About Urasenke Chado (original) (raw)

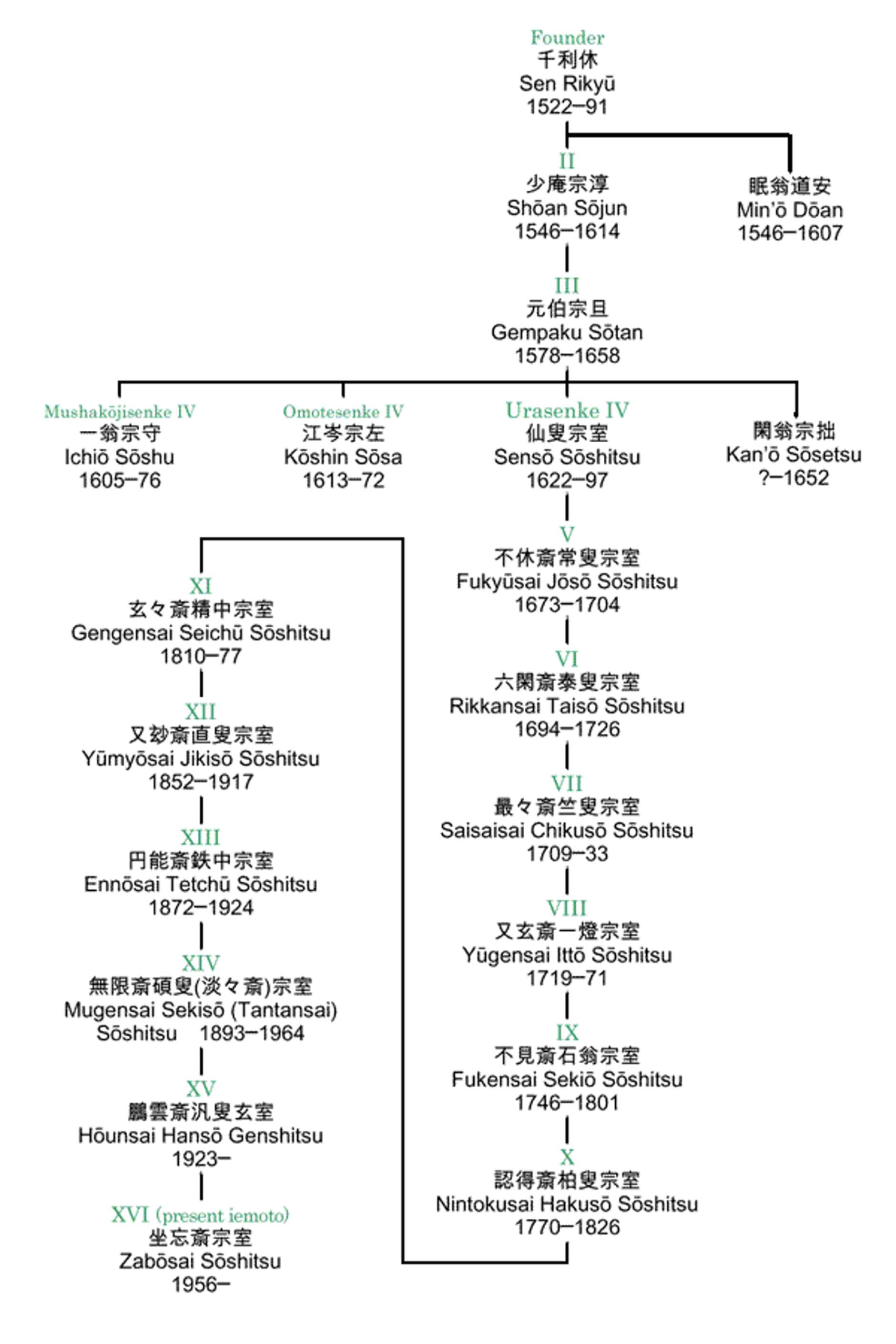

Family Lineage

SEN Rikyu (1522-91)

Rikyu, the man who perfected the style of chanoyu based on the wabi aesthetic and elevated chanoyu into a ‘way’ — the way of tea, or chado — was born in Sakai, located in present-day Osaka Prefecture. His father was a warehouse owner named Tanaka Yohe’e, and Rikyu’s childhood name was Yoshiro.

In his youth, he studied chanoyu under Kitamuki Dochin, who taught him the shoin style of tea service which had been developed at the Higashiyama villa of Shogun ASHIKAGA Yoshimasa. He received the name Soeki from the priest Dairin Soto of Nanshuji temple in Sakai, and, when he was nineteen, began to study chanoyu under Takeno Joo, an early proponent of the wabi aesthetic in chanoyu.

