Where Did the Internet Begin? (original) (raw)

The Room Where the Internet Was Born

An epic American road trip—to see “The Cloud” in all its strange manifestations—begins in an old lab at UCLA.

Sam Kronick

Starting a cross-country drive to New York in Los Angeles is pretty inconvenient, unless your cross-country drive is also a vision quest to see the Internet. More specifically, we'd been tasked with going to see “the cloud”—a term I've generally been loath to embrace, as I tend to think of it as a pernicious metaphor encouraging unrealistic collective fictions. Which, as someone who actively chooses to live in New York, is kind of how I imagine Los Angeles.

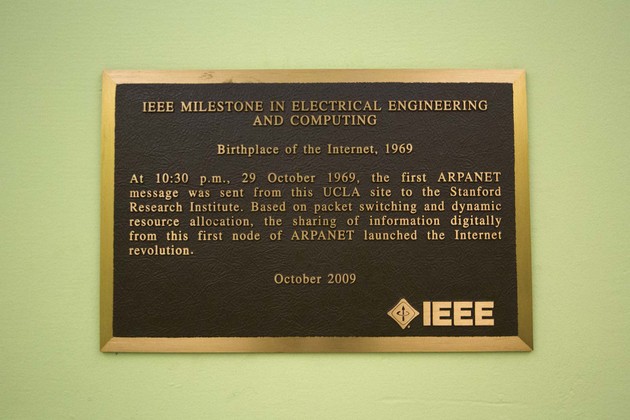

But we didn't come to L.A. just to ensure that this road trip had adequate Pynchonesque vibes. We came to L.A. because we wanted to start the drive where the cloud started—and we decided that meant going to where the Internet started, which, in turn, meant going down a rabbit hole of debated histories that, for better or worse, deposited us in room 3420 at the University of California, Los Angeles's Boetler Hall. This was the home of UCLA's Network Measurement Center, which, between 1969 and 1975, served as one of the first nodes of the ARPANET.

The problem that cloud computing seeks to solve isn't really all that radically different from the ones that led to the development of ARPANET. According to the National Institute of Standards and Technology, cloud computing is “a model for enabling ubiquitous, convenient, on-demand network access to a shared pool of configurable computing resources … that can be rapidly provisioned and released with minimal management effort or service-provider interaction.” That doesn't actually sound all that different from the objectives of time-sharing, a concept that emerged in the mid-1950s whose name is largely credited to the computer scientist John McCarthy.

Early computers were a really large, expensive, and intensively energy-consuming technology—which meant that they weren't particularly accessible to many people. Time-sharing was a way to allow multiple users to simultaneously access and use the same computer, bringing down the cost of access by having a larger pool of users and maximizing efficient use of the machines. Early time-sharing systems were first developed in the 1960s at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and eventually developed into for-profit “time service bureaus” like Tymshare.

ARPANET further expanded upon the principles of time sharing, initially hosting four network nodes at the Stanford Research Institute, UC Santa Barbara, the University of Utah, and UCLA. Watching The Heralds of Resource Sharing, a short documentary about the ARPANET, the dilemmas that they describe and created the ARPANET to solve don't seem entirely far removed from the ones that drive the use of cloud storage.

In 2011, UCLA's Kleinrock Center for Internet Studies decided to restore the room to its original appearance in the 1970s, or a reasonable approximation thereof. Most days of the year the room lies dormant, generally opened up for prospective-student tours and, apparently, people on vision quests who send emails asking for a tour. The room is actually only about half the size of its original dimensions, a carefully constructed diorama of artifacts and replicas of artifacts that were part of the original center.

Sam Kronick

The room is painted in the closest approximation of its color in archival photos, a pale industrial green that is somehow both soothing and sinister. It is the Muzak equivalent of the color green, a wall color that only could have been popular in the 1970s. Most of the period furniture was actually just taken out of UCLA's storage. Not all of the computer hardware from those days was kept in storage or considered historically relevant to preserve. The IMP is original, as is the first packet switch installed on the Arpanet, and the teletype. But the mainframe computer components are replicas, designed according to old specs.

In a strikingly accurate replica of the original IMP log (crafted by UCLA's Fowler Museum of Cultural History) on one of the room's period desks is a note taken at 10:30 p.m., 29 October, 1969—“talked to SRI, host to host.” In the note, there is no sense of wonder at this event—which marks the first message sent across the ARPANET, and the primary reason the room is now deemed hallowed ground.

Room 3240 reminded me of another telecommunications landmark I'd visited while on the road: the Golden Spike National Monument in Promontory Summit, Utah, where the first transcontinental railroad united in 1869. The monument features two replica steam-powered trains, maintained by National Parks Service employees, that perform the task of going up and down a small railroad track on a daily schedule.

Very little at the Golden Spike is from the original time. The actual spike is in a museum at Stanford University, the original trains long ago scrapped. No railroads run through Promontory Summit anymore—eventually the Lucin Cutoff and Salt Lake Causeway superseded the original route through Promontory. In 1942, the route was ceremoniously “unspiked” and its tracks ended up being subsumed in World War II's scrap-metal drives, viewed in its time with the same dull pragmatism that left Room 3240's furniture in storage.

Technology doesn't lend itself well to landmarking and memorializing, because when a tool stops working we don't archive it, we just stop using it. When we do commemorate, it is in search of a singularity where there may only be a series of convenient confluences, a statement of significance where there may only be a line in a log book.

* * *

I wanted to start this trip with some grounding in history (or, as it turns out, anxious historiography) because one of the most pernicious aspects of The Cloud as an everyday metaphor we live with is that it is ahistorical. Not so much as it is not of its time as it feels outside of time itself, placing past and present in a state of perpetual future-perfect, an accumulation of once-consecutive facts now ignoring all space-time distinctions (and yes, dear reader who appreciates a bad Nabokov reference, beyond which it snows, and the dusk deepens, and nobody really loves anybody).

But The Cloud, and the conditions that shape the way we live with it, had to come from somewhere. It's not a somewhere that can be seen as a coherent whole, but one that emerges in fragments, in particular sites: cornfields of the American midwest, remote beaches in California, unmarked buildings in Northern Virginia.

We left L.A. late, with warnings of flash floods in Arizona. For a few hours, we remained just beyond the storm, literally following clouds into the desert. It seemed like a pretty good omen.

About the Author

Ingrid Burrington is a writer based in New York. Her work has appeared in Quartz, The Nation, and the San Francisco Art Quarterly.