River Wey & Navigations : The River Wey (original) (raw)

A Town with an Ancient Association

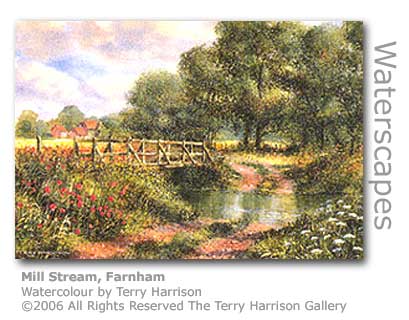

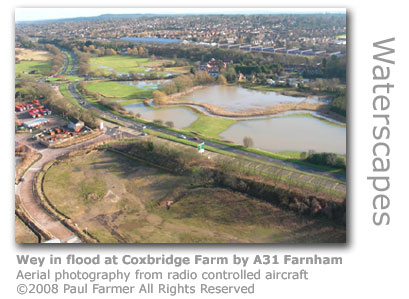

Having skirted the edge of the Alice Holt Forest the Wey, now in the county of Surrey, continues on an easterly heading until it serves to divide the ancient town of Farnham with its sprawl of suburbs both to the north and south.

‘. . . being surrounded by dreary heaths covered in sand and fern.’ Richard Gough and William Camden. Camden's Britannia 1789

It is here in Farnham that the river at last benefits from a little more recognition with the local town planners having retained rights of access for the benefit of Farnhamians. There is ample archaeological evidence that the river has attracted human settlement here for many thousands of years, the town having grown around a hub of roads converging on a natural ford. It is also at Farnham that the river takes a sharp right turn and heads almost due south to pass the site of the highly influential 12th century Waverley Abbey from which the local governmental body takes its name. The Wey finally meets its southern twin at the picturesque village of Tilford.

click on image to go to artist's website

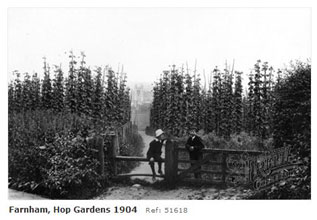

Farnham has always been an industrious town and was renowned for the unbeatable quality of its hops which were in considerable demand from the brewing industry. It was not surprising therefore that all the way along the valley brewing was very conspicuous, and especially so in Farnham. Huge acreage of prime farmland was dedicated to Farnham Hops from the 17th to 19th centuries, and were grown primarily in the area from the foot of the Hog’s Back chalk ridge and Wrecclesham, and also at Bentley. Having been originally introduced from Suffolk, in the mid 17th century the hopping acreage increased from 300 acres in the late 17th century to a peak of 5,930 acres in 1885. Hops are still grown today in a small way in Puttenham lying in the shadow of the Hog’s Back.

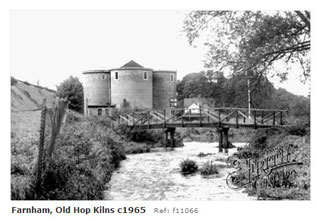

Hop Kilns, Farnham 1965 Reproduced courtesy of The Francis Frith Collection

Hop kilns, where the hops were dried out before being delivered to the brewers, no longer exist as working kilns in the area, although now many can be seen converted into private dwellings at Frensham, Tongham and Puttenham. The process of malting, which is the preparation of barley for beer, was mainly undertaken on a small scale along the valley and there are remains of maltings in Tongham, Badshot Lea and Wrecclesham. Numerous malting floors and kilns, which once serviced all of the taverns that brewed their own beer, are in evidence in old buildings centred on West Street and Castle Street in Farnham.

Hop Gardens, Farnham 1904 Reproduced courtesy of The Francis Frith Collection

Hop Gardens, Farnham 1904 Reproduced courtesy of The Francis Frith Collection

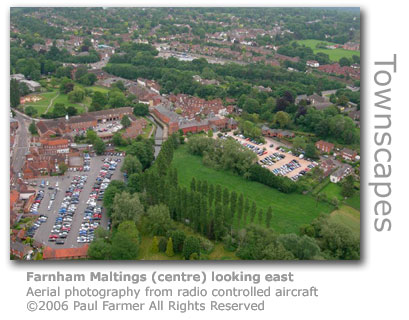

The only significant surviving evidence of the importance of the industry are the 19th century buildings of Farnham Maltings (GR: SU838464) which stand quite austere alongside the River Wey near the centre of the town. The complex has served as both a brewery and maltings, and earlier as a tannery. The brewery of one John Barrett was in full production here in 1845 until Courage took the building over in 1920 and converted it into maltings. By 1956 new malt production methods dictated that production on this site was no longer economic and the buildings were closed lying derelict until 1968. An appeal raised £28,000 by public subscription to secure the maltings for the town and it was converted into an arts and community centre which succeeded in keeping the building open for public use.

