Kwame Nkrumah (original) (raw)

| Kwame Nkrumah | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Kwame Nkrumah on a Soviet postage stamp | |

| 3rd Chairman of the Organization of African Unity | |

| In office21 October 1965 – 24 February 1966 | |

| Preceded by | Gamal Abdel Nasser |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Arthur Ankrah |

| 1st President of Ghana | |

| In office1 July 1960 – 24 February 1966 | |

| Preceded by | William Hare, 5th Earl of Listowel as Governor-General |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Arthur Ankrah as Chairman of the National Liberation Council |

| 1st Prime Minister of Ghana | |

| In office6 March 1957 – 1 July 1960 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Governor General | Sir Charles Noble Arden-Clarke until 24 June 1957 Lord Listowel 24 June 1957 - 1 July 1960 |

| Preceded by | Office Established |

| Succeeded by | Himselfas President of Ghana |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 21 September 1909(1909-09-21) Nkroful, Gold Coast |

| Died | 27 April 1972(1972-04-27) (aged 62) Bucharest, Romania |

| Nationality | British, Ghanaian |

| Political party | Convention People's Party |

| Spouse(s) | Fathia Rizk |

| Children | Francis, Gamal, Edward, Samia and Sekou |

| Profession | Lecturer |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

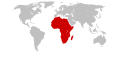

Kwame Nkrumah (21 September 1909 – 27 April 1972)[1] was the leader of Ghana and its predecessor state, the Gold Coast, from 1952 to 1966. Overseeing the nation's independence from British colonial rule in 1957, Nkrumah was the first President of Ghana and the first Prime Minister of Ghana. An influential 20th century advocate of Pan-Africanism, he was a founding member of the Organization of African Unity and was the winner of the Lenin Peace Prize in 1963.

Contents

- 1 Early life and education

- 2 Return to the Gold Coast

- 3 Independence

- 4 Politics

- 5 Economics

- 6 Decline and fall

- 7 Exile, death and tributes

- 8 Works by Kwame Nkrumah

- 9 See also

- 10 References

- 11 Further reading

- 12 External links

Early life and education

In 1909, Kwame Nkrumah was born to Madam Nyaniba[2][3] in Nkroful, Gold Coast.[4][5] Nkrumah graduated from the Achimota School in Accra in 1930,[1] studied at a Roman Catholic seminary, and taught at a Catholic school in Axim. In 1935 he left Ghana for the United States, receiving a BA from Lincoln University, Pennsylvania in 1939, where he pledged the Mu Chapter of Phi Beta Sigma fraternity, and received a Bachelor of Sacred Theology in 1942. Nkrumah earned a Master of Science in education from the University of Pennsylvania in 1942, and a Master of Arts in philosophy the following year. While lecturing in political science at Lincoln he was elected president of the African Students Organization of America and Canada. As an undergraduate at Lincoln he participated in at least one student theater production and published an essay on European government in Africa in the student newspaper, The Lincolnian.[6]

During his time in the United States, Nkrumah preached at black Presbyterian Churches in Philadelphia and New York City.[_citation needed_] He read books about politics and divinity, and tutored students in philosophy. Nkrumah encountered the ideas of Marcus Garvey and in 1943 met and began a lengthy correspondence with Trinidadian Marxist C.L.R. James, Russian expatriate Raya Dunayevskaya, and Chinese-American Grace Lee Boggs, all of whom were members of a US based Trotskyist intellectual cohort. Nkrumah later credited James with teaching him 'how an underground movement worked'.

He arrived in London in May 1945 intending to study at the LSE.[_citation needed_] After meeting with George Padmore, he helped organize the Fifth Pan-African Congress in Manchester, England. Then he founded the West African National Secretariat to work for the decolonization of Africa. Nkrumah served as Vice-President of the West African Students' Union (WASU).

Return to the Gold Coast

In the autumn of 1947, Nkrumah was invited to serve as the General Secretary to the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) under Joseph B. Danquah.[7] This political convention was exploring paths to independence. Nkrumah accepted the position and sailed for the Gold Coast. After brief stops in Sierra Leone, Liberia, and the Ivory Coast, he arrived in the Gold Coast in December 1947.

In February 1948, police fired on African ex-servicemen protesting the rising cost of living. The shooting spurred riots in Accra, Kumasi, and elsewhere. The government suspected the UGCC was behind the protests and arrested Nkrumah and other party leaders. Realizing their error, the British soon released the convention leaders. After his imprisonment by the colonial government, Nkrumah emerged as the leader of the youth movement in 1948.

