Suffolk Churches (original) (raw)

Listen: come with me. We’ll set off from the Queen’s Head at Blyford, a fine and welcoming pub across the road from that village’s little church. Perhaps we’ll have just had lunch, and we’ll be sitting outside with a couple of pints of Adnams. You’d like to stay there in the sunshine for the rest of the afternoon, but I’m going to take you somewhere special, so stir yourself. You are probably thinking it is Blythburgh, Suffolk’s finest church a couple of miles away on the main A12. But it isn’t. Nor is it the church at Wenhaston, a mile away across the bridge, and home of the Wenhaston Doom, one of Suffolk’s greatest medieval art treasures. But no, you’ve already seen that.

I'm going to take you somewhere of which you may not even have heard. Within a few miles of the pub sign (notice that it features St Etheldreda, whose father King Anna was killed in battle on the Blyth marshes) there is a third of Suffolk’s finest churches. It is the least known of the three, partly because it is so carefully hidden, so secreted away, and partly because Simon Jenkins missed it out of his book England’s Thousand Best Churches, and like many people you take too much notice of it.

Blyford is on the main road between Halesworth and Dunwich, but we are going to take a narrow lane that you might almost miss if you weren’t with me. It leads northwards, and is quickly enveloped by oak-buttressed hedgerows, beyond which thin fields spread. Pheasants scuttle across the road in front of us. A hare watches warily for a moment before kicking sulkily back into the ditch (we are on foot perhaps, or bicycle). Occasional lanes thread off into the woods and towards the sea.

After a couple of miles, we reach the obscenity of a main road, and cross it quickly, leaving it behind us. Now, the lane narrows severely, the banks steepening, trees arching above us. They guard the silence, until our tunnel doglegs suddenly, and an obscure stream appears beyond the hedgerow. Once, on a late winter afternoon, my dream was disturbed here by a startled heron rising up, its bony legs clacking dryly as it took flight over my head. I felt the rush of its wings.

This road was not designed for cars. Instead, it traces the ancient field pattern, cutting across the ends of strips and then along the sides, connecting long-vanished settlements. The lane splits (we take the right fork) and splits again (the left) and suddenly we are descending steeply into a secret glade shrouded in ancient tree canopies. The lane curves, narrows and opens – and here we are. Still, you might not notice it, because the church is still camouflaged by the trees, and the absurdity of the neighbouring bungalow with its kitschy garden may distract you. But to your right, in a silent velvet graveyard sits St Andrew, Westhall. It has been described as Suffolk’s best kept secret.

I hope that I can convey to you something of why this place is so special. Firstly, notice the unusual layout of the building as you walk around it. That fine late 13th century tower, not too high despite its post-Reformation bell-stage, organic and at one with the trees, a small Norman church spreading to the east of it. And then, to the north, a large 13th century nave, thatched and rustic. It was designed for this graveyard, for this glade. Neither has changed much. Beyond it, the grand 14th century chancel, rudely filling almost the entire east end of the graveyard. Perhaps as we step around to the north side the same thing will happen as happened to me one muggy Saturday afternoon in July 2003, when I surprised a tawny owl daydreaming on a headstone. he took one look at me and then threw himself furiously into the air and away.

Your first thought may be that here we have two churches joined together – and this is almost exactly right. Here at Westhall, there was a Norman church, an early one. Several hundred years later a tower was built to the west of it, and then the vast new nave to the north. A hundred years later came the chancel. Perhaps the east end of the Norman church was rebuilt at this time. Mortlock thinks that there was once a Norman chancel, and this may be so. The old church became a south aisle, the particular preserve perhaps of the locally important Bohun family. They married into the famous Coke family, who we have already met at nearby Bramfield.

And so, we step inside. We may do so through the fine north porch. It is a wide, open one, clearly intended for the carrying out of parish business. It was probably the last substantial part of the church to be built, on the eve of the Reformation. The door appears contemporary. Or, I might send you round to step in through the Norman doorway on the south side, into the body of the original church. Both entrances are usually open.

You expect dust and decay perhaps, in such a remote spot. But this is a well-kept church, lovingly maintained and well-used. Although there are a couple of old benches scattered about, most of the seating is early 19th century, with that delightful cinema curve to the western row which was fashionable immediately before the Oxford Movement and the Camden Society sent out their great re-sacramentalising waves, and English churches would never be the same again.

If you step in from the north, you are immediately confronted with something so wonderful that we are going to pretend you cannot believe your eyes, and you pass it by. Instead, walk into the Norman south side and draw back the curtain beneath the tower. Walk to the western wall, and turn back. You are confronted with the main entrance of a grand post-conquest church, probably about 1100. Before the tower was built you would have been standing outside of the main entrance. Surviving faces in the unfinished ranges of the arch look like something out of Nick Park's Wallace and Grommit. Above the arch is an arcade of windows, the central one open. Almost a thousand years ago, it would have thrown summer evening light on the altar.

