Culture of Togo - history, people, clothing, women, beliefs, food, customs, family, social (original) (raw)

- Countries and Their Cultures

- To-Z

- Culture of Togo

Culture Name

Togolese; Togolais

Alternative Names

Republic of Togo; Republique du Togo; Togoland

Orientation

Identification. Togo is named after the town of Togoville, where Gustav Nachtigal signed a treaty with Mlapa III in 1884, establishing a German protectorate. Togo is an Ewe (pronounced Ev'hé) word meaning "lake" or "lagoon." Since 1884, Togoland and later Togo became synonymous for the entire region under colonial control. The term Togolese first appeared after World War I, and the population increasingly identified with this term, culminating in 1960 with the choice of the Republic of Togo as the official name.

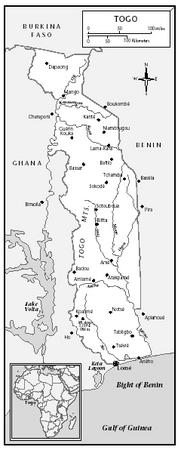

Location and Geography. Covering a total area (land and inland water) of 21,925 square miles (56,785 square kilometers), Togo extends 365 miles (587 kilometers) inland, 40 miles (64 kilometers) wide at the coast and 90 miles (145 kilometers) wide at its widest point. It is bordered by Ghana, Burkina Faso, and Benin.

Togo consists of six geographical regions. The coastal region is low-lying, sandy beach backed by the Tokoin plateau, a marsh, and the Lake Togo lagoon. The Tokoin (Ouatchi) Plateau extends about 20 miles (32 kilometers) inland at an elevation of 200 to 300 feet (61 to 91 meters). To the northeast, a higher tableland is drained by the Mono, Haho, Sio, and tributaries. The Atakora massif stretches diagonally across Togo from the town of Kpalime northeast; at different points it is known as the Danyi and Akposso Plateau, Fetish massif, Fazao mountain, Tchaoudjo massif, and Kabye mountains. The highest point is the Pic d'Agou at 3,937 feet (986 meters). North of the mountain range is the Oti plateau, a savanna land drained by the river of the same name. A higher, semi-arid region extends to the northern border.

The climate is tropical and humid for seven months, while the dry, desert winds of the Harmattan blow south from November to March, bringing cooler weather though little moisture. Annual temperatures vary between 75 and 98 degrees Fahrenheit (23 and 35 degrees Celsius) in the south and 65 to 100 degrees Fahrenheit (18 to 38 degrees Celsius) in the north.

The thirty Togolese ethnic groups are now found in all parts of the country, most notably in the capital Lomé, which is situated on the border with Ghana.

Demography. The population of Togo is estimated by the United Nations to be 5 million in 2000, with growth at approximately 3.5 percent per annum (though the last government census dates from 1981). One fifth of the population lives in Lomé, the capital. Kara, the second largest city, has approximately two hundred thousand inhabitants. Population density reached 42 per square mile (67 per square kilometer) in 1991, with 75 percent in rural villages.

Linguistic Affiliation. French is the official language of government, but both Ewe of the Kwa and Kabye of the Gur language families have semi-official status. Ewe has a much wider use than its ethnic boundaries, partly as a consequence of German colonial education policies. Mina—a constantly evolving melange of Ewe, French, English, and other languages—is the lingua franca of Lomé, of the coastal zone, and of commerce in general.

Symbolism. National symbols include Ablodé (an Ewe word meaning freedom and independence), immortalized in the national monument to independence; the African lion on the coat of arms (though long since extinct in Togo); and colorful Kente cloth,

Togo

originating in the Awatime region shared with neighboring Ghana.

History and Ethnic Relations

The population of the central mountains is perhaps the oldest in Togo, with recent archeological research dating the presence of the Tchamba, Bogou, and Bassar people as far back as the ninth century. Northern Mossi kingdoms date back to the thirteenth century. Ewe migration narratives from Nigeria and archaeological finds in the region of Notse put the earliest appearance of Ewe speakers at c. 1600. Other research suggests the Kabye and others were the last to settle in the Kara region coming from Kete-Krachi in Ghana as recently as two hundred fifty years ago. Parts of north Togo were for a long time under the influence of Islamic kingdoms, such as that of Umar Tal of the nineteenth century.