Soeki rose to the position of chanoyu expert for the hegemon ODA Nobunaga, and, after Nobunaga’s death, entered the service of Nobunaga’s successor, TOYOTOMI Hideyoshi. In 1585, Soeki assisted Hideyoshi at a tea gathering for Emperor Ogimachi held at the Imperial Palace. On that occasion, the emperor bestowed upon him the Buddhist lay name and title, Rikyu Koji.

It was during his late years that Rikyu brought chanoyu to its perfection, transforming it into a profound ‘way’ or approach to life. He began to use very tiny, rustic tea rooms, such as the two-tatami tea room named Taian, which can be seen today at Myokian temple in Yamazaki, a suburb of Kyoto city. His wabi philosophy and creativity found expression in his development and use of Raku tea bowls, his creation of flower containers, teascoops, and lid rests made of bamboo, and his use of ordinary objects from everyday life, which he adapted and used in new ways for chado.

Although Rikyu had been one of Hideyoshi’s closest confidants, because of crucial differences of opinion and other reasons which remain uncertain, Hideyoshi ordered him to commit ritual suicide. Rikyu carried out this order on the 28th day of the 2nd month, 1591, at his Jurakudai residence in Kyoto. He was seventy years old, as determined from his farewell gatha and poem which begins as follows: “A life of seventy years, strength spent to the very last….”

Rikyu’s grave is located at Jukoin temple within the Daitokuji compound in Kyoto, as are the ancestral graves of all the Kyoto Sen family. His posthumous Buddhist name is Fushin’an Rikyu Soeki Koji. The memorial for Rikyu is annually observed at Urasenke on March 28.

2nd Generation

Shoan Sojun (1546-1614)

Shoan was Rikyu’s adopted son; his mother was Rikyu’s second wife, Soon, and his wife was Rikyu’s daughter, Okame. After Rikyu’s death by order of Hideyoshi, Shoan took refuge in Aizu-Wakamatsu with Gamo Ujisato, one of Rikyu’s disciples. Through the intervention of Gamo and TOKUGAWA Ieyasu, who later became the first Tokugawa shogun, Hideyoshi allowed Shoan to return home to Kyoto. Shoan moved Rikyu’s tea house, Fushin’an, to its present location on Ogawa street.

Shoan remained the head of the family for only a short period before passing the position to his son, Sotan, because he believed that Rikyu’s direct descendant should head the household. Although his era was short, Shoan helped to protect Rikyu’s chanoyu ideals at a crucial period for the Sen family.

3rd Generation

Gempaku Sotan (1578-1658)

Rikyu’s grandson, Shuri, son of Shoan and Okame, was born in Sakai on the 1st day of the 1st month, 1578. He began his Zen training at the age of eleven under the priest Shun’oku Soen, head priest of Sangen’in at Daitokuji temple in Kyoto, where he became known by the name Sotan. Later in life, he also used the names Gempaku, Genshuku, Totsutotsusai, and Kan’un.

Sotan became the head of the Sen household in 1596, at the age of eighteen, when his father, Shoan, retired. He had two sons, Sosetsu and Soshu, by his first wife, and two more sons, Sosa and Senso, by his second wife, Soken, a former lady-in-waiting of Empress Tofukumon’in.

Although Sotan shunned public office, he was an important cultural figure of his time, and was well acquainted with many members of the cultural elite, including the talented calligrapher, potter, and sword appraiser HON’AMI Koetsu, and the important patron of the arts, Empress Tofukumon’in, who was the daughter of Shogun TOKUGAWA Hidetada and wife of Emperor Go-Mizuno’o.

Sotan is credited with playing a key role in the transmission of Rikyu’s ideals of chado; its survival to the present day is thought to be due in large part to his efforts. Sotan lived an austere, refined life based on his belief that the essence of chado and Zen are the same. His simple tea implements reflect his deep wabi philosophy, but he also designed a few gorgeous pieces which reflect the spirit of the exuberant Kan’ei period and his relationship to the imperial court.

In 1646, Sotan retired, and Sosa became the head of the family. At the back of the property, Sotan built a small tea hut, Konnichian. Later, he also built the Yuin and Kan’untei tea rooms, creating a compound separated from the main house. Sotan died in 1658, at the age of eighty-one. His memorial is annually observed at Urasenke on November 19.

