Edith New (original) (raw)

Sections

Edith New, one of five children of Isabella Frampton New, a music teacher, and Frederick James New, a railway clerk was born in Swindon on 17th March 1877. Her father was killed by a train in 1878. (1)

In 1891, aged 14, she began working as a teacher. New was a supporter of women's suffrage and in 1906 she joined the Women's Social and Political Union. Established by Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Sylvia Pankhurst and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, it had become frustrated by the lack of success by the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). (2)

New was one of those who believed that the WSPU should adopt more militant tactics. In January 1908 Edith New chained herself to the railings of 10 Downing Street. According to The Daily Express: "Each suffragist wore round her waist a long, steel chain - not unlike a very heavy dog chain. Each took the loosened end of the chain, threw it round the railings, and fixed it to the rest of the chain. This was done so deftly that it was not until the police heard the click of the lock that they understood the clever move by which the suffragists had outwitted them, and prevented for a time their own removal. Votes for women! shouted the two voluntary prisoners simultaneously. Votes for Women!" (3)

Illustration of Edith New being arrested in January 1908.

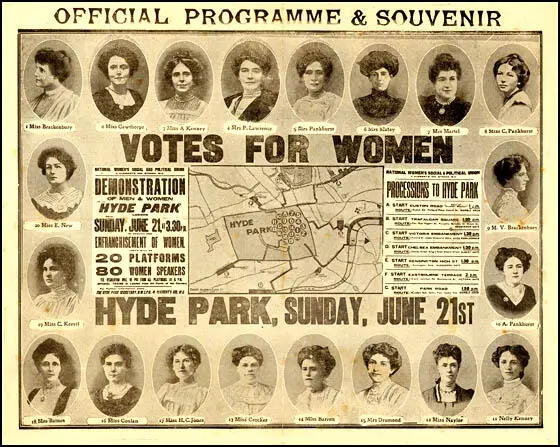

The WSPU organised a mass meeting to take place on 21 June 1908 called Women's Sunday at Hyde Park. The leadership intended it "would out-rival any of the great franchise demonstrations held by the men" in the 19th century. Sunday was chosen so that as many working women as possible could attend. It is claimed that it attracted a crowd of over 300,000. At the time, it was the largest protest to ever have taken place in Britain. Speakers included Edith New, Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Adela Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Mary Gawthorpe, Jennie Baines, Rachel Barrett, Marie Brackenbury, Georgina Brackenbury, Annie Kenney, Nellie Martel, Marie Naylor, Flora Drummond and Gladice Keevil. (4a)

Women's Sunday at Hyde Park Official Programme & Souvenir

On 30th June, 1908, Edith New attended a public meeting in Parliament Square. The authorities decided to send in 5,000 foot police and 50 mounted men to break-up the meeting. Sylvia Pankhurst later reported: "Women spoke from the steps of the Government buildings and offices in Broad Sanctuary, they lifted themselves above the people by the railings round the Abbey Gardens and Palace Yard, or raised their voices standing among the crowds on road or pavement. They were torn by the harrying constables from their foothold and flung into the masses of people... Then roughs appeared, organized gangs, who treated the women with every type of indignity... I was obliged to drop my handbag with keys and purse, to have my hands free to protect myself. The roughs were constantly attempting to drag women down side streets away from the main body of the crowd... Enraged by the violence and indecency in the Square, Mary Leigh and Edith New took a cab into Downing Street, and flung two small stones through the windows of the Prime Minister's house." (4) It was later revealed that these gangs had been hired by Scotland Yard. (5)

The next day at Westminster police court twenty-seven women were sent to prison for terms varying from one to two months. Edith New and Mary Leigh, were sentenced to two months in Holloway Prison. In court the women wore white dresses and were relieved to hear the sentence because they feared it would be a much longer sentence. However, the Manchester Guardian protested in a leading article: "Their stringent imprisonment... violates the public conscience." (6) However, Millicent Fawcett, leader of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), said later that it was this incident that resulted in her condemning the methods being used by the WSPU. (7)