European presence began in the fifteenth century and became permanent from the sixteenth. Though the Danish, Dutch, Spanish, British, German, and French all sailed the coastal region, the Portuguese were the first to establish local economic control. For the next three centuries the area that is Togo today was sandwiched between the two powerful slave trading kingdoms of Ashanti and Dahomey. Consequently the Togolese population was overrepresented among those unfortunates sold into the trans-Atlantic slave trade. During the same period a growing Arab controlled trans-Saharan trade in slaves, kola, and gold passed through Togo.

Missionaries arrived in the mid-1800s and set up schools and churches in the regions of Ho (present-day Ghana), Kpalimé, and Agou. The Berlin Conference led to the annexation of Togo as a Schutzgebiet (protectorate) by the German Empire in 1884, under the leadership of Captain Gustav Nachtigal. Initially the treaty negotiated covered only the coastal region of about fifteen miles, though over the next fifteen years the German colonial administrators moved their capital from Zebe to Lomé and extended control north as far as present day Burkina Faso. The borders were finalized in treaties with France (1897) and Britain (1899).

German colonial rule consisted largely of export-oriented agricultural and infrastructural development, and frequent accounts of barbarity reached international attention. The most significant contribution was an system of roads and railroads built by German money and Togolese forced labor.

British and French troops invaded and captured German Togoland in 1914. For the duration of World War I, British troops controlled much of the region, including the capital, but with the Treaty of Versailles and the creation of the League of Nations Mandate system, Togoland was repartitioned. Officially in 1922, one third came under British control, and two-thirds under the administration of France (modern-day Togo), including the capital Lomé. After World War II, the mandates passed to the control of the United Nations (UN) Trusteeship in 1946. In 1956, in a UN-sponsored plebiscite, the British section voted to join the Gold Coast Colony as independent Ghana in 1957.

Emergence of the Nation. During the interwar period, several organizations—including the Cercle des Amitiés Françaises, the Duawo, and the Bund der deutschen Togoländer—organized and militated in public and private against French rule. The Cercle became the Committee for Togolese Unity Party (CUT), under the leadership of Sylvanus Olympio. The Togolese Party for Progress, led by Nicolas Grunitzky, offered a more conservative message. In 1956 France made French Togoland a republic within the French Union, with internal self-government. Grunitzky was made prime minister and against the wishes of the UN, France attempted to terminate the trusteeship. In a UN-sponsored election, the CUT won control of the legislature and Olympio became the country's first president on 27 April 1960. In 1963 Togo gained the dubious distinction of being the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to experience a military coup d'état.

National Identity. Until the dictatorship of Gnassingbé Eyadema, the southern Ewe culture predominated in all realms of life and was second only to the influence of French. After 1967, however, the president deigned to redress the southern bias in cultural, political, and social life, and to this end created authenticité, modeled on the same program of the Zaire dictator Mobutu. This movement attempted to highlight the many and diverse cultures of Togo, but resulted in reducing them to two only: that of the north and south. More recently, the idea of Togolese nationhood has become submerged to that of Kabye ethnicity.

Ethnic Relations. Ethnic tensions are minimal, despite the persistent murmurings of certain politicians. Political strife came to a head in 1991–1994 and did result in south against north violence and the reverse, with its concomitant refugees and resettlement, but Togo's thirty ethnic groups continue to mix and intermarry throughout the country.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

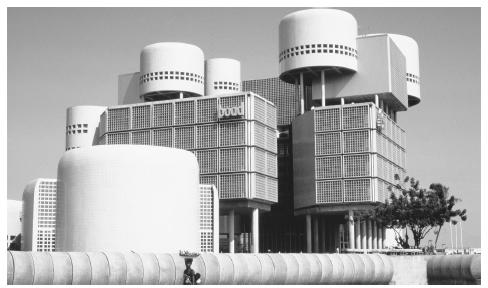

The city of Lomé and the coastal region are deeply influenced by the architectural programs of the successive colonial regimes. Vestiges of the German administrative buildings, several cathedrals and many churches, as well as private houses can be found throughout the country, though German influence was less pervasive in the north. The British period featured no architectural innovation, but more than forty years of French administration left its mark, most prominently in the work of Georges Coustereau. The works of this Frenchman are to be found throughout the country and include the national independence monument and an unusual church in the small town of Kpele-Ele.