As you step back into the aisle, it is now easy to see it as the nave it once was. The northern wall has now gone, replaced by a low arcade, and you step northwards through it into the wideness of the modern (it is only 600 years old!) nave. Here, then, let us at last allow ourselves an exploration of Suffolk’s other great medieval art survival. This is Westhall’s famous font, one of the seven sacrament series, but more haunting than all the others because it still retains almost all its original colour. The other feature of the font that is quite extraordinary is the application of gessowork for the tabernacled figures between the faces. This is plaster, moulded on and allowed to dry – it can then be carved. It is sometimes used on wood to achieve fine details, but rarely on stone. Was it once found widely elsewhere? How has it survived here? The font asks more questions than it answers.

How did it survive? Suffolk has 13 Seven Sacrament fonts in various states of repair. Those nearby at Blythburgh, Wenhaston and Southwold are clearly from the same group as this one, but have been completely effaced. Other good ones survive nearby at Weston and Great Glemham, at Monk Soham, at neighbours Woodbridge and Melton, neighbours Cratfield and Laxfield, at Denston in the south west and at Badingham. We don’t know how many others there might have been. Probably not many, for most East Anglian churches have a surviving medieval font of another design. The surviving panels were probably plastered over during the long Reformation night (the damage to the figures may be a result of the reformers making the faces flush rather than any attempt at iconoclasm) and they were also all probably once coloured, and paint survives in small amounts on some of the others in the series. So why has only this one survived with so much colour intact?

The Mass panel is perhaps the most familiar, because a photograph of it was used as the cover of the original edition of Eamonn Duffy’s majestic The Stripping of the Altars. A priest faces away from us towards the altar, and raises the host. He has had his head removed by a reforming blow. On many Seven Sacrament fonts he is shown flanked by two acolytes, but here the two figures are dressed in fine clothes and appear to be a man and a woman, so I think they must be the donors of the font. Several other Seven Sacrament fonts have the donors kneeling in one of the panels. The next panel, anti-clockwise from the Mass panel, depicts the sacrament of Last Rites. The dying man lies in the bed. The priest, in the foreground, bends to anoint his chest with holy oil. The man's wife stands at the foot of the bed, and behind are two acolytes, one holding what is either a book or a chrismatory.

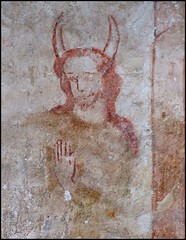

Continuing anti-clockwise, next comes Confession. The priest sits in a chair, the parishioner making his confession kneeling before him, guarded by an angel. On the right, the devil sneaks out, his tail between his legs. Matrimony is next. The priest, wearing crossed bands, joins the hands of the happy couple. Two witnesses look on, one apparently carrying a bag. Next is Confirmation, which the priest is administering to two infants held in their parents arms. An acolyte stands behind, holding a chrismatory with the holy oils. After that is Baptism, with a font not unlike the Westhall font! The priest totally immerses the child in the medieval manner. An acolyte stands beside him with the holy oils while two godparents look on. The penultimate panel is Ordination, the ordinand kneeling before a bishop. Two acolytes behind hold a book and a chrismatory. Finally, the odd panel out depicts the Baptism of Christ. Christ stands centrally, John the Baptist stands on the right pouring water from a ewer over him, and what is probably a Bishop stands on the right.

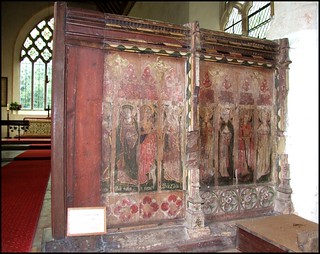

Turning east, we come to Westhall's famous screen. It's a bit of a curiosity. Firstly, the two painted ranges are clearly from different times and the work of different artists. On the 15th Century south side are female Saints, very similar in style to those on the screen at Ufford. The artists helpfully labelled them, and they are St Etheldreda (the panel bearing her left half has been lost) St Sitha, St Agnes, St Bridget, St Catherine, St Dorothy, St Margaret of Aleppo and finally one of the most essential Saints in the medieval economy of grace, St Apollonia - she it was who could be asked to intercede against toothache.

The depictions on the early 16th Century northern part of the screen are much simpler (Pevsner thought them crude) and were probably painted by a local artist. A dedicatory inscription runs along the top on this side. It is barely legible now, but the names Margarete and Tome Felton and Richard Lore and Margaret Alen are still discernible. The figures on this side of the screen are fascinating. They are all easily recognisable, and are fondly rendered. With one remarkable exception, they are familiar to us from many popular images.