click on image to go to photographer's website

Today the only brewery in operation locally is the Hogs Back Brewery on the Manor Farm Industrial Estate in nearby Tongham. Famed for its flagship ale TEA (Traditional English Ale) the brewery launched in 1992 with their first brew of 10 barrels (3,000 pints) which was sold to local pubs. The original brewhouse is housed in one of the 18th century barns the brewery occupies, and with their output now (2008) exceeding 140 barrels (40,000 pints) a week the company has absorbed all of the old farm buildings available to them. The story goes that the brewery was launched by a chance conversation in 1989 with the editor of The Grist, the brewery trade publication, who so enthused Tony Stanton-Precious that he and co-founder Martin Zillwood-Hunt went out and bought some Burco Boilers (typically used in village halls and cricket clubs for heating water for a brew) which stood in for a mash tun and he produced their first trial brew, Ash House Bitter. Today's brews include aptly named Santa's Wobble, Still Wobbling, Wobble in a Bottle, and Rip Snorter, amongst many others. The design of the label on Burma Star Ale depicts Martin's father who fought in Burma during WWII. The Hog's Back Brewery has won great acclaim since it was founded and has won numerous awards including Champion Beer of Britain in the Best Bitter class of the CAMRA Great British Beer Festival (2000).

On land right behind the brewery in Tongham an application has been made to drill for oil. A public meeting held (May 2009) at the Hog's Back Hotel by local protesters revealed that a 124ft (38m) high rig would be erected within a quarter of a mile of homes and would be operated 24 hours by Magellan Petroleum. Guildford Borough Council have logged almost 300 letter of objection. There is local speculation that the company is also considering another site at Binton Farm in Seale.

The river runs in Farnham alongside a pleasant park and under a decorative modern bridge before bubbling beneath what was originally the town’s only bridge crossing the Wey, and hence is called Farnham Bridge (GR: SU841466). This is the first of a whole series of medieval bridges that were built by the Cistercian monks from Waverley Abbey to bridge the river from here to Guildford in the 13th century. Consecutive remedial works have much altered the bridges over the centuries, but they are considered to be of a unique design with unusual rounded cutwaters. Others in the series include Waverley Mill Bridge, Tilford Mill Bridge and Eashing Bridge.

click on image to go to photographer's website

Watermills

Further downstream the only other remaining watermills on this stretch of the River Wey have been preserved in as much as they have been converted for other uses.

See you our little mill that clacks So busy by the brook? She has ground her corn and paid her tax ever since Domesday Book. Puck of Pook's Hill Rudyard Kipling 1906

The Domesday Book of 1086 identified six mills in Farnham each valued at 46s 4d and at the time provided a combined income of £139 for the Bishops of Winchester who owned the freehold.

A mill has stood on the site of Willey Mill (GR: SU817451) to the west of the town since Norman times and was owned by the all-powerful Bishop of Winchester from 1207. At least three mills have operated on the site. Records show that a mill was rebuilt here in 1370, replacing one that had fallen into disuse. It is likely that the mill in the 1380s fell silent once again in the aftermath of the Black Death as this 1389 entry in the bishop's rent rolls relating to a fine levied for default of rent testifies:

‘Whelye mill, 3 crofts and moor of free land adjoining, formerly belonging to John Wolfriche, in default of tenants, by reason of pestilence’.

Few later records exist save to show that Willey Mill was marked clearly on Ogilby's map of 1675 and again in the map drawn by John Senex in 1729. The existing building looks to date back to the middle of the 18th century and is built of brick and local Crondall stone. In the 1920s the domestic facilities at the adjoining mill house were barely changed from previous centuries. The toilet was at the bottom of the garden with a sluice down to the river, and water was drawn from a hand pump by the house and stored in a barrel which often froze in the winter. The house in the absence of electricity was lit by candles and paraffin lamps.

The mill ceased to operate commercially in 1953 having been able to provide at its peak the considerable output of one ton of wheat ground for a single pair of stones in an eight hour working day. Before the buildings became completely redundant four years later, a 19th century cast-iron waterwheel provided power for a chaff cutter, an oat roller and a crushing machine used in the manufacture of cattle cake. the property was sold as a smallholding, poultry farm and private residence in 1957. The waterwheel was removed in the 1960s. Much of the old wing of the property was destroyed by faire during restoration work in 1975.

The buildings have since been renovated for a variety of uses including an art gallery, antiques centre and offices, and are currently occupied by a company providing a training and conference centre. In a 1996 sale of the property it was described by the agent as ‘a perfect Georgian country house, straight out of Jane Austen’ and had nine acres of meadowland, two trout tanks, a smoking-room, gallery and showroom.

The name 'Willey', which has undergone various spelling variations over the centuries, has several likely explanations'. In the 14th century the Wuley family owned the tenancy for the mill, and one school of thought suggests that the mill became know as 'Wuley Mill' later verbally illiterated to 'Willey'. Others opinion that the family took their name from the mill and that the land was named after the the river Wiley in Wiltshire, although why the connection arose is not clearly documented.

Weydon Mill (GR: SU836462) at the end of Red Lion Road was one of six mills documented in the Domesday Book for the parish of Farnham, and later in the Bishop of Winchester’s 1258 Pipe Rolls. By 1653 the mill had developed to such an extent that there were three watermills operating on the site under a single miller. The final mill building, that had been built on the site in the 18th century, became the focus of a passionate battle between the local population and the owner after the mill had ceased operating in 1909. The occupier, a local brewer, did not share their concerns in wanting to preserve the building and demolished it in 1919. The miller’s house survived until 1957 when it too fell to the same fate.

