William Maxwell, The Art of Fiction No. 71 (original) (raw)

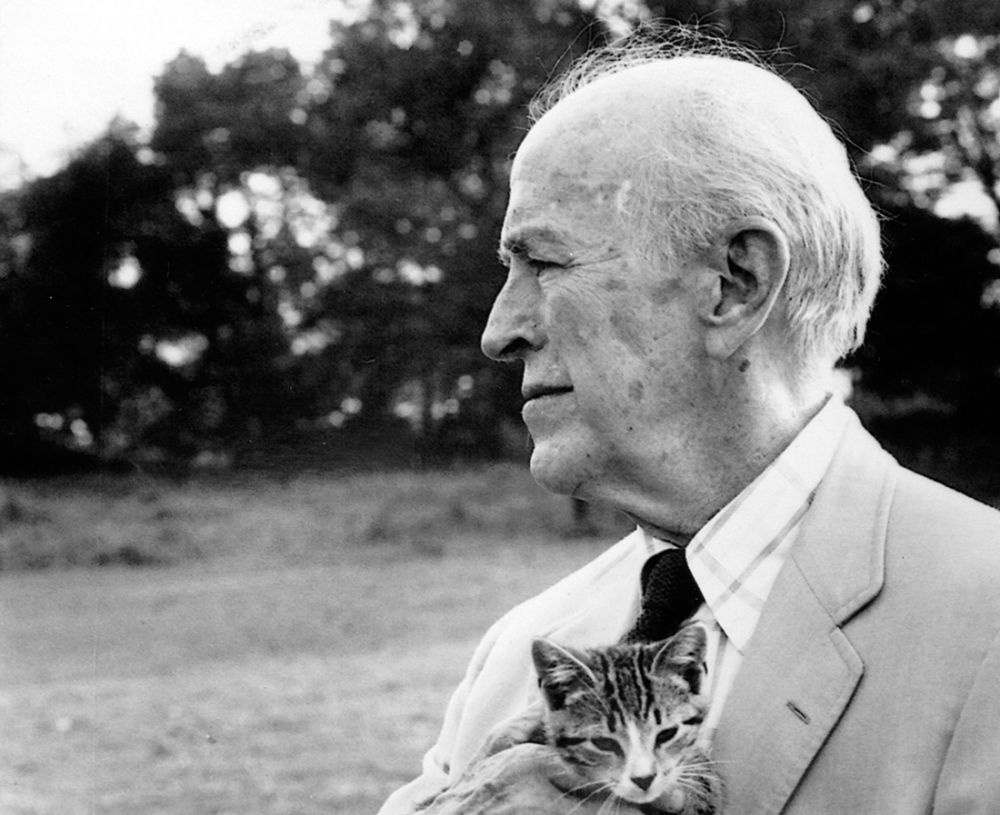

Photograph Brookie Maxwell

Photograph Brookie Maxwell

William Maxwell was interviewed in his East Side New York apartment. He wore a tie and blazer for the occasion. A tall, spare man, he sat on the edge of a low sofa, his knees nearly touching his chin. Twice he rose and went to the walnut bookcase, once for Virginia Woolf’s Between the Acts, and then for Eliot’s Four Quartets, which he studied patiently for the lines he needed. At the end of the living room, two large windows looked out on the street, eight floors below, where one could see the morning traffic, but not hear it. The spacious room was furnished austerely—two vases of flowers stood on the mantel, a piano occupied one corner. The decor did not suggest Maxwell’s profession. The rapture with which he recited Eliot did.

One of his colleagues at The New Yorker, Brendan Gill, has supplied the following report on his friend:

“In this interview William Maxwell at one juncture urges that the subject under discussion veer away from The New Yorker, on the grounds that the magazine has been almost done to death, in one book or another. No doubt a book that I once wrote is one of the death-dealing volumes that Maxwell has in mind, but no matter—let me offer a brief quotation from my Here at The New Yorker (a title suggested, by the way, by the editor of the magazine, William Shawn; I would never have dared to propose it on my own):

“One day in my office I was showing Maxwell a Roman coin that I had purchased at Gimbels. With thousands of similar coins, it had been buried in the sands of Egypt by Ptolemy’s army paymaster, in order to keep it from falling into the hands of the rapidly approaching Caesar. Maxwell jiggled the coin in his palm. “The odds,” he said, “are on objects.”