4th Generation

Senso Soshitsu (1622-97)

Sotan’s fourth son, Senso, inherited the property containing the Konnichian tea hut, where he established the household which later became referred to as the Urasenke as distinguished from the household headed by Sotan’s third son, Sosa, referred to as the Omotesenke. This was during the peaceful and culturally effervescent Genroku period. He served as chado magistrate for MAEDA Toshitsune, lord of Kaga (present-day Ishikawa and Toyama Prefectures), and helped to establish a flourishing tea culture in the region. Senso took the potter Chozaemon, who worked under the 4th generation in the Raku line, Ichinyu, to Kaga, where Chozaemon established the Ohi kiln to produce tea ceramics. Senso also encouraged MIYAZAKI Kanchi to establish a foundry to cast tea kettles there.

In the early 1670s, his brothers Sosa and Soshu, heads of Omotesenke and Mushakojisenke, respectively, passed away, leaving him the sole elder of the three families. In that capacity, he held the important thirteenth memorial anniversary for his father and one-hundredth anniversary for Rikyu.

5th Generation

Fukyusai Joso Soshitsu (1673-1704)

Senso’s first son and successor is generally known by his names Fukyusai Joso. He inherited his father’s position as chado magistrate for the Kaga Maeda daimyo family, headquartered at Kanazawa Castle, and also became head of chanoyu affairs for the Iyo Hisamatsu daimyo family, who occupied Matsuyama Castle (in present-day Ehime Prefecture). After his father’s death, he used the name Soshitsu that his father had used as a teacher of chado, establishing the tradition for the head master of the Urasenke chado tradition to use that name. Although he died at the age of thirty-two, having been the head of Urasenke for only seven years, he left behind a number of outstanding tea implements of his own creation or design.

6th Generation

Rikkansai Taiso Soshitsu (1694-1726)

The sixth head of Urasenke is generally known by his name Rikkansai. Because his father passed away at an early age, he received his training from Kakukakusai Genso, the sixth head of Omotesenke. Carrying on his father’s appointments, Rikkansai served both the Maeda and Hisamatsu clans.

Rikkansai was well versed in the Chinese classics, noh, and kyogen, and was skilled in calligraphy and making tea bowls. Owing largely to the patronage of his wealthy disciples, he developed a highly-refined artistic sense. Sadly, however, he died at the age of thirty-three.

7th Generation

Saisaisai Chikuso Soshitsu (1709-33)

After Rikkansai’s untimely death, the seventeen-year-old second son of Kakukakusai Genso of Omotesenke was pressed into service to become the seventh head of Urasenke, known as Chikuso. Rikkansai’s mother and Genso looked after him, and he also received guidance from his older brother, who later became the seventh generation head master of Omotesenke, Joshinsai. Unfortunately, Chikuso died at the age of twenty-five, without having married.

8th Generation

Yugensai Itto Soshitsu (1719-71)

Left without an heir, the Urasenke household again looked to the Omotesenke house for a successor. Chikuso’s fourteen-year-old brother, Toichiro, was selected to become the eighth generation head of Urasenke, who was called Yugensai Itto. With his older brother Joshinsai, Itto underwent Zen training at Daitokuji temple under the guidance of the priests Daishin Gito, Dairyu Sojo, and Mugaku Soen. Together, the brothers created the shichijishiki, “seven training exercises,” as a means to reemphasize chanoyu’s spiritual aspect.

Itto created many tea implements and wrote the treatise, Hama no Masago [Sand on the Beach]. He served the Hisamatsu clan and also the Hachisuka clan of Awa (present-day Tokushima). Also he helped to establish the Sen tradition in Edo and encouraged the expansion of the practice of chanoyu by sending a disciple, KANO Soboku, to Osaka and another disciple, HAYAMI Sotatsu, to Okayama.

9th Generation

Fukensai Sekio Soshitsu (1746-1801)

The ninth generation in the Urasenke line is known as Fukensai Sekio. His major accomplishments were to restore the Urasenke property after the great fire of 1788 and to hold the bicentennial memorial observance for Rikyu in 1790. He had the statue of Rikyu, which was damaged in the fire, restored and rededicated by the priest Mugaku of Daitokuji in time for the memorial.

Fukensai worked diligently to counteract the shift of the center of culture from Kyoto to Edo. He lived to the age of fifty-five. His first son became the tenth generation head of Urasenke, Nintokusai, and his third son became the sixth head of Mushakojisenke, Kokosai.

10th Generation

Nintokusai Hakuso Soshitsu (1770-1826)

Fukensai’s eldest son, generally known as Nintokusai, became the tenth in the Urasenke line at the age of thirty-four. Nintokusai’s first son died unexpectedly in 1811, and although he had five other sons, they all died before reaching adulthood. Both his wife, Shoshitsu Soko, and daughter Teruko were serious practitioners of chado. Nintokusai was known as a strict father and teacher.

