Chicago ''L''.org: Operations - Lines - (original) (raw)

|

| |

| ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | |

| |

| ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | |

|

|

|---|

Kenwood branch

|

|---|

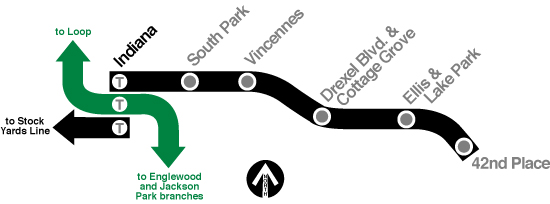

Legend:  Current Line w/Station .. Current Line w/Station ..  Current Line w/Former Transfer Station .. Current Line w/Former Transfer Station ..  Demolished Line w/Former Station .. Click on a station name to see that station's profile (where available) Demolished Line w/Former Station .. Click on a station name to see that station's profile (where available) |

Service Notes:

Date of Opening: 1907 Date of Abandonment: 1957 Length of Route: 1.25 miles (approx.) Number of Stations: 6 stations

History:

The story of the Kenwood Line (or "Kenwood branch", as it is interchangeably called) begins 43 years before it opened and with another railroad entirely. In 1864, the Union Stock Yards and Transit Company (USY&T) was chartered to build a central stock yards facility, and the next year that facility (which became the famous, sprawling Chicago Stock Yards) opened on a 320-acre tract between Halsted Avenue and Ashland Avenue, south of 39th Street. To serve the busy stock yards, the USY&T built a network of rail lines within the stock yards complex, as well as an east-west line paralleling and adjacent to 40th Street from the yards to the Illinois Central Railroad near 43rd Street and Oakenwald Avenue. It is this line that begins the story of the Kenwood branch.

Although this was largely intended as a freight line for interchange traffic between the yards and various connecting railroads, as early as 1882 passenger service was also being run there. Stations at Lake Park, Cottage Grove, Langely, Vincennes, Grand Boulevard (later South Park and now King Drive), Indiana, and Michigan were served by various trains, some acting as stock yards-kenwood locals, some offering service downtown to LaSalle Street Station, some Illinois Central runs going as far south as Riverdale, and by 1898 some stock yards shuttles to Indiana, so that passengers could transfer to the South Side Elevated there. The same year, the various railroads that owned and operated the trackage merged to form the Chicago Junction Railway.

The retaining walls for the new Kenwood branch/Chicago Junction Railway embankment are nearly complete in this view at Grand Boulevard (King Drive). The South Side Elevated is visible in the background. For a larger view, click here. (Photo from the Bruce G. Moffat Collection)

Kenwood passenger service continued until 1904, when the outside pressures allowed the "L" to enter into the story. On March 16, 1903, the Chicago City Council passed an ordinance requiring the elevation and grade separation of the 40th Street line. This was part of a larger effort by the city to eliminate grade crossings to increase safety and improve traffic flow all over the city. To protect themselves against possible financial hardship (the cost of the elevation was seen as very high, if not potentially ruinous). a subsidiary company, the Chicago Junction Railroad, was incorporated in 1902.

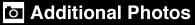

It was decided that the Chicago Junction Railway would not operate passenger service on the 40th Street line anymore. That responsibility was passed to the South Side Elevated, who would integrate the lines into the "L" system. The Chicago Junction Railroad would construct the elevated right-of-way for both the "L" and freight lines (which, except around Indiana station and the 42nd Place terminal, was the same right-of-way), provide stations, and acquire whatever other real estate would be needed for "L" service (except that for yards and terminals). The South Side Elevated was responsible for providing rolling stock, yards, a terminal, and an electrical distribution system (i.e. the third rail and associated power infrastructure). The Kenwood branch extended eastward from theIndiana station -- which was already located on an east-west zigzag along 40th Street in the largely north-south South Side "L" route -- to a terminal at 42nd Place and Oakenwald Avenue. Except for the 42nd Place terminal and yard and a short connection to the existing "L" structure at Indiana, the entire branch is on a solid-fill concrete-walled embankment shared with the Chicago Junction Railway.

Above: The Lake Park entrance to Ellis-Lake Park, seen in October 1955, was typical of the Kenwood embankment stations. (Photo by George Macak, from the Krambles-Peterson Archive)

Below: The Cottage Grove-Drexel platform. All those along the Kenwood branch, save for the 42nd Place terminal, were similar. For a larger view, click here. (Photo from the Bruce G. Moffat Collection)

On September 30, 1903, the Chicago Junction Railroad and the South Side Elevated signed a 50-year lease, with options for two 50-year renewals and an option to buy. One clause said that if the elevated failed to make lease payments to the Chicago Junction for a period of six months, it could seize the property and operate it on its own. This clause would become a major issue in later years, both for the Chicago Rapid Transit and for the CTA when the 50-year period (after operations began) was up in 1957.

