Morgan le Fay (original) (raw)

Siân Echard, University of British Columbia

The image from Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS français 102, folio 239v, appears in accordance with the BNF terms of non-commercial use.

Morgan-le-Fay, by Frederick Sandys, 1863-1864. Image appears in accordance with the Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery terms for educational use.

Frederick Sandys (1829-1904) shows, in his 1864 painting Morgan-le-Fay, a common view of Morgan as the dangerous yet seductive enchantress. In this painting, she is creating a magical cloak which is intended to burn its wearer to cinders, with the intention of sending it to Arthur: Malory tells this story in Book IV, chapter 16. The books, the lamp, the cabbalistic signs on the cloak are all intended to evoke the association of Morgan with magic, but as this page will show you, she has not always been understood as a wicked magician.

To read more about the appearance of Arthurian figures in art, look for Muriel Whitaken, The Legends of King Arthur in Art (Cambridge, 1990); Christine Poulson, The quest for the Grail: Arthurian legend in British Art 1840-1920 (Manchester, 1999); and Debra N. Mancoff, The Return of King Arthur: The Legend through Victorian Eyes (New York, 1995).

The Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery has an extensive page on this painting here; you should also have a look at their Pre-Raphaelite Online Resource.

Morgan first appears in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Vita Merlini, lines 916-39:

That is the place where nine sisters administer genial rule over those who come to them from our homelands, and the first of them is the more learned in the art of healing, and her beauty exceeds that of her sisters. Her name is Morgan and she had learned what the use is of every kind of plant in curing the weaknesses of the body. She also knows the art of changing her appearance and of flying, like Daedalus, through the air on curious wings. As she wills it, she can be at Brest or at Chartres or at Pavia; and as she wills, she comes from the skies to your shores. They say she taught mathematica to her sisters Monrone, Mazoe, Gliten, Glitonea, Gliton, Tyronoe, Thiten– Thiten is famous for her lyre. It was there that we took Arthur after the battle of Camlann where he was wounded– Barinthus guided us because he knew about the seas and the stars of the heavens. With him at the helm we came there with the prince, and Morgan received us with honour, as was fitting, and placed the king in her chamber on a golden bed, and with her hand she unwrapped his wound and looked at it for a while, and then said that it would be possible to return him to health if he were to stay with her for a long time and place himself in her hands. Rejoicing, therefore, we committed the king to her...

Morgan has been connected to various Celtic deities: the Morrigan are Irish battle deities; Modron is a divine mother; Macha is an Irish goddess of war, life, and death. Basil Clarke, in his edition of the Vita Merlini, suggests that Geoffrey is modelling his Morgan at least in part on figures such as Circe in the Odysseus story.

Gerald of Wales also makes Morgan a queen and healer, in his description of Avalon/ Glastonbury in the De instructione principum:

It was here, to this island which is now called Glastonbury, that Morgan, a noble matron and the ruler and patron [dominatrix atque patrona] of those parts, and also close in blood to King Arthur, took Arthur after the battle of Camlann for the healing of his wounds....

The images above all show Morgan in her role as queen of Avalon and one of those who receives Arthur’s body. The top is James Archer (1823-1904), The Death of Arthur . Directly above on the left is the final illustration in Mary Macgregor’s Stories of King Arthur's Knights, in the Told to the Children series. The illustrator is Katharine Cameron. On the right is one of Daniel Maclise’s 1857 illustrations to Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Idylls of the King . These images are all in the public domain.

Morgan comes to have several major, somewhat contradictory, roles in the Arthurian legend, though the association with magic is constant. As in Sandys’s painting, she can be her brother Arthur’s sworn enemy, determined to destroy him. Sometimes she is the enemy, not of Arthur, but rather of Guenevere, and in this role she often tries to expose the affair between Lancelot and Guenevere, as for example when she gives Tristan a shield that depicts the relationship, in the hopes of making it public, a story Malory tells in IX.40. This incident is illustrated by the manuscript illumination at the top of this page, and by the image below:

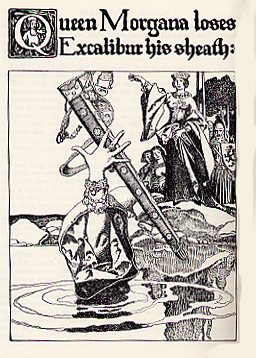

One of the most famous 19th-century printings of a medieval text was J.M. Dent’s Birth Life and Acts of King Arthur (London, 1893 - 1894), an edition of Malory’s Le Morte Darthur based on Caxton’s 1485 printing. Dent, later to become famous as the publisher of the Everyman’s Library series, was at the time a fairly obscure London publisher, albeit one with an interest in fine printing. While William Morris’s Kelmscott Press books were produced on traditional hand presses, Dent seems to have been interested in demonstrating that a fine book could be produced using modern machinery. He chose as his illustrator Aubrey Beardsley (1872 - 1898), a young clerk whom he met through the bookseller and photographer F.H. Evans. He paid Beardsley £250 for a series of illustrations to Malory’s Morte. Beardsley produced over 350 designs, including letters, ornaments, and full-page illustrations. The text was issued in 12 parts between June 1893 and mid-1894. There were two forms: a Large Paper edition on Dutch handmade paper, printed in black and red and limited to 300 copies; and a Small Paper edition on smooth gray-green paper, printed in black only, and limited to 1500 copies. The Large Paper run cost 6s 6d per part, while the Small Paper was exactly one-third the cost. Beardsley also designed the paper wrappers for both runs and for the binding cases which the publisher offered to subscribers at an additional cost: the Small Paper edition was also sold ready-bound at 2 guineas. The book’s subsequent fame makes it hard to believe that it was little noticed at first, but the fact that it was sold by subscription limited its visibility to reviewers. The first print run of the Small Paper edition did not sell out immediately, but the Large Paper edition was fully subscribed at once, and few copies of it are in circulation today.

The above text is taken from my notes to a 1999 exhibition of rare books from UBC’s Special Collections. The Colbeck Collection, part of Rare Books and Special Collections, includes copies of the Beardsley/ Dent Malory in both the deluxe and ordinary printings, and it also also includes copies the second Dent edition of 1909, a single volume issued in 1500 copies, and the third Dent edition of 1927, issued in 1600 copies and including designs inadvertently omitted from the first edition. You can visit an online version of the display by clicking here. The image is in the public domain.

The sensuality of the Sandys and Beardsley images above also connect to another common treatment of Morgan, one which emphasizes her lust. She is, for example, one of the four queens who try to enchant Lancelot and force him to choose one of them as lover, a story Malory retells in VI.3:

Image copyright © 2012 Peter Nahum, in accordance with the Peter Nahum Terms and Conditions of Use.

The painting above is by Frank Cadogan Cowper (1877-1958). It is called The Four Queens Find Lancelot Sleeping (1854). There is a gallery for Cowper at ArtMagick.

The pictures above of Morgan are taken from Howard Pyle’s The story of King Arthur and his knights (New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1903).

Howard Pyle (1853 - 1911) wrote and illustrated four Arthurian books, of which this is the first (he is also well known for another medieval subject, his Robin Hood). Pyle was the most important American illustrator of his generation, and teacher to a host of others, including N. C. Wyeth. The overall design and illustration of the books suggest something of Beardsley, but with a robust muscularity which is altogether his own.

Pyle was born and raised in Wilmington, Delaware, and had his own schools at Chadd’s Ford, Pennsylvania, and at Wilmington; the influence of rural life is evident in his medieval illustrations. His women are often enigmatic features: compare the treatment of Morgan to that of Guenevere and the Lady of the Lake, below.

Some of the above text is taken from my notes to a 1999 exhibition of rare books from UBC’s Special Collections. The Arkley Collection of Historical Children’s Literature was a major source for books displayed at that time.

Perhaps the most famous modern reinterpretation of Morgan is found in Marion Zimmer Bradley’s 1982 The Mists of Avalon. This fantasy novel tells the story from the point of view of the women. Morgaine, here Arthur’s sister and the mother of Arthur’s son Gywdion (the Mordred figure) represents the story as a conflict between the old religions (earth religions represented by the druids and the worshippers of the mother goddess) and Christianity. The novel begins in Morgaine’s voice:

MORGAINE SPEAKS...

In my time I have been called many things: sister, lover, priestess, wise-woman, queen. Now in truth I have come to be wise-woman, and a time may come when these things may need to be known. But in sober truth, I think it is the Christians who will tell the last tale. For ever the world of Fairy drifts further from the world in which the Christ holds sway. I have no quarrel with the Christ, only with his priests, who call the Great Goddess a demon and deny that she ever held power in this world. At best, they say that her power was of Satan. Or else they clothe her in the blue robe of the Lady of Nazareth – who indeed had power in her way, too – and say that she was ever virgin. But what can a virgin know of the sorrows and travail of mankind?

And now, when the world has changed, and Arthur – my brother, my lover, king who was and king who shall be – lies dead (the common folk say sleeping) in the Holy Isle of Avalon, the tale should be told as it was before the priests of the White Christ came to cover it all with their saints and legends.

©Siân Echard. Not to be copied, used, or revised without explicit written permission from the copyright owner.