Border Security and Migration: A Report from Arizona - WOLA (original) (raw)

By Adam Isacson and Maureen Meyer, Senior Associates, and Ashley Davis, Program Assistant

Since 2011, WOLA staff have carried out research in six different zones of the U.S.-Mexican border as part of our migration and border security program. In November, WOLA visited Tucson and Nogales in Arizona, and then crossed to Nogales in Sonora, Mexico. We sought an update on the border security situation; changes in patterns of migration, violence, and crime; concerns about migrants’ humanitarian situation; and evaluations of U.S. and Mexican authorities’ responses to these challenges.

We spoke to law enforcement and migration officials, non-governmental analysts and activists, migrant shelter managers and employees, journalists, ranchers, and forensic anthropologists. This report summarizes what we saw and heard, explains what we think is working, and recommends changes to U.S. and Mexican government policies and strategies.

| Key Findings: The number of apprehended migrants likely increased by about 15 percent nationwide between 2012 and 2013, jumping back over 400,000 for the first time since 2010. That increase mostly happened outside Arizona, and most—perhaps all—of the additional apprehended migrants came from Central America. The apprehension rate, or the number of migrants Border Patrol apprehends versus the number that make it through, is likely lower than previously thought. Recent tests of new technology, and assessments from ranchers and others who work in the border zone, cast doubt on the 87 percent rate that Border Patrol reported for Tucson in 2011. Migrants continue to be deported to Nogales in the middle of the night despite security concerns. According to numerous accounts, abuses against migrants by U.S. and Mexican officials continue to be common. Increased border security has not led to a drop in the amount of drugs crossing the border. Officials say trafficking of methamphetamine, especially in liquid form, is on the rise. The most remote areas of the Arizona border zone have little fencing or Border Patrol coverage. While the cost of providing such coverage would be prohibitive, those who live in these gaps, especially ranchers, say they are unprotected. Every year, hundreds of migrants who cross through these remote zones die of dehydration and exposure. The number of remains found in the Arizona desert in 2013 is similar to previous years and still alarmingly high. Efforts to identify remains and return them to family members face unnecessary administrative obstacles. | Topics: Introduction Migration Migrant Smuggling, Organized Crime, and Drugs Migrant Deaths Deportation Practices Abuse of Migrants Use of Force and Fatal Incidents Recommendations |

|---|

|

|---|

| Border counties in the Tucson Sector. |

Introduction

Of the nine sectors into which U.S. Border Patrol divides the border with Mexico, Tucson—which comprises the easternmost 72 percent of Arizona—has been the busiest during the past decade. It has seen the largest number of undocumented migrants, the highest number of border-zone drug seizures (28 percent in 2011, the latest data available), the greatest number of recovered remains of migrants who perish in extreme desert conditions, and the largest number of Border Patrol agents: 4,176 or 23 percent of all Border Patrol personnel stationed at the U.S.-Mexico border in 2012.

In the Tucson sector, Border Patrol works out of eight stations and seven “forward operating bases,” or rustic facilities located in very remote areas. In order to improve coordination, the Tucson sector and the Yuma sector to the west (which incorporates a sliver of southeastern California) are under the direction of a “Joint Field Command,” whose chief ranks above both sector chiefs. Hundreds of officials from the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Office of Field Operations (OFO), meanwhile, manage six ports of entry, or official land border crossings. CBP’s Office of Air and Marine manages several aircraft from airstrips in Tucson and Sierra Vista; the latter base also houses four Predator-B drones that fly constantly over the border zone. Officials say that the 2013 Budget Control Act did not affect their operations significantly; cutbacks in man-hours were mostly felt in “lower risk” areas within the sector.

Tucson was not always this busy. Through the 1990s, far more illegal cross-border traffic entered near larger cities like San Diego and El Paso. Southern Arizona, with its inhospitable deserts, would not be a migrant’s or smuggler’s first choice. Terrain is treacherous, water is hard to come by, wild animals threaten, and temperatures can reach over 120 degrees Fahrenheit during the day in the summer months, and quickly drop below freezing at night during the winter. In the 1990s, though, Border Patrol cracked down on cross-border traffic in San Diego and El Paso with operations “Hold the Line” and “Gatekeeper.” New fencing and greatly increased patrols in those zones ended up funneling much illegal cross-border traffic into Arizona’s deserts. There, the harsh climate and terrain did not deter would-be border crossers, and the Tucson sector became the most heavily traveled, and trafficked, of all nine sectors.

