The Now of Glyn: An Interview with Glyn Dillon - The Comics Journal (original) (raw)

More than a decade ago, Glyn Dillon bid farewell to the comics industry, giving up a burgeoning career working on Vertigo titles like Egypt and Sandman for the chance to make films. Or at least storyboard them.

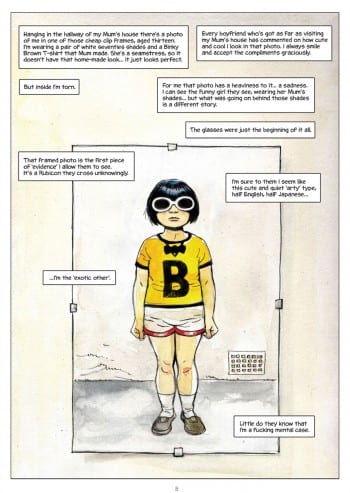

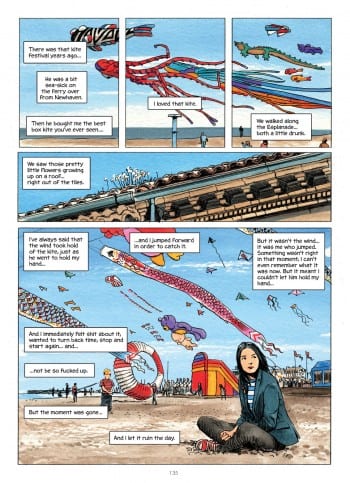

Now Dillon – the younger brother of Preacher artist Steve Dillon – is back, this time with his first full-length graphic novel, The Nao of Brown_. Published by SelfMade Hero, the book is centers on Nao Brown, a half-Japanese, half-British young artist living in London and suffering from a rather severe case of OCD, which manifests itself through a series of increasingly violent, homicidal thoughts. When not desperately trying to suppress these ugly ruminations (and keep anyone else from suspecting that there might be something “wrong” with her) she pursues a tentative romance with a burly washing machine repairman given to poetry._

I caught up with Dillon at the Small Press Expo in Bethesda, Maryland, last month. The book seemed to be garnering quite a bit of attention from visitors – SelfMadeHero sold out of copies on Sunday. While snacking on a sushi sampler platter in the downstairs area during a short signing break, Dillon graciously took the time to answer my questions.

CHRIS MAUTNER: How did you get started in comics?

CHRIS MAUTNER: How did you get started in comics?

GLYN DILLON: My brother is Steve Dillon of Preacher fame. He’s nine years my senior. When I was about six, he started drawing comics when he was about 16 for The Incredible Hulk weekly, a U.K. kind of thing. I think it’s normal to look up to your brother anyway, but when he’s drawing the Incredible Hulk … he’s a bit of a godhead figure for me. I always wanted to draw comics or get into the film industry from about the age of five or six.

I got my first professional job when I was about 17, drawing comics. I wasn’t as good as him. I drew comics for seven years. That led to some stuff for Vertigo and DC.

MAUTNER: Which titles?

DILLON: Shade the Changing Man with Pete Milligan. And I started doing a little miniseries with him called Egypt. The first [issue] I drew and inked myself, the second I just penciled and someone else inked. I did all the covers and somebody else took care of the art because I wanted to get out of comics at that stage and wanted to get into films. I wanted to do storyboarding. I’ve been storyboarding for about 17 years now. In that time I wanted to direct and I managed to do a little bit here and there. But getting stuff made in the film and TV world is really difficult. You need more than a good idea; you need a lot of luck and some strong wind behind you. I was doing stuff with Jamie Hewlett, who had all that success with Gorillaz, and you still can’t get stuff made. It’s difficult.

So I fell in love with the idea of doing comics again. It’s so nice that if I sit and plow away, I can have something to show at the end. I can get something done without endless meetings and all that kind of stuff.

MAUTNER: What was your impression initially working for DC? You said you left because you wanted to do other things. Were you disillusioned with the comics industry?

MAUTNER: What was your impression initially working for DC? You said you left because you wanted to do other things. Were you disillusioned with the comics industry?