The first is Saint James in his pilgrim's garb, as if about to set out for Santiago de Compostella. The power of such an image to medieval people in a backwater like north-east Suffolk should not be underestimated. Next comes St Leonard, associated with the Christian duty of visiting prisoners - perhaps this had a local resonance. Thirdly, there is a triumphant St Michael, one of the major Saints of the late medieval panoply, and then St Clement, the patron Saint of seafarers. This is interesting, because although Westhall is a good six miles from the sea, it is much closer to the Blyth river, which was probably much wider in medieval times. It seems strange to think of Westhall as having a relationship with the sea, but it probably did.

Now comes the remarkable exception. The next three panels represent between them the Transfiguration, with Christ on a mountain top in the middle between the two figures of Moses and Elijah. This is the only surviving medieval screen representation of the Transfiguration in England. Eamonn Duffy, in The Stripping of the Altars, argues that here at Westhall is priceless evidence of the emergence of a new cult on the eve of the Reformation, which would snuff it out. Another representation survived in a wall painting at Hawkedon, but has faded away during the last half century. The last panel is St Anthony of Egypt, recognisable from the dear little pig at his feet. I wonder if it was painted from the life.

When we can at last tear ourselves away from the screen, there is much else to explore. The wall painting on the north wall shows St Christopher, as you might expect. St Christopher had a special place in the hearts of medieval churchgoers, and he usually stands opposite the main south entrance so that the faithful could look in at the start of the day and receive his blessing. As a surviving inscription at Creeting St Peter reminds us, anyone who looks on the image in the morning would be spared a sudden death that day. This was important in an age when to die unconfessed was to risk purgatory, or even hell. But it is the two other figures in the illustration that are remarkable, though, for one of them is Moses, wearing his ‘horns of light’ (an early medieval mistranslation of ‘halo’). He receives the commandments from God the Father, who stands beside him.

There are a couple of other wall-paintings, including a beautiful flower-surrounded consecration cross beside the south door, and a painted image niche alcove in the eastern splay of a window in the south wall. This is odd, for it should have a figure in it, but none appears to have ever been painted there. Perhaps it was intended to have a statue placed in front of it, but the window sill is very steep, and it is hard to see how a statue could have been positioned there. Cameron Newham surmised that there had once been a stand below it, the base of which was canted in some manner, and that the sill had once been less steep (the base of the painting seems to suggest this).

Between the painted niche and consecration cross there are surviving traces of a large painting. It seems to consist of the leafy surrounds of seven large roundels. Mortlock wondered if it might have been a sequence of the Seven Works of Mercy as at Trotton in Sussex, but there is insufficient remaining to tell. Nicholas Bohun's tomb, in very poor repair, sits in the south-east corner. An associated brass gives you rather more information than you my might think you need. A George III royal arms hangs above. Stepping back into the south side, the angels that hold up the roof have lost their heads and wings, but are still beautiful. Several hold crowns, one holds a portative organ, another a shield with the lilies of the Annunciation.

If you haven't lost your appetite for the extraordinary, come back up into the apparently completely Victorianised chancel. Chalice brasses are incredibly rare, because of their Catholic imagery. Westhall had two of them, although unfortunately only the matrices survive. Then, look up. On one of the roof beams is an image of the Holy Trinity, with God the Father holding the Crucified Christ between his knees. There is probably a dove as well, although that is not visible from the ground. Indeed, the whole thing is too small, as if the artist hadn't really thought about the scale needed for it to be seen from the chancel floor. In the chancel windows, fragments of 14th and 15th Century glass remain.

At any time in any season this is a special place. I find it hard to resist a visit when ever I am cycling in these lanes to the south of Halesworth. It is always an extraordinary place to step into. Simon Jenkins described the parish churches of England as the greatest folk museum in the world, and that is exactly right, for of all Suffolk's churches this feels more than most to be a touchstone down the long generations to the people who built it and the people who worshipped in it. As you wander about wondering you may just catch out of the corner of your eye the movement of a 12th Century priest genuflecting at the south altar, a 15th Century peasant lighting a candle and telling her beads, the 18th Century blacksmith and ploughboy shuffling awkwardly on their bottoms during the long Sunday afternoon sermon. They were real people, who knew this place as their own. This is how we came to be.

Simon Knott, April 2020

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England Twitter.

| | The Churches of East Anglia websites are non-profit-making, in fact they are run at a loss. But if you enjoy using them and find them useful, a small contribution towards the costs of web space, train fares and the like would be most gratefully received. You can donate via Paypal. | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |