Pentagon blocking Guantánamo deals to return Shaker Aamer and other cleared detainees (original) (raw)

The Pentagon is blocking the return of UK permanent resident Shaker Aamer and two other longtime Guantánamo Bay detainees for whom the US Department of State has completed diplomatic deals to transfer home, the Guardian has learned.

American and UK diplomats reached an agreement in late 2013 for the return of Aamer, who has spent more than 13 years at the infamous detention facility without charge, according to multiple sources with knowledge of the understanding.

But even as the White House pledged to make his case a priority after a personal plea from David Cameron, Barack Obama’s defense secretaries have played what one official called “foot-dragging and process games” to let the deals languish.

Pentagon chief Ashton Carter, backed by powerful US military officers, has withheld support for sending Aamer back to the UK. The ongoing obstruction has left current and former US officials who consider the detainees a minimal threat seething, as they see it undermining relations with Britain and other foreign partners while subverting from the inside Obama’s long-stifled goal of closing the infamous detention facility.

Some consider the White House indecisive on Guantánamo issues, effectively enabling Pentagon intransigence ahead of the release of a long-awaited strategy for closing the facility before Obama’s presidency ends.

Two of the men being kept at Guantánamo were cleared by a 2010 government review, in which the Pentagon participated, that found them to pose little threat to US or allied national security. Aamer is among them.

Administration officials said the Pentagon has never formally opposed the transfers, an act of outright resistance to a high-profile presidential commitment that risks reprisal. The transfers have the backing of the US Justice Department, the State Department, the Department of Homeland Security and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

But since White House rules depend on full administration consensus, Aamer remains at Guantánamo until Carter and the Pentagon say otherwise.

By law, the US defense secretary must sign off on the transfers, which occur 30 days after the Pentagon chief’s signature. Chuck Hagel’s reluctance to closing Guantánamo contributed to his firing last year, but successor Carter has not proven any more pliable.

“Carter is worse,” said one official, who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss a topic of significant internal acrimony within the Obama administration.

The Pentagon opposition helps explain why Aamer has remained at Guantánamo despite bipartisan anger from the United States’ closest international ally. “A slap in the face is right,” one frustrated official said, agreeing with the characterization in a recent article by Labour MPs Jeremy Corbyn and Andy Slaughter along with conservative MPs David Davis and Andrew Mitchell.

US officials said they reached a deal with their British counterparts on transferring Aamer at a meeting in Washington in October 2013, subject to final approval from senior officials. The Pentagon has been the holdout.

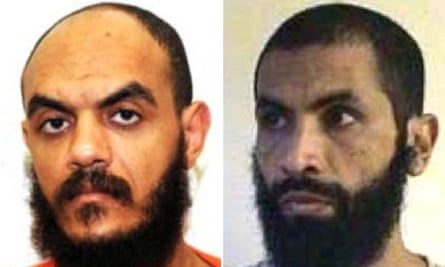

Abdul Shalabi, left, and Ahmed Ould Abdel Aziz. Photograph: Internet

The other two detainees are the Mauritanian Ahmed Ould Abdel Aziz and the Saudi Abdul Shalabi. The state department has deals in place with the three detainees’ home countries that still await Carter’s signature. US diplomats reached an agreement to transfer Abdel Aziz in fall 2013; Shalabi was cleared on 15 June by a quasi-parole hearing called a Periodic Review Board.

The Washington Post this week reported that Carter was positively inclined to transfer Aamer, raising hopes of his release. But the high-level meeting last month at which Carter expressed that sentiment was supposed to have been a forum to finalize decisions on transferring extant detainees, leaving other officials with the impression that Carter was continuing to stall while appearing cooperative.

The well of opposition to the transfers does not end with the defense secretary. Carter is supported by the staff of the outgoing chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Martin Dempsey, as well as the powerful General John Kelly, head of US southern command, which oversees Guantanamo.

