Kamal's Final Moments (original) (raw)

by June HL Wong and Ong Ju Lin

WHEN the Indonesian soldiers started pumping bullets into the East Timorese protesters at the Santa Cruz cemetery in Dili on Nov 12, 1991, Malaysian activist Kamal Bamadhaj was near the front of the crowd.

WHEN the Indonesian soldiers started pumping bullets into the East Timorese protesters at the Santa Cruz cemetery in Dili on Nov 12, 1991, Malaysian activist Kamal Bamadhaj was near the front of the crowd.

He somehow survived the murderous hail, apparently sustaining only an arm injury, acording to a medical report his mother, Helen Todd received later. Eye-witnesses saw him walking away alone from the scene of carnage, barefoot.

In the documentary, Punitive Damage, Jose Verdial, a Timorese who took part in the demonstration, said he saw Kamal walking towards him, outside the cemetery, when a military truck that was following him pulled up next to him. An argument ensued, apparently over the camera Kamal was holding.

Seconds later, Kamal was shot in his chest by a military intelligence officer who had come out of the truck. He was left lying on the roadside. Kamal did not die immediately and had managed to flag down a passing Red Cross ambulance.

"When he was helped by the Red Cross, he was still talking,'' recounted Verdial. "Every time he spoke, blood gushed out from his wound.''

Further investigations by Todd revealed that Kamal died of blood loss as a result of delays in getting him to the hospital. The Red Cross ambulance was stopped twice by military and police road blocks.

At the second block, the police forced the ambulance driver into a police station compound and demanded he dump Kamal there. The courageous driver refused. He was finally allowed to send Kamal, who was bleeding profusely, to hospital. By that time, it was too late. He died 20 minutes later.

In_Punitive Damage_, American journalist Allan Nairn, who knew Kamal, recalled how tense and explosive the situation was in Dili, following the killing of a Timorese youth, Sebastiao Gomes, in a church by Indonesian soldiers on Oct 28 and the cancellation of the United Nations sponsored visit by a delegation of Portuguese parliamentarians on Nov 3.

In_Punitive Damage_, American journalist Allan Nairn, who knew Kamal, recalled how tense and explosive the situation was in Dili, following the killing of a Timorese youth, Sebastiao Gomes, in a church by Indonesian soldiers on Oct 28 and the cancellation of the United Nations sponsored visit by a delegation of Portuguese parliamentarians on Nov 3.

Nairn said that when the soldiers attacked the Motael Church, it stunned the people because their "final sanctuary had been violated."

When word got out that the delegation's visit had been called off, the Timorese were in total despair. They had pinned tremendous hopes on the visit. At last, after 16 years of brutal oppression and isolation, the world would finally learn of their plight.

Many of the Timorese, defying the authorities' warnings of reprisal if they spoke to the Portuguese, had been preparing to gain the delegation's attention with banners and petitions. With the beacon of hope extinguished, they feared they would be singled out and killed.

Kamal, who knew many of the young Timorese, felt their fear and despair. He called his Australian girlfriend, Bibi Langker, in Sydney begging her to do something.

"He was desperate for the Portuguese to come. He asked me to go to the embassy to get them to come. He was really, really upset," she said in Punitive Damage.

When the Timorese decided to organise a memorial march for Gomes, Kamal begged the Western journalists (who were staying in the same hotel with him in Dili) to be present in the hope it would prevent violence by the Indonesian troops.

"Kamal himself was actually quite nervous about going. Then he decided to go and he got himself a camera," said Nairn.

Helen Todd marvels that "this boy who could never get up in the morning" set his alarm clock for 5.30am and woke everyone else.

The march started from the church near the beach and moved on to the cemetery. As they went along, the protestors pulled out banners calling for freedom.

As they gathered in the cemetery, Indonesian soldiers arrived and started shooting. "I couldn't believe it. At first I thought they were firing blanks. Then I saw people crumpling. They were being shot in the back as they tried to escape," recounted Nairn.

He said when the shooting stopped, the soldiers moved in and beat and stabbed the hapless Timorese still trapped in the cemetery.

Nairn, who sustained a cracked skull, said he survived because he shouted to the soldiers that he was American. He guessed, apparently correctly, that the Indonesians wouldn't kill a citizen of a nation which was supplying them with the guns and bullets.

A total of 271 people died that day, including Kamal, Malaysia's only casualty in the East Timorese cause.

Todd was prevented by the Indonesian authorities from going to Dili to bring his body back.