The official response came amid the mid-2000s buildup that doubled Border Patrol and paid for hundreds of miles of new fencing. A large investment increased the U.S. law enforcement, intelligence, and military presence in the Tucson sector. As new Border Patrol agents underwent training and new sensing and surveillance technologies went online, the Bush and Obama administrations added two large deployments of National Guard soldiers, which have almost completely wound down today.

Currently, although attempted migration has reduced significantly from the mid- to late 2000s, the Tucson sector remains a principal route for northbound migrants and drug and human traffickers. 2013 data may, however, show it being overtaken by the southernmost part of Texas, the Border Patrol’s Laredo and Rio Grande Valley sectors, which have experienced a sharp growth in arrivals of migrants from Central America. (See our January 2013 report on south Texas.)

Migration

Border Patrol estimates migrant flows by counting the number of undocumented migrants it apprehends in its zone of operations, within 100 miles of the border. It keeps track of these apprehensions according to the U.S. government’s fiscal years—so for its purposes, 2013 ended on September 30th. According to preliminary data, Border Patrol officials told us the number of apprehended migrants likely increased by 15 percent nationwide between 2012 and 2013, jumping back above 400,000 for the first time since 2010. Though details are not yet available, most of that increase appears to have taken place in south Texas, and probably involved mostly Central American citizens. The number of apprehended Mexican citizens likely stayed the same or even decreased.

In the Tucson sector, Border Patrol officials told us that apprehensions rose by about one percent in 2013, to a total in the low 120,000s. In 2011, Border Patrol estimated that it had apprehended or turned back 87 percent of border crossers in the Tucson sector. Several non-governmental experts and ranchers we interviewed reject that estimate, though, citing a belief that apprehensions and “turn-backs” combined may be less than 50 percent, and alleging that many more migrants and traffickers make it through.

This view appeared to be confirmed by a late 2012 and early 2013 test of a new radar surveillance technology, known as VADER. Between October and December 2012, CBP mounted this sophisticated system, borrowed from the U.S. Army, on unmanned aircraft flown along the Arizona border. The sensor identified 1,800 migrant crossers that Border Patrol agents captured, but also revealed 1,962 others who got away, hinting at an apprehension rate of roughly 47 percent.

In 2012, about 15 percent of the migrants Border Patrol apprehended in the Tucson sector came from countries other than Mexico, principally from Central America. This is a far lower share than in south Texas—closer to the main sending countries of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador—where over half of apprehended migrants in 2012 were from Central America.

Still, the number of Central American migrants coming all the way to Arizona appears to be rising. We heard the same on the Mexican side, from workers at the Kino Border Initiative aid center that serves migrants, and from officials of the Grupo Beta, the unit of the Mexican government’s National Migration Institute (INM, Instituto Nacional de Migración) charged with migrant search, rescue, and first aid. In Nogales, Mexico, most migrants availing themselves of these organizations’ services were either Central Americans coming northward for the first time, or some of the tens of thousands of deported Mexican migrants whom U.S. authorities drop off at Nogales, Mexico’s downtown port of entry every year (29,807 through September 2013; 45,177 in all of 2012).

U.S. officials noted that 2012 and the first half of 2013 also saw a rise in arrivals of migrants from India. After undergoing a long multi-stage journey organized by a network of smugglers, the Indian migrants usually report to U.S. authorities at Nogales’s two ports of entry, where they declare their intention to apply for asylum, typically citing religious persecution in their homeland. The number of Indian arrivals has decreased since spring of 2013, officials from Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) told us, due to agencies improving their information sharing about smuggling networks.