Farnham Hatch Mill (GR: SU846470) now rests by the side of the busy Farnham by-pass on a site with a long history of milling. The monks from the nearby Waverley Abbey had a fulling mill here in 1231, and later records show there was a corn mill here leased from the Bishop of Winchester in 1691. By 1889 milling had ceased with the river diverted away and the building used as a dairy and firewood factory, and from the turn of the century until 1962 it served as a laundry. Thereafter the building has showed incredible flexibility having become a civil defence centre in the 1960s; a depot for a motor oil firm; as an arts centre and rehearsal studios for the local and now defunct Redgrave Theatre; and in 2001 was adapted for use as a care home. The original mill is an attractive three-storey building of red brick with a lunette door at one end. The adjoining mill house dates from the 18th century.

Hatch Mill at Farnham 1904 Reproduced courtesy of The Francis Frith Collection

High Mill (GR: SU857472) on the eastern edge of the town remained a working mill until 1950 and still retains some of the pit machinery and an undershot waterwheel. The building straddles the River Wey with two by-pass channels having been built as a water control feature to prevent flooding on this low-lying position. Records for mills on this site go back to one in 1288 that records the woes of a corn miller who was evicted and fined for what was then the considerable sum of 20 shillings in the process. For centuries the mill was owned by the Bishop of Winchester. Fulling was undertaken here in 1692, and the mill was in decline by 1900 when the miller had fallen back on milling provender food for horses.

The mill finally closed in 1950 having been used for a period merely as a saw bench. The mill is quite unique in the county for its unusual primary drive machinery that once powered two sets of stones, although one set was later removed. There had been a second waterwheel at the mill at one stage powering fulling machinery. Although there is no direct access to the mill house which has been converted to a private dwelling, there is a public footpath that passes across right to the front of the building, no doubt causing considerable chagrin for the current owners.

Although not on the River Wey, the Bourne Mill (GR: SU852474) straddles a tributary and is a fine example of a 17th century mill building, being one of the oldest remaining in Surrey and is said to be the longest continuous site of business in Farnham. The last of several mills occupying the site by a large millpond, this mill ceased in 1906 and having served for a time as a drinking club in the 1960s now has been preserved as a fascinating antiques and crafts centre with full access to the public, and is well worth a visit. The front of this five-storey mill has been modified by the installation of modern windows and four-stepped buttresses to support the façade.

Another tributary mill located adjacent to Moor Park was Rock Mill (GR: SU857472). All that remains now of this once highly productive mill, originally erected in 1770, are its considerable brick foundations having been demolished some time after its closure in 1877. Owned by the influential milling family of Simmonds, the mill at its peak had five pairs of stones driven by a 10 horsepower Corliss engine.

River Blackwater

Once a significantly larger river than now remains, the River Blackwater rises at Rowhill Nature Reserve (GR: SU848499) between Weybourne (Farnham) and Aldershot and serves as a 17 mile (27 km) tributary to the River Loddon with its confluence at Swallowfield near Eversley in Hampshire

Rowhill was once part of an extensive heathland but now lies isolated by urban development, separated from the remaining heath that today serves as a training ground for the army.

River Blackwater near Eversley

Image in public domain

The Blackwater is significant to the Wey in that close to its original source a stretch of the river's headwater was captured by the Wey resulting in the original early course of the river being significantly altered. This ancient river cut its way through the Tertiary deposits and eroded the sands and gravels to form a wide flood plain. Consequently the modern Blackwater is a small river sitting in a wide flood plain, beneath which lie valuable mineral deposits.

The following is an extract from a text book for engineers published in the 1950s.

River Capture. It sometimes happens that a river which is cutting back vigorously in an easily eroded formation may approach the course of a neighbouring stream, and meet and divert the headwaters of the latter into its own channel. This process is known as river capture; The stream which has lost its headwaters is said to be beheaded, and dwindles in size until it has become obviously too small for the valley in which it flows, and is called a 'misfit'. An example is provided by the River Blackwater near Farnham, Surrey, a tributary of the Thames. The course of this now small stream once extended much further to the south-west, whence it transported distinctive gravels containing chert, to deposit them north of the gap in the Chalk ridge at Farnham. The source rocks of the gravels prove the former extent of the river. An eastward flowing stream, the Wey, cutting back rapidly from Godalming in soft strata, tapped the upper reaches of the Blackwater and diverted the flow into its own channel. The point of capture is marked by a right-angle bend which the river makes just east of Farnham. Geology for Engineers by F.G.H. Blyth, published by Arnold, third edition, 1952.

Acknowledgement:

Many thanks to Peter Weedon for sourcing and providing the above excerpt.