11th Generation

Gengensai Seichu Soshitsu (1810-77)

Gengensai lived during the years leading into the Meiji Era (1868-1912), a time of dramatic political and cultural change in Japan. This turbulent period saw the collapse of the Tokugawa Shogunate, the move of the emperor from Kyoto to the new capital, Tokyo (until then called Edo), Japan’s all-out adoption of Western civilization, and the country’s development into a modern state. Amid these circumstances, his major achievements included his success in convincing the new Meiji Government that it should officially recognize chado as a serious cultural and spiritual pursuit. This was when the Government was about to classify chado as a mere form of recreation. Gengensai is also credited as the originator of the ryurei style of chanoyu, which employs tables and stools. As for Urasenke itself, on the occasion of the 250th memorial for Sen Rikyu, he had the Totsutsusai, Dairo-no-ma, Hosensai, and Ryuseiken rooms added to the Konnichian compound, and also built the Kabutomon “Helmet Gate,” which became a symbol of the Urasenke head house. Because of his success in maintaining the vitality of chado in the new age, he is often referred to as the Father of the Restoration of Chado.

This particularly prominent figure in the Urasenke line, and in chanoyu history altogether, was the adopted heir of Nintokusai. His natural father was the 7th-generation head of the Ogyu Matsudaira family, a branch of one of the original Matsudaira lineages from which evolved the Tokugawa family. He was adopted by Nintokusai when he was nine years old and Nintokusai, whose only surviving offspring were girls, was already fifty. Nintokusai, taking into account the daimyo-family background of his new adopted son, saw to it that the boy was educated in the various fields of textbook learning of the time, as well as poetry, music, and other traditional cultural refinements. Nintokusai passed away seven years later, and thus Gengensai became the head of Urasenke when he was only sixteen.

As the family head, he continued the family’s hereditary posts as chanoyu magistrate for the Kaga Maeda daimyo family, headquartered at Kanazawa Castle, and the Iyo Hisamatsu daimyo family, who occupied Matsuyama Castle. Also, one of his brothers had become the adopted heir of the 10th-generation head of the Watanabe family which served as advisors to the Owari Tokugawa family, one of the three main branches of the shogunal Tokugawa family. Owing to this connection, Gengensai received the patronage of the 12th-generation head of the Owari Tokugawa family, headquartered at Nagoya Castle. On occasion, he also served tea to members of the imperial family, and furthermore, he was closely acquainted with many influential townspeople. Between Gengensai and Nintokusai’s daughter, who Gengensai took as his bride, there was born one boy. Tragically, however, the boy died at the age of sixteen. Consequently, when Gengensai was past sixty, he had his daughter marry a young man who would be his successor.

12th Generation

Yumyosai Jikiso Soshitsu (1852-1917)

Yumyosai was born as the second son of the head of the prominent Suminokura family of Kyoto. He married Gengensai’s daughter Yukako in 1871, when he was nineteen years old. This was just when the new government reforms were being put into effect and, among other things, the daimyo were displaced and their domains made into prefectures, and schooling became available to the masses, men and women alike. For Urasenke, the reforms had a devastating impact, as the family lost the stipends it had traditionally received from the daimyo families whom it had served through the generations as chanoyu magistrate. Amid this dark era, in 1885 Yumyosai, at the age of thirty-seven, turned the headship of the house over to his eldest son and retired to Myokian temple in Yamazaki. Yukako, who is known as Shinseiin, worked actively to have chado included in the curriculum of the newly established girls’ secondary schools.

13th Generation

Ennosai Tetchu Soshitsu (1872-1924)

The son of Yumyosai and Yukako, Komakichi, became the head of Urasenke at the age of twelve. He is generally known as Ennosai, and also had the names Tetchu and Tairyu. After his marriage in 1889, he and his wife traveled to Tokyo to seek opportunities in the new capital. He devoted his energies to preserving and restoring Urasenke’s cultural assets, which were on the verge of ruin after the Meiji Restoration. A liberal thinker, he published the magazine Konnichian Geppo [Konnichian Monthly Bulletin] to disseminate chado information, began the summer intensive seminar program to give students the opportunity to study at the headquarters, and systemized the curriculum to appeal to more people, especially women and students.

Ennosai passed away at the age of fifty-three, during the thirteenth annual summer seminar. His wife, Mokkyoan Soko, who had supported his efforts and worked with him to invigorate chado, passed away the following year, 1925.

14th Generation

Mugensai Sekiso Soshitsu (Tantansai) (1893-1964)

Ennosai’s first son, Masanosuke, was born in Tokyo in 1893. He graduated from Doshisha University in Kyoto and, in 1923, was formally recognized as heir apparent one year before his father suddenly passed away. In 1925, he took Buddhist vows under Abbot MARUYAMA Denne of Daitokuji temple, from whom he received the name Mugensai. Later, a member of the aristocratic Kujo family gave him the name Tantansai, by which he is usually known.