A minority of migrants from Mexico and Central America also seek to enter the United States through ports of entry, using forged documents or hiding in vehicles. Most, however, attempt to cross in the dangerous desert between border towns. One of the largest corridors of migrant flows begins about four miles west of Nogales, where the 18-foot-tall steel border fence that divides the city gives way to a 94.2 mile combination of four-strand barbed wire and “Normandy-style” vehicle barriers.

| View the video “The U.S.-Mexico border fence, viewed from Nogales, Mexico” |

|---|

|

| Two views of the Tucson sector border fence. At top, in downtown Nogales, Sonora, looking north. At bottom, on the lands of rancher Jim Chilton near Arivaca, Arizona. (Photo courtesy of Mr. Chilton.) |

Further west, on the other side of the town of Sasabe, Arizona, the line between the two countries enters the lands of the Tohono O’Odham Nation, which incorporate both U.S. and Mexican territory. The Nation’s citizens cross freely between the two countries, but so, increasingly, do traffickers and migrants. Border Patrol carries out patrols in the Tohono O’Odham territory, but according to several non-governmental accounts, its relations with residents are strained, in part because residents are frequently stopped and questioned by Border Patrol agents. (We did not interview leaders or members of the Nation on this trip. U.S. authorities indicated that tribal leaders were welcoming more law-enforcement presence in response to narcotraffickers’ efforts to recruit young people.) The Nation’s rugged, inaccessible lands have seen some of the highest concentrations of human remains, as many migrants perish there. There are currently seven Border Patrol-maintained rescue beacons on the Nation’s land. However, tribal leaders do not allow outside humanitarian workers to install water stations, out of concern that they may encourage still more incursions.

Migrant Smuggling, Organized Crime, and Drugs

This corridor is most easily approached from the Sonora town of El Altar, where migrant smuggling is a big business—albeit reduced from the mid- to late 2000s, when the number of migrants attempting to cross here was a multiple of what is today. “Polleros” or “coyotes,” paid guides who promise to accompany migrants through the desert to an arranged pick-up point inside the United States, routinely charge US$3,000 or more for their services. This has more than tripled in the past two decades as the increased security presence on the U.S. side has raised the probability of getting caught.

Another change in the pollero business has been a full takeover by organized crime. While many of the migrant guides may be the same ones who ran “mom and pop” smuggling operations in the 1980s and 1990s, they cannot operate today without paying a share of their earnings to the organization that controls criminality in this border region.

In Sonora today, that organization is the Sinaloa cartel, also known as the Pacific cartel or the Federation, the loosely organized trafficking network run by most-wanted fugitive Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán. Sinaloa’s dominance of cross-border trafficking now extends from the Pacific port of Tijuana eastward at least to Ciudad Juárez, across from El Paso, Texas.

Its monopoly of drug trafficking and other organized crime, abetted by corrupt ties with local, state, and federal Mexican security forces, has curtailed territorial disputes between traffickers—a key reason why violence levels have dropped significantly along the western half of Mexico’s northern border zone. Everyone we interviewed in Nogales, Sonora, concurred that violence has declined since Sinaloa ejected a Zetas cartel attempt to assume control of drug and migrant trafficking, which was over by 2011.

With violence down on the Mexican side of the border, “spillover” into Arizona has been scarce. Southern Arizona’s counties have in fact experienced double-digit drops in homicides and other violent crime since 2002.

Although violent incidents are infrequent, Arizona border-zone ranchers feel menaced by many of the migrant smugglers and drug traffickers whom they encounter on their lands. They disagree with the Border Patrol’s decision to deploy most of its personnel several miles back from the actual borderline. Ranchers like Jim Chilton, whose property includes leased federal land with 5 1/2 miles of barbed-wire international border fence, say they feel exposed and unprotected.

Less violence has not meant less drug trafficking. U.S. law enforcement officials told us that they had seen no drop in the amount of drugs crossing into the Tucson sector. Most notably, officials said they were seeing a flood of methamphetamine, often in liquid form—the same development that we heard from law enforcement officials in south Texas in late 2012. While little methamphetamine today is produced in the United States, Mexico—especially the state of Michoacán, whose ports receive chemical precursors from Asia—is now U.S. users’ principal source of the drug, and production is growing.