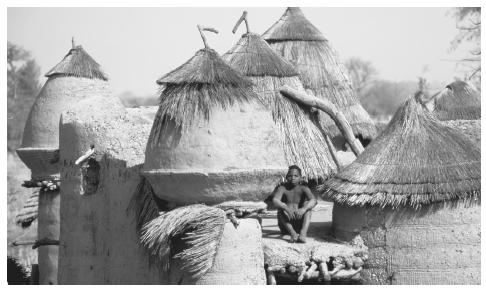

During the prosperous 1960s and 1970s, the president inaugurated an extravagant program, lavishing upon Lomé and his home town of Kara five-star hotels, a new port, and sports and government buildings. The skyline of Lomé is broken by four enormous skyscrapers, most prominently the five-star Hotel Deux Février. Since the economic decline of the 1980s and indebtedness, few new projects have succeeded. The Chinese government, however, funded the building of a forty-thousand-seat stadium, which opened in 2000. In the dire economic climate at the end of the twentieth century, private Togolese citizens invest their small incomes in private building, usually constructed by homemade concrete bricks. The vast majority, however, live in rural settings in a variety of traditional village designs: centralized, dispersed, on stilts, or in two-story conical mud huts like those of the Tamberma. Enclosures are gendered spaces, with the external kitchen area a female realm.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Togolese usually have two or three meals per day, each consisting largely of a starch product, such as cassava, maize, rice, yams, or plantains. A hot, spicy sauce is served with midday or evening meals, consisting of a protein—fish, goat, beans, or beef—and often rich in palm (red) oil or peanut paste. Fruits and vegetables, though readily available, are eaten more by the bourgeoisie. Traditional French staples, including baguettes, are mainstream in the cities.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Food does not serve a significant ceremonial function, except perhaps in terms of animist rituals, when the sacrificed animals are prepared, cooked, and served.

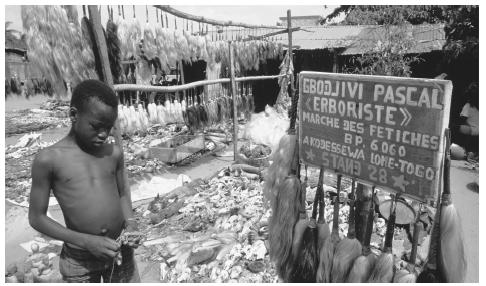

Hair hangs from poles, and skulls lay on the ground in a fetish market. Traditional vodou cults are popular.

Beer, gin, and sodabi (distilled palm wine) are, however, essential. Among wealthy middle-class Togolese, the usual French three- or four-course meals are always served at functions.

Basic Economy. Agriculture provides the mainstay of the economy, employing close to four-fifths of the active population. Farmers grow food for subsistence and for sale.

Land Tenure and Property. Private property exists in Togo alongside traditional community custodianship, and land is bought and sold under both systems. Private ownership of land began during the German period, as small parcels were purchased for commerce and for missions. The French continued this policy of gentle aggrandizement, but post-independence this was complicated by the president's illegal seizure and redistribution of plantations owned by his opponents. Thus, much land in the south, and particularly in the capital Lomé, remains the site of intense litigation, which takes place in the civil courts. Warnings are often written in red on the walls of land parcels to deter sale or deception.

Commercial Activities. Agricultural and manufactured products are sold both retail and wholesale in shops and markets. The informal economy is significant and is found in every town and village market, including the Assigamé (Grand Marché) in Lomé.

