The Batman Chronology ProjectThe Batman Chronology Project (original) (raw)

BATMAN AND THE ART OF CONTINUITY MAINTENANCE

_______________________________

The Batman Chronology Project is a study of serialized storytelling in superhero comics. More specifically, it tracks the narrative continuity of DC Comics via the lens of Batman, plotting his appearances into detailed timelines. To most folks, simple questions arise: “Doesn’t one just read the comics in the order they are published? Why does there need to be a project dedicated to ordering comics? If it is so difficult to figure out a reading order, surely there must be a lot of similar projects online, right?” Ultimately, we get to the bigger question: “Why is this site necessary?”

These questions (which I will answer, don’t worry!) speak to something broader than just Batman (we’ll get to Batman in a minute, don’t worry!)—they speak to the complexity of superhero comics in general. Beyond the already layered intricacy of writing and reading sequential art, the very nature of superhero comics is unique compared to other forms of media. When you read (or create) serialized superhero comic book narratives, you are engaging in a perceptive (or artistic) process that is unlike any other. This site, using Batman as a primary case study, serves to analyze and catalogue this phenomenon.

A typical comic shop rack.

The narrative complexity of mainstream comics consists primarily of a few key things. First, as Douglas Wolk says in his book All of the Marvels (2021), superhero universes exist in comics as “a cluster of overlapping serials” that have “a different relationship with time and sequence than most kinds of narrative art.” This “cluster” is comprised of vast collections of interconnected serialized fiction—authored by hundreds of different people, including writers, pencilers, colorists, inkers, letterers, editors, publishers, and more—over the span of decades. Beyond this (and because of this), much of the superhero genre is hermeneutic—open to both reader interoperation and authorial interpretation of previous authorship. Every week, dozens of new titles come out continuing the story from the previous week’s batch of titles. And all of these titles—week to week, month to month, and so on—tell an ongoing über-story in which the events and characters of said titles all exist in the same shared world, directly influencing each other. Media scholars have also referred to the über-story as a mega-text or aggregate narrative (Jim Collins), macro-structure (Marie-Laure Ryan), or fiction network (Jason Craft). The Big Two are DC and Marvel, having combined to regularly garner over 70% of the annual market share since the 1990s. (Image, Dark Horse, and IDW, along with small indie publishers, account for the rest of the share.) The Big Two each release dozens of new comics per week. In 2017, according to The Atlantic, “Marvel [was publishing] around 75 ongoing [monthly] series, along with miniseries and single-issue specials. DC [was publishing] around 50 [monthly] ongoing series.” According to Comichron, in 2019, Marvel released 1,191 single issues while DC released 890. That’s a lot of material, and the Big Two don’t tell you in what order to read them or how to organize them. To be clear, Marvel and DC do publish trade paperbacks and their issues are all numbered and can be read in some sort of an order. But when it comes to stitching every title together to make the über-story that tells the whole tale, that is not a task that either company really gets bogged down in. If we look solely at DC, for example, we are talking about literally hundreds of creators working together to create a “shared universe”—essentially one single unified story. How can all these titles (and creators) possibly exist and function cohesively? How can there be a coherent story, both visually and narratively? Holistically, the comics form a puzzle and it’s how the pieces fit together that really interests me.