[ ](http://www.wola.or g/files/images/131204%5Fdrugdata.png) ](http://www.wola.or g/files/images/131204%5Fdrugdata.png) |

|---|

| According to a November DEA report, U.S. authorities seized three times more heroin and five times more methamphetamine near the border in 2012 than they did in 2008. |

Law enforcement officials believe that of drugs that take up little space and weight—methamphetamine, cocaine, heroin, MDMA—the majority passes through ports of entry, in passenger vehicles and cargo containers. The majority of heavier, bulkier marijuana transits between the ports of entry, though officials believe that an increasing proportion is traveling inside cargo containers at the ports. Marijuana seizures, roughly a million pounds in Arizona in 2013, were down very slightly from 2012.

Several sources said that criminal groups at times require migrants transiting the desert to carry a load of drugs, often marijuana, with them. There is no good sense of how common this practice is, or whether—as some interviewees suggested—it applies only to those who cannot pay polleros’ steep fees. Some migrants may prefer to bring the illegal load because it offers more certainty of being met by contacts on the U.S. side of the border.

Another transport method is the “circuito,” in which drug couriers—often minors from border towns—bring a load north and return to Mexico. Jim Chilton, the Arivaca-based rancher, told us that after making their drop-off, some couriers surrender themselves to ranchers or Border Patrol in order to get easy transport back to Mexico.

Organized crime groups’ control of illegal cross-border activity is complete, according to numerous testimonies. It is virtually impossible for a migrant to attempt to cross alone or without paying a fee or using a cartel-approved pollero. Though he could not confirm the story, a migrants’ rights defender in Sonora said that for a recent period of more than a week, the cartel had given an order that only drug couriers could cross the border; the result was a temporary halt in migrant flows.

|

|---|

| Tucson is more than 3 days’ walk in the desert from the border, warns a poster from Humane Borders, a Tucson-based organization. |

According to several experts and activists, the influence of organized crime has made polleros more mercenary, often treating the migrants they accompany more like merchandise than human beings. Cases of migrants being robbed by bajadores (bandits) or abandoned in the Arizona desert by their smugglers appeared to be growing more frequent. In other cases, groups of migrants were unwittingly being used as decoys: as Border Patrol apprehends them, drug couriers take advantage of the distraction and slip past.

In some cases, polleros or kidnappers hold groups of migrants for ransom in “safe houses,” often under subhuman conditions, in order to extract money from relatives, many of whom live in the United States. These safe houses are usually in Mexico, though cases have occurred as far north as Phoenix. This crime rarely gets reported, and Sonora has not seen migrant massacres like the horrific scenes that have taken place further east, in the Mexican states of Tamaulipas and Nuevo León.

As a result, nobody whom we interviewed had a good sense of how frequent or widespread migrant kidnappings are today in Sonora, although they did point to criminal groups’ collusion with authorities as a factor that may inhibit investigations into kidnapping rings or safe houses’ locations. It is likely, though, that by the time they get to Sonora, northbound Central American migrants have already suffered the worst of the assaults, robberies, sexual violence, and other crimes that they will encounter at the hands of criminals and corrupt members of the security forces, principally the federal, state, and municipal police.

Migrant Deaths

Once migrants cross into Arizona, the risk of injury or death remains high but the cause is less likely to be human. The desert is deadly: dehydration, heat exposure, and hypothermia claim hundreds of lives on U.S. soil each year. Since 1998, the Tucson sector has accounted for 38 percent of all migrant human remains found in wilderness zones north of the border. Tucson still led all nine Border Patrol sectors in this grisly statistic in 2012, with 177 remains found, though the Rio Grande Valley sector in southeast Texas, where authorities have been caught unprepared for a wave of Central American migrants, has also seen a significant increase in deaths.

A similar number of bodies appear to have been found in 2013 in Arizona, but not all may have perished this year. According to the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner, it is difficult to know whether the high number of remains found this year reflects an increase in migrant deaths or whether Border Patrol agents and others are simply finding more remains of migrants who had died in previous years.