Tantansai presented tea to foreign dignitaries and members of the Imperial Family, including Empress Teimei and Crown Prince Akihito. He revived the custom of presenting kencha, “ritual tea offerings,” at well-known temples and shrines (the first was at the Grand Shrine at Ise), which sparked interest in chado throughout the country.

Tantansai’s konomimono, “favored objects,” are particularly numerous. Among his favored tea houses are the Toinseki, Kan’utei, Gyokushuan, Zuishinken, Bounseki, Seikoan, and Kojitsuken.

After leading chado followers through the desolate period for cultural activities during and after World War II, he devoted himself to restoring it to prosperity. Also, he was one of the first in the country to turn his attention to the dissemination of Japanese culture overseas. He sent his son to the United States of America and Europe to introduce chado. Later, he himself traveled to the U.S.A. and Europe on chado missions.

With the aim of unifying and encouraging the practitioners of the Urasenke tradition, Tantansai established the national membership association Chado Urasenke Tankokai, Inc. (now the Urasenke Tankokai Federation, an international Urasenke membership organization), in 1940. Nine years later, he founded the nonprofit organization Zaidan Hojin Konnichian (called Urasenke Foundation in English), thereby incorporating the Sen family’s estate and cultural assets.

For his efforts to further Japanese culture and chado, he was awarded the Medal of Honor with Blue Ribbon by the Emperor of Japan in 1957. In the same year, he also became the first leader in the chado world to be awarded the Medal of Honor with Purple Ribbon. In 1960, he received the decoration, Person of Cultural Merits.

Tantansai was active in many fields, including publishing. He expanded the Konnichian Geppo, which was renamed Chado Geppo [Monthly Bulletin of the Way of Tea], and edited and published the monumental work, Chado Koten Zenshu [Complete Collection of Chado Classics].

On September 7, 1964, Tantansai passed away during a trip to Hokkaido. He was seventy years old. He was presented posthumously with the Order of the Rising Sun, Third Class. His memorial is annually observed on July 5, jointly with that for Gengensai and Ennosai.

15th Generation

Hounsai Hanso (Sen Genshitsu) (1923-)

Mugensai’s first son, named Masaoki at birth, was born on April 19, 1923. He has had the names Soko, Soshitsu, and Genshitsu. His bynames include Hounsai, Genshu, Kyoshin, and Hanso. After serving in the air force division of the Japanese navy during WWII, he completed his temporarily interrupted university education at Doshisha University, Kyoto, graduating from the Faculty of Economics, He undertook Zen training and took the Buddhist tonsure under Goto Zuigan of Daitokuji temple, and was confirmed as Urasenke heir apparent in 1950. He succeeded as the fifteenth-generation head of Urasenke in 1964, upon his father’s death.

Hounsai has left a legacy of overseas Tankokai associations and has donated tea houses and tea rooms worldwide. He has proposed that chado is rooted in the combination of the way/principle (do), study/learning (gaku), and practice/practical skill (jitsu). He has personally been a dedicated student of the history and culture of tea, and holds a Ph.D. from Nankai University, China, awarded to him in 1991 for his successful defense of his thesis concerning the influence of the Cha Jing, by Lu Yu (8th c.), on the development of Japan’s chado culture, and a Litt.D. from Chung-Ang University, Korea, awarded to him in 2008.

He was the first in the chado world to be awarded the Order of Culture by the Emperor of Japan, and has been awarded many other decorations and merits from Japan and countries across the world. In 2002, he turned the headship of Urasenke over to his son, Zabosai, and took the name Genshitsu, but he continues to actively promote his goal, capsulized in the phrase, “Peacefulness through a bowl of tea,” by sharing chado internationally.

16th Generation

Zabosai Genmoku Soshitsu (1956-)

Zabosai was born on June 7, 1956, as Hounsai’s first son. His birth name was Masayuki. He has had the names Soshi and Soshitsu, and his bynames include Zabosai and Genmoku. He took the Buddhist tonsure under Nakamura Sojun of Daitokuji temple, and was confirmed as Urasenke heir apparent in 1982. In 2002, he succeeded as the sixteenth-generation head of Urasenke, and took the name Soshitsu. He has since put much energy into the education of younger tea practitioners and sought to clarify chado culture for all. He also fulfills his duties as head of Urasenke. In 2003, he held the 300th memorial observance for the fifth head of Urasenke, Fukyusai Joso; in 2007, the 350th memorial observance for the grandson of Sen Rikyu, Genpaku Sotan; and in 2020, the 250th memorial of the 8th head of Urasenke, Yugensai Itto at Daitokuji temple.