Due to some construction delays, the Kenwood branch didn't open until September 20, 1907. The branch, which leaves the South Side main line at Indiana Avenue and 40th Street, is built on solid-fill embankment, except for short sections of steel elevated structure at the west end (where the line connects to the South Side Elevated) and42nd Place terminal and yard east of Lake Park Avenue. The embankment contained three tracks: the north track had no third rail and was for the Chicago Junction Railroad's freight trains, while the middle and south tracks had third rail and were for Kenwood branch trains.

Of the five stations on the branch (not including Indiana, which would make six), all but the 42nd Place terminal were of a similar, simple concrete-and-steel design. The station houses were built into the concrete embankment. Never lavish by any standards, their exterior's were plain concrete with three doors (the main double-doors in the center flanked by two smaller doors) decorated only by a simple pediment over each entrance. Inside, amenities were minimal or nonexistent. The walls were concrete or (usually badly water damaged) plaster with some wood moldings. Lighting was incandescent and the interior was broken up by naked steel I-beams. Only a simple wooden fare booth usually broke up the floor space. The two westernmost of these -- South Park and Vincennes -- had one entrance at their namesake street, while the other two -- Cottage Grove-Drexel and Lake Park-Ellis -- had two entrances at each of the station's namesake streets. All four stations had concrete island platforms and simple canopy latticework, which suited the largely unoccupied neighborhood at the time of its construction. The 42nd Place station at the far east end of the line was of a completely different design, both being the terminal and not in a solid embankment. The station was small and simple but of an attractive design, constructed of red brick with light brick highlights and was tucked under the elevated trestle. Its architecture was similar to those at Racine on the Englewood and 69th on the Normal Park branch of the South Side Elevated, possibly indicating the same architect. The island platform served two tracks on the west side of the sizable elevated yard.

Initially, base service consisted of 42nd Place-Indiana shuttles, alternated with 42nd Place-Loop locals. In rush, 42nd Place-Loop expresses were operated that skipped all stops between Indianaand 12th Street in the direction of peak travel, but made all stops in the opposite direction. In later years, some Kenwood-Stock Yards through trips were also run.

Later Developments

The Kenwood Line tracks crossing scenic Drexel Boulevard. Developers responded to the line by building new luxury apartments along Drexel (like those seen here) and by converting single-family homes into multifamily dwellings to meet the new desire for housing here. For a larger view, click here. (Photo from the Krambles-Peterson Collection)

Developers responded to the new line by building elegant new apartments (especially along scenic Drexel Boulevard) and converting single family dwellings into multifamily boarding houses. During this early development, the neighborhood was quite white collar, including many German Jews, Irish and English workers. By the 1930s, an increasing number of transients and single persons populated the neighborhood, followed by large numbers of African Americans in the 1940s. Stock Yards workers were common here too.

On November 3, 1913, after a long, protracted battle between the city and the elevated lines, through-routed crosstown service began and routing operations were modified. Kenwood trains were through-routed to the Ravenswood line during rush hours beginning November 4th, though because traffic was heavier on the Ravenswood than on Kenwood, some Rave trips still terminated in the Loop. Base service still consisted of Kenwood-Indiana shuttles, however.

The Kenwood branch saw little change in the following years. On February 23, 1931, the Chicago Rapid Transit made a few changes to crosstown service. The Wilson-Englewood and Ravenswood-Kenwood through-routes were swapped. To better adjust to the traffic patterns, these through-routes were only in effect in rush hour; at all other times, the trains terminated in the Loop. So, during rush hours Kenwood-Wilson locals were the order of the day, but Kenwood-Indiana shuttles still constituted base service on the branch.

With the opening of the State Street Subway on October 17, 1943 the Loop's severe congestion could finally be relieved. Jackson Park-Evanston/Howard and Englewood/Normal Park-Ravenswood trains were rerouted to the new subway. Englewood and Ravenswood trains were through-routed at all times from then on, as were the Kenwood-Wilson trains, which stayed on the Loop Elevated. At the same time, the ubiquitous Kenwood-Indiana shuttle was discontinued until 1949.

Decline

The decline of the Kenwood branch actually began long before the CTA took over in 1947. According to the lease between the Chicago Junction Railroad and the South Side Elevated (which the Chicago Rapid Transit Company inherited in 1924), if the elevated failed to make lease payments to the Chicago Junction for a period of six months, it could seize the property and operate it on its own. Technically, the CJRR owned the entire Kenwood Line -- right-of-way, embankment, tracks, stations, platforms -- except for the third rail, power distribution systems, fare collection equipment, and rolling stock.