Major Industries. The 1990s saw most government industries privatized. Phosphates, run as a monopoly, remain Togo's largest industry, with electricity production a distant second. The once highly favored banking sector is in permanent decline, and tourism is insignificant. Togo has a small oil refinery, and animal husbandry, telecommunications, and information technology are growth industries. Togo has possibly the highest use of Internet and email services per capita in West Africa.

Trade. Togo's stagnant, underdeveloped economy is largely dependent on agricultural exports. In the mid 1990s, over 50 percent of Togo's exports were of four primary products—coffee, cocoa, cotton, and phosphates. Until the relaunching of ports in Cotonou and Lagos, Lomé was one of the busiest on the coast. The roads and rail infrastructure are rapidly declining, however, despite the launching of the Free Trade Zone in 1989.

France is by far Togo's largest trading partner. Fifty percent of imports from France are consumption goods, of which a minority are re-exported to Burkina and Niger. Forty-two percent of imports are of equipment, building, and agricultural supplies. Togo imports all its petroleum needs.

Division of Labor. Child labor has been ubiquitous, and in 1996 and 1998 several incidents of child slavery were exposed. Girls are more likely to work than go to school in much of Togo.

Professional positions are usually occupied by individuals who have had post-secondary school education. Successful business people may or may not have formal educations, but often they have relatives, friends, or patrons who helped finance their establishment.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. Society is divided along traditional and nontraditional lines. The elite includes kings, paramount chiefs, and vodou priests. The modern elite includes government functionaries, business professionals, and the educated. Poor rural families often send their children to city-living relatives for schooling or employment.

Symbols of Social Stratification. During the colonial period, all but the simplest clothing was considered a social distinguishing factor in villages, while brick houses and cars were in towns. During the last decades of the twentieth century, wealthy villagers could afford tin roofs and some even telephones, while in the cities, large houses, cable television, western dress, and restaurant dining were hallmarks of success.

Political Life

Government. The Fourth Republic provides for a constitution modeled on that of the Fifth French Republic, with the president, the prime minister, and the president of the National Assembly being the three chief posts. The constitution limits the president to two successive five-year terms, although he has amended the constitution frequently in the past.

Leadership and Political Officials. President Gnassingbe Eyadema came to power by force in 1967, though he was implicated in the assassination of the first president, Sylvanus Olympio, and played kingmaker from 1961 until coming to power. There were no obvious successors within his party—the Rassemblement du Peuple Togolais (RPT)—at the end of the twentieth century. After the 1991 national conference, Eyadema made the transition to being a democratically elected leader, though the 1998 presidential election was condemned internationally as flawed and fraudulent.

A one-party state from 1961 until 1991, Togo experienced a renaissance in multiparty politics, though political in-fighting beleaguer the chances of the Committee for Action and Renewal and the Union for Democratic Change (UDC). The leader of the UDC, Gilchrist Olympio, widely considered to have won the 1998 presidential election, lives in voluntary exile in Ghana.

Social Problems and Control. Large-scale social upheaval followed the political violence of 1992– 1993 and approximately one-third of the population moved to neighboring countries. With the political deadlock, relative calm returned. The cancellation of all international aid projects and withdrawal of most nongovernmental organizations, however, put strain on the economy. Unemployment, unsustainable wages, and poverty rose rapidly. Crime increased, particularly violent robberies and car-jackings. Most educational institutions were on strike throughout much of 1999–2000.

Military Activity. Togo has a small army and minimal naval and air forces. Eighty percent of the gendarmerie and 90 percent of the military are of the Kabye ethnic group. Most regularly go unpaid and set up ad hoc roadblocks to extort money. The French and Chinese were the leading suppliers of military hardware to Togo from the latter portion of the twentieth century to the present day.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

Welfare is almost nonexistent, though pensioners who paid contributions to the Francophone cooperative system continue to receive payments. Structural readjustment is hardly a success story, but a great number of state industries have been privatized under the guidance of the IMF/World Bank.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

Most nongovernmental and aid organizations quit Togo in the 1990s, with only Population Services International and Organizacion Ibero Americana de Cooperacion Inter Municipal (OICI) still operating throughout the country. Voluntary service organizations, such as Rotary, Lions, and Zonta continue to operate.