Construction of the A331 Blackwater Valley Relief Road at a cost of £170m required the construction of the Ash Aquaduct (GR: SU887514) to carry the Basingstoke Canal over the road and the Blackwater River, which previously had been routed beneath the canal embankment via a culvert originally excavated in the 18th century when the canal was built. In constructing the aquaduct an important colony of bats that had made home in the culvert had to be rehoused in a purpose-built bat roost on a nearby island. The aquaduct took nine months to construct and was officially opened in July 1995.

Excavations at Tongham have revealed the presence of Iron Age farmsteads in the Blackwater Valley floor.

The travel writer Daniel Defoe painted a bleak picture of the heathlands in the local area in the 18th century:

Much of it is sandy desert where winds raise the sands…The ground is otherwise so poor and barren, that the product of it feeds no creatures but some very poor sheep, and but few of these, nor are there any villages worth remembering and but few houses or people for many miles far & wide. This desert lies extended so much that some say there is not less than a hundred thousand acres or this barren land… reaching out every way in the three counties of Surrey, Hampshire & Berkshire. Daniel Defoe 1724

Long prized as a source of gravel the Blackwater Valley has had a number of significant quarries sited there, many of which have been converted into lakes once extraction ceased. A string of these lakes run along the length of the southernmost stretch of the river between Farnham and Frimley, with a large example close to Weybourne (GR: SU863491).

Rowhill Nature Reserve

Rowhill Nature Reserve (GR: SU848499) in Rowhill Copse comprises of 55 acres of mixed deciduous woodland and working hazel and sweet chestnut coppice, and is the source of the River Blackwater.

Interspersed with the woodland is a diverse range of habitats including meadow, heathland, sphagnum bog, pine woodland and streams and ponds. The reserve provides a wonderful display of spring flowers including bluebells, violets and wood anemones.

The Blackwater Valley Path that runs alongside the full length of the River Blackwater originates in the reserve.

The Rowhill Nature Reserve Society was founded in 1968 and its volunteers manage the reserve on behalf of Rushmoor Borough Council. There is a field centre in the reserve which is opened on Sundays and Bank Holidays, and also provides education facilities for local schools.

Moor Park Nature Reserve

It is at Farnham that The Surrey Wildlife Trust has preserved an important part of the River Wey’s natural heritage by setting up a Nature Reserve at Moor Park (GR: SU867459) and which has been designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSCI).

This 19 acre reserve has saved the last remaining deep water alder swamp left in Surrey, and in the alder woodland, riverside clearings and reed beds, a diversity of wildlife can be encountered. The alder carr, or wet woodland, is nationally a rare habitat and at Moor Park has developed naturally over the last 200 years. It is now almost self-sustaining thanks to the work of the Wildlife Trust. The extent of bird life is considerable with Redpolls, Siskins and mixed flocks of Tits visiting over winter to feed on the Alder cones. Waterfowl are regular visitors especially in difficult weather with Mallard, Teal, Tufted Ducks and Swans regularly using the alder carr for shelter. The reedbeds contain a variety of plants which support nests of Reed and Sedge Warblers, with Water Rail often in residence. Kingfishers and Heron also frequent this stretch of the river in search of the abundant fish found in its waters. Other species to look out for are Grey Wagtails, Pochard and Sparrowhawks. The rich resource provided by natural flooding here provides a perfect habitat for butterfly caterpillars including the Peacock butterfly, although you will also have a chance of glimpsing other species including Orange Tip, Holly Blue, Brimstone, Comma, Green-veined White, Small White and Meadow Brown.. In addition to the Alder the reserve has impressive specimen of Crack Willow, Goat Willow, Pendunulate Oak and Beech. For plant lovers the common and rarer species thriving in the habit provided here include Branched Bur-reed, Great Pond-sedge, Marsh Violets, Opposite-leaved Golden-saxifrage, Water-plantain, Hemlock Water-dropwort and Moschatel. Three species of bat have made the reserve their home, and Roe Deer can often be seen here.

Moor Park Estate

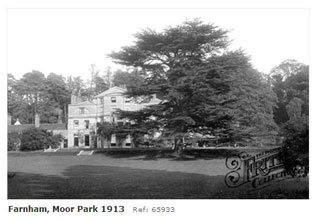

Moor Park itself, which runs along the eastern bank of the river as it heads southwards towards Tilford, was an estate of considerable influence in its time. The house (GR: SU862466) was built in 1630 and one owner, the influential statesman and diplomat Sir William Temple (1628 –1699) lived here for 15 years until his death. Originally known as Compton Hall, Temple renamed it as Moor Park after the estate in Hertfordshire where he and his wife Dorothy Osborne had spent their honeymoon. He created a fascinating garden in the Dutch style complete with a canal.

Such gardens became the height of fashion, especially as the new monarchs at the time William & Mary were gardening enthusiasts and actively promoted the Dutch style. Temple, who had helped negotiate the marriage of William of Orange, often hosted the king at Moor Park and on one visit the king demonstrated to Temple’s young secretary the Dutch method of cutting asparagus. The secretary who worked for Sir William during the last ten years of his life was none other than Jonathan Swift (1667 – 1745), later famous for his novel Gulliver’s Travels. Swift, then in his early twenties, shared Temple’s enthusiasm for gardening and the Wey Valley which he was to influence him throughout his life. He wrote Tale of a Tub’ and the ‘Battle of the Books’ whilst at Moor Park. Following Sir William’s death the house was left to his granddaughter who further extended the area of the garden. Swift had also met Esther Johnson, the eight year old daughter of one of the maids at the house, who he immortalised in his poems and Journal. The Temple’s family coat of arms can be seen cast in iron over the main entrance to Moor Park house.

