Armistice (original) (raw)

Sections

The German government of Max von Baden asked President Woodrow Wilson for a ceasefire on 4th October, 1918. "It was made clear by both the Germans and Austrians that this was not a surrender, not even an offer of armistice terms, but an attempt to end the war without any preconditions that might be harmful to Germany or Austria." This was rejected and the fighting continued. On 6th October, it was announced that Karl Liebknecht, who was still in prison, demanded an end to the monarchy and the setting up of Soviets in Germany. (1)

Although defeat looked certain, Admiral Franz von Hipper and Admiral Reinhard Scheer began plans to dispatch the Imperial Fleet for a last battle against the Royal Navy in the southern North Sea. The two admirals sought to lead this military action on their own initiative, without authorization. They hoped to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy, to achieve a better bargaining position for Germany regardless of the cost to the navy. Hipper wrote "As to a battle for the honor of the fleet in this war, even if it were a death battle, it would be the foundation for a new German fleet...such a fleet would be out of the question in the event of a dishonorable peace." (2)

The naval order of 24th October 1918, and the preparations to sail triggered a mutiny among the affected sailors. By the evening of 4th November, Kiel was firmly in the hands of about 40,000 rebellious sailors, soldiers and workers. "News of the events in Keil soon travelled to other nearby ports. In the next 48 hours there were demonstrations and general strikes in Cuxhaven and Wilhelmshaven. Workers' and sailors' councils were elected and held effective power." (3)

By the 8th November, workers councils took power in virtually every major town and city in Germany. This included Bremen, Cologne, Munich, Rostock, Leipzig, Dresden, Frankfurt, Stuttgart and Nuremberg. Theodor Wolff, writing in the Berliner Tageblatt: "News is coming in from all over the country of the progress of the revolution. All the people who made such a show of their loyalty to the Kaiser are lying low. Not one is moving a finger in defence of the monarchy. Everywhere soldiers are quitting the barracks." (4)

The German Social Democratic Party (SDP) in the Reichstag demanded the resignation of Kaiser Wilhem II. When that was refused, they resigned from the Reichstag and called for a general strike throughout Germany. In Munich, Kurt Eisner, the leader of the Independent Socialist Party, declared the establishment of the Bavarian Soviet Republic.

Konrad Heiden wrote: "On November 6, 1918, he (Kurt Eisner) was virtually unknown, with no more than a few hundred supporters, more a literary than a political figure. He was a small man with a wild grey beard, a pince-nez, and an immense black hat. On November 7 he marched through the city of Munich with his few hundred men, occupied parliament and proclaimed the republic. As though by enchantment, the King, the princes, the generals, and Ministers scattered to all the winds." (5)

Later that day, in order to stop the spread of the revolution, the German government agreed to surrender. On 9th November, the Kaiser abdicated fled to Holland. At 5 a.m. on 11th November, 1918, signed the armistice. It came into force at 11 a.m. All territorial conquests achieved by the Central Powers had to be abandoned. The German Army also surrendered 30,000 machine-guns, 2,000 aircraft, 5,000 locomotives, 5,000 lorries and all its submarines. (6)

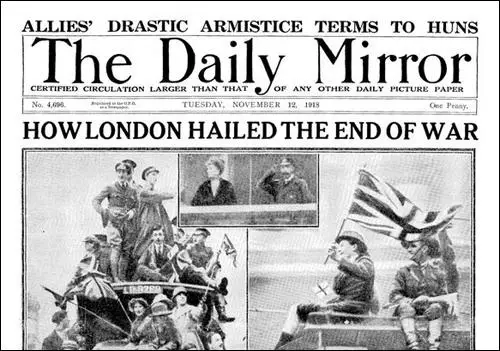

The Daily Mirror (12th November, 1918)

The journalist, Philip Gibbs, described how the men responded on the front-line at Mons. "They wore flowers in their caps and in their tunics, red and white chrysanthemums given them by the crowds of people who cheered them on their way, people who in many of these villages had been only one day liberated from the German yoke. Our men marched singing, with a smiling light in the eyes. They had done their job, and it was finished with the greatest victory in the world." (7)

Charles Montague described how the men responded to the end of war: "The day after the fighting ended I met hundreds of men who had been prisoners and broken out just before the armistice. They were coming back into our lines, almost starving, and some of them had died of hunger and exhaustion on the way; but they came along splendidly, marching in little groups under the command of the oldest soldier in each, with their horrible black uniforms as clean and neat as hard trying could make them, marching along very steady and smart and taking no notice of anybody. I thought I had never seen the British soldier to greater advantage." (8)