“True enough, but since Maxwell made the remark well over thirty years ago and since he and I are both in rude health and are evidently convinced that we have outwitted the need ever to die, we may be said to be doing not so badly, either as objects or subjects. And though Maxwell will enter history as a distinguished American author of the middle years of the twentieth century, he will also enter it in the reminiscences of many of his fellow authors as an exceptionally sympathetic and adroit editor. When I first met him, forty-five years ago, he was serving as Katharine White’s assistant, but he looked so young and so readily abashable that I mistook him for an office boy. I was right about his being young; I was wrong about his being abashable. He has a gentle voice to match his seemingly gentle heart, and yet I was to discover that on some level of his being he is as tough as nails. Maxwell said once of Shawn that he combines the best features of Napoleon and Saint Francis of Assisi; it is often the case when one makes such a comment about an associate that it will prove, at bottom, autobiographical. Unlike Shawn, Maxwell has been a joiner of organizations and has been happy in the acceptance of honors from the hands of his peers; at the same time, he is a loner. If he is a clubman, he is a clubman who eats and drinks by himself. Dr. Johnson would have stared askance at him, not in the least to Maxwell’s dismay.

“Over the years, how much Maxwell taught me about the art that I was trying to master and that was forever turning out to be more difficult than I had expected! How reluctant he was to reject a piece until every means of salvaging it had been explored! For a long time, Maxwell and I occupied adjoining offices in the squalid rabbit warren of The New Yorker; now and again in those days I would hear the faint, mouse-in-the-wainscot rustle of a note being slipped under my door. Opening the note, I would encounter five or six hastily typed words from Maxwell, in praise of something I had written. Snobbish as it is sure to sound, at The New Yorker we write not so much for readers out in the world as for one another, and it has always been for Shawn and Maxwell and Mitchell and Hamburger and the rest of my colleagues that I have written; on the occasions when a note from Maxwell appeared under my door, I felt ten feet tall and befuddled with joy.”

INTERVIEWER

So Long, See You Tomorrow comes nineteen years after your previous novel. Why this gap?

WILLIAM MAXWELL

Nothing but being an editor probably, and working on other people’s work. Which interested me very much. I had marvelous writers to work with. Quite a lot of me was satisfied just to be working with what they wrote. Besides, I write terribly slowly. The story “Over by the River” was started when the children were small and my older daughter was twenty when I finished it—it took over ten years. Undoubtedly if I knew exactly what I was doing, things would go faster, but if I saw the whole unwritten novel stretching out before me, chapter by chapter, like a landscape, I know I would put it aside in favor of something more uncertain—material that had a natural form that it was up to me to discover. So I never work from an outline. In 1948 we came home from France and I walked into the house, sat down at the typewriter with my hat still on my head, and wrote a page, a sort of rough statement of the book I meant to write, which I then thumbtacked to a shelf and didn’t look at again until it was finished. To my surprise everything I had managed to do in the novel was on that page. But in general the thing creeps along slowly, like a mole in the dark.

With So Long, See You Tomorrow I felt that in this century the first-person narrator has to be a character and not just a narrative device. So I used myself as the “I” and the result was two stories, my own and Cletus Smith’s, and I knew they had to be structurally combined, but how? One day I was in our house in Westchester County, and I was sitting on the side of the bed putting my shoes on, half stupefied after a nap and thinking, If I sit on the edge of the bed I will ruin the mattress, when my attention was caught by a book. I opened it and read part of a long letter from Giacometti to Matisse describing how he came to do a certain piece of sculpture—_Palace at 4 a.m._—it’s in the Museum of Modern Art—and I said, “There’s my novel!” It was as simple as that. But I didn’t know until that moment whether the book would work out or not.

INTERVIEWER

Much of your work seems to some extent autobiographical. Is autobiography just the raw material for fiction, or does it have a place in a novel or a story as a finished product?

MAXWELL

True autobiography is very different from anything I’ve ever written. Edmund Gosse’s Father and Son has a candor that comes from the intention of the writer to hand over his life. If the writer is really candid then it’s good autobiography, and if he’s not, then it’s nothing at all. I don’t feel that my stories, though they may appear to be autobiographical, represent an intention to hand over the whole of my life. They are fragments in which I am a character along with all the others. They’re written from a considerable distance. I never feel exposed by them in any way.

