Bonnie and Clyde (1967) (original) (raw)

Background

Bonnie and Clyde (1967) is one of the sixties' most talked-about, volatile, controversial crime/gangster films combining comedy, terror, love, and ferocious violence. It was produced by Warner Bros. - the studio responsible for the gangster films of the 1930s, and it seems appropriate that this innovative, revisionist film redefined and romanticized the crime/gangster genre and the depiction of screen violence forever.

Bonnie and Clyde (1967) is one of the sixties' most talked-about, volatile, controversial crime/gangster films combining comedy, terror, love, and ferocious violence. It was produced by Warner Bros. - the studio responsible for the gangster films of the 1930s, and it seems appropriate that this innovative, revisionist film redefined and romanticized the crime/gangster genre and the depiction of screen violence forever.

Its producer, 28 year-old Warren Beatty, was also its title-role star Clyde Barrow, and his co-star Bonnie Parker, newcomer Faye Dunaway, became a major screen actress as a result of her breakthrough in this influential film. Likewise, unknown Gene Hackman was recognized as a solid actor and went on to star in many substantial roles (his next major role was in The French Connection (1971)).

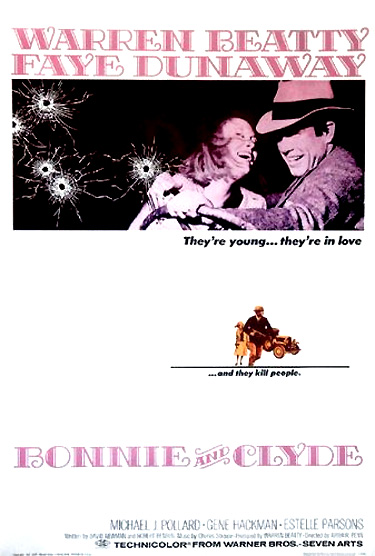

The story of Clyde's rise and self-destructive fall as an anti-authoritarian criminal gangster is clearly depicted. Both tragic outlaw figures exemplify 'innocents on the run' who cling to each other and try to function as a family. The film, with many opposing moods and shifts in tone (from serious to comical), is a cross between a gangster film, tragic-romantic traditions, a road film and buddy film, and screwball comedy. It exemplified many of the characteristics of experimental film-making from the French New Wave (Nouvelle Vague) movement. [Originally, the film was intended to be directed by Jean-Luc Godard or Francois Truffaut, who opted out and made Fahrenheit 451 (1966) instead.] The film's major poster about the infamous couple romanticized violence and proclaimed: "They're young...they're in love...and they kill people."

[Earlier films that recounted similar adventures of infamous, doomed lovers-on-the-run who are free and accountable to no one include Fritz Lang's _You Only Live Once (1937)_ with Henry Fonda and Sylvia Sidney, Joseph H. Lewis' cult classic Gun Crazy (1949) with John Dall and Peggy Cummins, Nicholas Ray's They Live By Night (1949) (remade by Robert Altman with its original title Thieves Like Us (1974) from Edward Anderson's source novel and starring Shelley Duvall and Keith Carradine), and The Bonnie Parker Story (1958) with Dorothy Provine and Jack Hogan. Later outlaw-couple films include B-movie Killers Three (1968) with Diane Varsi and Robert Walker, Jr., Terrence Malick's Badlands (1973), Ridley Scott's Thelma and Louise (1991), Kalifornia (1993), and Oliver Stone's Natural Born Killers (1994).]

The landmark film by post-WWII director Arthur Penn (who had previously directed The Miracle Worker (1962), The Train (1964) (uncredited and replaced by John Frankenheimer), and Mickey One (1965) - also with Beatty) was ultimately a popular and commercial success, but it was first widely denounced by film reviewers for glamorizing the two killers and only had mediocre box-office results. In the autumn of 1967, it opened and closed quite quickly - enough time for it to be indignantly criticized for its shocking violence, graphic bullet-ridden finale and for its blending of humorous farce with brutal killings. Then, after a period of reassessment, there were glowing reviews, critical acclaim, a Time Magazine cover story on December 8, 1967 (for a feature titled The New Cinema: Violence...Sex...Art...), and the film's re-release (with advertising that stressed its artistic merit) with a huge box-office take - and it was nominated for ten Academy Awards.

The film's screenplay by first-timers David Newman and Robert Benton (both editors at Esquire who had never written a screenplay) - a composite image of many early 20th century outlaws, was loosely based on the historical accounts of two 1930s Depression-era, social misfit bandits who terrorized the Midwest.