After his release, Nkrumah hitchhiked around the country. He proclaimed that the Gold Coast needed "self-government now", and built a large power base. Cocoa farmers rallied to his cause because they disagreed with British policy to contain swollen shoot disease. He invited women to participate in the political process at a time when women's suffrage was new to Africa. The trade unions also allied with his movement. By 1949, he organized these groups into a new political party: The Convention People's Party.

The British convened a selected commission of middle class Africans to draft a new constitution that would give Ghana more self-government. Under the new constitution, only those with sufficient wage and property would be allowed to vote. Nkrumah organized a "People's Assembly" with CPP party members, youth, trade unionists, farmers, and veterans. They called for universal franchise without property qualifications, a separate house of chiefs, and self-governing status under the Statute of Westminster 1931. These amendments, known as the Constitutional Proposals of October 1949, were rejected by the colonial administration.

When the colonial administration rejected the People's Assembly's recommendations, Nkrumah organized a "Positive Action" campaign in January 1950, including civil disobedience, non-cooperation, boycotts, and strikes. The colonial administration arrested Nkrumah and many CPP supporters, and he was sentenced to three years in prison.

Facing international protests and internal resistance, the British decided to leave the Gold Coast. Britain organized the first general election to be held under universal franchise on 5–10 February 1951. Though in jail, Nkrumah's CPP was elected by a landslide taking 34 out of 38 elected seats in the Legislative Assembly. Komla Agbeli Gbedemah is credited with organizing Nkrumah's entire campaign while he (Nkrumah) was still in prison at Fort James[8]. Nkrumah was released from prison on 12 February, and summoned by the British Governor Charles Arden-Clarke, and asked to form a government on the 13th. The new Legislative Assembly met on 20 February, with Nkrumah as Leader of Government Business, and E.C. Quist as President of the Assembly. A year later, the constitution was amended to provide for a Prime Minister on 10 March 1952, and Nkrumah was elected to that post by a secret ballot in the Assembly, 45 to 31, with eight abstentions on 21 March. He presented his "Motion of Destiny" to the Assembly, requesting independence within the British Commonwealth "as soon as the necessary constitutional arrangements are made" on 10 July 1953, and that body approved it.

Independence

Nkrumah and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

As a leader of this government, Nkrumah faced many challenges: first, to learn to govern; second, to unify the four territories of the Gold Coast; third, to win his nation’s complete independence from the United Kingdom. Nkrumah was successful at all three goals. Within six years of his release from prison, he was the leader of an independent nation.

At 12 a.m. on 6 March 1957, Nkrumah declared Ghana independent. He was hailed as the Osagyefo - which means "redeemer" in the Twi language.[9]

On 6 March 1960, Nkrumah announced plans for a new constitution which would make Ghana a republic. The draft included a provision to surrender Ghanaian sovereignty to a Union of African States. On 19, 23, and 27 April 1960 a presidential election and plebiscite on the constitution were held. The constitution was ratified and Nkrumah was elected president over J. B. Danquah, the UP candidate, 1,016,076 to 124,623.

In 1961, Nkrumah laid the first stones in the foundation of the Kwame Nkrumah Ideological Institute created to train Ghanaian civil servants as well as promote Pan-Africanism. In 1964, all students entering college in Ghana were required to attend a two-week "ideological orientation" at the Institute.[10] Nkrumah remarked that "trainees should be made to realize the party's ideology is religion, and should be practiced faithfully and fervently." [11]

In 1963, Nkrumah was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize by the Soviet Union. Ghana became a charter member of the Organization of African Unity in 1963.

The Gold Coast had been among the wealthiest and most socially advanced areas in Africa, with schools, railways, hospitals, social security and an advanced economy. Under Nkrumah’s leadership, Ghana adopted some socialist policies and practices. Nkrumah created a welfare system, started various community programs, and established schools.

