere, some researchers think it is possible for life to exist in the comparatively moderate climate and reduced atmospheric pressure of the planet's atmosphere. Though these conditions would still be harsher than most on our planet, some microorganisms on Earth, dubbed "extremophiles," live in similar conditions.

Did Venus have oxygen?

Though scientists have detected small amounts of atomic oxygen in Venus' atmosphere, there's no sign Venus has ever had notable molecular oxygen in its atmosphere. It's possible that Venus' evaporating oceans resulted in a lot of oxygen in the atmosphere, but it's unclear what might have happened to it. There's also no reason to suspect Venus had molecular oxygen in its atmosphere even if it once was similar to the early Earth, since the Earth's early atmosphere did not contain much oxygen until it started being produced by life.

Is Venus' atmosphere high pressure?

Yes, the atmospheric pressure on Venus is incredibly high, particularly at its surface. If you could stand on Venus, the pressure would be like having the weight of a small car on every square inch of your body or being about 0.6 miles under the ocean on Earth.

Clouds and atmospheric layers

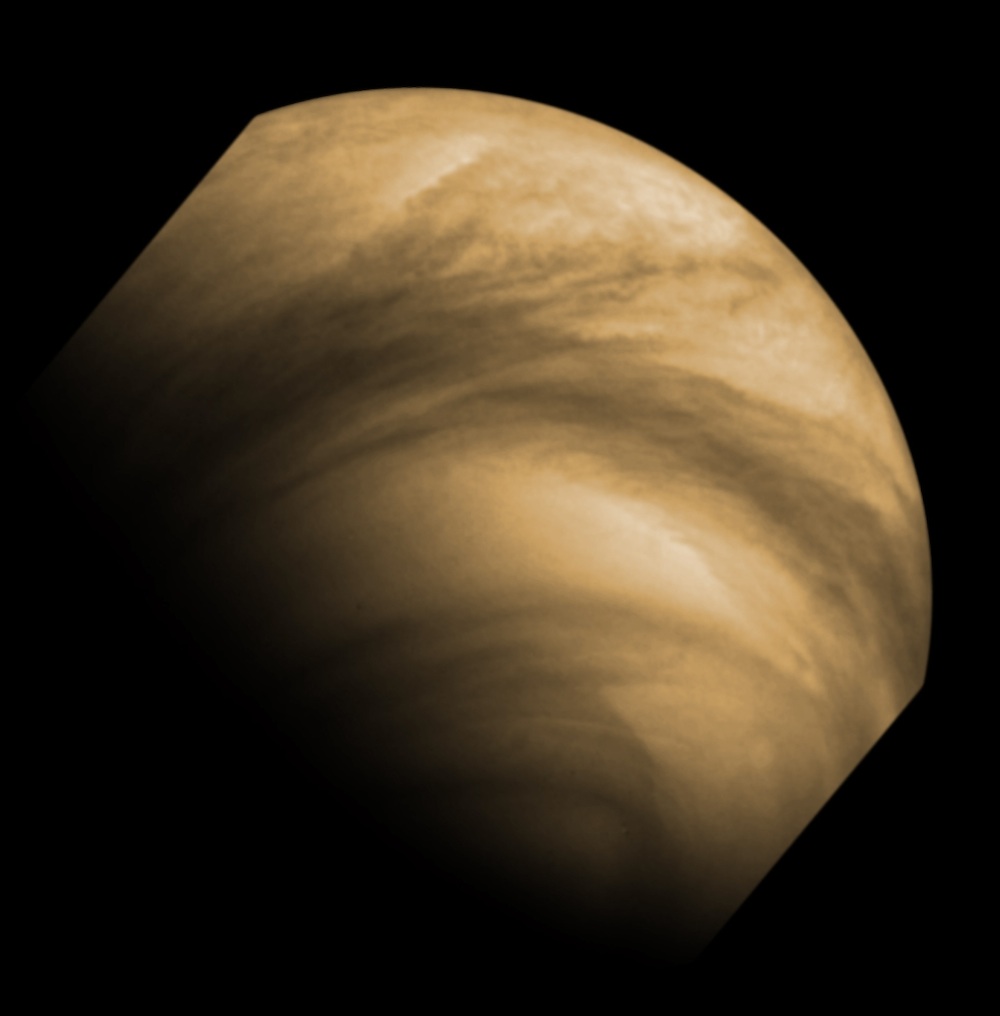

False-colour image of cloud features seen on Venus by the Venus Monitoring Camera (VMC) on Venus Express. (Image credit: ESA/MPS/DLR/IDA)

Venus' clouds encircle the entire planet and are made mostly of sulfuric acid, with small amounts of solid sulfur, nitrosylsulfuric acid and phosphoric acid, according to Britannica. They are extremely thick. The main portion extends from about 30 to 42 miles (48 to 68 km) above the planet's surface. Thinner hazes reach from about 20 to 56 miles (32 to 90 km) above the surface.

There are three main layers of Venus' atmosphere. The upper atmosphere has an extremely variable temperature and extends down to 60 miles (100 km) above the surface. Below that is the middle atmosphere, or stratosphere, then the lower atmosphere, or troposphere, extends from the surface to about 37 miles (60 km) above it and contains the cloud layers and the cloud-free area just above the surface. It gets rapidly hotter near the surface. Venus also has an ionosphere, or layer of charged particles, above its upper atmosphere.

Climate and weather