DILLON: Before I was working for DC I was working for Deadline magazine. That was good because you could do what you wanted. You could have a silly idea in a pub with your friends and then two weeks later it was in W.H. Smith’s. Of course, I was too young to really appreciate that; I was in my late teens, early twenties. I didn’t realize how cool that was. And we weren’t getting a great page rate at all, a flat 50 quid a page maybe. Vertigo was just starting and there was a bit of a boom in America at the time. So they came in and were offering artists very healthy page rates. Being that age I was like “Yeah, I’ll do that.” And working with Pete Milligan as well, he was a bit of a hero.

When I wanted to leave, it wasn’t so much that I didn’t like comics. It was more that I wanted to get into films. I didn’t want to sit on my own as well. I was at the age where I wanted to go out and meet people and have some adventures. Whereas now I’m married and have two kids, so sitting at home is nice, it’s a bonus. You get to see the kids more often.

When I wanted to leave, it wasn’t so much that I didn’t like comics. It was more that I wanted to get into films. I didn’t want to sit on my own as well. I was at the age where I wanted to go out and meet people and have some adventures. Whereas now I’m married and have two kids, so sitting at home is nice, it’s a bonus. You get to see the kids more often.

MAUTNER: How did the idea for Brown come about?

DILLON: Initially it was going to be about Gregory, the male character. My little boy, before he was two, used to be scared of our washing machine. Not when it was on and making noise, but the round empty hole. He couldn’t walk past it, he was afraid of it. I thought, “Maybe he knows something we don’t.” So I wanted to do something about this washing machine repairman and have him linked up with another world or something. And Nao was going to be his love interest. Once I decided she was going to have OCD, she became a more interesting character and it started to feel like it was more her story than his so I flopped to her.

MAUTNER: Did you have to do any research into OCD? Do you have personal experience with the disease?

DILLON: My wife suffered with it as a child into her late teens. All around the time of coming up with the story I was discovering that because it wasn’t something she had [talked about] before. There seemed to be a strange week or two where there was some program about it on the TV, I was finding out about it from my wife and things kind of slotted into place. I found it fascinating.

DILLON: My wife suffered with it as a child into her late teens. All around the time of coming up with the story I was discovering that because it wasn’t something she had [talked about] before. There seemed to be a strange week or two where there was some program about it on the TV, I was finding out about it from my wife and things kind of slotted into place. I found it fascinating.

I was learning to meditate as well. In this meditation group there were other students saying how they couldn’t stop their minds from racing when they were trying to meditate, and there seemed to be parallels between that and OCD that all interested me at the time. All these things fed into it. Then I started to read books on it and I went to support groups and online forums. The OCD [Nao] has is not the same as my wife’s. It’s not my wife’s story but that kind of kickstarted my interest in the condition.

MAUTNER: It’s a different form of OCD; she’s not checking doorknobs.

DILLON: It’s called purely obsessional compulsive disorder. The compulsions which would be washing your hands, the obsession is the thought, those germs affect me and it will be terrible, so the compulsion is to wash your hands. You get caught in a loop. Her obsession is the horrible thought and then the compulsion is trying to counterbalance that with nice thoughts. They’re unseen compulsions in that particular kind of OCD. It’s easy to hide from other people so they’re less likely to know you’ve got it.

MAUTNER: How long did it take you to produce Brown and can you give me a breakdown of your working process?

DILLON: I wrote a one-page treatment and then an 11-page treatment to really show that I knew everything that was going to happen. And that’s when SelfMadeHero signed a deal. Then I had three months to write the script. It took about six drafts to do it. I spent two years to draw and paint it. I liked doing it that way. I had never written anything before. I had written for films before but only a first draft. So I’d never really finished anything of this length and magnitude. Having worked on films and TV, I was used to getting a script and then interpreting that. I thought, “That’s the way I’d like to do it.” It seems such a big, unwieldy thing; the thought of trying to lay it out visually as I went along seemed too daunting a process. I got the writing process out of the way and then got on with the thumbnailing and then got on with drawing. It seemed logical to me. But I still changed [the story] by the time I got to lettering at the end. That was the very last edit. It was nice because I wasn’t so precious about it anymore and I could lose whole word balloons and shift balloons around the page and really change things. It was much more pleasurable way to edit.