Organizations in Tucson and Nogales, Mexico report that migrants frequently talk about seeing the remains of other migrants during their journey through the desert. These organizations, and representatives of the Grupo Beta, also report that few migrants are prepared for their journey. Smugglers frequently claim that a three to five day journey will take only a few hours. Migrants do not have appropriate shoes and clothing, and everyone we spoke to commented on the impossibility of carrying enough water for the long journey.

|

|---|

|

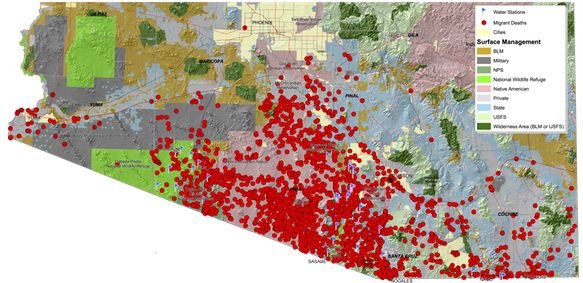

| Top: the Tucson-based organization Humane Borders maps locations where remains of 2,471 migrants have been found in Arizona’s deserts between October 1999 and June 2013. Bottom: Of all remains found on the U.S. side of the border since 1998, 40 percent have been in the Tucson sector. Border-wide, 2012 was the second-worst year of the past 15. |

Several humanitarian groups in southern Arizona routinely leave water for migrants in the desert. Some ranchers have also installed drinking fountain valves in their cattle water troughs for migrants to use, and carry water jugs in their trucks in case they encounter migrants in distress on their lands. Similarly, Border Patrol in the Tucson sector reported a 37 percent increase in rescues of migrants in distress between 2012 and 2013. Some were migrants taking advantage of 22 rescue beacons that Border Patrol has installed throughout the sector’s 90,000 square miles. Even more appeared to be benefiting from improvements in mobile phone coverage: 911 calls are leading to an increasing number of rescues.

Nonetheless, the number of remains still being found indicates that search and rescue efforts are falling short. With such vast and hostile terrain, migrants continue to get lost, are abandoned by smugglers when they are injured or in distress, and die in the desert. Resource deficits and bureaucratic obstacles continue to frustrate efforts to identify migrant remains and match them with relatives in Mexico and Central America.

|

|

|---|---|

| The Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office has files on the remains of every migrant found, and lockers full of items that they were carrying with them when they died. |

As of early November 2013, the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner had 871 cases of unidentified remains, some dating back to the late 1990s. During this same period, the Missing Migrant Project of the Colibri Center for Human Rights has received over 1,700 reports of migrants who are missing. The Office of the Medical Examiner processes the remains, including DNA sampling, for all who are found in Pima, Cochise, Santa Cruz, and Pinal counties, as well as those found on the Tohono O’odham Nation.

Because there are currently no federal funds to process and identify these remains, if the remains are found outside of Pima County, the county where they are found must pay Pima County for processing the remains. This averages around $2,000 for each case—a significant expense for areas with high numbers of migrant deaths, particularly the Tohono O’odham Nation.

Since 2010, agreements between the governments of El Salvador, Honduras, and the Mexican state of Chiapas; the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF, Equipo Argentino de Antropología Forense); and committees of migrant families and organizations have resulted in the creation of National Forensic Databases, and a state database in the case of Chiapas. This allows missing migrants’ family members to submit background and physical data, as well as DNA samples, to be processed and compared with all of the samples of recovered remains that the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner processes. The EAAF has also worked with the Guatemalan government and organizations in Guatemala on cases and is close to starting two additional databases. Thanks to these efforts, 22 matches have been made since 2011 in Arizona, providing closure to Central American and Mexican families who were left wondering what had happened to their loved ones. The EAAF’s work throughout the U.S. border and in Mexico has resulted in a total of 59 identifications since 2011.