In the film, the two young and good-looking gangsters become counter-cultural, romantic fugitives and likable folk heroes with semi-mythic celebrity status, recalling Robin Hood and the outlaws of the West. However, the sordid and bleak reality behind the self-made publicity that the latter-day doomed couple generates (through poetry and photos) is also revealed. The Dust-Bowl period is effectively evoked, although the loose adaptation is also an inaccurate and fictionalized retelling of history. When they first met, the real Bonnie (19 years old) and Clyde (21 years old) weren't glamorous characters, and their romantic involvement was questionable. She was already the wife of an imprisoned murderer, and he was a petty thief and vagrant with numerous misdemeanors.

[The 'white trash' couple (described in the local newspaper as "the Southwest's most notorious bandit and his gun moll") first met in Texas in the early 1930s. Their brief, bloody crime spree (involving kidnapping and murders) ended on May 23, 1934 alongside state Highway 154 near Arcadia, Louisiana (the town nearest to the ambush site in north-central Louisiana), when the desperados were ambushed and killed by four Texas lawmen (led by Texas Ranger Frank Hamer), accompanied by Bienville Parish Sheriff Henderson Jordan and his deputy Prentiss Oakley. Their bullet-ridden vehicle was hit with 187 shots. In actuality, the 25 year-old Barrow and 23-year old Parker were armed and ready for the ambush when they were killed. Currently, Louisiana's largest outdoor flea market (held one weekend a month) originated in 1990 in Arcadia as Bonnie and Clyde Trade Days.]

Cartoon-style slapstick comedy [a tribute to Mack Sennett's silent films and Keystone Kops car chases and getaways] and banjo music (e.g. Foggy Mountain Breakdown from Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs, helped to introduce country music to mainstream films) and ballads accompany many of the film's scenes. The film's overall impact was heightened by its open examination of the gallant Clyde's sexuality-impotence and the link to his gun-toting violence. [To fulfill heartthrob Warren Beatty's image as a sex-symbol, he is finally able to consummate his love for Bonnie by film's end.]

Penn's masterpiece won two Oscars for Best Supporting Actress (Estelle Parsons in an over-the-top performance) and Best Cinematography (Burnett Guffey) for its great evocation of period detail, with eight other nods for Best Picture and Best Actor (producer/actor Warren Beatty), Best Actress (Faye Dunaway), Best Supporting Actor (Gene Hackman), Best Supporting Actor (Michael J. Pollard), Best Director (Arthur Penn), Best Story and Screenplay (Newman and Benton), and Best Costume Design (Theadora Van Runkle, who later worked on The Godfather, Part II (1974)). (Although Robert Towne, who later wrote Chinatown (1974), worked on the final form of the screenplay and served as a special consultant, he took no screen credit.)

In the late 1960s, the film's sympathetic, revolutionary characters and its social criticism appealed to anti-authority American youth who were part of the counter-cultural movement protesting the Vietnam War, the corrupt social order, and the U.S. government's role. [The same could be said for Mike Nichols' The Graduate (1967), another popular film released in the same year.] The restless couple's robberies of banks, viewed somewhat sympathetically by the rural dispossessed, occurred at a time when the institutions were 'robbing' and ruining indebted, Dust Bowl farmers. The robberies of the glamorous, thrill-seeking young couple - mostly innocent and minor at the beginning of their crime spree, unfortunately escalate into more violent and murderous escapades.

The influence of the film extended to commercial merchandise in the form of hairstyles, authentic period music of the 30s, and gangster retro-clothing (such as double-breasted suits, berets, fedoras, and the maxi-skirt). The film also permanently changed the form and substance of popular films - for better or worse.

The influence of the film extended to commercial merchandise in the form of hairstyles, authentic period music of the 30s, and gangster retro-clothing (such as double-breasted suits, berets, fedoras, and the maxi-skirt). The film also permanently changed the form and substance of popular films - for better or worse.

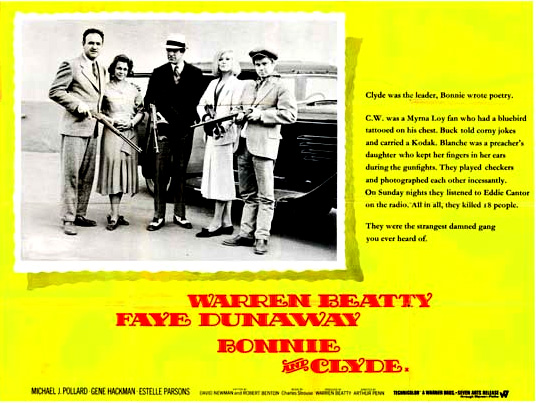

Lobby cards for the film described its main elements:

Clyde was the leader. Bonnie wrote poetry.