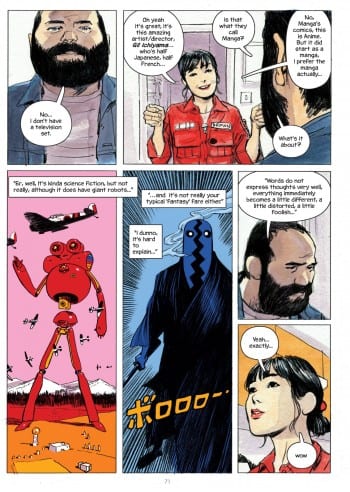

MAUTNER: I was interested in the fairy-tale Moebius sequences you have interspersed in the story. How did those come about?

MAUTNER: I was interested in the fairy-tale Moebius sequences you have interspersed in the story. How did those come about?

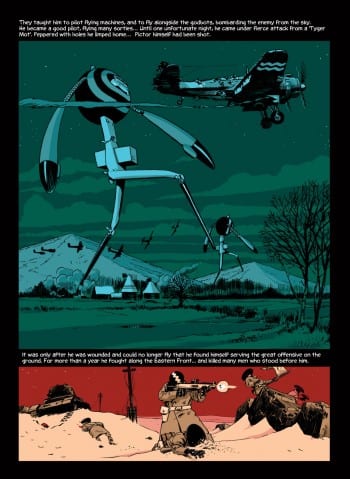

DILLON: I just wanted to have that story within a story and for her to have that interest for it to mirror or echo what’s going on in her life. The artist she’s into is based on Moebius and Miyazaki, so there’s half French and half Japanese [again]. Just echoing that thing. I liked the idea of doing two different styles in a book, the challenge of trying to make it work. Those pages took a lot longer to draw but they didn’t take as long to color.

MAUTNER: What did you use to color it?

DILLON: The majority of the book was done in watercolor. The Ichi pages are digital, Photoshop. I did use Photoshop to help with the watercolor. I would print out [pages] in the way they used to where they’d print out your black line and your blue line and a colorist might paint that and they’d have an acetate sheet over the top. You can do that at home now. I’d print out the black line at a lower capacity onto watercolor paper, paint that and then scan that back in and put it together with the black line again. So if I fucked up I could just print out a new page.

MAUTNER: It seems like you have a nice ear for conversations, especially the back and forth between friends. Is that based on your own experiences?

MAUTNER: It seems like you have a nice ear for conversations, especially the back and forth between friends. Is that based on your own experiences?

DILLON: Some of them are. One of Steve’s embarrassing moments is one of my embarrassing moments. I’ll say no more.

MAUTNER: Was that important to you, to get that sense of everyday reality?

DILLON: Yeah, definitely. Especially when you jump into these morbid fantasies. Someone who read it over the weekend said to me that at the beginning, because you often see violent things happen in comics, you weren’t sure whether these things were really happening or not.

MAUTNER: You don’t couch it either. Not initially at least.

DILLON: Yeah. What I really didn’t want to do was a book that explained OCD to people that didn’t know anything about it. I wanted to do a book where if you had OCD, you’d recognize it and understand it. One of the films I got to watch as reference it’s a good film called Dirty Filthy Love. It’s got Michael Sheen in it. It’s really good and it did a good job of explaining what OCD was. When I watched it I realized that’s not what I wanted to do. I wanted to make it almost incidental, not trying to explain it to someone. It’s not even mentioned in the book except on the dust jacket.

MAUTNER: That being the case, what’s the initial response been like? Have you heard from people that have OCD?

DILLON: No. The people who have read it have been very nice, but hopefully someone will read it and it will connect with them. That was the whole point of doing it.

DILLON: No. The people who have read it have been very nice, but hopefully someone will read it and it will connect with them. That was the whole point of doing it.

MAUTNER: Without spoiling anything I wanted to ask you about the ending, where she goes through a trauma that forces her to reassess things. What were your thoughts as far as that goes?

DILLON: Well it’s obvious from something you see at the end that she’s gotten over something but she hasn’t gotten over everything. And that’s how life is isn’t it? You might get better at something but there will always be problems, there will always be something else to challenge you. I didn’t want to give her an entirely happy ending.

MAUTNER: You don’t reveal who Nao ultimately ends up with either.

DILLON: It’s not important. The more important thing is her story. I thought it’s kind of nicer to leave it hanging. Do you know the film Broken Flowers? The Jim Jarmusch film. [Bill Murray] is looking for the woman who fathered his son. And in the end you don’t find out the thing you’ve been looking for. I like the idea that there’s something left hanging. There’s something for the reader to take part in. They can think who they would like it to be.