Mary Leigh (left) and Edith New (right) leaving Holloway Prison (23rd August 1908)

Edith New and Mary Leigh were released from prison on 23rd August. They were welcomed on release by a team of women in white dresses who drew their carriage from Holloway to Clements Inn. They were greeted by a brass band and accorded a ceremonial welcome breakfast attended by the two main leaders of the WSPU, Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. (8)

The carriage of Mary Leigh (left) and Edith New (right) being pulled

from Holloway to Queen's Hall on 23rd August 1908.

On 25th June 1909, Marion Wallace-Dunlop was found guilty of wilful damage and when she refused to pay a fine she was sent to prison for a month. On 5th July, 1909 she petitioned the governor of Holloway Prison: “I claim the right recognized by all civilized nations that a person imprisoned for a political offence should have first-division treatment; and as a matter of principle, not only for my own sake but for the sake of others who may come after me, I am now refusing all food until this matter is settled to my satisfaction.” (9)

Wallace-Dunlop refused to eat for several days. Afraid that she might die and become a martyr, it was decided to release her. According to Joseph Lennon: "She came to her prison cell as a militant suffragette, but also as a talented artist intent on challenging contemporary images of women. After she had fasted for ninety-one hours in London’s Holloway Prison, the Home Office ordered her unconditional release on July 8, 1909, as her health, already weak, began to fail". (10)

On 22nd September 1909 Charlotte Marsh, Laura Ainsworth and Mary Leigh were arrested while disrupting a public meeting being held by Herbert Asquith. Marsh, Ainsworth and Leigh were all sentenced to two weeks' imprisonment. They immediately decided to go on hunger-strike, a strategy developed by Marion Wallace-Dunlop a few weeks earlier. Wallace-Dunlop had been immediately released when she had tried this in Holloway Prison, but the governor of Winson Green Prison, was willing to feed the three women by force. (11)

The authorities believed that force-feeding would act as a deterrent as well as a punishment. This was a serious miscalculation and in many ways it had the opposite effect. Militant members of the WSPU now had beliefs as strong as any religion and now they could argue that women were actually being tortured for their faith. "Suffragettes submitted to force-feeding as a way to express solidarity with their friends as well as to further the cause." Edith New also adopted this approach and endured several hunger-strikes. (12)

At a meeting in France, Christabel Pankhurst told Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence about the proposed arson campaign. When they objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us." (13) Edith New also disagreed with this new policy and she left the WSPU and moved to Lewisham to resume her teaching career. (14)

Edith New died on 2nd January 1951.

Primary Sources

(1) The Daily Express (18th January, 1908)

The militant women suffragists made another raid on No. 10 Downing-street, the official residence of the prime minister. Two of their number, Mrs Drummond and Miss Mary Garth, succeeded in reaching the swing-doors leading into the historic council chamber. While these women were being ejected two others - Miss New and Nurse Chew - chained and padlocked themselves to the railings outside the premier's residence. It was some time before police inspectors could break the chains and escort the released suffragists to Cannon-row Police Station.

Each suffragist wore round her waist a long, steel chain - not unlike a very heavy dog chain. Each took the loosened end of the chain, threw it round the railings, and fixed it to the rest of the chain. This was done so deftly that it was not until the police heard the click of the lock that they understood the clever move by which the suffragists had outwitted them, and prevented for a time their own removal. 'Votes for women!' shouted the two voluntary prisoners simultaneously. 'Votes for Women?'