As I get older I put more trust in what happened, which has a profound meaning if you can get at it. But what you invent is important too. Flaubert said that whatever you invent is true, even though you may not understand what the truth of it is.

When I reread The Folded Leaf, the parts I invented seem so real to me that I have quite a lot of trouble convincing myself they never actually happened.

INTERVIEWER

How do you apply that to character? What is the process involved in making a real person into a fictional one?

MAXWELL

In The Folded Leaf, the man who owned the antique shop bore a considerable resemblance to John Mosher, who was the movie critic at The New Yorker. He was a terribly amusing man whom I was very fond of. Nothing that John ever said is in that book, but I felt a certain security at the beginning in the identification. Then I forgot about Mosher entirely, because the person in the book sprang to life. I knew what he would do in a given situation, and what he would say . . . that sudden confidence that makes the characters suddenly belong to you, and not just be borrowed from real life. Then you reach a further point where the character doesn’t belong to you any longer, because he’s taken off; there’s nothing you can do but put down what he does and says. That’s the best of all.

INTERVIEWER

Virginia Woolf was an influence in your early work, wasn’t she?

MAXWELL

Oh, yes. She’s there. Everybody’s there. My first novel, Bright Center of Heaven, is a compendium of all the writers I loved and admired. In a symposium at Smith College, Saul Bellow said something that describes it to perfection. He said, “A writer is a reader who is moved to emulation.” What I wrote when I was very young had some of the characteristic qualities of every writer I had any feeling for. It takes a while before that admiration sinks back and becomes unconscious. The writers stay with you for the rest of your life. But at least they don’t intrude and become visible to the reader.

INTERVIEWER

Well, all young writers have to come to terms with their literary fathers and mothers.

MAXWELL

And think what To the Lighthouse meant to me, how close Mrs. Ramsay is to my own idea of my mother . . . both of them gone, both leaving the family unable to navigate very well. It couldn’t have failed to have a profound effect on me.

INTERVIEWER

What exactly is the force that makes you a writer?

MAXWELL

Your question reminds me of something. I was having lunch with Pete Lemay, who was the publicity director at Knopf and is now a playwright, and he said that he had known Willa Cather when he was a young man. I asked what she was like and he told me at some length. It wasn’t what I had assumed and because I was surprised I said, “Whatever made her a writer, do you suppose?” and he said, “Why, what makes anyone a writer—deprivation, of course.” And then he begged my pardon. But I do think it’s deprivation that makes people writers, if they have it in them to be a writer. With Ancestors I thought I was writing an account of my Campbellite forebears and the deprivation didn’t even show up in the first draft, but the high point of the book emotionally turned out to be the two chapters dealing with our family life before and after my mother’s death in the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918. I had written about this before, in They Came Like Swallows and again in The Folded Leaf, where it is fictionalized out of recognition; but there was always something untold, something I remembered from that time. I meant So Long, See You Tomorrow to be the story of somebody else’s tragedy but the narrative weight is evenly distributed between the rifle shot on the first page and my mother’s absence. Now I have nothing more to say about the death of my mother, I think, forever. But it was a motivating force in four books. If my mother turns up again I will be astonished. I may even tell her to go away. But I do not think it will be necessary.

INTERVIEWER

But to what extent can writing recover what you lose in life?

MAXWELL

If you get it all down there’s a serenity that is marvelous. I don’t mean just getting the facts down, but the degree of imagination you bring to it. Autobiography is simply the facts, but imagination is the landscape in which the facts take place, and the way that everything moves. When I went to France the first time I promptly fell in love with it. I was forty years old. My wife had been there as a child, and we were always looking for two things she remembered but didn’t know where they were: a church at the end of a streetcar line and a château with a green lawn in front of it. We came home after four months because our money ran out. I couldn’t bear not to be there, and so I began to write a novel about it. And for ten years I lived perfectly happily in France, remembering every town we passed through, every street we were ever on, everything that ever happened, including the weather. Of course, I was faced with the extremely difficult problem of how all this self-indulgence could be made into a novel.