Politics

He generally took a non-aligned Marxist perspective on economics, and believed capitalism had malignant effects that were going to stay with Africa for a long time. Although he was clear on distancing himself from the African socialism of many of his contemporaries, Nkrumah argued that socialism was the system that would best accommodate the changes that capitalism had brought, while still respecting African values. He specifically addresses these issues and his politics in a 1967 essay entitled "African Socialism Revisited":

Billboard in Zambia with Nkrumah's non-alignment quote: "We face neither East nor West; We face forward" (Taken in May 2005)

"We know that the traditional African society was founded on principles of egalitarianism. In its actual workings, however, it had various shortcomings. Its humanist impulse, nevertheless, is something that continues to urge us towards our all-African socialist reconstruction. We postulate each man to be an end in himself, not merely a means; and we accept the necessity of guaranteeing each man equal opportunities for his development. The implications of this for socio-political practice have to be worked out scientifically, and the necessary social and economic policies pursued with resolution. Any meaningful humanism must begin from egalitarianism and must lead to objectively chosen policies for safeguarding and sustaining egalitarianism. Hence, socialism. Hence, also, scientific socialism."[12]

Nkrumah was also perhaps best known politically for his strong commitment to and promotion of Pan-Africanism. He was inspired by the writings of black intellectuals like Marcus Garvey, W. E. B. Du Bois, and George Padmore, and his relationships with them. Nkrumah's biggest success in this area was perhaps his significant influence in the founding of the Organization of African Unity.

Economics

Nkrumah attempted to rapidly industrialize Ghana's economy. He reasoned that if Ghana escaped the colonial trade system by reducing dependence on foreign capital, technology, and material goods, it could become truly independent. However, overspending on capital projects caused the country to be driven deeply into debt—estimated as much as $1 billion USD by the time he was ousted in 1966.

Decline and fall

The year 1954 was a pivotal year during the Nkrumah era. In that year's independence elections, he tallied some of the independence election vote. However, that same year saw the world price of cocoa rise from £150 to £450 per ton. Rather than allowing cocoa farmers to maintain the windfall, Nkrumah appropriated the increased revenue via federal levies, then invested the capital into various national development projects. This policy alienated one of the major constituencies that helped him come to power.

In 1958 Nkrumah introduced legislation to restrict various freedoms in Ghana. After the Gold Miners' Strike of 1955, Nkrumah introduced the Trade Union Act, which made strikes illegal. When he suspected opponents in parliament of plotting against him, he wrote the Preventive Detention Act that made it possible for his administration to arrest and detain anyone charged with treason without due process of law in the judicial system. Prisoners were often held without trial, and their only legal method of recourse was personal appeal to Nkrumah himself.

When the railway workers went on strike in 1961, Nkrumah ordered strike leaders and opposition politicians arrested under the Trade Union Act of 1958. While Nkrumah had organized strikes just a few years before, he now opposed industrial democracy because it conflicted with rapid industrial development. He told the unions that their days as advocates for the safety and just compensation of miners were over, and that their new job was to work with management to mobilize human resources. Wages must give way to patriotic duty because the good of the nation superseded the good of individual workers, Nkrumah's administration contended.

The Detention Act led to widespread disaffection with Nkrumah’s administration. Some of his associates used the law to arrest innocent people to acquire their political offices and business assets. Advisers close to Nkrumah became reluctant to question policies for fear that they might be seen as opponents. When the clinics ran out of pharmaceuticals, no one notified him. Some people believed that he no longer cared. Police came to resent their role in society, particularly after Nkrumah superseded most of their duties and responsibilities with his personal guard - the National Security Service and presidential Guard regiments. Nkrumah disappeared from public view out of a fear of assassination following multiple attempts on his life. In 1964, he proposed a constitutional amendment making the CPP the only legal party and himself president for life of both nation and party. The amendment passed with 99.91 percent of the vote. Observers condemned the vote as "obviously rigged."[13] In any event, Ghana had effectively been a one-party state since independence. The amendment transformed Nkrumah's presidency into a de facto legal dictatorship.

Nkrumah's advocacy of industrial development at any cost, with help of longtime friend and Minister of Finance, Komla Agbeli Gbedema, led to the construction of a hydroelectric power plant, the Akosombo Dam on the Volta River in eastern Ghana. Kaiser Aluminum agreed to build the dam for Nkrumah, but restricted what could be produced using the power generated. Nkrumah borrowed money to build the dam, and placed Ghana in debt. To finance the debt, he raised taxes on the cocoa farmers in the south. This accentuated regional differences and jealousy. The dam was completed and opened by Nkrumah amidst world publicity on 22 January 1966.

Political cartoon appearing the day after Nkrumah's overthrow.