She was kept in Jakarta where a coffin arrived three days later. She was unable to identify the body because she was told Kamal had been buried immediately and then exhumed, rendering him unrecognisable.

Kamal's sister, Nadiah, says that when her uncle helped to bury the body in the grave in Bukit Kiara, Kuala Lumpur, he remarked that the body seemed too tall.

"Who knows, maybe it's a Timorese in Kamal's place," she speculates.

Her father, Ahmed Bamadhaj, however, believes it's his son's body, saying he had recognised Kamal's hair. The alternative, that it's not Kamal's body, is too terrible for him to contemplate.

Ahmed remembers a conversation he had with Kamal the last time he saw his son.

"He said to me: 'You know, Aba, there are some things in this world that are worth fighting for. And if it is going to cost me my life, I am prepared to give it.'

"I knew then that I could not stop him from doing what he believed in. I could only tell him to be careful."

But many, including East Timorese leader Jose Ramos Horta, who had used Kamal as a courier, and his mother, believe Kamal was marked for death by the army intelligence.

Says Todd, "He was deliberately targeted and murdered."

In Punitive Damage, Timorese activist Abel Guterras paid Kamal a moving tribute:

"He was a friend; a foreigner who came and showed his solidarity with us. It was sad that he came to our land and died for our freedom."

-----

The Boy Who Loved People

by Ong Ju Lin

NINE years after Kamal Bamadhaj's death, as East Timor prepares for its independence from Indonesia, the young man is barely remembered by most Malaysians. But for his father, businessman Ahmed Bamadhaj, it is as if his son had died the day before.

"I still have nightmares occasionally about how he was killed. I still see him. I go around the streets of KL and sometimes see someone who looks like Kamal from the back ... and hope against hope that it is him,'' says Ahmed, his voice thick with emotion.

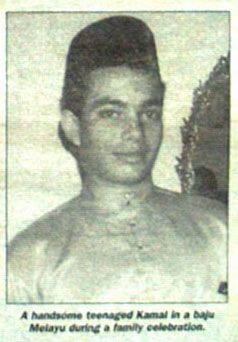

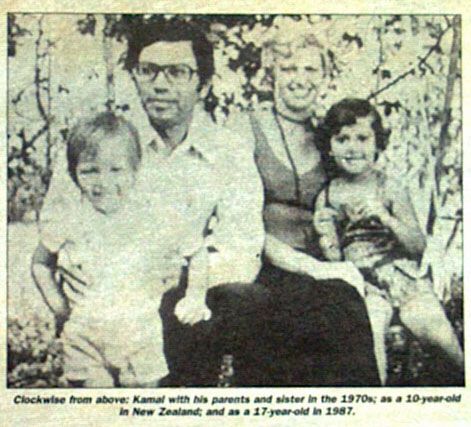

Kamal as born on Dec 23, 1970, the second child of Ahmed and his first wife, Helen Todd. They have two daughters, Nadiah, 31, and Haanim, 22.

Ahmed, who had never spoken openly about his son's death, remembers Kamal as an extraordinary child. As a young boy, he had shown a glimpse of the man he was to be.

"Kamal was a curious child and was always enthusiastic about learning new things. He was popular with everyone. He moved around without barriers or any hang-ups. And he was thoughtful and compassionate towards the less privileged,'' says his father at his home in Kuala Lumpur.

Ahmed recalls an incident during Hari Raya when Kamal was eight. "We had done our Hari Raya shopping and Kamal approached me and very gently asked, "Can you buy a pair of shoes for my friend?' I asked him why and he replied that his friend was poor and that he needed new shoes to replace his tattered ones. That was Kamal.

With his university friends, Kamal was known as the "peacemaker''.

"In debates, he was always calming everyone down, resolving conflicts and finding the middle way,'' says Elisabeth Wong who now works with the human rights organisation, Suaram.

Rather than being sucked into the arguments about capitalism or socialism as the end to poverty and social ills, Kamal believed that there were many other unexplored alternatives.

In a diary entry entitled, Dreams of a Thousand Roads, Kamal wrote: "While we were busy becoming more entrenched in the 'to be a socialist or to be a capitalist' debate, the fundamental aims of our loving humanitarian idealism (promoting social justice, creating egalitarianism, helping those with nothing no food, no shelter, no self-esteem) was fading away.''

Kamal's ideas on justice reflected his personality. He was described by his friends as someone who was liked by people because he was warm, personal and generous to everyone he met.