C.W. was a Myrna Loy fan who had a bluebird tattooed on his chest. Buck told corny jokes and carried a Kodak. Blanche was a preacher's daughter who kept her fingers in her ears during the gunfights. They played checkers and photographed each other incessantly. On Sunday nights they listened to Eddie Cantor on the radio. All in all, they killed 18 people.

They were the strangest damned gang you ever heard of.

Another lobby poster described their first auspicious meeting:

They met in 1930. She was stark naked, yelling at him out the window while he tried to steal her mother's car. In a matter of minutes they robbed a store, fired a few shots, and then stole somebody else's car. At that point, they had not yet been introduced.

Plot Synopsis

Following a golden, old-style Warner Bros shield, grainy, unglamorous, blurry, sepia-toned snapshots of the Barrow and Parker families (at the time of Bonnie and Clyde's childhood) play on a black background during the film's opening, accompanied by the loud clicking sound of a camera shutter. The credit titles are interspersed with flashes of more semi-documentary, brownish-tinged pictures. The text of the major credits fade from white to blood red on the dark background. 30's hand-cranked phonographic music (Rudy Vallee's popular love song of the period Deep Night) is faintly heard - a haunting omen from another era. The snapshot immediately preceding "DIRECTED BY ARTHUR PENN" is of three gunmen kneeling - making an unconscious connection between camera shots and fatal gunshots. The pictures of the Hollywood stars displace the unglamorous, 1930s pictures of the historic pair - the last two title cards describe the film's major protagonists:

- BONNIE PARKER - was born in Rowena, Texas, 1910 and then moved to West Dallas. In 1931 she worked in a cafe before beginning her career in crime.

- CLYDE BARROW - was born to a family of sharecroppers. As a young man he became a small-time thief and robbed a gas station. He served two years for armed robbery and was released on good behavior in 1931.

The last title card dissolves into a colorful closeup of red, luscious lips (that are being licked after lipstick has been applied). The immense lips belong to blonde Bonnie Parker (Faye Dunaway) - a bored, beautiful, and sexually-frustrated, Depression-era Texas cafe waitress who is naked and narcissistically primping in front of a mirror. It is a spring day in the early 1930s in Depression-affected West Dallas, Texas.

She is in her low-income frame house, and she is pouting - despairing of her unattractive, narrow existence in a tawdry environment. Aching from the enforced oppression of her confining room (and life), Bonnie flings herself down on her bed - appearing to be trapped behind the bars of the bedframe. Frustrated, she repeatedly strikes the cage surrounding her. In a closeup, her eyes reflect her torment. As she rises and goes behind a dressing screen, the camera reveals the top of her bureau - it is humbly decorated with a small, vulgar collection of porcelain figurines and a rag doll, and a few photographs are tacked on the drab wall.

Then, she looks out the screen of her second floor window and sees a furtive young man casing the area and contemplating hotwiring and stealing her mother's car in front of their yard. When she catches him in the act - she speaks the first line in the film:

Hey boy, what you doin' with my Mama's car?

When he is caught, he spins around in astonishment, looks up toward the window - obviously catching a glimpse of Bonnie's naked body temptingly framed there, and smirks. The camera exchanges shots between them. Drawn to the feeling of intense excitement and his apparent potency, she calls out: "Wait there!," hastily throws on some clothes from her closet, and urgently descends in loud clunky steps down the dark stairs (in a low-angled shot pointing upward) to meet the handsomely-dressed drifter named Clyde Barrow (Warren Beatty) with a white fedora. When she gets down to the outside porch (a sign behind her advertises "WASH TAKEN IN HERE"), she boldly tells him: "Ain't you ashamed? You're tryin' to steal an ol' lady's automobile." Before their posturing, arrogant battle of wits and sarcastic repartee, he proposes to treat her to a Coke in town.

When she flippantly tells him that she is "goin' to work anyway," they both talk with flirtatious tones during their sidewalk stroll (tracked by the camera with multiple stops and starts) and discover each other's "line of work" - she's a cheap cafe waitress and he's an ex-con for armed robbery:

Clyde: What kind of work do ya do?