The Urasenke Legacy

Kabutomon “Helmet Gate” and the Roji “Dewy Path” walkway

The bark-roofed gate with bamboo guttering is thoroughly imbued with a wabi feeling. It was built during the Tempo era (1830-44) by Gengensai, the eleventh generation grand master. Seen from the garden side, the slightly curved sides and an arch-shaped cutout give the roof the appearance of a samurai helmet, hence the name Kabutomon, “helmet gate.”

A few steps inside the gate, a walkway of small paving stones, leading to the main entrance, angles off to the right through clipped hedges on both sides. As one proceeds down the walkway surrounded by dewy moss and luxuriant foliage, there is a sense of leaving the hustle and bustle of everyday life into a “mountain hermitage in the city (shichū no sankyo).”

Ōgenkan—Main Entrance Foyer

At the end of the walkway is the impressive main entrance to the tea room complex. Under a deep, bark-shingled eave, the paving stones give way to diamond-shaped tiles. A bamboo-floored landing extends across the width of the main section. A partial sleeve wall on the left side separates the main entranceway from a secondary entrance with its own stepping-up stone.

The right half of the main entranceway is in the formal shoin style with sliding wooden doors on either side of two shoji doors. The left half is in a less formal style with two shoji doors that slide past each other. The design elements convey unique expression and a sense of historic considerations of status and purpose.

Mushikiken “Shelter of Unchanging Color”

From the main entrance, a hallway leads back into the house to the Mushikiken, which functions as a waiting room (machiai). The original room is thought to have been built by Senso, but the present room is attributed to Fukensai, who had extensive changes made. The room’s name, “Shelter of Unchanging Color,” derives from the phrase “Pines throughtout time have unchanging color.” A wooden plaque with Chikuso’s calligraphy of this phrase hangs outside the room.

Two wide fusuma separate the main room of five tatami from an anteroom of three _daime_-size tatami. The wall at the right side of the guests’ area is papered and serves as the place to hang a scroll. A wooden-floored area the size of one tatami serves as a kind of toko alcove, where flowers are usually displayed. Formerly, this area served as a landing for a covered walkway which communicated to the Yanagi-no-ma anteroom of the Kan’untei. The sunken hearth (ro) is located in the right corner of the tatami where the host sits to prepare tea, above which is an attached shelf called Senso’s Kugibako-dana, “nail-box shelf.”

Waiting bench – Koshikake

The roji garden is entered from the Mushikiken. Against the garden wall is a sheltered waiting bench thought to have been designed by the fourth-generation grand master, Senso. It has a bark-shingled roof held down by a bamboo lattice and stones, a style of construction characteristic of the Kaga region where Senso frequently traveled. The stones in front of the bench indicate where the guests should sit. The Kinin-seki, “noble’s stone”, indicates the main guest’s seat.

Because Urasenke has many tearooms, the layout of the paths through the garden and the placement of the stepping stones, seen from the waiting bench, appear very complex. The roji extends to the tea rooms in two parts. From the waiting bench, a stretch of “scattered hailstones” pavement leads to the middle gate. The atmosphere here is created by the shading of the evergreen trees and the light and shadow created by sunlight shining through. Even the presence of those passing through seem to slip from view.

Because Urasenke has many tearooms, the layout of the paths through the garden and the placement of the stepping stones, seen from the waiting bench, appear very complex. The roji was skillfully laid out by Sotan with Konnichian and Yuin as the focal points. Beyond the stepping stones and a stretch of “scattered hailstones” pavement is the middle gate (chumon), with split-bamboo roof. Considered to embody Gengensai’s taste, it is a famous example of a light wabi-style gate.

The Yohobutsu-no-tsukubai

Along the way to the Yūin teahouse, there is a distinctive square tsukubai with Buddhist images carved in relief on the four sides, and is thus called the yohōbutsu no tsukubai. Nearby is a stone lantern which Kobori Enshū is said to have presented to Sōtan.

In front of the Kan’untei, there is Rikyū’s Kosode-no-tsukubai stone water-basin and Sōtan’s stone lantern. It is said that when Rikyu was about to be given a kosode garment by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, he asked for a garden stone instead, and was given the stone in front of Kan’untei. The name may also come from the resemblance to the Rikyu-favored kosode shape.

Even after constructing Konnichian, Sotan was involved in family matters. When the time came for his final retirement, he built a new retirement retreat, naming it “Yuin,” literally “again retiring.”