"Kamal was a compassionate young man. He had a big heart and a tremendous conviction toward humanitarianism,'' says Wong. The first time Wong met Kamal, he had bounded up to her to ask her if she was interested in joining a peace protest against Indonesia.

"He was barefoot. When I asked him why he went around kaki ayam, he replied that one must feel close to Mother Earth. He was also a devout vegetarian,'' Wong says.

Kamal's affinity to the plight of the East Timorese was no surprise to those who knew him. He grew up in a family where political awareness and social activism were discussed openly. Kamal's mother, Helen Todd, was a great influence.

A New Zealander, she married Ahmed Bamadhaj in 1968. In 1977 she gained her Malaysian citizenship and joined the New Straits Times as a journalist, writing under the byline Halinah Todd. She resigned from the paper in 1985.

Nadiah recalls that she and Kamal were exposed to many socio-political issues by their mother, including abuses by institutions of power. In Aksi Write (Rhino Press, 1997), a book by Nadiah on Kamal and his diaries, she wrote of Kamal's early influences.

Once such account was when Kamal was 11. Todd had taken him to Tasik Bera in Pahang to write on how the Felda land schemes were drying up the lake which the Semelai tribe depended on. Nadiah remembers Todd and Kamal staying up all night while the tribal elders nursed a sick child.

Once such account was when Kamal was 11. Todd had taken him to Tasik Bera in Pahang to write on how the Felda land schemes were drying up the lake which the Semelai tribe depended on. Nadiah remembers Todd and Kamal staying up all night while the tribal elders nursed a sick child.

Todd was, and still is, involved in Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia (AIM), a project to eradicate poverty among the hard-core poor.

During his teens, Kamal worked in Sabak Bernam, Selangor, hauling bags of poultry feed for the farmers who were involved in the project. Later, using the same AIM concepts, he tried to implement the project in East Timor in 1990. Todd, who was divorced from Ahmed when Kamal was still a boy, will accomplish her son's dream by implementing a similar project in East Timor later this year.

Kamal first became interested in East Timor in 1989, as a result of his involvement in student activism at the University of New South Wales, Australia. He became part of the Network of Overseas Student Collectives (Nosca), a highly politicised student group consisting of mainly Malaysians, campaigning on domestic and international issues.

Despite giving so much of his time to his activism work, writing (he was extremely prolific, judging from his letters, diary entries and poems) and weekend jobs to support himself, Kamal was a brilliant and conscientious student, consistently scoring A's, says Ahmed.

In 1990, Kamal visited East Timor for the first time and witnessed for himself the situation which he had only read and heard about. This visit was crucial in making Kamal return to the troubled territory a year later.

Nadiah remembers that the last time she saw Kamal was a year before he was killed, just after his travels. "I remember that he was really troubled. He had just come back from East Timor and had witnessed the extent of the suffering there. He came back to Kuala Lumpur and was shocked that people were completely clueless about East Timor.''

Nadiah remembers that the last time she saw Kamal was a year before he was killed, just after his travels. "I remember that he was really troubled. He had just come back from East Timor and had witnessed the extent of the suffering there. He came back to Kuala Lumpur and was shocked that people were completely clueless about East Timor.''

A passage that Kamal wrote in a letter to his parents at the end of 1990 sheds some light on his concern and frustration:

"The Timorese are surrounded by fear. Fear like I've never felt before. There are intelligence and military people everywhere and hence it is difficult to get into conversation with people who are frightened or suspicious or both!

"I met victims of torture and people who had lost most of their families in the massacre of the 1970s when Indonesia invaded East Timor ... the most glaring thing was the huge military presence and the atmosphere of fear.

"People are still being taken away by the military at night and killed. (They) ... seem to have no one to appeal to ... no protection. It is frustrating and scary.''

From then on, all his activities were focused on his political beliefs aimed at social change. He took up the Asian studies programme, giving up law studies for he had begun to believe that little change could come out of the human rights situation in South-East Asia through legal channels.

With Tian Chua, Kamal founded Aksi, an off-shoot of Nosca, to raise awareness on human rights issues in Indonesia. Chua, a human rights activist and Keadilan vice-president, remembers Kamal as an enthusiastic, energetic young man whose passion for justice was infectious.

In commemorating the death of Kamal in a public forum welcoming East Timor leaders Xanana Gusmao and Jose Ramos Horta in February, Chua said: "There comes a time when one has to make a decision whether to stand on the sidelines or stand in solidarity with one's fellow man.''

Undoubtedly, Kamal chose the latter, and paid the price with his life.

Published in The Star Malaysia, (www.thestar.com.my) May 5, 2000