The Bank of Africa in Togo was constructed during a period of architectural innovation.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. Customary divisions of labor generally do not still hold in Togo, though men do most heavy construction work. Women perform almost all other manual labor in towns and villages, though less machine work, and control small market commerce.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Women, though having attained legal equality, remain unequal in all walks of life. Women and men are kept apart in most social gatherings. Women usually eat after men but before children. Discrimination against women in employment is common practice and widespread. Women have little place in political life and less in government programs, though there is a ministry allocated to women's and family affairs. Only women descended from ruling tribal families, successful businesswomen, or women politicians enjoy privileges equal to that of men, more won than granted. Togo recently banned the practice of female genital mutilation.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship. Traditional systems of social organization are significant in the daily lives of Togolese. Kinship systems provide networks for support and are visible during all major life-cycle ceremonies.

Marriage. Marriage practices vary throughout Togo according to the ethnic group, though organized religions and the State have altered the ceremonies of even the most secluded villages. Social disapproval of ethnic exogamy is lessening, though the government unofficially discourages it. Marriage law follows French legal statutes and requires an appearance before a magistrate for all state apparatuses to be in effect. Customary marriages, without state sanction, are still widespread. A bride-wealth, but not a dowry, remains important throughout Togo. Polygyny is officially decreasing, though unofficial relationships uphold its role.

Domestic Unit. The basic family structure is extended, although nuclear family units are increasingly commonplace, particularly in urban areas. In most cases, the man is the supreme head of the household in all major decisions. In the absence of the husband, the wife's senior brother holds sway. The extended family has a redistributive economic base.

Inheritance. Inheritance laws follow French legal statutes in the case of a legal marriage. In the event of a customary marriage only, customary inheritance laws are enforced. Most ethnic groups in Togo are patrilineal by tradition or have become so as a consequence of colonization.

Kin Groups. Kinship is largely patrilineal throughout Togo and remains powerful even among Westernized, urban populations. Village and neighborhood chiefs remain integral to local dispute resolution.

Socialization

Infant Care. Infants are cared for by their mothers and female members of their households, including servants. Among some ethnic groups, infants are often only exposed to the father eight days after birth. Vaccination against all childhood diseases has been strongly encouraged by the government.

Child Rearing and Education. Until the age of five, children remain at home. Initiation ceremonies occur from this age and throughout adolescence. After the age of five, all children can commence school, providing they can pay the school fees. On average, boys are three times more likely to complete primary schooling than girls. This discrepancy increases into secondary schooling and is most marked in the rural central and northern regions.

Higher Education. Secondary schooling is more common in the south, and numerous private and public schools offer the French baccalaureate system. Often children are sent abroad during strikes. Togo has one university, located in the capital, and it offers first- and second-level degrees in the arts and sciences, as well as in medicine and law.

Etiquette

Public displays of affection are seldom. Men and boys hold hands, but not boys and girls. Courting remains private and is not generally arranged by parents except among some ethnic groups; for example, the Tchamba. Old people and village elders are highly esteemed, though the climate of political fear has brought the undue influence of youths. Eating is done most often with the right hand, though among the bourgeoisie flatware is prevalent. When guests arrive, water is offered and the traditional greeting—asking about the family and their health—ensues.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Since the inception of the mandate, freedom of religious worship has been protected by law. The French interpreted this to include animistic African religions, and this perhaps partly accounts for the popularity of traditional vodou cults and rituals.

Throughout the country, many different forms of Christianity and Islam are practiced. Roman Catholicism is the most prevalent form of Christianity. Various American Baptist sects, the Assemblies of God, Mormons, Jehovah's Witnesses, and Eckankar have been making inroads among urban and rural populations alike. Islam is virtually paramount in the north.

Religious Practitioners. Religious officials, whether Catholic priests or vodou sofo, are held in the highest esteem in both rural and urban settings. They are always invited to bless traditional ceremonies as well as building projects or any new initiative. Traditional healers also hold sway, and—in the wake of the AIDS epidemic—are regaining popularity.