MAUTNER: You were talking about your brother’s influence on you in making comics. Do you feel competitive with him?

DILLON: When I was young and just boldly, precociously going to editors and showing them my work, I think they didn’t turn me away because they knew I was Steve’s brother. If I wasn’t his brother, they might have said, “Come back when you’re a bit better.” But they’d always be kind enough to entertain me when I went into their offices and bugged them. But my brother was always very conscious of not wanting there to be any nepotism, so he never helped out. I never did any work for Deadline until he stopped editing it. It was the next phase of the editors that came in that invited me to do some work. So I didn’t feel competitive, no. Not with him. In the early days of the Internet when Google was brand-new I’d Google my name and there was some quote that said, “Glyn Dillon, Steve Dillon’s less talented brother.”

MAUTNER: Ouch.

DILLON: I suppose that spurs me on a little bit, but I don’t feel direct competition with him. He’s lovely. We get on really well.

MAUTNER: Do you consult with each other? Did you consult with anyone while making Brown_?_

DILLON: No. Only my wife really. She was the sounding board. I took a few pages to Thought Bubble, one of the conventions in Leeds, at the very early stages, but not really, no.

MAUTNER: I’m curious what the comics scene is like in Britain these days. Right now we’re seeing this what seems like an eruption with SelfMadeHero and Nobrow and Blank Slate Books. For me, probably because I’m dense, it seems like it cropped up out of nowhere, and that can’t be the case. So I’m curious what your perception of the comics scene in Britain right now is like.

DILLON: It’s very different from when I was in comics before. I hadn’t been following the scene at all. I’d maybe buy the odd graphic novel now and again but I didn’t follow any comics on a regular basis, so when I got back into it I felt like I needed to catch up and I went to Thought Bubble in Leeds, which is the relatively new convention. And I started on Twitter and gotten to know a few artists on Twitter. That seems to be where the scene, if you can call it that, is. It came out of Twitter for me. I met people via that and then met them in real life at the convention.

DILLON: It’s very different from when I was in comics before. I hadn’t been following the scene at all. I’d maybe buy the odd graphic novel now and again but I didn’t follow any comics on a regular basis, so when I got back into it I felt like I needed to catch up and I went to Thought Bubble in Leeds, which is the relatively new convention. And I started on Twitter and gotten to know a few artists on Twitter. That seems to be where the scene, if you can call it that, is. It came out of Twitter for me. I met people via that and then met them in real life at the convention.

But I think just the fact that there are these three new publishers – there were no publishers to do that kind of personal work back in the early '90s. Deadline was a monthly magazine. There were no proper book publishers. So I think maybe it’s just a generation of people that got used to seeing Chris Ware, Dan Clowes, the Hernandez brothers, those kind of books have started to get into normal book shops, not just comic book shops. So there’s a generation of kids that grow up and see that as normal. It’s very much a comics world mixed with the book world. It’s not just a comic book arena.

MAUTNER: What’s it like working with SelfMadeHero?

DILLON: They’re lovely. The thing I like most is that they left me alone. As an object I’m really pleased with how it came out. I like the blocking on the book and the deboss on the hardcover and the double sided printing on the dust jacket.

MAUTNER: [Taking off the jacket] I didn’t even see that!

DILLON: I really wanted to do all that stuff. I wanted it to be a lovely object to have. And at no point did they ever say, ‘Oh no, we can’t afford to do that.’ They were up for doing whatever.

MAUTNER: What’s your plan from here on in? Do you see yourself doing more books like Brown_?_

DILLON: I have to go back and do storyboards. I need to earn some money.

MAUTNER: That’s the sad truth about comics, isn’t it?

DILLON: If only they paid as well as storyboarding. Hopefully I can continue doing comics but I have to go back and do a bit of that [other work]. If I come up with a big idea for a book I’ll just start doing it in my spare time. When I was doing comics before, the whole small press thing probably existed but I didn’t really know about it. But now I like the idea I can make my own comic in my spare time and print it out and keep coming to events like this. I really like that idea. That seems much more feasible now. I might do a bit of that and hopefully come up with an idea for a book.