Apart from the sun, the surface of Venus is the hottest thing in the solar system. It's even hotter than the surface of Mercury, which is closer to the sun. This is due to Venus' thick, heat-trapping atmosphere and its runaway greenhouse effect. Venus' surface can reach 860 degrees Fahrenheit (460 degrees Celsius), which is hot enough to melt lead. There is not much difference between the temperature during the day and at night, according to the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). Venus has very little seasonal variation because its axis is barely tilted.

At its surface, Venus has light winds, but up in the middle cloud layer, they can blow at a ferocious 223 mph (360 km/h) according to JAXA.

These wind speeds slow down near the equator. Though Venus as a planet rotates only three times in two Earth years, its clouds circle the planet once every four days. Sulfuric acid also rains down on Venus, but the extreme surface heat causes the rain to evaporate before it reaches the surface.

Was Venus always this hellish?

Researchers think Venus used to be an Earth-like planet covered with oceans. The sun was cooler and dimmer billions of years ago, but as it became brighter and hotter, Venus' ocean started to evaporate. This evaporation is thought to have kicked off Venus' runaway greenhouse effect. Large amounts of water vapor, which is a greenhouse gas, evaporated from the oceans and wound up in the atmosphere, warming the planet and causing even more evaporation of the oceans.

Researchers think the evaporation of Venus' oceans triggered the halting of the planet's plate tectonics, the geologic system on Earth that causes the movement of pieces of a planet's crust. Plate tectonics also causes carbon in rock to be periodically pushed deep underground. Researchers think that without plate tectonics, Venus' carbon ended up in the planet's atmosphere, exacerbating the greenhouse effect and turning it into the extreme environment we know today.

Potential for life

Artist's impression of a volcano erupting on Venus. (Image credit: ESA/AOES)

Despite Venus' hellish conditions, there has been speculation that its atmosphere could harbor life, but this is hotly debated. Portions of Venus' atmosphere are cooler and have less-harsh conditions than its surface. Because life could have evolved in the planet's early, Earth-like history, some researchers think life might have adapted to Venus' changing surface, moving to its atmosphere.

In 2020, scientists reported that they'd detected a gas called phosphine in Venus' atmosphere, which on Earth is produced by life. However, a less harsh reanalysis of the data revealed possible errors, and the authors revised the estimate of phosphine in the atmosphere to be much lower. Since then, other missions have found that there is likely very little or no phosphine in Venus' atmosphere.

Venus atmosphere expert Q&A

James Lyons is a planetary scientist who studies the chemistry of planetary atmospheres. He has researched the atmospheres of Mars, Venus, and the early Earth, as well as the chemical process that formed our solar system.

How have researchers thought sulfur clouds formed in Venus' atmosphere?

It has long been known (late 1960s) that the clouds on Venus consist largely of sulfuric acid droplets. It has long been suspected that polysulfur is also involved in cloud particle and haze formation in the Venusian atmosphere. Polysulfur is a form of pure sulfur consisting of different numbers of sulfur atoms. The most common examples are S2, S4 and S8, with the numbers indicating the number of S atoms in the polysulfur molecule. The normal yellow form of sulfur powder is made up of S8 molecules. The clouds on Venus appear to be made of sulfuric acid droplets that condense onto smaller particles made of polysulfur molecules. The polysulfur molecules are produced by photochemical (ultraviolet light) destruction of SO2 (sulfur dioxide) in the atmosphere.

How does your research revise this understanding?

In our 2022 Nature Communications paper, we identified a new photochemical pathway for S2 production. This is important because the formation of S2 was the slowest step in producing polysulfur particles. We showed that it forms rapidly as a result of a sequence of reactions involving dimers of SO — that is, two SO (sulfur monoxide) molecules combined to make an OSSO molecule. Photolysis of OSSO produces S2O, which then reacts with SO to produce S2. It's a complicated set of reactions, as is often the case with sulfur photochemistry. Another important aspect of our work was the use of computational chemistry techniques to determine the rates of reactions. This allowed us to accurately simulate reactions that have never been studied in the laboratory.

Why might it be important to understand the chemistry of how sulfur clouds form in Venus' atmosphere?

Understanding sulfur cloud chemistry is important for two reasons. First, NASA will be sending the DAVINCI spacecraft to Venus around 2030. Analysis of cloud chemistry will be a significant part of that mission. Second, the work that we do to understand sulfur chemistry in the Venus atmosphere will help us to better understand the atmosphere of the ancient Earth before our atmosphere was oxygenated. The rise of oxygen about 2.4 billion years ago was a major event in Earth history that we still do not entirely understand.

Additional Resources

Ever wondered what it's like to stand on the surface of Venus, this Planetary Society article explores what it would feel like. Learn more about past, current and future missions to Venus on NASA's website and these resources from the Planetary Society

Bibliography

NASA, "Venus: Facts." https://science.nasa.gov/venus/facts/

The Planetary Society, "Venus, Earth's twin sister." https://www.planetary.org/worlds/venus

The Planetary Society, "What would it be like to stand on the surface of Venus?" https://www.planetary.org/articles/what-would-it-be-like-to-stand-on-the-surface-of-venus

Cabbage, Michael and Leslie MacCarthy, "NASA climate modeling suggests Venus may have been habitable," NASA. https://climate.nasa.gov/news/2475/nasa-climate-modeling-suggests-venus-may-have-been-habitable/

Dunham, Will, "Scientists detect oxygen in noxious atmosphere of Venus," Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/science/scientists-detect-oxygen-noxious-atmosphere-venus-2023-11-08/

Williams, Dave. "Venus Fact Sheet," NASA. https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/venusfact.html

Squyres, Steven W., "Venus," Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Venus-planet/The-atmosphere

Fraknoi, Andrews, David Morrison, and Sidney C. Wolff. "10.3 The Massive Atmosphere of Venus," Astronomy. https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/astronomybc/chapter/10-3-the-massive-atmosphere-of-venus/

Howells, Kate, "Life on Venus: Your Questions Answered." The Planetary Society. https://www.planetary.org/articles/life-on-venus-your-questions-answered

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Rebecca Sohn is a freelance science writer. She writes about a variety of science, health and environmental topics, and is particularly interested in how science impacts people's lives. She has been an intern at CalMatters and STAT, as well as a science fellow at Mashable. Rebecca, a native of the Boston area, studied English literature and minored in music at Skidmore College in Upstate New York and later studied science journalism at New York University.