Paul Lewis, whose high-profile appointment as Pentagon envoy for Guantánamo was touted as evidence of Obama’s commitment to shuttering the facility, is seen as marginalized and ineffective. An official called Lewis a “non-factor”.

“The building doesn’t want to do it,” the official said, referring to the Pentagon.

Brian McKeon, a senior Pentagon policy official, defended Lewis’ efficacy to the Guardian, citing his “bipartisan experience and unrivaled expertise” on Guantánamo matters gained from his prior stint as a congressional aide.

“Mr Lewis is integral to the process of ending detention operations at Guantánamo Bay. He works closely with the secretary and other high-level leaders in the defense department and throughout the interagency, as well as with our international partners and members of Congress,” McKeon said, adding that Lewis has “enabled President Obama and Secretary Carter to achieve significant progress towards their shared goal of closing the detention facility at Guantanamo Bay in a responsible manner”.

For years, the Defense Department has forced the other US agencies through a laborious process of requiring additional information about how the transfers of Aamer and Abdul Aziz will work, something officials outside the Pentagon consider a delaying tactic. Concern is mounting that the delays make it harder for US diplomats to convince other countries to accept Guantánamo detainees.

The White House is considered irresolute on Guantánamo, lacking the force or the desire to impose a coherent policy upon the bureaucracy. There is already longstanding bipartisan hostility in Congress to closing Guantánamo, but transferring the 52 remaining detainees whom the 2010 government review deemed minimal risks is the least controversial aspect.

“For those who are approved for transfer, the laws passed by Congress permit it and we should be moving forward with those promptly,” said Clifford Sloan, who until December served as the state department’s special envoy for closing the Guantánamo Bay detention center.

Far more difficult is the question of what to do with the 32 so-called “forever prisoners” whom the review recommended for continued detention without trial until the end of a “war on terrorism” that has no defined endpoint. A forthcoming strategy from the White House, as anticipated as it is delayed, must grapple with Congress’ legal ban on detaining them on US soil. There are 116 detainees currently at Guantánamo.

Aamer is one of its earliest detainees, arriving at the facility in February 2002 after his late 2001 capture by Afghan militiamen redeeming a US bounty. Shalabi precedes him by one month. Abdul Aziz joined them in October 2002.

A protester holds up a sign calling for the release of Shaker Aamer from Guantánamo during a demonstration in central London in 2010. Photograph: Leon Neal/AFP/Getty Images

In the UK, Aamer’s continued detention is a cause célèbre. In addition to the June “slap in the face” article, last month a politically diverse coalition of signatories ranging from London mayor Boris Johnson to Sting urged Obama to release Aamer as a method of restoring “America’s notion of itself and its international standing”.

Sloan warned that Obama’s administration was running out of time to fulfill his promise of shuttering Guantánamo and urged the acceleration of the transfers of approved detainees.

“Any month where we’re not seeing significant numbers of transfers undermines the president’s policy and is unfair to the individuals affected,” Sloan said.

Clive Stafford Smith, one of Aamer’s US attorneys with the human rights group Reprieve, said “it it is time for the secretary of defense to stop playing these furtive games and put up or shut up”.

“If there is one thing that is worse than indefinite, arbitrary detention without trial,” he said, “it is indefinite, arbitrary detention without trial when 99% of the people on both sides think you should be released but one percent vetoes fairness secretly, without giving reasons, either to Shaker or to the prime minister of Great Britain.”

A spokeswoman for the UK Foreign Office said the Aamer case “remains a high priority for the UK government”.

“We continue to make clear to the US that we want him released and returned to the UK as a matter of urgency,” said the spokeswoman.

Henrietta Levin, a spokeswoman for the US Department of Defense, said she did not have a timetable for when select detainees might be released from Guantánamo.

“However,” she said in a statement, “the Defense Department is committed to reducing the detainee population and to closing the detention facility. We recognize the importance that our British allies have placed on resolving the Shaker Aamer case, and accordingly, we have made this case a priority.”