Moor Park 1913 Reproduced courtesy of The Francis Frith Collection

Moor Park 1913 Reproduced courtesy of The Francis Frith Collection

“On the outsides of the grass-walks were borders of beautiful flowers. I have stood for hours to look at this canal, for the good-natured manners of those days had led the proprietor to make an opening in the outer wall in order that his neighbours might enjoy the sight as well as himself. I have stood for hours, when a little boy, looking at this object; I have travelled far since, and have seen a great deal; but I have never seen anything of the gardening kind so beautiful in the whole course of my life.” William Cobbett The English Gardener, 1833

Charles Darwin was a guest at Moor Park in 1859 where hydropathic treatment was provided to him, and he gave an insight into his activities there in a letter he had penned to his son at Cambridge.

“Moor Park has not done me quite so much good as heretofore, but I hope it yet may: I cannot walk far & get to a kind of Barometer which I have here, namely Crooksbury Hill, when I can get to top of that all is splendid but half-way beats me as yet. Nor can I get up to my old standard in Billiards. There is a young Irishman here, who plays capitally & gives me lessons: he always is hitting his own ball on one side, but Dr. Lane says that if I take to that I shall never learn, so that it is hard work to settle between my masters.” Charles Darwin 1859

There remains little today of Sir William Temple’s original 17th century gardens. The once very grand ornamental canal now remains merely as a circular pool with small arms to the north and south. However a ‘jet d’eau’ fountain from the late 17th century was still working well into the 20th century. The house, a grade II listed building, has been converted to offices and workshops and neither the house nor the grounds are open to the public, although viewing may be possible by special appointment. Under the lawns an ice house is preserved. Measuring 15 ft long, 6 ft wide and 8ft high (4.6m x 1.8 m x 2.5m) the facility indicates just how important Moor Park must have been on the social calendar. Close analysis has found traces of fat coating the bricks suggesting that in later years the structure may have been converted into a smokehouse for meat products. There is a smaller ice house in an earth bank near the main gate.

The Lodge by the gates at Moor Park House bear the arms of Sir William Rose, and it was Rose who in 1897 tried to put an end to free access to the bridle path that runs by the house. The resultant Battle of Moor Park in which an army of local militants stormed the gates prising away padlocks and chains in order to re-establish their right of way - which remains today.

Mother Ludlam's Cave

Alongside Moor Park buried deep into the hillside are two caves, in the larger of which (GR: SU872457) local legend has it that a kindly woman, Mother Ludlam, lived. Named after the area which was called ‘Luddwelle’, Mother Ludlam, who was mentioned in the ‘Antiquities of England and Wales’ 1775, was well known for helping poor people by lending them cooking utensils and even furniture. This kindness ceased when a large copper cauldron she had loaned out was never returned, the cauldron itself ending up at Waverley Abbey and eventually the church at Frensham. The original account became increasingly embellished with ever grander tales of a witch in the caves casting spells of retribution.

In the 18th century the cave was turned into a grotto which were popular at that time, and a steam running down the centre was made a feature with paving, seating and iron drinking vessels being provided for visitors to sample the spring waters. The cave is home to three species of bat: Natterer’s Bat (Myotis nattereri), Daubenton’s Bat (Myotis daubentonii) and Long-eared Bat (Plecotus auritus). At the turn of the 20th century Greater Horseshoe Bats were recorded here too, although by mid century their numbers had plummeted by 99%. Conservation efforts today are gradually seeing a return of the Greater Horseshoe population.

Daubenton's Bat (Myotis daubentonii)

Image in public domain

The cave has been neglected for some time, as even this account by William Cobbett shows. Little has changed since apart from an information board posted by the Waverley Borough Council as part of their Moor Park Heritage Trail.

'Alas it is no longer the enchanting place that I knew it. The semi-circular palings are gone; the basins to catch the never-ceasing little streams are gone, the iron cups, fastened by chains for people to drink out of, are gone; the pavement all broken to pieces; the seats for people to sit on, on both sides of the cave, torn up and gone; the stream that ran down through a clean paved channel, now making a dirty gutter; and the ground opposite, which was a grove chiefly of laurels, intersected by closely mown grass walks, now become a poor ragged-looking alder coppice.' William Cobbett 1825

12th Century Cisterian Order

Waverley Abbey

After Moor Park, as the Wey heads southwards towards the abbey, the river passes beneath Waverley Mill Bridge (GR: SU870455) another of a series of medieval bridges spanning the river from Farnham to Guildford that were originally built by the abbey’s Cistercian monks. Waverley Mill (GR: SU871455) was also originally associated with the influential and powerful monastery further downstream. The mill was still operating as late as 1895, but following a severe fire the building was demolished in 1900. The small brick and stone building that survives was built to generate electricity from a water turbine. The pretty miller’s house has been preserved and renamed as Mill Cottage, and by the mill site there are the remains of an old sluice gate constructed from ancient elm boarding that was once operated by chains and levers.

