City Mayors: Business Improvement Districts (original) (raw)

Business Improvement Districts

are unashamedly business-led By Peter Williams, The Means*

16 January 2010: As cities and towns become ever more populated, the debate on the way they are managed takes on an increasing urgency. With so many other priorities for the public purse the prospect of identifying a variety of income streams is attractive. One mechanism for so doing are Business Improvement Districts (BIDs). The growing interest in them globally has fuelled the debate. What are the concerns surrounding legitimacy? Is the model internationally transferable, or is it culturally bound?

The genesis of Business Improvement Districts is usually associated with North America, with the first sightings in Canada. The model has since spread to other English-speaking countries, such as South Africa, Ireland and the UK. There is growing interest in mainland Europe – with Germany and the Netherlands in the vanguard.

The adoption of BIDs in the UK should be seen in the wider history of town centre management. For over twenty years there has been significant and widespread interest in different approaches to town centre management. The focus has progressively broadened to the point where we now speak of the wider agenda of ‘place management’. BIDs form part of this growth, while offering a distinct and different approach.

Despite important variations between countries and states, categorisation as a BID implies a specific set of characteristics:

• BIDs are established through a ballot of those who will be expected to pay the levy; • BIDs are authorised by local governments based on local plans reflecting the priorities of those who will be sharing the expenses; • BID plans authorise management organisations to carry out a prescribed range of projects and service. A board of directors oversees the work and is principally composed of private sector people with some government representation; • BID plans typically are authorised for a maximum of five years and may be renewed at the end of the BID term; • Local governments must approve a compulsory charge on the benefiting businesses (or properties in the US ) that is accepted as fair and adequate to their needs; • Most employ a professional person or a small staff for day to day operations and to help businesses.

The most significant feature of the BID model for the UK is in the way that it generates reliable revenue. Critically the BID model came at a time when the ‘voluntarism’ that underpinned the funding of town and city centre partnerships was beginning to be tested. The partnership model was becoming a victim of its own success. Multiple retailers and other centre occupiers had begun to flinch at the cumulative costs of supporting partnerships in up to 400 centres. This inflamed an ongoing grievance against ‘free-loaders’ who received the benefits but didn’t contribute.

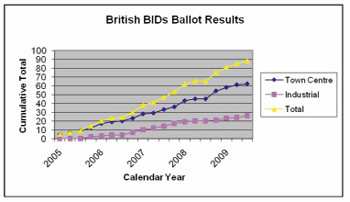

Since the enactment of the UK BIDs legislation in 2004 the development of BIDs has exceeded the expectation of most. To date there have been in excess of 120 ballots resulting in 88 BIDs.The pattern of development has been characterised as ‘waves’ – with commercial and town centres BIDs being supplemented by a growing number of industrial estate BIDs – but there is no indication of the growth curve abating. With the more obvious locations already developed, a ‘third wave’ of BIDs is now underway, and includes more marginal locations where property values are low.

Since the enactment of the UK BIDs legislation in 2004 the development of BIDs has exceeded the expectation of most. To date there have been in excess of 120 ballots resulting in 88 BIDs.The pattern of development has been characterised as ‘waves’ – with commercial and town centres BIDs being supplemented by a growing number of industrial estate BIDs – but there is no indication of the growth curve abating. With the more obvious locations already developed, a ‘third wave’ of BIDs is now underway, and includes more marginal locations where property values are low.

Globally the BID industry remains relatively immature. And little work has been done to throw light on what future pattern of global BID development we might expect.

Although successful BIDs typically rely on there being a degree of ‘organisation’ in a commercial centres, there are a variety of other factors that determine success or otherwise. In assessing BID feasibility in a number of locations, The Means has developed its own matrix of appraisal criteria. These are applied to the whole of a potential area as well as to smaller ‘zones’ within it:

Sustainability Is the revenue generated from the levy in proportion to (or in excess of) the revenue required to service the area in question?

Viability Can the levy be set at a reasonable level and still generate adequate funds for the BID? (At this point no-one has developed a model that sets the cost of running a BID against, say, the size of each area.)

Marketability What is the likelihood of winning a BID referendum? The costs of marketing the BID and running the referendum need to be in reasonable proportion to the eventual levy outturn. There needs to be an adequate number of businesses, which will directly benefit from the BID. Broadly, it is assumed that shops, restaurants, sports and leisure facilities, arts and culture facilities will reap a greater reward in terms of increased business. Offices and most other types of property will reap a lesser reward in this respect, but will benefit in terms of greater employee and client satisfaction.