When a Mexican migrant’s remains are found, the identification process is more complex. While the EAAF is taking DNA samples of families in Chiapas, families in most other Mexican states must go through the Mexican Secretary of Foreign Affairs (SRE, Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores). Mexican Consulate representatives in Tucson informed us that families wishing to submit samples of DNA to check for possible matches are required to go to the SRE delegation located in each Mexican state capital and other primary cities, and if the family member is based in the United States, the samples can be taken through one of the 50 consulates. While this is an important service, experts interviewed by WOLA expressed concerns that the Mexican government does not compare DNA samples from family members with the DNA of unidentified remains from Pima County without a strong reason to believe that a match exists with a specific set of recovered remains. The Mexican government has the capacity to do large-scale crossings of the family profiles in the government’s national DNA database with the unidentified remains that have been processed by the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner, but this does not appear to be happening. This inhibits the automatic comparison of family DNA samples with any new remains that are discovered.

Apart from work being done to identify the remains of missing migrants through DNA analysis, the Missing Migrant Project has made dozens of identifications of migrant remains non-genetically, such as based on belongings found with the remains, distinct markings like tattoos, or dental records.

Deportation Practices

In 2009, the Mexican government launched the Humane Repatriation Program, installing offices to receive migrants in some of Mexico’s main border cities, including one in downtown Nogales, on the Sonora side of the DeConcini Port of Entry. There, several times each day, a doorbell rings. This means that a van or bus has pulled up on the U.S. side of the crossing and ICE or Border Patrol unload from a few to a few dozen Mexican citizens, remove their restraints, and hand them over to the Mexican authorities.

|

|---|

| A Mexican migration official awaits the arrival of a vanload of deportees being brought from the U.S. side of the downtown Nogales port of entry. |

Looking dazed, with laces removed from their shoes and their belongings often in plastic bags bearing the Homeland Security logo, the Mexican deportees—men, women, and children—are led to the small INM facility on the Mexican side of the crossing. There, they may receive first aid through the Red Cross, a snack, and a briefing about the few services available to them and the safety risks they might face. (Advice includes “the shelter may offer you a place to sleep for three days,” “be careful not to let anyone see money you are carrying,” and “do not let others overhear your phone conversations.”) In Nogales, there are three shelters for migrants, a specific shelter for vulnerable migrant women and children, plus two food banks (comedores) that provide migrants with meals, medical assistance, and clothing.

Officials enter the deportees’ identification information into a database, and—in the case we witnessed, less than 15 minutes after being handed over—they are free to walk with their bag of belongings out into the streets of Nogales, a city that many have likely never seen before. Here, they risk falling prey to thieves, corrupt police, and even kidnappers.

|

|---|

| A recently deported migrant’s belongings in a CBP-issued bag. |

The risk is far greater when the deportations occur in the middle of the night, a practice that U.S. agencies inexplicably continue to carry out in Nogales and at many other ports of entry. According to Mexican immigration officials, Monday through Friday, at any time between 2:00 a.m. and 4:00 a.m., a bus regularly arrives at the DeConcini Port of Entry with a load of migrants coming from detention centers throughout the state. Mexican officials affirmed that there were fewer cases of “persons with special needs,” such as women traveling alone or with children, or unaccompanied minors, being deported at night, a practice that violates bilateral repatriation agreements and which U.S. authorities frequently breached in the past.

Although current agreements permit night deportations for many migrants, particularly men, deporting any migrant at night presents several concerns. Numerous migrants arrive in inappropriate clothing for the cold night temperatures in Nogales. They are easily identifiable because of their clothing and the DHS bags they often carry. There are few places a migrant can go in these hours as the shelter is closed or inaccessible. While we were told that some migrants pool together money to stay in a hotel, others end up on the street, waiting for the morning and the possibility of a warm meal, making them vulnerable to criminals or corrupt officials.

Despite these risks, we were unable to obtain an explanation for U.S. agencies’ continued insistence on this practice, when they are clearly able to wait a few hours before dropping off many female and minor deportees.

While Nogales was once one of the top cities receiving repatriated migrants, this trend has shifted in recent years, with deportations dropping over 70 percent since 2008. In contrast to other sectors, U.S. officials laterally repatriate migrants detained in Arizona to border cities that are distant from their original crossing points, but no migrant is laterally repatriated to the border towns across from the Tucson sector. This repatriation is carried out through the Alien Exit Transfer Program (ATEP). As part of the Border Patrol’s “consequence delivery system,” ATEP is designed to disrupt migrants’ connections to their original smugglers by repatriating them to another part of the border.