German soldiers understandably felt that their suffering had all been in vain. George Grosz remarked: "I thought the war would never end. And perhaps it never did, either. Peace was declared, but not all of us were drunk with joy or stricken blind. Very little changed fundamentally, except that the proud German soldier had turned into a defeated bundle of misery and the great German army had disintegrated. I was disappointed, not because we had lost the war but because our people had allowed it to go on for so many years, instead of heeding the few voices of protest against all that mass insanity and slaughter." (9)

Duff Cooper was on a train when he heard the news: "Two Flying Corps officers got in at Cambridge and said that they had received an official wireless to say that the armistice had been signed. As we got nearer London we saw flags flying and in some places cheering crowds... All London was in uproar - singing, cheering, waving flags. In spite of real delight I couldn't resist a feeling of profound melancholy, looking at the crowds of silly cheering people and thinking of the dead." (10)

Virginia Woolf was living in London at the time: "Twenty-five minutes ago the guns went off, announcing peace. A siren hooted on the river. They are hooting still. A few people ran back to look out of windows. A very cloudy still day, the smoke toppling over heavily towards the east; and that too wearing for a moment a look of something floating, waving, drooping. So far neither bells nor flags, but the wailing of sirens and intermittent guns." (11)

Four days later she wrote: "Peace is rapidly dissolving into the light of common day. You can go to London without meeting more than two drunk soldiers; only an occasional crowd blocks the street. But mentally the change is marked too. Instead of feeling that the whole people, willing or not, were concentrated on a single point, one feels now that the whole bunch has burst asunder and flown off with the utmost vigour in different directions. We are once more a nation of individuals." (12)

Primary Sources

(1) Charles Montague, letter to Francis Dodd (18th November, 1918)

It has been a wonderful progress eastwards, always coming into new towns and villages where the people rushed out, and shook hands and kissed us and sometimes offered us pieces of bread, thinking we must be half-starved like themselves and the German troops.

When the war ended I had the luck to be at our front at the very place from which the old army was forced to retreat in 1914, and it was great when eleven o'clock went and the Belgian civilians and we crowded together into the village square to rejoice. They played 'Tripperay' on the parish church bells and we all sang the two National Anthems and cheered King Albert and felt it had all been worthwhile.

The day after the fighting ended I met hundreds of men who had been prisoners and broken out just before the armistice. They were coming back into our lines, almost starving, and some of them had died of hunger and exhaustion on the way; but they came along splendidly, marching in little groups under the command of the oldest soldier in each, with their horrible black uniforms as clean and neat as hard trying could make them, marching along very steady and smart and taking no notice of anybody. I thought I had never seen the British soldier to greater advantage.

(2) Percival Phillips, Daily Express (12th November, 1918)

Just at eleven I came into the little town of Leuze, which had been one of the headquarters nearest the uncertain front. From the windows of all the houses round about, and even from the roofs, the inhabitants looked down on the troops and heard uncomprehendingly the words of the Colonel as he read from a sheet of paper the order that ended hostilities.

A trumpeter sounded the 'stand fast'. In the narrow high-street at one end of the little square were other troops moving slowly forward, and as the notes of the bugle rose clear and crisp above the rumble of the gun-carriages these men turned with smiles of wonder and delight and shouted to each other 'The war's over'.

The band played 'God save the King'. None heard it without a quiver of emotion. The mud-stained troops paused in the crowded street, the hum of traffic was stilled. A rippling cheer was drowned in the first notes of the Belgian hymn; the 'Marseillaise' succeeded it, and the army of each ally was thus saluted in turn. I do not think that any one heard the few choked words of the old mayor when he tried to voice the thanks of Belgium for this day of happiness.

(3) Philip Gibbs, Daily Chronicle (12th November, 1918)

Our troops knew this morning that the Armistice had been signed. I stopped on my way to Mons outside brigade headquarters, and an officer said, 'Hostilities will cease at eleven o'clock'. All the way to Mons there were columns of troops on the march, and their bands played ahead of them, and almost every man had a flag on his rifle, the red, white, and blue of France, the red, yellow, and black of Belgium. They wore flowers in their caps and in their tunics, red and white chrysanthemums given them by the crowds of people who cheered them on their way, people who in many of these villages had been only one day liberated from the German yoke. Our men marched singing, with a smiling light in the eyes. They had done their job, and it was finished with the greatest victory in the world.