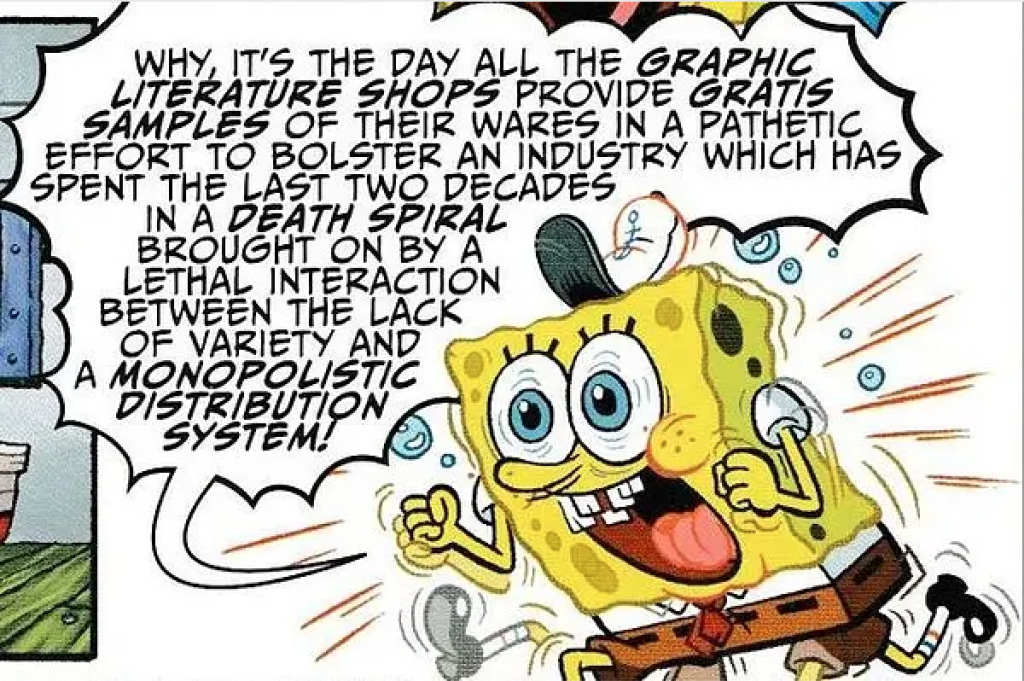

Spongebob Drops a Pipe Bomb

But before moving on, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the commercial effect upon story. Most purely narrative-based approaches to comics studies don’t address the industrial processes that determine how comics texts get made. Because the Batman Chronology Project is a narrative-based study, and specifically not a media industry study, it won’t often touch upon the commerce/merchandising side of things. However, one of the failings of any narratological study is to stray too far from identifying indelible industrial factors that contribute to story. As such, the Batman Chronology Project will touch upon these connections when appropriate. When I say “DC” in this proem, I’m referring to the beast that is “DC the company.” Same goes for “Marvel.” (DC is owned by Warner Bros Discovery. Marvel is owned by the Walt Disney Company.) Without Warner Bros Discovery, Disney, and other conglomerates, our favorite characters and stories would not exist in the forms they do today. Is this good? Is this bad? It’s an issue that increases in complexity as you peel back the layers. We cannot deny that Big Business has a long-documented tradition of screwing over some writers, and artists. (Superman creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster spent most of their lives in the poorhouse, fighting for a share of their character’s riches. Bill Finger went decades without acknowledgement that he co-invented Batman.) Most creators still don’t own their own creations, although a balance of creator-owned, co-owned, and work-for-hire models has led to better financial compensation for creators within the contemporary comics ecosystem. Nevertheless, when it comes to precious intellectual property, corporations have a long history of throwing their weight around to extend copyright, and this still goes on today with intense lobbying and litigation. Big Business also played its dirty hand in the form of the gross Diamond Comics print distribution monopoly, which existed from the mid 1990s through the early 2020s before being broken up by a combination of an augmented digital market, DC’s move to creating its own distributor (Lunar), and both Marvel and IDW switching to publishing giant Penguin Random House. Ethics in the comic book industry isn’t something that I will tackle with regularity on this site, but it should be kept in our minds as consumers and fans. All superhero comics, including Batman books, are the products of many different creative minds, but it is the conservative or neoliberal committee of corporate bigwigs, marketing execs, publishers, and editors that control the characters and the worlds in which they live—even if most of the time the committee has contributed little or nothing towards either. Thus, from a narratological perspective, strong (i.e. accessible and unbroken) continuity or innovative story development are tough things to achieve in a capitalist money-focused market. The hierarchical dynamics of the industry directly affect how story, character, and continuity are shaped. For example, as eloquently extrapolated by Alisa Perren and Gregory Steirer in The American Comic Book Industry and Hollywood, throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, comics would primarily be purchased at newsstands—and because you couldn’t guarantee that a given title would appear each month at the same retailer, issues couldn’t be too serialized or contain impenetrable continuity-driven narrative. After all, readers had to be able to follow the story even if they missed a few issues. “By circumventing newsstand distribution entirely,” as Proctor explains in Reboot Culture (2023), “publishers would ensure comics reached a certain audience made up of super-readers, collectors, and speculators, rather than the childhood [and mainstream] audiences that had been their primary consumer market for decades.” As the direct market model of distribution, speculation, collection, overproduction, boutique shop inclusivity, IP farming, and mismanaged crossover event-style cash grabs all became more commonplace, superhero comics began to see more tropes of serialization, including more detailed world-building and cumbersome continuity tailored to the niche fan. There’s obviously way more to say about this topic, but it’s likely better served in a different forum. In the end, no matter what, I love superhero comics and hope they will continue to evolve for the better.

Batman Cover to Cover: The Greatest Comic Book Covers of the Dark Knight (2005)

But why Batman? Why is he so important? Well, he’s not just an awesome character. He’s quite popular, in case you didn’t know—he shows up in almost every DC title at some point or another. Batman—along with Superman, and to a lesser extent Wonder Woman—is a primary lens through which DC Comics has been able to tell a consistent narrative for the past 80 years-plus. In the DC Universe, everything kind of revolves around the Holy Trinity of Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman. Therefore, sticking with the appearances of one of the Trinity—in our case, Batman—allows for the easiest determination of character age, passage of time, event placement, where things need to be rearranged, how things come together, or how things fail to come together for the entire DC Universe. Of course, a ton of variables have to be considered and the process gets complicated. This is the reason why there are so few attempts at what I’ve done. The few that exist—in dedicated areas of the Internet and in a few rare books—have either been quickly abandoned or left incomplete. Because Batman’s past is so rich, most evaluations or analyses from the narratological perspective of serialization have been less than successful. I’m sort of a masochist for continuing such a Sisyphean project with such rigorous diligence! But I do so because of a desire to prove certain theses: one, continuity equals congruity (meaning that, contrary to what a lot of folks think, continuity isn’t supposed to over-complicate or make texts feel exclusive—it actually helps us understand narrative more easily); two, serialized multi-authored narratives utilize truly unique forms of storytelling; and, three, a cohesive superhero universe is the result of a collaborative interpretive process undertaken by both creators and readers alike. By focusing on the media archeology of fictional canon and reboots, the Batman Chronology Project has been able to verify this list and remain the preeminent source of comic book continuity information on the web.

_______________________________

_______________________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________

Please click on the following link to continue reading the next part: Fictional Canon: What Counts?

_______________________________

_______________________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________

ABOUT THE SITE CREATOR/PROJECT MANAGER:

Collin Colsher, creator of the Batman Chronology Project, is a writer and comic book historian that currently lives in Philadelphia. He has lectured at various universities, libraries, and book fairs. Collin has also served on the jury for the Lynd Ward Graphic Novel Prize, which is sponsored by the US Library of Congress.

_______________________________

_______________________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________