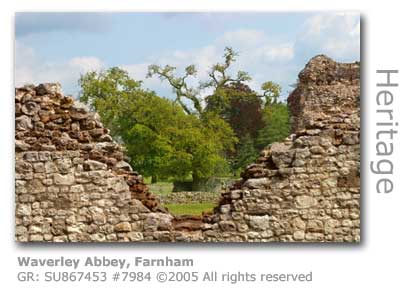

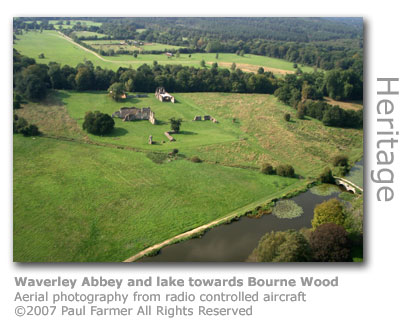

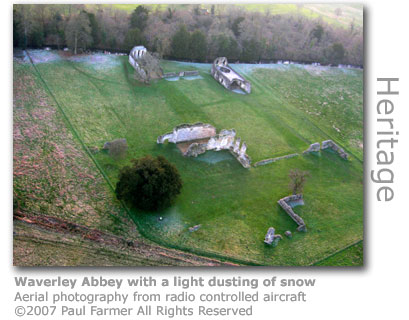

Three miles south of Farnham the first Cistercian monks to establish an order in Britain arrived at this picturesque spot on the banks of the River Wey and decided to build their abbey here. The construction of Waverley Abbey (GR: SU867453) was started in 1128, having been gifted the land by William Giffard who as the Bishop of Winchester controlled much of the region. The swamp and common lands here were then part of what was known as 'The Greensands', a swathe of land incorporating what today is the borough of Waverley and stretching across to Winchester in Hampshire.

The small colony that had emigrated from France consisted of only an abbot and 12 monks. Their creed was of reformation and involved a simple and austere form of monasticism based on the 6th century teachings of St Benedict based around devotion to prayer, study and labour. Their name derived from the abbey of Cireaux in Burgundy and they quickly became known as ‘white monks’ as they wore habits of undyed wool. By 1187 the community supported 70 monks and 120 laybrothers.

Life in the early years, as Waverley Abbey was developed, were full of hardship. For example in 1208, 80 years after the abbey had been established on the bank of the Wey, the original primitive shelters were only beginning to be rebuilt into a more permanent and decorative structure. The new development work by this time had been in progress for several years, but building was slow and had been hampered by the effects of famine following several bad harvests. A sequence of wet years had also led to the Wey regularly flooding the open riverbank site. Once completed the abbey was to cover eight acres of drained marshland, a considerable undertaking. William Broadwater, the priest who was masterminding the project, had persevered against all odds, but he hadn’t predicted the biggest obstacle that was about to fall in his way. The King of England.

click on image to go to photographer's website

King John had upset the Pope that year, and the Pope had retaliated by issuing an edict forbidding access to church services and ecclesiastical privileges. This sort of action in its day was extreme, and would normally have brought even a king to heel. Everyone regardless of status was God fearing, and genuinely fearful of not being able to have their souls saved from purgatory. But not King John. He seized church property in retaliation instead, and Broadwater suffered the Abbey’s assets confiscated alongside all the churches in the area..

Even worse for Waverley Abbey was that the king chose to spend Easter week as a self-invited guest there, with the stated intention of ignoring the Papal edict and to attend services at the abbey. The brothers were expected by the king to ignore the ban too, and naturally also provide the lavish hospitality that a regal party would expect. Having no choice, Broadwater rolled out the red carpet and set about entertaining King John and his large entourage.

By all accounts the brothers at the abbey did such a good job that King John, who was sorely impressed with their hospitality and their humility, directed that the seizure of their assets should cease forthwith, and ordered that any possessions so far confiscated be returned. Many of these possessions would have been property from which rents were due, vital to fund the building programme. And so the day was saved and Waverley Abbey was able to continue to become the hugely successful and influential body history records it as being today.

click on image to go to photographer's website

By the time the abbey was fully dedicated in 1278 the buildings centred on an imposing church that was 300 feet (91 metres) long and 150 feet (45 metres) wide at its transepts. Such were the capabilities of the community that over 7,000 guests were reportedly invited to the dedication including abbots, knights and lords and ladies.

It is thought that great entrance gates complete with a gatekeeper's tower once stood where today the B3001 takes a tricky double bend to cross the river by the weir.

This success of the Cistercian order’s first community inspired others to start up, and by 1150 five other communities had been established. These included Fountain, Reivaulx and Tintern. Part of this success is attributed to the fact that the order provided for an opportunity for uneducated Laybrothers to be recruited from the local peasantry, and it was these Laybrothers who, grateful for the security of monastic life, undertook all of the considerable manual labour the day-to-day running of the abbey required.