Working the Kenwood shuttle on the last day of service, car 2925 pulls away fromCottage Grove-Drexel station on November 30, 1957. For a larger view, clickhere.(Photo by Jim Northcutt, from the Illinois Railway Museum Collection, courtesy of Peter Vesic)

The problems began in the 1930s. Both the CRT and CJ were in poor financial shape due to the Depression. The Chicago Junction began to defer maintenance on the line (as the owner, they were actually responsible for most upkeep) -- their basic response was, 'since we don't use these facilities, we don't care' -- and as a result the CRT was very unhappy and constantly battling with the railroad to keep their obligations. The Chicago Junction's response was that if the CRT was so concerned, they should start maintaining the branch themselves. The CRT responded by refusing to pay rent. Thus was the beginning of the end of the Kenwood line.

The Chicago Junction Railroad attempted to evict the CRT, but this was stayed by the Federal Bankruptcy Court. Eventually the CJ realized there was nothing they could really do -- not only did the court prevent the eviction, but they didn't own the rolling stock or power distribution to operate the line, should they have chosen to exercise that clause -- so they kept quiet, apart from an occasional brief to the court regarding the arrears in the rent. Meanwhile, the CRT did what minimal maintenance was needed to keep the line going, and deducted this from the rent owed.

In 1947, the Chicago Transit Authority took over the assets of the Chicago Rapid Transit Company and assumed operation of the "L" . When the CTA took over, the equation changed. The authority quickly decided that the Kenwood route had no real future, and since they also now controlled the surface system they could substitute the service with more economical buses.

In 1949, as part of the large North-South service revision, the Kenwood branch was made into a shuttle again, operating between42nd Place and Indiana. At this time, the three-track Indianastation was substantially altered to act as a large transfer station.

Inbound North-South through service was rerouted via the old center express track thru Indiana, with the northbound platform extended over the old northbound local track to serve it. Kenwood trains ended on a short remaining stub of the old northbound track. Although there was still a switch so that the Kenwood branch maintained a connection to the rest of the South Side elevated, the Kenwood was now substantially run only as a shuttle, berthing in its own special pocket at Indiana, with no real interaction with the rest of the system.

42nd Place terminal in less happy time, near the end of its life in 1957. By 1956, it was clear that the Kenwood branch's dropping ridership and deteriorating condition warranted action. A minimal station improvement program was contemplated that included removal of the north end of the station's island platform, the east station track, and possibly even the station house, leaving only a short platform and one stub track. For a larger view, click here.(Photos by Jim Northcutt, from the Illinois Railway Museum Collection, courtesy of Peter Vesic)

At the same time, the 42nd Place Yard was closed, along with the 42nd Place tower, and a spring switch crossover was installed. Car storage was moved to the old northbound track south of Indiana, although very few cars were actually needed for this shuttle service. In the last few years, the Kenwood and Stock Yards lines went through regular car assignment changes, receiving a rotation of whatever wood equipment was no longer needed on the rest of the system and had become orphaned. The shuttle used South Side Elevated motors for a while, then Northwestern open-end motors, and finally Metropolitan Elevated monitor-roof motor cars were used. As each car type was retired, another "newer" wood series came in to replace it (although none of these cars would really be called "new" by this point) until that type was retired.

Meanwhile, the Chicago Junction started pestering the CTA for rent again. The CTA could hardly plead poverty, so instead they claimed that the rent money was being used for necessary repairs. The local politicians in the early 1950's were very much on CTA's side regarding the Kenwood line, but the area went thru an essentially complete population changeover within a year or two in the mid-1950s, and the new arrivals either didn't care as much about the fate of the line or were not politically-empowered enough for anyone to care. By this time, the line was a shuttle with poor service, old cars, and deteriorating stations that few people had any inclination or desire to use. The additional pressure from the Chicago Junction for the resumption of rent payment helped cement CTA's decision to get out.

By 1956, it was clear that the Kenwood branch's dropping ridership and deteriorating condition warranted action. The Chicago Junction demanded that the CTA resume rental payments of 100,000yearlyandgavethemonlyuntilMay1,1956toagree,yetCTA′soperatinglosesonthelinehadbeen100,000 yearly and gave them only until May 1, 1956 to agree, yet CTA's operating loses on the line had been 100,000yearlyandgavethemonlyuntilMay1,1956toagree,yetCTA′soperatinglosesonthelinehadbeen200,000 a year. All hope was not lost that the branch might somehow be salvaged through some sort of revamp to make the line more cost-effective. Three plans were formulated for how to continue service -- purchasing the route from the Chicago Junction Railway, leasing it from the CJRwy, and purchase by an outside agency for CTA use -- but all of these included modernization of the Kenwood stations. As part of a modernization plan covering both the Kenwood and Stock Yards Lines, drawings dated July 13, 1956 show that the CTA planned to minimize and streamline the stations to achieve maximize usage with as little operations costs as possible. At 42nd Place, the yard would have been removed, along with the north end of the station's island platform, the east station track, and possibly even the station house, leaving only a short platform and one stub track. At the dual-entrance stations, one of the entrances would have been sealed off completely (Ellis and Drexel would have been the victims). At the other station entrances, the two doors to each side were to be sealed with transite and the doors of the center passage were to be removed. Floor-to-ceiling cornerless transit walls were to be used to partition off the interior of the station house, creating only a passageway from the door up to the stairs to the platform. Lamps were to be upgraded to a higher wattage for better security and new fare controls were to be installed. Only half the platform and canopy were to be retained.

