Psycho (1960) (original) (raw)

Background

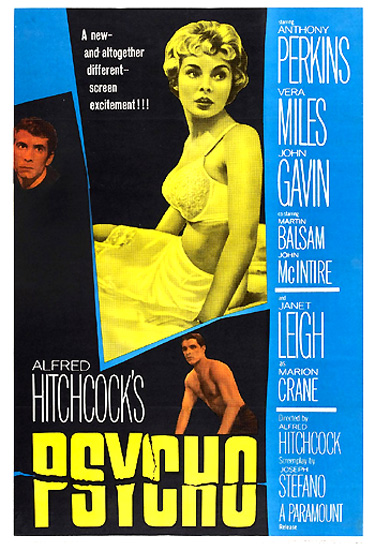

Alfred Hitchcock's powerful, complex psychological thriller, Psycho (1960) is the "mother" of all modern horror suspense films - it single-handedly ushered in an era of inferior screen 'slashers' with blood-letting and graphic, shocking killings (e.g., Peeping Tom (1960, UK), Homicidal (1961), The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), Halloween (1978), Motel Hell (1980), and De Palma's Dressed to Kill (1980) - with another transvestite killer and shower scene). While this was Hitchcock's first real horror film, he was mistakenly labeled as a horror film director ever since. It was advertised as:

Alfred Hitchcock's powerful, complex psychological thriller, Psycho (1960) is the "mother" of all modern horror suspense films - it single-handedly ushered in an era of inferior screen 'slashers' with blood-letting and graphic, shocking killings (e.g., Peeping Tom (1960, UK), Homicidal (1961), The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), Halloween (1978), Motel Hell (1980), and De Palma's Dressed to Kill (1980) - with another transvestite killer and shower scene). While this was Hitchcock's first real horror film, he was mistakenly labeled as a horror film director ever since. It was advertised as:

"A new - and altogether different - screen excitement!!!"

The nightmarish, disturbing film's themes of corruptibility, confused identities, voyeurism, human vulnerabilities and victimization, the deadly effects of money, Oedipal murder, and dark past histories are realistically revealed. Its themes were revealed through repeated uses of motifs, such as birds, eyes, hands, and mirrors.

The low-budget ($800,000), brilliantly-edited, stark black and white film came after Hitchcock's earlier glossy Technicolor hits Vertigo (1958) and North by Northwest (1959), and would have been more suited for as an extended episode for his own b/w TV series Alfred Hitchcock Presents. In fact, the film crew was from the TV show, including cinematographer John L. Russell.

The master of suspense skillfully manipulates and guides the audience into identifying with the main character, luckless victim Marion (a Phoenix real-estate secretary), and then with that character's murderer - a crazy and timid taxidermist named Norman (a brilliant typecasting performance by Anthony Perkins). Hitchcock's techniques voyeuristically implicate the audience with the universal, dark evil forces and secrets present in the film.

Psycho also broke all film conventions by displaying its leading female protagonist having a lunchtime affair in her sexy white undergarments in the first scene; also by photographing a toilet bowl - and flush - in a bathroom (a first in an American film), and killing off its major 'star' Janet Leigh a third of the way into the film (a monumental first that was later copied in Scream (1996) with Drew Barrymore). Her murder occurred (in a shocking, brilliantly-edited shower murder scene accompanied by screeching violins. The 90-odd shot shower scene was meticulously storyboarded by Saul Bass, but directed by Hitchcock himself.

[Note: A satirical parody of scenes from various Hitchcock films, including some from Psycho, were included in Mel Brooks' comedy High Anxiety (1977). The shower scene itself has been referenced, spoofed and parodied in numerous films, including Brian De Palma's The Phantom of the Paradise (1974) and Dressed to Kill (1980), Squirm (1976), Victor Zimmerman's low-budget Fade to Black (1980), Tobe Hooper's The Funhouse (1981), John De Bello's Killer Tomatoes Strike Back! (1990), Martin Walz' The Killer Condom (1997, Ger.), Wes Craven's Scream 2 (1997), Scott Spiegel's From Dusk Till Dawn 2: Texas Blood Money (1999), and the animated Looney Tunes: Back in Action (2003), in which Bugs acts out with the film's black-and-white footage and a can of Hershey's chocolate syrup poured down the drain.]