In fact, ATEP appears to increase the odds of a migrant deciding to cross the border again. According to a May 2013 Congressional Research Service report, the recidivism rate for ATEP was 23.8% in 2012—meaning about one-quarter of migrants deported through ATEP were later captured trying to re-enter the United States. This is a higher rate of recidivism than those measured for any other consequence delivery method apart from voluntary return.

The Tucson sector repatriates dozens of male migrants through ATEP every day, with two buses going west to Mexicali, Baja California and at least one bus going to Ciudad Acuña in Coahuila. U.S. authorities affirm that they coordinate closely with the Mexican government in this program, and indeed we were told that the Mexican consulate always has access to these migrants and is able to interview them, especially those going east to Ciudad Acuña.

That migrants are being deported on a daily basis to Ciudad Acuña, a tiny border city with few services, is troubling, especially as violent crime rates there have continued to increase. Because only male migrants can be laterally repatriated, this program can lead to family separation. Local shelters have reported many cases where female migrants are deported to the closest border city while their spouses, brothers, or other male traveling companions are transferred to another part of the border hundreds of miles away.

|

|---|

| The Kino Border Initiative food bank (comedor) serves migrants, most of them deportees, in Nogales, Mexico. |

Another concern we encountered is that migrants are frequently deported without all of their belongings, including identification documents, which they were carrying when they were apprehended. While explanations vary, the failure to return belongings seems more prevalent when a migrant has been transferred to several different detention facilities and has been in the custody of different U.S. agencies, since each agency has a different policy for which belongings migrants are allowed to keep with them. Mexican officials told us of several containers of migrants’ unclaimed belongings that are in Border Patrol’s possession, and of their efforts to return these belongings to migrants or their family members. A University of Arizona survey of over 1,100 deported Mexican migrants found 39 percent reported having property taken from them and not returned. In a recently released policy brief, the researchers report that the number for the Tucson sector is 31 percent.

Not having an ID makes it very difficult for a migrant to access government services or to do something as simple as cash a check. Because municipal police officers know that many migrants do not have their documents, they frequently ask them for their papers, alleging that it is a crime not to have an ID, and extort them, demanding money to avoid going to jail. Cashing checks appeared to be another problem, particularly for migrants coming from county jails in the United States. In these cases, we were told the migrants are issued checks for the cash that they had been carrying when they were detained. The checks can only be cashed in the United States, creating many obstacles for migrants who are deported to Mexico, where they are subjected to high processing fees or theft by scam artists.

“Operation Streamline,” a 2005 program designed to criminally prosecute illegal entry in order to deter migrants, continues in Tucson with 60-65 migrants sentenced to prison per day. There are many concerns about the program’s impact on immigrant families with mixed legal status, and the failure to ensure due process guarantees and adequate legal representation of the migrants. The sheer number of migrants processed through Streamline also requires significant federal court and enforcement resources that would be better used to focus on more serious criminal prosecutions.

Abuse of Migrants

Mexican migrants we met in Nogales, Sonora, spoke of different forms of abuse while in Border Patrol custody, such as inadequate privacy when using the restroom during detention, verbal abuse, being separated from family members, being hit with a rock by an agent, and bites from patrol dogs.

These stories of abuse are consistent with findings by other groups, including the Arizona-based organization No More Deaths, which has extensively documented abuse and mistreatment of migrants since 2006. In their latest report from September 2011, A Culture of Cruelty, No More Deaths found that of the 12,895 migrants they interviewed for their study, nearly ten percent reported some form of mistreatment by Border Patrol, including physical, verbal and psychological abuse; inhumane processing center conditions; and separation of family members.

Another form of abuse takes place further away from the border in roving patrol stops, in which Border Patrol agents pull over and search vehicles if they suspect the motorist to have violated immigration laws. Border Patrol has the authority to conduct such warrantless searches within 100 miles from any border, and the practice has led to many complaints of abuse from migrants and citizens alike. Motorists have reported being forcibly removed from their cars, threatened, pushed, and having their belongings or vehicle damaged by agents.