Death and the Afterlife. A Togolese funeral is a most important event. Wildly extravagant (by Western standards), funeral celebrations are a daily occurrence. Marching bands, choirs, football tournaments, banquets, and stately services are as fundamental as an expensively decorated coffin. Funerals often take place over a month or more, and families frequently sell or mortgage land or homes to pay for the funeral of a beloved and elderly relative. If the person dies in an accident, however, or some other sudden tragedy (AIDS, for example), this is considered a "hot death," and the funeral services are concluded more quickly, with little circumstance.

Medicine and Health Care

Similar to other underdeveloped, tropical nations, Togo's population is challenged by numerous health problems, including parasitic, intestinal, nutritional, venereal, and respiratory diseases.

Public health problems are exacerbated by inadequate waste disposal, sewerage, drinking water, and food storage.

In the 1990s, life expectancy at birth was fifty-one years, though this is declining steeply with the onset of AIDS. Malaria, commonly referred to as palu, remains the leading cause of illness and death. Other common diseases include schistosomiasis, meningitis, tuberculosis, pneumonia, and HIV/AIDS.

Traditional healing methods and preparations continue to be the most widely used form of health

Houses like these in Tata village house a large number of Togolese citizens.

care in Togo. Every small town has an herbalist, and one market in Lomé specializes in the sale of medicinal herbs. Frequently medical treatments are coupled with visits to the local vodou house or fetish priest.

Secular Celebrations

Major state holidays are 1 January; the Fête Nationale, 13 January; Fête de la Libération Economique, 24 January; Fête de la Victoire, 24 April; May Day, 1 May; Day of the Martyrs, 21 June; and Day of Struggle, 23 September. 27 April, Independence Day, is not officially celebrated by President Eyadema and is frequently a day of opposition activity.

The Arts and Humanities

There is little government support for the arts in Togo, beyond the rudimentary presence of a Ministry of Culture and the poorly funded and maintained departments of the university. Private organizations include the Centre Culturel Français, the American Cultural Center, and the Goethe Institut.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

There is little government support for the physical and social sciences in Togo, beyond the existence of a Ministry for Scientific Research and Education. Private organizations and nongovernmental organizations provide various services, and a private academy of social sciences was created.

Bibliography

Agier, Michel. Commerce et sociabilité: les négociants soudanais du quartier zongo de Lomé (Togo), 1983.

Comhaire-Sylvain, Suzanne. Femmes de Lomé, 1982.

Cornevin, Robert. Histoire du Togo. 3d ed., 1969.

Decalo, Samuel. Historical Dictionary of Togo. 3d ed., 1996.

Delval, Raymond. Les Musulmans au Togo, 1980.

Gérard, Bernard. Lomé: capital du Togo, 1975.

Greene, Sandra. "Gender, Ethnicity, and Social Change on the Upper Slave Coast: A History of the Anlo-Ewe," in Cahiers d'Etudes African, 169:489–524, 1996.

Lawrance, Benjamin Nicholas. Most Obedient Servants: The Politics of Language in German Colonial Togo, 2000.

Marguerat, Yves. Lomé, les étapes de la croissance: Une Brève Histoire de la capitale du Togo, 1992.

——, et al. "Si Lomé m'etait contée . . . ": dialogues avec les vieux Loméens, 1992.

Piot, Charles. Remotely Global: Village Modernity in West Africa, 1999.

Prigent, Françoise. Encyclopédie nationale du Togo, 1979.

Rosenthal, Judy. Possession, Ecstasy and the Law: Spirit Possession in Ewe Vodou, 1998.

Sebald, Peter. Togo 1884–1914: Eine Geschichte der deutschen "Musterkolonie" auf der Grundlage amtlicher Quellen, 1987.

Spieth, Jakob. Die Ewe-Stmme: Material zur Kunde des Ewe Volkes in Deutsch-Togo, 1906.

Viering, Erich. Togo Singt ein neues Lied, 1967.

Winslow, Zachery. Togo, 1988.

Westermann, Dietrich. Die Glidyi-Ewe in Togo, 1935.

—B ENJAMIN N ICHOLAS L AWRANCE

Also read article about Togo from Wikipedia