(2) Sylvia Pankhurst, The Suffrage Movement (1931)

Mary Leigh and her colleagues, who were organising there, began by copying the police methods so far as to address a warning to the public not to attend Mr. Asquith's meeting, as disturbances were likely to ensue, and immediately the authorities were seized with panic. A great tarpaulin was stretched across the glass roof of the Bingley Hall, a tall fire escape was placed on each side of the building, and hundreds of yards of firemen's hoses were laid across the roof. Wooden barriers, nine feet high, were erected along the station platform and across all the leading thoroughfares in the neighbourhood, whilst the ends of the streets both in front and at the back of Bingley Hall were sealed up by barricades. Nevertheless, inside those very sealed-up streets, numbers of Suffragettes had been lodging for days past and were quietly watching the arrangements.

When Mr. Asquith left the House of Commons for his special train, detectives and policemen hemmed him in on every side, and when he arrived at the station in Birmingham, he was smuggled to the Queen's Hotel by a back subway a quarter of a mile in length and carried up in a luggage lift.

Meanwhile, tremendous crowds were thronging the streets and the ticket holders were watched as closely as spies in time of war. They had to pass four barriers and were squeezed through them by a tiny gangway and then passed between long lines of police and amid an incessant roar of "show your ticket." The vast throngs of people who had no tickets and had only come out to see the show surged against the barriers like great human waves, and occasionally cries of "Votes for Women" were greeted with deafening cheers.

Inside the hall there were armies of stewards and groups of police at every turn. The meeting began by the singing of a song of freedom led by a band of trumpeters. Then the Prime Minister appeared. "For years past the people have been beguiled with unfulfilled promises," he declared, but during his speech he was again and again reminded, by men, of the unfulfilled promises which had been made to women; and, though men who interrupted him on other subjects were never interfered with, these champions of the Suffragettes were, in every case, set upon with a violence which was described by onlookers as "revengeful" and "vicious." Thirteen men were maltreated in this way.

Meanwhile, amid the vast crowds outside women were fighting for their freedom. Cabinet Ministers had sneered at them and taunted them with not being able to use physical force. "Working men have flung open the franchise door at which the ladies are scratching," Mr. John Burns had said. So now they were showing that, if they would, they could use violence, though they were determined that, at any rate as yet, they would hurt no one. Again and again they charged the barricades, one woman with a hatchet in her hand, and the friendly people always pressed forward with them. In spite of a thousand police the first barrier was many times thrown down. Whenever a woman was arrested the crowd struggled to secure her release, and over and over again they were successful, one woman being snatched from the constables no fewer than seven times.

Inside the hall Mr. Asquith had not only the men to contend with, for the meeting had not long been in progress when there was a sudden sound of splintering glass and a woman's voice was heard loudly denouncing the Government. A missile had been thrown through one of the ventilators by a number of Suffragettes from an open window in a house opposite. The police rushed to the house door, burst it open, and scrambled up the stairs, falling over each other in their haste to reach the women, and then dragged them down and flung them into the street, where they were immediately placed under arrest. Even whilst this was happening there burst upon the air the sound of an electric motor horn which issued from another house near by. Evidently there were Suffragettes there too. The front door of this house was barricaded and so also was the door of the room in which the women were, but the infuriated Liberal stewards forced their way through and wrested the instrument from the woman's hands.

No sooner was this effected, however, than the rattling of missiles was heard on the other side of the hall, and on the roof of the house, thirty feet above the street, lit up by a tall electric standard was seen the little agile figure of Mary Leigh, with a tall fair girl beside her (Charlotte Marsh). Both of them were tearing up the slates with axes, and flinging them onto the roof of the Bingley Hall and down into the road below-always, however, taking care to hit no one and sounding a warning before throwing. The police cried to them to stop and angry stewards came rushing out of the hall to second this demand, but the women calmly went on with their work. A ladder was produced and the men prepared to mount it, but the only reply was a warning to "he careful" and all present felt that discretion was the better part of valour. Then the fire hose was dragged forward, but the firemen refused to turn it on, and so the police themselves played it on the women until they were drenched to the skin. The slates had now become terribly slippery, and the women were in great danger of sliding from the steep roof, but they had already taken off their shoes and so contrived to retain a foothold, and without intermission they continued "firing" slates. Finding that water had no power to subdue them, their opponents retaliated by throwing bricks and stones up at the two women, but, instead of trying, as they had done, to avoid hitting, the men took good aim at them and soon blood was running, down the face of the tall girl, Charlotte Marsh, and both had been struck several times.