Recently, The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) presented a case from May 2013, in which a Tucson resident, Clarisa Christianson, was stopped approximately 60 miles north of the border as she was driving home from school with her children. When she demanded an explanation for why she had been stopped, the agents reached inside her car to turn off her ignition, threatened her with a Taser, threatened to cut her out of her seatbelt with a knife, and then slashed her tire, leaving her and her children stranded on the road.

In Mexico, Mexican and Central American migrants also reported being abused by authorities, including many accounts of extortion when their buses or other vehicles encountered checkpoints on the highways around Nogales.

The Central Americans whom we met were reluctant to speak about what happened in Mexico, except to say that it was “very bad.” The little that we were told was from one Salvadoran migrant, fleeing extortion by maras, who spoke of being extorted by Mexican Federal Police agents at a checkpoint in southern Mexico and forced to give them all of his money—$2,500—in exchange for not turning him over to immigration authorities. A Honduran migrant spoke of criminal presence on the trains that many migrants ride north, where groups force riders to pay a fee, and in many cases beat those who cannot pay or throw them off the train. He spoke of a criminal in central Mexico known as the “lord of the trains” (el señor de los trenes) because of his control over that section of the route.

Use of Force and Fatal Incidents

In October 2012, Nogales resident Jose Antonio Elena Rodríguez was killed in downtown Nogales, Mexico when a Border Patrol agent opened fire at a group of people allegedly throwing rocks at him. Rodriguez was shot at least eight times and all but one of the bullets hit him in the back. Since 2010, at least 20 civilians have been killed in confrontations with Border Patrol agents on the U.S.-Mexico border; six of which occurred in the Tucson sector. Many groups, including the Mexican government, have publicly condemned the deadly use of force in these incidents.

In November 2013, the Police Executive Research Forum, a nonprofit group that advises law enforcement, completed a government-commissioned review that recommended Border Patrol agents stop the use of deadly force against rock throwers. CBP, Border Patrol’s parent agency, promptly rejected this recommendation, deeming it “very restrictive” given the unique terrain in which they work.

Recommendations

Based on our findings from this and other research trips, we present the following recommendations on border security and the protection of migrants at the border. We believe that any future efforts to secure our southern border must reflect the reality on the ground and ensure that U.S. enforcement policies do not risk the lives and safety of migrants. The Mexican government should also increase its efforts to protect migrants and assist families in their quest to find loved ones who disappeared while attempting to enter the United States.

- Devote more resources and attention to ports of entry, where wait times are long, understaffing is most severe, and much contraband passes through. While recent construction at Nogales’s Mariposa port of entry is positive, the four crossings in Arizona’s smaller, remoter cities are reportedly outdated and outmoded, although they probably see a great deal of drug traffic.

- Increase southbound checks for cash and arms. It is positive that the Mariposa port of entry construction will include a new facility for southbound checks. But Arizona’s many gun shops and gun shows remain very easy places for a straw purchaser to buy a gun.

- Install more rescue beacons in the Tucson sector to increase the possibility of assisting migrants in distress and preventing further deaths.

- Halt all night deportations, which unnecessarily endanger repatriated migrants.

- Return migrants’ confiscated belongings. This is an administrative issue that could be fixed with better record keeping, such as by creating a shared database, and harmonizing policies and standards for handling migrant belongings. Migrants should not have their cash refunded in the form of checks that are difficult to collect outside the United States.

- Customs and Border Protection should emphasize training on de-escalation techniques on the use of force, and provide additional non-lethal options for its agents.

- The Mexican government should standardize the DNA sampling process from relatives of missing persons, compare these samples with their own DNA database of unidentified remains, and facilitate comparisons of DNA samples taken from migrant families with all of the remains being recovered in Arizona and in other border states.

- The Mexican government should investigate and sanction police involved in extortion and other abuses against migrants, as well as third parties involved in kidnappings and other attacks against migrants.