The Cistercians were at the forefront of agricultural development in the 12th century, and by 1300 Waverley had 14 farms (‘granges’) which included valuable stocks of sheep enabling the monks to undertake a lucrative trade in wool with merchants as far away as Flanders and Florence. The wool was shorn from sheep bred from the original flock brought over from France when the abbey was first established. Wool produced in England was considered to be the best quality in Europe at the time. Although much of the abbey’s income was earned from farming, much benefit was gleaned from the various properties gifted to them by the Bishop of Winchester, and rents were regularly received from properties owned in London and Great Yarmouth, as well as tolls and fees from the market at Wanborough.

click on image to go to photographer's website

The abbey fell to the wholesale destruction wreaked by Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries from 1536, and despite the abbot’s protestations to the outside world the buildings were systematically stripped of their finery, and eventually even the fabric of the buildings were dismantled to be used as building materials elsewhere. It is thought that many of the great houses between the 16th and 18th centuries in Surrey took advantage of building materials from the ruined abbey including Loseley House near Guildford.

Today little remains of the splendour of the place, but the ruins are nevertheless still impressive and give a good idea as to exactly what this industrious community of brothers had achieved. Now in the care of English Heritage the site has been well preserved and is open to visitors for no charge all year round. Local folklore has it that the ghost of a monk who was hung, drawn and quartered during the Reformation walks the nave of the chapel ruins on moonlit nights.

The publishing of the abbey’s own 13th century historical account, Annales Waverliensis, in the late 18th century revitalised an interest in what by then was merely a largely forgotten ruin on a meander of the River Wey. This account also, according to some sources, provided inspiration for Sir Walter Scott’s Waverley novels. Scott (1771 – 1832) was largely saved from bankruptcy when Waverley, his first novel, was published in 1814.

click on image to go to photographer's website

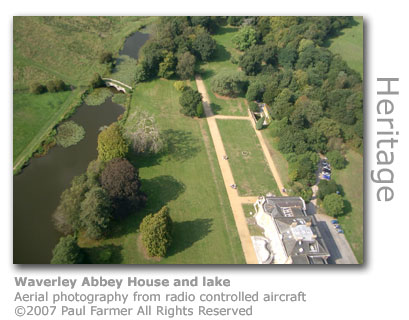

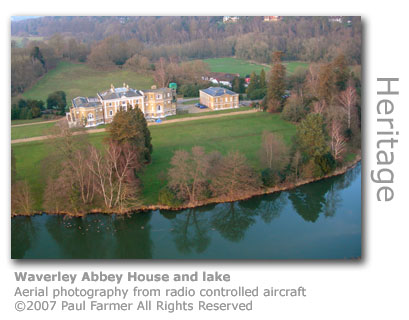

Waverley Abbey is in a beautiful location with the river behind and meadows all around. Facing the ruins is Waverley Abbey House adorned with landscaped gardens and an ornamental lake and bridge. This impressive Georgian house is attributed to the architect Colin Campbell and is currently occupied by Crusade for World Revival, a religious organization established by the Welsh preacher Selwyn Hughes in 1965. The house and gardens are not open to the public, although the public footpath leading to the abbey skirts the edge of the lake and affords perfect views of the house.

Under the auspices of English Heritage the ruins have served as a film & TV location which recently included Hot Fuzz (2007) starring Simon Pegg and Nick Frost and Elizabeth: The Golden Years (2006). Part of an episode of TV murder mystery series Miss Marple was shot here as were photographs for the Ted Baker Fashion Look Book.

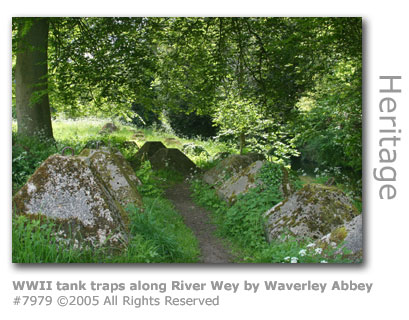

There still remains evidence on the site and in the surrounding area of the 'GHQ Line', the line of defence built during the Second World War that circled London. A large brick gun emplacement dominates the entrance to the ruins and original tank traps are still in position behind the Abbey buildings where they flank the river.

Black Lake

A few hundred yards to the west of the river across the Tilford Road from Alice Holt Forest is Black Lake (GR: SU863446) set in a heavily forested area.

The author of Peter Pan, JM Barrie (1860 - 1937) lived in Black Lake Cottage here and fondly called the woods around his cottage 'the haunted groves of Waverley'. The lake inspired Barrie to write The Boy Castaways (1901) which is said to have provided Barrie with the next link to creating Peter Pan. Barrie's original title for the novel was The Boy Castaways of Black Lake.

JM Barrie

Image in public domain

Writer Andrew Birkin visited Black Lake to undertake research for the BBC's Lost Boys, where it was hoped that they would be able to film in the location that Barrie had set the story.