(4) Sergeant T. Grady, USA Army, diary entry (11th November, 1918)

Cold and raining. Runner in at 10.30 with order to cease firing at 11.000 a.m. Firing continued and we stood by. 306th Machine-Gun Company on my right lost twelve men at 10.55, when a high explosive landed in their position. At 11.00 sharp the shelling ceased on both sides and we don't know what to say. Captain came up and told us the war was over. We were dumfounded and finally came to and cheered - and it went down the line like wildfire. I reported Jones' death and marked his grave. Captain conducted a prayer and cried like a baby.

(5) George Grosz, Autobiography of George Grosz (1955)

I thought the war would never end. And perhaps it never did, either. Peace was declared, but not all of us were drunk with joy or stricken blind. Very little changed fundamentally, except that the proud German soldier had turned into a defeated bundle of misery and the great German army had disintegrated.

I was disappointed, not because we had lost the war but because our people had allowed it to go on for so many years, instead of heeding the few voices of protest against all that mass insanity and slaughter.

(6) Malcolm Cowley was an ambulance driver in France when the war came to an end. He wrote about his feelings in the Exile's Return (1934)

When we first heard of the Armistice we felt a sense of relief too deep to express, and we all got drunk. We had come through, we were still alive, and nobody at all would be killed tomorrow. The composite fatherland for which we had fought and in which some of us still believed - France, Italy, the Allies, our English homeland, democracy, the self- determination of small nations - had triumphed. We danced in the streets, embraced old women and pretty girls, swore blood brotherhood with soldiers in little bars, drank with our elbows locked in theirs, reeled through the streets with bottles of champagne, fell asleep somewhere. On the next day, after we got over our hangovers, we didn't know what to do, so we got drunk. But slowly, as the days went by, the intoxication passed, and the tears of joy: it appeared that our composite fatherland was dissolving into quarreling statesmen and oil and steel magnates. Our own nation had passed the Prohibition Amendment as if to publish a bill of separation between itself and ourselves; it wasn't our country any longer. Nevertheless we returned to it: there was nowhere else to go. We returned to New York, appropriately - to the homeland of the uprooted, where everyone you met came from another town and tried to forget it; where nobody seemed to have parents, or a past more distant than last night's swell party, or a future beyond the swell party this evening and the disillusioned book he would write tomorrow.

(7) Virginia Woolf, diary entry (11th November, 1918)

Twenty-five minutes ago the guns went off, announcing peace. A siren hooted on the river. They are hooting still. A few people ran back to look out of windows. A very cloudy still day, the smoke toppling over heavily towards the east; and that too wearing for a moment a look of something floating, waving, drooping. So far neither bells nor flags, but the wailing of sirens and intermittent guns.

(8) Michael McDonagh, diary entry (11th November, 1918)

Looking through my window I saw passers by stopping each other and exchanging remarks before hurrying on. They were obviously excited but unperturbed. I rushed out and inquired what was the matter. "The Armistice!" they exclaimed, "The War is over!"

I was stunned by the news, as if something highly improbable and difficult of belief had happened. It is not that what the papers have been saying about an Armistice had passed out of my mind, but that I had not expected the announcement of its success would have come so soon. Yet it was so. What is still more curious is that when I became fully seized of the tremendous nature of the event, though I was emotionally disturbed, I felt no joyous exultation. There was relief that the War was over, because it could not now end, as it might have done, in the crowning tragedy of the defeat of the Allies. I sorrowed for the millions of young men who had lost their lives; and perhaps more so for the living than for the dead - for the bereaved mothers and wives whose reawakened grief must in this hour of triumph be unbearably poignant. But what gave me the greatest shock was my feeling in regard to myself. A melancholy took possession of me when I came to realize, as I did quickly and keenly, that a great and unique episode in my life was past and gone, and, as I hoped as well as believed, would never be repeated. Our sense of the value of life and its excitements, so vividly heightened by the War, is, with one final leap of its flame today, about to expire in its ashes. Tomorrow we return to the monotonous and the humdrum. "So sad, so strange, the days that are no more!"

(9) Sydney Morning Herald (12th November, 1918)

The end of the war in the capitulation of Germany is an event so much greater in importance than any within the experience of the modern world that it is impossible to grasp its full significance. The most tragic chapter in the history of mankind is at last at an end. Hundreds and thousands of men will today be relieved of a constant burden of mental and physical suffering, hundreds of thousands of their kinsfolk will at last be free of the daily anxiety which has been theirs ever since their sons and brothers went into the firing line. There will be many whom this news of victory will not save from personal grief. The sounds of rejoicing cannot but bring some reminder of their loss. To them, however, the news of victory will mean more than to any others, since it will assure them that their sacrifice has not been in vain.