Bonnie: None of your business.

Clyde (flattering): I'll bet you're a movie star? Huh? A lady mechanic?

Bonnie (amused): No.

Clyde: A maid?

Bonnie: (She halts) What do you think I am?

Clyde (realistically and accurately): A waitress.

Bonnie: (Long silence when she grows sullen, and then begins walking again.) What line of work are you in, when you're not stealin' cars?

Clyde: Well, I'll tell ya, uh, I'm lookin' for suitable employment right at the moment.

Bonnie: Yeah, but what did ya do before?

Clyde: I was, uh, I was in State Prison.

Bonnie: State Prison! (She halts again)

Clyde: Uh-huh.

Bonnie: Well, I guess, uh, some littl' ol' lady wasn't so nice.

Clyde: (expressed as part of a tough guy act) It was armed robbery.

Bonnie: My, my. The things that turn up in the street these days.

In the small, rural, Southwest Texas town where they walk along the empty main street (except for one elderly Negro sitting on a bench in front of a barber shop), Clyde asks her about her dull life after passing the closed-down movie theatre and other mostly-deserted shops: "Whatcha all do for a good time around here - listen to the grass grow?" In a display of unconventional, daring bravado, he points down to his right foot and brags to her that he once chopped two toes off with an axe "to get off of work detail" in state prison. [His awkward limp is evident throughout the film.] She declines to look at his dirty feet when he volunteers to demonstrate, but still wonders: "Boy, did you really do that?"

With a matchstick in his mouth, Clyde guzzles from an upturned Coke bottle (shot at an upward angle as a phallic symbol) that he has bought from a run-down gas station's soft drink chest up the street. Both of them drink from their Coke bottles in the next shot - emphasizing their growing intimacy and affinity for each other. And then she asks what "armed robbery" is like, instantly intrigued and charmed by his recklessness, but knowing that he is a liar. To prove that he isn't a "faker," he takes his gun out from inside his jacket in his right hand, while holding his Coke bottle in his left. Clyde shows her his large pistol pointing upwards at hip level, a second phallic symbol of his manhood, as he bounces the wooden match between his teeth. She looks down at the gun - at first repulsed, but then erotically fascinated, hypnotized and aroused by his assertive show of banditry and dangerousness. After tentatively and suggestively touching (fondling and caressing in a masturbatory way) the barrel of the gun, she goads him on to be her liberating hero by daring him with a sexually-loaded line: "But you wouldn't have the gumption to use it." The matchstick stands erect between Clyde's lips. To spontaneously impress her as part of the sexual dare and to prove his courage, he lets her witness his nonchalant, impulsive robbery of Ritts Groceries in the small town ("You keep your eyes open") - his first grocery-store robbery. In a long-shot, he strides across the vacant street - the camera remains with her as Bonnie stays outside and watches him from the middle of the street.

After a long moment of silence during the heist inside the store (off-screen), he emerges with a wad of bills in his left hand and his gun in his right hand. He awakens the unnatural quiet of the tiny town with one sharp crack of his revolver - he announces his own exhilarated manhood by shooting his weapon noisily into the air above the head of the dumbfounded store owner. Bonnie jumps into a car parked on the street, while he hot-wires it for their getaway. They introduce themselves formally to each other:

Bonnie: Hey, what's your name anyhow?

Clyde: Clyde Barrow.

Bonnie: Hi, I'm Bonnie Parker. Pleased to meet ya.

During their first escape in the stolen car, without pursuit, she joins him for thrills and excitement - her ticket out of the dull anonymity of the town. Without pre-meditation, she slowly and unwittingly slips into a career in crime with him. During the hurried getaway, banjo music by Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs ("Foggy Mountain Breakdown") plays on the soundtrack - theme music that accompanies their escapes. She is sexually excited and ecstatic, smothering him with hugs and kisses in their first love scene, as they careen down a dusty country road. His hold-up of the store is paralleled by her attempted physical attack on him. When they reach a grassy grove of trees in the shade, Clyde begs the seductive and eagerly aggressive female to "slow down" and "cut it out," pushing her away and getting out of the car. He shamefully and restlessly confesses his latent homosexuality, sexual limitations and impotence, and tells her to put aside her romantic intentions:

Clyde: I might as well tell ya right off. I ain't much of a lover boy. But that don't mean nothin' personal about you. I-I-I never saw no percentage in it. Ain't nothin' wrong with me. I don't like boys. (He bumps his head on the driver's side door.)