"I decided to go and take a look to see if it still existed. Which indeed it does, on the left-hand side of the road from Farnham to Tilford. Black Lake Cottage is on the other side of the road, and was in those days owned by a somewhat taciturn businessman who tried to sell me “Barrie’s armchair”, stored in his tennis pavilion – Mary Ansell’s gardens having been replaced by a large tennis court. But the house itself looked much the same as in the photographs in her books about Black Lake, and certainly the owner proved agreeable to letting the BBC shoot there ... for a sizeable consideration.

"I had better luck across the road, where the owners of the Black Lake itself were delighted to see a copy of the surviving Boy Castaways. Nor did gold light up in their eyes at the prospect of a BBC location. There was only one problem: the lake had virtually disappeared. But since 1976 was a freak summer and we wouldn’t be shooting till the following year at the earliest, it seemed reasonable to hope that by then the lake would be once again be restored to a South Seas lagoon. The owners had inherited a story to the effect that the punt used by George and Jack to explore the “island” (there isn’t one) lay somewhere at the bottom. I waded across the muddy sink, but all I found was a cricket bat ...

"At last I was left on my own to explore at will. The forest looked very similar to the 1901 photographs, prosaically explained by the fact that the original pine trees had been planted in 1860, felled during the Great War, replanted and felled again in 1940 - thus the new trees planted during WW2 were roughly the same age and size as the ones in The Boy Castaways. But it was the spirit of the place that I remember best – the “haunted groves of Waverley” as Barrie called them. I had the whole forest to myself, and lying among the trees on that drowsy August day, with no other sounds than the murmur of insects, it wasn’t hard to find oneself back in that “strange and terrible summer” of 1901. " Source: www.jmbarrie.co.uk/

The Lost Boys was broadcast as a mini-series by the BBC in 1979 and starred Ian Holm (per Bilbo Baggins - The Lord of The Rings : The Fellowship of The Ring).

Mabel Llewellyn, Barrie's housekeeper at Black Lake Cottage, wrote of her excitement at meeting many famous visitors. Here is an extract of her account of a visit by the poet George Meredith (1828 - 1909).

"Other famous visitors were mostly from the literary and artistic world. One of the most welcome ones was the poet George Meredith, then in his seventies, who twice drove over from his home on Box Hill. I was so excited when Mrs Barrie informed me that he was expected, for he was my favourite poet; I especially loved his South-West Wind in the Woodland.

"Mr Barrie had admired Meredith for years and, after travelling out from London to Box Hill, where he sat for hours on the bank opposite Meredith's Flint Cottage – the bank has since been named 'Barrie's Bank' - had become very close friends with him. He was also very special to Mrs Barrie, perhaps because he shared her enthusiasm for her lovely garden.

"Meredith was envious of the Barries because they were surrounded by pine woods. He loved all trees – his cottage was closely bounded on three sides by deciduous woodland, and some of his poems included wonderful descriptions of trees - but pines had a special place in his heart and he loved to walk among them in all weathers. Mrs Barrie clearly thought the white-bearded, eye-twinkling, always laughing Meredith was a charming gentleman. And, from what little I saw of him, so did I. " Source: It Might Have Been Raining - The remarkable story of JM Barrie's housekeeper at Black Lake Cottage. Robert Greenham (grandson of Mabel Llewellyn). Elijah Editions 2005. ISBN 9780955050206

Tilford

Having completed an ungainly inverted S-shaped meander around the site of the abbey, the river heads south before reaching Tilford where it will turn due east. About half a mile upstream from the village is the site of an ancient mill. Close to Sheephatch Lane, Tilford Mill (GR: SU869443) was in business as far back as 1367 when it was a fulling mill for the woollen industry. Further reference to the site as Wanford Mill, then milling corn, was made in 1679. There was an active corn mill here until 1850 with the mill demolished in 1866. Part of the miller’s house survives today as Tilford Mill Cottage. The bridge carrying Sheephatch Lane is named after the mill and is another of the bridges built by the Waverley Abbey monks although centuries of repairs have significantly altered it.

click on image to go to photographer's website

Quintessentially English, the village of Tilford sits on the confluence of the twin Wey rivers downstream from here, and it is at Tilford that the North Branch and the South Branch meet. Boasting an ancient oak tree, a village pub overlooking a village green on which cricket is regularly played each summer, and until recently two medieval bridges, Tilford could easily still be a quiet Victorian backwater.

SWIM ACROSS TO THE SOUTHERN TWIN OF THE RIVER

THE TWO RIVERS JOIN UP - ON TOWARDS GODALMING & THE NAVIGATIONS

© Wey River 2005 - 2012

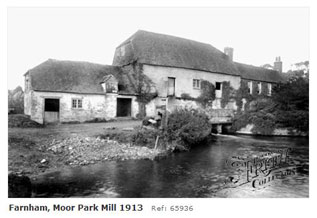

Captioned in Francis Frith archives as 'Moor Park Mill' but believed to be High Mill 1913 Reproduced courtesy of The Francis Frith Collection

Captioned in Francis Frith archives as 'Moor Park Mill' but believed to be High Mill 1913 Reproduced courtesy of The Francis Frith Collection