The dominant feature of the exterior of the teahouse is an imposing, rush-thatched, semi-gabled roof. The interior is of a conventional four-and-a-half-tatami layout, probably similar to Rikyu’s teahouse at his Jurakudai residence. A _daime_-size toko alcove is located on the north side, facing south. The toko post is Japanese cedar with knots on the bottom half. A utensil cabinet is built into the wall along the length of the tatami where the tea is made, which faces north. White paper wainscotting is pasted on the lower portion of the two walls bordering that tatami. The corner post has been plastered over to a height of one meter, and a hook for hanging a flower container is attached to the exposed section.

The “crawl-through doorway” (nijiriguchi) is located in the east corner of the south wall, and an exposed reed-lattice window is located diagonally above it. The only other window is located on the east side, in the wall behind the guests’ tatami. Both the south and east walls are covered with dark-blue paper wainscotting. The ceiling, of woven wooden slats with bamboo transverse pieces, is extremely low, only 1.75 meters from the floor. In the section of the ceiling which slants down to the south wall is a skylight, which can be pushed open through the thatched roof.

Yuin is considered an exemplary teahouse built according to the true principles of Tea.

Konnichian “Hut of This Day”

The tiny one-tatami-plus-daime room adjacent to the Kan’untei is the Konnichian, the tearoom whose name is synonymous with Urasenke.

The story of how the room got its name is well known. At the age of seventy-one, Sotan gave his son Koshin Sosa charge of Fushin’an and built a tearoom in the back garden as his retirement retreat. Upon its completion, Sotan invited his Zen master, the priest Seigan Soi, to a tea gathering. On the appointed day, Seigan failed to appear on time, and after waiting a while, Sotan went out. When Seigan finally arrived, he found Sotan’s message inviting him to come back the next day. Seigan scribbled his now-famous answer, “A negligent monk expects no tomorrow,” and went home.

Returning soon after, Sotan found the message and quickly grasped its meaning. Feeling shame for his insolence, he went to Daitokuji to apologize for his behavior that day. Later, he named the new tea room “Hut of This Day,” referring to the phrase Seigan had written.

The tea room represents the epitome of the thatched-hut style formulated by Rikyu. On the left side of the three-quarter size tatami (daime) where the tea is made is a built-in utensil cabinet, and on the far side is a wooden board inset. The fenestration of the outer wall features a small “poem card window” (shikishi mado) beneath a large window covered with two sliding shoji panels. A “crawl-through doorway” (nijiriguchi) is also located beneath this window at the south end of the one-tatami guests’ area. At the opposite end of the mat, a portion of the wall is set aside for hanging a scroll.

During a dawn tea gathering, the sunlight filtering through the trees strikes the shoji over the window in the east wall above the tatami where the host sits. The atmosphere created truly exemplifies Sotan’s wabi spirit.

Rikyu Onsodo, “Shrine of the Honorable Ancestor, Rikyu”

During the time of Gengensai, the Rikyu Onsodo Shrine was restored with funds donated by Lord KUJO Hisatada, and the wooden statue of Rikyu that had originally stood in the gate of Daitokuji temple was transferred here. A plaque written by Lord Kujo with the name Seijakuin, “Sanctuary of Tranquility,” hangs above the door.

Inside the shrine, the life-size statue of Rikyu stands behind a large round window at the back of an alcove. In front are a statue of Sotan in the seated position and a low altar table.

The main portion of the room comprises three tatami. A sunken hearth (ro) is cut in the board inset which separates the host’s and guests’ tatami. Senso’s suspended shelf, called the Hamaguri-dana, “clam-shaped shelf,” is at the far end of the host’s tatami. There is also a two-tatami anteroom which is used only on New Year’s Day and for traditional family rituals.

The Shaku-no-e-mado of Ryuseiken “Shelter of Restful Spirit”

The six-tatami Ryuseiken normally functions as the hall outside of the Kan’untei tea room. It is used as a tea room only on New Year’s Eve, to serve tea to guests who stop by to pay their respects. Afterwards, the charcoal remaining in the hearth is buried in the ash and left to smolder until morning. The embers are used to start the fire for the preparation of the Obukucha “Great Prosperity Tea,” which is offered before the statue of Rikyu. The water used for this tea is a mixture of water from the Ume-no-i “Plum Well” and water from the kettle which was left simmering on the hearth from the night before.

At the far end of the tatami where the tea is made, there is an exposed reed-lattice window. The handles of old bamboo ladles have been woven into the lattice. It is called the shaku-no-e-mado, the bamboo ladle window.

Kan’untei “Cold Cloud Arbor”

Because the wabi-style tea rooms Konnichian and Yuin were not appropriate for receiving members of the aristocracy, Sotan built a shoin-style room, Kan’untei. The room comprises eight tatami mats with a shoin window-shelf and an orthodox toko alcove. The painter KANO Tan’yu decorated the main room’s six fusuma panels with paintings of eight Chinese wizards. Next to the toko is a one-tatami space, called the Yanagi-no-ma, or “willow room.”