Nkrumah wanted Ghana to have modern armed forces, so he acquired aircraft and ships, and introduced conscription.

He also gave military support to anti-government guerrillas in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). In February 1966, while Nkrumah was on a state visit to North Vietnam and China, his government was overthrown in a military coup led by Emmanuel Kwasi Kotoka and the National Liberation Council. Several commentators, such as John Stockwell, have claimed the coup received support from the CIA.[14][15][16]

Exile, death and tributes

Memorial to Kwame Nkrumah in Accra

Nkrumah never returned to Ghana, but he continued to push for his vision of African unity. He lived in exile in Conakry, Guinea, as the guest of President Ahmed Sékou Touré, who made him honorary co-president of the country. He read, wrote, corresponded, gardened, and entertained guests. Despite retirement from public office, he was still frightened of western intelligence agencies. When his cook died, he feared that someone would poison him, and began hoarding food in his room. He suspected that foreign agents were going through his mail, and lived in constant fear of abduction and assassination. In failing health, he flew to Bucharest, Romania, for medical treatment in August 1971. He died of skin cancer in April 1972 at the age of 62.

Accra Memorial Close Up

Nkrumah was buried in a tomb in the village of his birth, Nkroful, Ghana. While the tomb remains in Nkroful, his remains were transferred to a large national memorial tomb and park in Accra.

Over his lifetime, Nkrumah was awarded honorary doctorates by Lincoln University, Moscow State University; Cairo University in Cairo, Egypt; Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland; Humboldt University in the former East Berlin; and many other universities.[_citation needed_]

In 2000, he was voted Africa's man of the millennium by listeners to the BBC World Service.[17]

Works by Kwame Nkrumah

- "Negro History: European Government in Africa," The Lincolnian, 12 April 1938, p. 2 (Lincoln University, Pennsylvania) - see Special Collections and Archives, Lincoln University

- Ghana: The Autobiography of Kwame Nkrumah (1957) ISBN 0-901787-60-4

- Africa Must Unite (1963) ISBN 0-901787-13-2

- African Personality (1963)

- Neo-Colonialism: the Last Stage of Imperialism (1965) ISBN 0-901787-23-X

- Axioms of Kwame Nkrumah (1967) ISBN 0-901787-54-X

- African Socialism Revisited (1967)

- Voice From Conakry (1967) ISBN 90-17-87027-3

- Dark Days in Ghana (1968) ISBN 0-7178-0046-6

- Handbook of Revolutionary Warfare (1968) - first introduction of Pan-African pellet compass ISBN 0-7178-0226-4

- Consciencism: Philosophy and Ideology for De-Colonisation (1970) ISBN 0-901787-11-6

- Class Struggle in Africa (1970) ISBN 0-901787-12-4

- The Struggle Continues (1973) ISBN 0-901787-41-8

- I Speak of Freedom (1973) ISBN 0-901787-14-0

- Revolutionary Path (1973) ISBN 0-901787-22-1

See also

References

- ^ a b E. Jessup, John. An Encyclopedic Dictionary of Conflict and Conflict Resolution, 1945-1996. pp. 533.

- ^ "Rulers - Nkrumah, Kwame". Lists of heads of state and heads of government. Rulers.org. http://rulers.org/indexn2.html#nkrum. Retrieved 2007-03-24.

- ^ Asante Fordjour (6 March 2006). Ghana Home Page.

- ^ "Kwame Nkrumah Biography". Ghana to Ghana The Place for Ghana News and Entertainment. http://www.ghanatoghana.com/Ghanahomepage/kwame-nkrumah-biography-biography-kwame-nkrumah. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ Yaw Owusu, Robert (2005). Kwame Nkrumah's Liberation Thought: A Paradigm for Religious Advocacy in Contemporary Ghana. pp. 97.

- ^ special Collections and Archives, Lincoln University.

- ^ "The Rise And Fall of Kwame Nkrumah". Ghana to Ghana The Place for Ghana News and Entertainment. December 30th, 2010. http://www.ghanatoghana.com/Ghanahomepage/kwame-nkrumah-history-rise-fall-kwame-nkrumah. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ Birmingham, David. Kwame Nkrumah: The Father of African Nationalism (Revised Edition). Ohio University Press. 1998.