Bonnie (frustrated and stunned): ...Your advertisin' is just dandy. Folks would never guess you don't have a thing to sell. You'd better take me home now. Now don't you touch me!

As she gets out of the passenger side of the car, he follows after her through the front seat and does a pratfall onto the ground, but quickly uprights himself. Diverting her physical arousal, he entices Bonnie into a glamorous life with his own unrealistic, ignorant and childish fantasies of freedom, wealth and fame. He encourages her to think of him as the answer to her dreams - they could make history together:

Clyde: All right. All right. If all you want's a stud service, you get on back to West Dallas and you stay there the rest of your life. You're worth more than that, a lot more than that and you know it and that's why you're comin' along with me. You could find a lover boy on every damn corner in town. It don't make a damn to them whether you're waitin' on tables or pickin' cotton, but it does make a damn to me!

Bonnie: Why?

Clyde: Why? What's you mean, 'Why?' Because you're different, that's why. You know, you're like me. You want different things. You've got somethin' better than bein' a waitress. You and me travelin' together, we could cut a path clean across this state and Kansas and Missouri and Oklahoma and everybody'd know about it. You listen to me, Miss Bonnie Parker. You listen to me. Now how would you like to go walkin' into the dining room of the Adolphus Hotel in Dallas wearin' a nice silk dress and have everybody waitin' on you? Would you like that? That seem like a lot to ask? That ain't enough for you. You've got a right to that.

He claims that the "minute" he saw her, he had figured out all that he had just told her, and then compliments her: "Because you may be the best damn girl in Texas." He takes her to a restaurant and sizes her up. Clyde instinctively appeals to her wanderlust to leave the dead-end cafe waitress job she has and join him for adventure and a career in crime, when he took her to a restaurant and sized her up:

Clyde: You were born somewhere around East Texas, right?...Come from a big ol' family.... You went to school, of course, but you didn't take to it much, because you was a lot smarter than everybody else, so you just up and quit one day. Now, when you was 16, 17, there was a guy who worked in a, in a ...right, cement plant, and you, you liked him, because he thought you were just as nice as you could be. And you almost married that guy, but then you thought no. You didn't think you would. So then you got you your job in a cafe. And now you wake up every mornin' and you hate it. You just hate it. You get on down there and you put on your white uniform...

Bonnie. Pink, it's pink.

Clyde: And them truckdrivers come in there to eat your greasy burgers and they kid ya, and you kid 'em back. But they're stupid and dumb boys with the big ol' tattooes on 'em, and you don't like it. And they ask ya on dates, and sometimes you go but you mostly don't because all they're ever tryin' to do is get in your pants whether you want 'em to or not. So you go on home and you sit in your room and you think, 'Now when and how am I ever gonna get away from this?' And now you know.

After stealing a sporty convertible coupe, they hide out that night from the law in a deserted, bank-foreclosed farmhouse, where Bonnie sleeps on automobile seats placed on the floor: "These accommodations ain't particularly deluxe." When she awakens in the morning, she is initially frightened, but Clyde's appearance (on the other side of a broken window) reassures her.

While demonstrating his accurate aim during target practice, he shoots bottles off a wooden fence above a sign reading "Property of MIDLOTHIAN CITIZENS BANK - TRESPASSERS WILL BE PROSECUTED." He immodestly tells Bonnie: "I ain't good. I'm the best." Then, in the sunlight he gives her his gun and offers her to try a few shots, using an old rubber-tire swing as the target, while wind blows ominously through the bushes [a foreshadowing of the film's final scene]. The gunshots during her training session attract the attention of the bank-displaced, evicted farmer Otis Harris and his family (resembling the Joads from The Grapes of Wrath (1940), Penn's homage to John Ford's classic film) who are just driving by for a "last look" at their repossessed farm. With a show of sympathy for the farmer's futile plight ("That's a pitiful shame"), Clyde puts holes through the bank's sign. Then as a symbolic gesture, he lets the farmer and his Negro hired hand/sharecropper Davis shoot more bullets into the abandoned building and the panes of its windows. Ironically, the farmer's young child cowers in terror in his mother's arms at the sound of all the gunfire.

Clyde boastfully (but shyly) introduces them with a disarming smile, accentuating the bond they share with the country folk - while anticipating (almost as an afterthought) the course that they are committed to pursue - bank robbery:

This here's Miss Bonnie Parker. I'm Clyde Barrow...We rob banks.

The farmer turns - with an ambiguous and stoic look on his face - and stares back at them.