Although Sotan designed Kan’untei as a formal shoin, he imbued it with a wabi feeling through the unconventional use of architectural elements. For example, the room features a divided ceiling in three levels. The position of the sunken hearth (ro), in the right corner of the tatami where the tea is made, is also a feature conventionally used in rooms smaller than four-and-a-half tatami. Sotan also designed an arch-shaped transom inspired by a comb he received from Empress Tofukumon’in. Kan’untei is one of the most distinctive rooms in the compound because of its contrasting styles.

Totsutotsusai is an eight-tatami tea room built by Gengensai in 1839 in commemoration of the 250th memorial for Sen Rikyu. It went through a mild remodeling in honor of the Sen Sotan 200th memorial in 1856, when it received its name, the Totsutotsusai, which was one of Sotan’s Buddhist names. The toko (alcove) pillar is a log from a five-needled pine that the eighth grand master, Yugensai, had planted at Daitokuji. The baseboard and lintel of the toko are made of ivy wood that Gengensai received from the Hisamatsu family of Iyo Matsuyama (present-day Shikoku). The ceiling is crafted of old pine planks from Daitokuji. These were mounted in alternating directions forming a pattern called ichi kuzushi, variations on the Chinese character for “one.” The auxiliary alcove features a large, exposed reed-lattice window. Totsutotsusai is used for the first tea gathering of the year (Hatsugama) and other Urasenke observances. The grand master also serves his personal guests here, and many royal visitors, world leaders, and other distinguished personages have been served tea in this room.

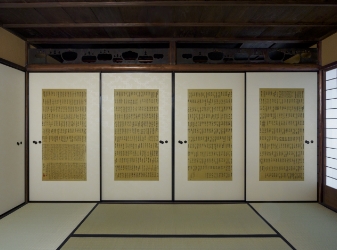

The anteroom of Totsutotsusai is called Tsugi-no-ma or Dairo-no-ma. It is a six-tatami room having a large sunken hearth (dairo) that is used only during the month of February. Four fusuma, called the Hogo-busuma, separate the Dairo-no-ma from the Totsutotsusai. Gengensai wrote a list of the major styles of tea making (temae) and the one hundred didactic poems attributed to Rikyu on the panels.

The water of the Ume-no-i, “Plum Well,” has long been considered ideal for making tea. On New Year’s morning, using water drawn from this well, the grand master prepares Obukucha, “Great Prosperity Tea,” which is offered before the statue of Rikyu in the Onsodo.

Next to the Ume-no-i is a tall water-basin made of a unique stone which reveals chrysanthemum-shaped patterns on its cut interior. The stone was a gift from the Owari Matsudaira family.

Hosensai “Room of the Discarded Weir”

The Hosensai is a twelve-tatami room built by Gengensai. The name of the room comes from one of the names used by Rikyu. The room has a toko alcove wider than the length of a standard tatami. There is an auxiliary alcove having a built-in floor-level cabinet with sliding doors and a suspended shelf. In front of the toko alcove are two tatami with patterned edging which demarcate a special seating area reserved for members of the nobility.

The room is bordered on two sides by a veranda which opens onto the inner garden. The focus of the garden, which was laid out by Gengensai and renovated by Tantansai, is an aged red pine called the “Reclining Dragon.”

Yushin “Shelter of Newness Afresh”

To commemorate Tantansai’s sixtieth birthday, his wife, Kayoko, designed this tea room. The room is significant because it was the first built specifically to serve tea using benches and tables. The tile-floored main area is set with a specially designed table for preparing tea, and tables and benches for the guests. In the corner of the room is an L-shaped alcove with a lacquered shelf at the same level as the tabletops. The ceiling is made of old beams, smoked bamboo, and woven reeds, which convey a rustic feeling. Adjacent to the tile-floored area is a raised six-tatami room.

Tairyuken “Shelter Facing the Stream”

Ennosai built the fourteen-tatami room Tairyuken in 1923, the year in which his grandson, later the fifteenth-generation grand master, was born. The size of the room can be doubled by removing the shoji panels to incorporate the space of the surrounding corridors. The toko (alcove) pillar was made from a pine tree that grew outside the Yuin tea room. The cloth covering the doors of the cabinet in the auxiliary alcove was a gift from the aristocratic Kujo family. The altar curtain in the Rikyu Onsodo is also of this cloth. On the opposite end of the room there are four fusuma panels decorated with a scene of a stream flowing amid rocks and pines, by Maruyama Denne Roshi of Daitokuji temple.