Mayor Daley attempted to step in and mediate between the CTA and the Chicago Junction, hammering out an agreement that allowed CTA to continue service for a token rent of $1,000 per month until July 1957, by which time it was hoped a final agreement could be negotiated. Ultimately the low ridership, high cost of improvement and unreasonable rent payments caused the branch to close on November 30, 1957, upon the expiration of the original 50-year lease. The closure of the Kenwood Line also removed the last of the elevated's wooden cars from passenger service.

After Abandonment

After the Kenwood service was abandoned, all of the stations were sealed (with brick at street-level and with steel plates over the stairs on the platforms), but by-in-large the line was left intact. The Chicago Junction continued to use their track for freight, but their days were numbered as well, since their main customer, the stock yards, were closing. The single freight track stayed intact for several years, at least through the mid-1960s.

Ownership of the right-of-way was assumed by a number of railroads over the years, including the Penn Central, Conrail, and CSX. Penn Central occasionally used the line as far east as King Drive to access a warehouse as late as the early 1980s, when the warehouse closed and the tracks east of the Rock Island (near Federal Street) were removed. Any freight traffic over the section formally shared with the Kenwood has long since ceased, through some of the same line to the west is still used by CSX and Canadian National (the bridges over the Dan Ryan Expressway are between Pershing Road and Root Street).

Almost the entire Kenwood embankment is still intact. The steel elevated structures at Indiana and 42nd Place have long since been removed, the section of the embankment between Cottage Grove and Drexel Boulevard has been removed, and the steel bridges over the street crossings are gone, but the rest is still in place today.

Kenwood of the Past | Kenwood Today

|

42ndPlaceYard01.jpg(92k) The compact size of the 42nd Place yard is evident in this view, looking southeast with Lake Michigan in the background. The station platform is on the right. Note the small bow trolleys on top of the cars, needed to make contact with the overhead wires that powered the 61st Street Yard further south.(Photo from the Chicago Transit Authority Collection) |

|---|

Kenwood Today

The following is a series of photos taken in 2000 by railfan William Davidson. They are a fairly compete look at the entire length of the Kenwood Line as it appeared at the millennium, over 40 years after being out-of-service. Says Davidson,

"I have always been fascinated with CTA operations as long as I can remember. My father is a retired CTA motorman and every Saturday I would ride at least 2 trips with him while he motored the train. He worked on the Howard-Jackson Park and Englewood Lines. I started riding with around 7 yrs of age until about 18 when my first job after high school took scheduled me to work on Saturdays. I grew up on 37th and Wabash and had seen the CJR r-o-w countless times. However I had only seen limited freight service going to now defunct factories and had not thought much more about it. I noticed a single track elevated structure at 40th and Prairie leading to the r-o-w. I asked my father when did CTA use that and what was it for and he told me and old line ran there before my time. That only peeked my curiosity. When I was old enough to drive I followed the r-o-w to lake park street and remember there was a bridge that lead the freight service to the ICC RR at 42nd street."

The map below shows the length of the Kenwood Line, with the Green Line and surrounding streets included as reference points. The location of each photo is denoted by a " " symbol, with the arrow pointing in the direction the camera is looking. Each photo will appear in a popup window.

" symbol, with the arrow pointing in the direction the camera is looking. Each photo will appear in a popup window.

Additional Current Kenwood Photos

|

southpark02.jpg(112k) This view looks northeast in December 2002 at the abandoned entrance to the South Parkway station within the embankment of the former Kenwood elevated and Chicago Junction freight line. The boarded up building on the left opened in 1917 as the Peerless Theater -- located at 3955 S. Grand Blvd. -- one of the city's countless neighborhood movie theaters. It was later called the "Park Theater" before being closed.(Photo by John Smatlak) |

|---|---|

|

KenwoodSubstation.jpg(78k) The Kenwood branch substation is seen here looking northwest on 40th Street in December 2002. The branch's substation building still standing, despite being out of service for almost 50 years, along the ROW near 40th and Langley. The embankment is just out of frame to the right, and behind the building.(Photo by John Smatlak) |

|

|

|---|