At last Mr. Asquith had said his say and came hurrying out of the building. A slate was hurled at the back of his car as it drove away, and then "firing" ceased from the roof, for the Cabinet Minister was gone. Seeing that they now had nothing to fear the police at once placed a ladder against the house and scrambled up to bring the Suffragettes down, and then, without allowing them to put on their shoes, they marched them through the streets, in their stockinged feet, the blood streaming from their wounds and their wet garments clinging to their limbs. At the police station bail was refused and the two women were sent to the cells to pass the night in their drenched clothing.

We knew that Mary Leigh, Charlotte Marsh, and their comrades in the Birmingham prison would carry out the hunger-strike, and, on the following Friday, September 24, reports appeared in the Press that the Government had resorted to the horrible expedient of feeding them by force by means of a tube passed into the stomach. Filled with concern, the committee of the Women's Social and Political Union at once applied both to the prison and to the Home Office to know if this were true but all information was refused.

(3) Frances Bevan, The Swindon Advertiser (7th October, 2009)

Between 1905 and 1914 more than 1,000 women had been imprisoned during the votes for women campaign, among them Swindon-born militant suffragette, Edith New.

Despite demands for suffragettes to be treated as political prisoners detained in the first division - a separate category of "non-criminal" prisoners given special treatment - they invariably served their sentences in the criminal second and third divisions and received harsh treatment.

Many went on hunger and thirst strike and were subjected to the barbaric forcible feeding regime. Restrained by prison staff, a doctor would insert a tube through the mouth or nose into the stomach, down which a "nourishing" liquid was poured.

With the introduction of the Prisoners' Temporary Discharge For Ill Health Act in 1913, commonly called the "Cat and Mouse"Act, suffragettes weakened by hunger strike and forcible feeding were released from prison until their health improved, when they were subsequently re-arrested.

Edith was born in North Street, Swindon, the daughter of railway clerk Frederick New and his wife Isabella.

She worked first as a teacher at Queenstown Infant's School before moving to London. By 1908 she was employed as a staff organiser for the Women's Social and Political Union, travelling the country to attend by elections and demonstrations nationwide.

Edith quickly became associated with the militant wing of the suffrage movement and served several terms of imprisonment. She is probably best known for breaking windows at 10 Downing Street with Mary Leigh in July 1908. Both women were sentenced to two months' hard labour in Holloway Prison.

"My dear Edith," her anxious mother Isabella wrote from 29 Lethbridge Road in a letter dated July 25, 1908, more than three weeks after Edith was sentenced following the Downing Street protest. "I am writing this without much hope of its reaching you yet awhile .......The dead silence is hard to bear and not to know how you are, and how being treated."

"Don't on any account worry about me, because I am uncommonly well," Edith replied in an attempt to reassure her mother. "We are not allowed to make any mention of prison life or discipline so that must wait till I see you or write later."

In 1926 Edith How Martyn, a former activist, founded the Suffragette Club. It was later renamed the Suffragette Fellowship, and aimed "to perpetuate the memory of the pioneers and outstanding events connected with women's emancipation and especially with the militant suffrage campaign, 1905-14, and thus keep alive the suffragette spirit."

The Suffragette Fellowship established three annual commemorative days which became known as Days of Obligation: Women's Suffrage Day on February 6, Emmeline Pankhurst's birthday on July 14 and Prisoner's Day October 13, the date of the first militant protest and imprisonment.

Alongside the more famous names of the Pankhurst women on the Suffragette Prisoner's Roll of Honour stands Edith New, a Swindon schoolteacher.