Do-ability

Can BID services complement (or ‘join up’ with) existing services in such a way as to make a significant difference? Considerations:

• Is there a ‘gateway’ area which can be improved?

• Are there streets that could benefit from improvements?

• Is there a landmark visitor attraction which can be better serviced?

• Is there a pressing social/environmental issue which can be addressed?

Social responsibility Businesses can work to deliver social/educational programmes to the communities in which they are located, particularly when there might be benefits in terms of reduced crime and anti-social behaviour. This would give preference to areas with a residential population, particularly ones, which suffer from social exclusion. (See Case Study)

While we are convinced that many locations will meet these criteria, doubts remain about how the growth in the number of BIDs can be sustained after the more ‘obvious’ locations have considered them. What are the impediments to BID development going forward? We have identified three broad challenges which may restrain or arrest their advance, and considered what the remedies might be.

Absence of catalysts An important feature of BIDs is that they are private sector-led. However the public sector has played an indispensable role in acting as the catalyst to start the process in different locations, often providing the up-front risk finance. While there is provision in the BIDs regulations to reclaim start up/campaign costs from the BID levy that would only be possible in the event of a successful vote. There is little evidence of businesses being prepared to forward fund BID development.

Equally the earliest BIDs emerged from supportive public sector or trade association-driven learning networks such as those operated by the UK Association of Town Centre Management, The Circle Initiative, Society of London Manufacturers, Scottish BIDs, and East Midlands Academy. Further BID development will depend to a large extent on other agencies being prepared to follow this route.

Financial efficiency The economic downturn has hit the retail High Street particularly hard. Businesses feeling the pinch must see clear value for money in the BID proposition. Equally they should only have to pay what they can afford (the ‘viability’ criterion in our assessment matrix). So the BID business plan is not just about what programme is required but also what programme is affordable. In addition BIDs must appear lean to their constituencies from the outset, finding ways to minimise overheads and maximise investment in services.

In response to this challenge we have identified a number of adaptations to the BID model, which could be customized to meet particular requirements. We refer to these as:-

• Cluster BIDs • Satellite BIDs • Light BIDs

We have also considered a further, alternative option, which accords a much greater role to the public sector. This might form a stepping-stone or an interim phase ahead of full BID status. We refer to it as a Proto-BID.

Uni-dimensionalism Increasingly BIDs are critiqued for their apparent lack of democratic accountability. They are portrayed as a form of corporatism with limited aims other than to drive up sales, and being established to serve one set of masters. To these charges have been added further concerns around the civil liberties agenda, encapsulated in the phrase ‘the privatisation of public space’.

BIDs need to be sensitive to this charge, examine their objectives and operations, and respond. Best practice in BIDs already provides a coherent and convincing riposte:

• Programme – while Clean, Green and Safe are still the staples, BIDs are stretching their programmes to include CSR, employment initiatives, smarter travel, area promotion, business networking & support, environmental performance and recycling. This broadening agenda widens the focus onto the so-called triple bottom line – people, profit, planet

• Place management – Centre users are not just ‘customers’. They include those of all ages, those visiting the library and town hall, for recreation and for business. However places do need active management. There is no reason to believe that they are civil by default. The informal policing of the past is not set to return. People are both less respectful of all levels of authority and less inclined to intervene. BIDs, contrary to being a threat are already playing a role in democratizing place management

• Partnership – BIDs need to be unashamedly business led. There are other structures designed to reflect and respond to other constituencies and there is no purpose in replicating these. However many BIDs have seen the advantages of including a wide range of interest in their governance structures – on boards and/or on sub-groups.

• Presentation – BIDs are still a relatively new phenomena in the UK. However the BIDs that exist have already illustrated how flexible a mechanism this can be in responding to local circumstances. While this is a real strength it has made it more difficult to develop a shared narrative. BIDs will accordingly need to take care about how they present themselves to the world.

The development of BIDs came at a time when – for the first time in human history – more of us live in urban rather than rural settings. The best cities and towns continue to grow and prosper attracting inhabitants at an accelerating rate, ironically threatening their own achievements. The rest are in decline, at great environmental and human cost. It would be wrong to think that interventions can be designed to solve all of our urban problems. However BIDs, properly configured, are surely part of the solution.

* The Means manages London's 'Better Bankside' Business Improvement District. The future of 'Better Bankside' will be decided in a business-only ballot in February 2010.