The Roman Ampitheatre at Chester (original) (raw)

The Roman Amphitheatre

The Roman Amphitheatre which stands at the top of Newgate in Chester dates from around 86A.D. and is the largest yet excavated in the whole of the British Isles.

The Ampitheatre from the West

The amphitheatre stands by the site of the Roman fort of Deva, and was constructed shortly after the establishment of the fort to provide an entertainment centre and training ground for the troops of the 20th Legion stationed there. It is semi circular in form as only half of the structure has been excavated. The southern half of the structure still lies beneath buildings, some of which are themselves listed.

The Ampitheatre from the East

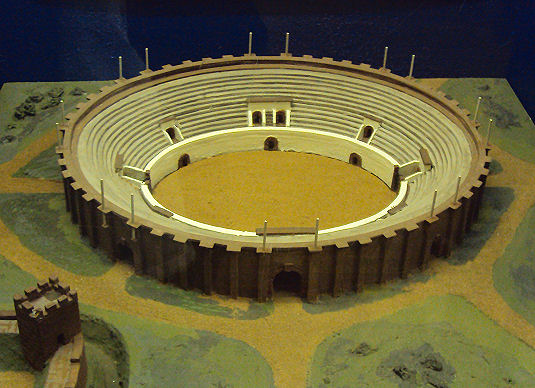

The structure consisted of a 40 feet (12 metre) high stone ellipse, 320 feet (98 metres) along the major axis by 286 feet (87 m) along the minor. The exits are positioned along the four points of the compass. Evidence of eight vaulted stairways, known as vomitoria, has been uncovered, which opened directly on to the street and served as entrances to the auditorium. As was the fashion with most Roman forts of the era, the amphitheatre was placed at the south east corner of the fort. Unlike other smaller, more basic amphitheatres in Britain, the one in Chester had proper seating for about 10,000 spectators on two storeys and about it stood a complex of dungeons, stables and food stands.

The Nemesium by the Northern Entrance of the Ampitheatre

The remains were discovered in June 1929 by W J Walrus Williams (1875-1971), an amateur archaeologist. Williams was examining a pit dug in the grounds of the Ursuline Convent for the installation of a heating system , when he noticed large pieces of masonry, which he assumed to be the remains of the amphitheatre which was known to have existed at Chester. Later excavations confirmed Williams' theory. Excavation of the Roman Amphitheatre began in 1939 but was halted at the outbreak of the Second World War. following the war, excavation did not resume until 1957 but even then could not be finished as the Victorian Dee house was still being used. The house was demolished in June 1958 and excavation of the site commenced in 1960, the Chester Amphitheatre was eventually opened to the public in August 1972.

Part of the Amphitheatre Mural by Gary Drostle

Chester Renaissance commissioned a trompe l'oeil mural in August 2010, to enable visitors to experience the illusion of a complete amphitheatre as well as showing how the original structure may have appeared. Archeologists advised internationally renowned artist Gary Drostle on the original construction and found artifacts from the site. The mural covers the 50 metre walkway wall.

Replica of the Shrine to Nemesis

Beside the amphitheatre stands a shrine to Nemesis, Roman godess of vengeance. The present altar is a replica; the original is kept at the Grosvenor Museum. The site is managed by English Heritage.

The Roman Arena

"When he saw the blood, it was though he has drunk a deep draught of savage passion. He fixed his eyes on the scene and took it in in all its frenzy......He watched and cheered and grew hot with excitement." St Augustine Confessions 6.8

"When he saw the blood, it was though he has drunk a deep draught of savage passion. He fixed his eyes on the scene and took it in in all its frenzy......He watched and cheered and grew hot with excitement." St Augustine Confessions 6.8

The spectacles watched in Roman amphitheatres, wild beast fights, public executions and gladiatorial combat, were not just bloodthirsty entertainment, they were rituals which expressed Roman values. Even the allocation of seats, with leading citizens at the front and slaves at the back, mirrored the strict organization of Roman society.

Wild Beast Fights

Bears, stags, bullls and boars would have been found in British amphitheatres replacing the elephants, lions and tigers that were seen in Rome. The killing of animals in staged fights was meant to reinforce the belief in man's domination over nature in a world where wild animals still posed a real threat. Archaeologists even dug up chicken bones and bits of pork ribs - the leftovers from snacks which were sold to the hungry crowd of spectators.

Crime and Retribution

Roman punishments were harsh and carried out publicly in order to deter future offenders and show that order was restored. As at Chester, amphitheatres often had a shrine to the goddess Nemesis (destiny), alike with her the Roman state held the power to reward or destroy. Human and animal remains have been unearthed at the Chester amphitheatre.

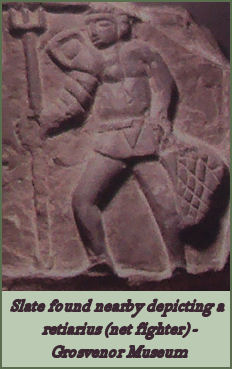

Gladiators

Gladiator fights were hugely popular and aroused deep passions. Gladiators were often prisoners of war or condemned slaves, reprieved and trained for the arena. Combat gave them literaly a new chance to win a new life by showing skill and courage, even in defeat. They reinforced the Roman military ethos, important in a garrison town like Chester.

Model of the Amphitheatre as it would have appeared in Roman times- from the Grosvenor Museum

A stone block with iron fittings was discovered at the centre of the Chester amphitheatre, which dates back to about AD100. It is similar to one depicted in a third century mosaic found at a Roman villa at Bignor, West Sussex, which shows two gladiators fighting. It is the third such stone block found at the Chester site and its location suggests the anchors were evenly spaced along the long axis of the arena to prevent gladiators from sheltering against the arena wall and thereby giving spectators the best possible view. Archaeologists cannot be certain as to which forms of gladiatorial combats were staged in Chester, it is believed there was a special type of gladiator called a bestiarius, who was trained to fight different types of animals.