Every man who saw his duty and did it when the choice was before him has had his share in the destruction of the most maleficent Power that ever afflicted mankind. The Australian people will recognise that to them they owe their safety, that through them their honour stands high among the free peoples of the world. Peace that has been won by so much suffering and so many tears must be honoured by a new spirit of fraternity and public service. The flower of this generation has perished. Their loss is irreplaceable, but their sacrifice makes an unanswerable appeal for the democracy they have honoured and preserved.

(10) Virginia Woolf, diary entry (15th November, 1918)

Peace is rapidly dissolving into the light of common day. You can go to London without meeting more than two drunk soldiers; only an occasional crowd blocks the street. But mentally the change is marked too. Instead of feeling that the whole people, willing or not, were concentrated on a single point, one feels now that the whole bunch has burst asunder and flown off with the utmost vigour in different directions. We are once more a nation of individuals.

(11) Herbert Sulzbach, diary entry (13th November, 1918)

We now keep meeting small or large parties of British or French prisoners moving west on their way home. What a splendid mood they must be in compared with us.

In spite of it all, we can be proud of the performance we put up, and we shall always be proud of it. Never before has a nation, a single army, had the whole world against it and stood its ground against such overwhelming odds; had it been the other way round, this heroic performance could never have been achieved by any other nation. We protected our homeland from her enemies - they never pushed as far as German territory.

(12) Howard Spring worked in the Intelligence Department at General Headquarters in France during the First World War.

All through this time, I was doing what I had been doing as a newspaper reporter: I was a detached observer of a life in which I had no essential participation. Dullness without danger; an occasional heightening of excitement at second hand. In a regular routine fashion, all of us clerks were "mentioned in despatches" and awarded the Meritorious Service Medal, just as the junior officers were awarded the M.C. and the seniors the D.S.O. It was routine. If it fooled anybody, I don't think it fooled us - neither the M.S.M.s nor the D.S.O.s. I have always thought that if medals are to be awarded for the sort of work we did - whether to the junior clerks, who are the privates and corporals, or to the departmental managers, who are colonels and brigadier-generals - they should not be the same decorations as those awarded for service in the field. The only time my own life was near danger was on November 11th, 1918, when some Scottish troops blazed off a feu de joie, and a bullet passed in at one wall and out at another of a small canvas hut which I lived in.

(13) Henry Allingham, Last Post (2005)

When the war ended I was in Belgium. Naturally, everybody went mad - but I didn't. I took to my bed and had a good night's sleep. There were a good many men who never saw the morning because they all went crazy. If they had a rifle and bullets, they'd shoot, just to make a noise. The Very lights (a coloured flare fired from a pistol) went up all around, and people went crazy. I wasn't going to do that. I thought I'd get a good sleep while I could. When the rest came in the morning they were all over the place - but I was alright. We were supposed to move at eight o'clock but we didn't get away until eleven, because chaps were coming in in dribs and drabs. Then we got under way and we went through Belgium and into Germany, to the Rhine, and I got to Cologne. I remember going into the hotel opposite the cathedral. I spoke to the chef, who had worked in London for eight years before the war. He offered me something to eat; it was black and a bit smaller than an Oxo cube. Goodness knows what it was but it gave me indigestion for two hours afterwards.

(14) Frank Percy Crozier, A Brass Hat in No Man's Land (1930)

Only those men who actually march back from the battle line on 11th November, 1918, can ever know or realise the mixed feelings then in the hearts of combatants. We are dazed. When Germans, Frenchmen, Belgians, and Britishers rise and stretch at 11 a.m., in the presence of each other, with an inner feeling of insecurity, lest some one may "do the dirty," and be tempted to fire off a parting shot, they are dazed - for no fighting man worth his salt desired at that moment to do anything but forget the past and forge the future.

All the world over, where men and women congregated in large numbers they went mad. Not so the fighting men fresh from the line, dumped down in the liberated areas, where children beg for bread and grown-ups thank God for delivery.

While the stay-at-homes of victorious countries are dancing, and drinking in the capitals of Europe, and patting themselves on the back because they have won the war, Andrews, the valiant Andrews, thruster, fighter and man of action, is issuing his remaining mess stores personally to little children who have never seen or cannot remember a tin of fruit or known a Christmas party.

We march back to Croix.

Many of the men wear garlands, the gifts of grateful people to old warriors no longer in the first flush of youth, who have stuck it to the end, while some carry joy banners, seized as souvenirs from the cottage tops of hamlets.

Student Activities

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Sinking of the Lusitania (Answer Commentary)