- ^ Zimmerman, Jonathan (2008-10-23). "The ghost of Kwame Nkrumah". International Herald Tribune. http://www.iht.com/articles/2008/04/23/opinion/edzimmerman.php. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

- ^ National Reconciliation Commission Report, 2004, pp. 251

- ^ Nkrumah's Deception of Africa. Ghana Ministry of Information. 1967.

- ^ African Socialism Revisited by Kwame Nkrumah 1967

- ^ Anthony, S. (1969) "The State of Ghana" African Affairs Vol. 68, No. 273, pp. 337-339

- ^ Botwe-Asamoah, Kwame. Kwame Nkrumah's Politico-Cultural Thought and Politics: An African-centered Paradigm for the Second Phase of the African Revolution. Page 16.

- ^ Carl Oglesby and Richard Shaull. Containment and Change. Page 105.

- ^ Interview with John Stockwell in Pandora's Box: Black Power (Adam Curtis, BBC Two, 22 June 1992)

- ^ Kwame Nkrumah's Vision of Africa 14 September, 2000

Further reading

- Birmingham, David (1998). Kwame Nkrumah: The Father of African Nationalism. Athens: Ohio University Press. ISBN 0821412426.

- Tuchscherer, Konrad (2006). "Kwame Francis Nwia Kofie Nkrumah". In Coppa, Frank J.. Encyclopedia of Modern Dictators. New York: Peter Lang. pp. 217–220. ISBN 0820450103.

- Davidson, Basil (2007) [1973]. Black Star: A View of the Life and Times of Kwame Nkrumah. Oxford, UK: James Currey. ISBN 9781847010100.

- Mwakikagile, Godfrey (2006). "Nyerere and Nkrumah: Towards African Unity". Nyerere and Africa: End of an Era (Third ed.). Pretoria, South Africa: New Africa Press. pp. 347–355. ISBN 0980253411.

- Poe, D. Zizwe (2003). Kwame Nkrumah's Contribution to Pan-African Agency. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0203505379.

- James, C. L. R. (1982). Nkrumah and the Ghana Revolution. London: Allison & Busby. ISBN 0850314615.

- Defense Intelligence Agency, "Supplement, Kwame Nkrumah, President of Ghana", 12-January-1966.

External links

- Kwame Nkrumah Mausoleum and Museum at Nkroful, Western Region

- Kwame Nkrumah Memorial Park & Museum, Accra

- Ghana-pedia Dr. Kwame Nkrumah

- Ghana-pedia Operation Cold Chop: The Fall Of Kwame Nkrumah

- Dr Kwame Nkrumah

- Excerpt from Commanding Heights by Daniel Yergin and Joseph Stanislaw

- Timeline of events related to the overthrow of Kwame Nkruma

- The Kwame Nkrumah Lectures at the University of Cape Coast, Ghana, 2007

- Kwame Nkrumah Information and Resource Site

- Ghana re-evaluates Nkrumah by The Global Post

- Dr Kwame Nkrumah's Midnight Speech on the day of Ghana's independence – 6 March 1957

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| New title | **Leader of the Convention People's Party**1948–1966 | Succeeded by Parties banned |

| Political offices | ||

| New title | **Prime Minister of the Gold Coast**1952–1957 | Succeeded by Himself as Prime Minister of Ghana |

| Preceded by Himself as Prime Minister of the Gold Coast | **Prime Minister of Ghana**1957–1960 | Succeeded by Himself as President |

| Preceded by Himself as Prime Minister | President of Ghana1960–1966 | Succeeded by Lt. Gen. Joseph A. Ankrah Military Head of State |

| New title | **Foreign Minister**1957–1958 | Succeeded by Kojo Botsio |

| Preceded by Ebenezer Ako-Adjei | **Foreign Minister**1962–1963 | Succeeded by Kojo Botsio |

| New title | Minister for Defence1957–1960 | Succeeded by Charles de Graft Dickson |

| Preceded by Gamal Abdel Nasser | **Chairperson of the Organization of African Unity**1965–1966 | Succeeded by Joseph Arthur Ankrah |

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| Name | Nkrumah, Kwame |

| Alternative names | Ngonloma, Francis Nwia Kofi |

| Short description | Pan Africanist and First Prime Minister and President of Ghana |

| Date of birth | September 21, 1909(1909-09-21) |

| Place of birth | Nkroful, Western Region, Ghana |

| Date of death | 27 April 1972(1972-04-27) |

| Place of death | Bucharest, Romania |