In this film, Hitchcock's gimmicky device, termed a MacGuffin (the thing or device that motivates the characters, or propels the plot and action), is the stolen $40,000 from the realtor's office. Marion Crane becomes a secondary MacGuffin after her murder.

The film's screenplay by Joseph Stefano was adapted from a novel of the same name by author Robert Bloch. Remarkably, Bloch's 1959 novel was based on legendary real-life, Plainfield, Wisconsin psychotic serial killer Edward Gein, whose murderous character also inspired the mother-obsessed farmer in Deranged (1974), the Leatherface character in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), and serial killer Jame Gumb ("Buffalo Bill") in The Silence of the Lambs (1991).

[Note: Bloch became a major horror screenwriter during the 60s decade and beyond, responsible for such suspenseful horror films and chillers as The Cabinet of Caligari (1962) - an update of the 1919 classic, Strait Jacket (1964), The Night Walker (1964), The Skull (1965), The Psychopath (1966), The Deadly Bees (1967), The Torture Garden (1967), The House That Dripped Blood (1971), Asylum (1972), the short feature Mannikin (1977), and The Amazing Captain Nemo (1977).]

Like many of Hitchcock's films, Psycho is so very layered and complex that multiple viewings are necessary to capture all of its subtlety. Symbolic imagery involving stuffed birds and reflecting mirrors are ever-present. Although it's one of the most frightening films ever made, it has all the elements of very dark, black comedy. This film wasn't clearly understood by its critics when released. Hitchcock admitted that Henri-Georges Clouzot's influential thriller Les Diaboliques (1955, Fr.) inspired his film.

This taut masterpiece was followed by three feature film sequels (none directed by Hitchcock) of lesser quality and other imitations or TV films:

| Title | Director | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| _Psycho (1960)_Not rated until 1968, when an early version of the MPAA ratings system rated it M, for mature audiences only; a 1984 reissue re-rated the film R | Alfred Hitchcock | Anthony Perkins as Norman Bates |

| _Psycho II (1983)_Note: This was a record interval - 23 years between a 'I' and 'II' picture. | Richard Franklin | Anthony Perkins as Norman, released from a mental hospital after 22 years; Marion's sister Lila Loomis (again Vera Miles) protests his release |

| Psycho III (1986) | Anthony Perkins, in his directorial debut | Anthony Perkins as Norman, 25 years later |

| Bates Motel (1987) | Richard Rothstein | TV pilot film, with Bud Cort as Bates Motel manager |

| Psycho IV: The Beginning (1990) | Mick Garris | Made for cable-TV film, with Anthony Perkins as Norman, Henry Thomas as a young Norman, and Olivia Hussey as Norma Bates |

| Psycho (1998) | Gus Van Sant | An almost 'scene-by-scene' (actually 'shot-by-shot') remake (or replication) of the original classic, that only generated interest for the original film |

| Bates Motel (2013-2017). | A&E's prequel series. with Vera Farmiga as Norma Louise Bates, and Freddie Highmore as Norman Bates. |

The film's four Academy Award nominations failed to win Oscars: Best Supporting Actress (Janet Leigh with her sole career nomination), Best Director (Alfred Hitchcock with the last of his five losing nominations), Best B/W Cinematography, and Best B/W Art Direction/Set Decoration. Bernard Herrmann's famous, frightening and memorable score with shrieking, harpie-like piercing violins was un-nominated.

When the film was originally aired in theaters in mid-1960, Hitchcock insisted in a publicity gimmick (a la P.T. Barnum) that no one would be seated after the film had started - the decree was enforced by uniformed Pinkerton guards. Audiences assumed that something horrible would happen in the first few minutes. Violence is present for about two minutes total in only two shocking, grisly murder scenes, the first about a third of the way through, and the second when a Phoenix detective named Arbogast (Martin Balsam) is stabbed at the top of a flight of stairs and topples backwards down the staircase. The remainder of the horror and suspense is created in the mind of the audience, although the tale does include such taboo topics as transvestism, implied incest, and hints of necrophilia.

Plot Synopsis

The bleak, monochrome film is made more effective by Bernard Herrmann's sparse, but driving, recognizable score, first played under the frantic credits (by industry pioneer Saul Bass) - shown with abstract, gray horizontal and vertical lines that streak back and forth, violently splitting apart the screens and causing them to disappear. The frenetic lines appear as prison bars or vertical city buildings. [These criss-crossing patterns, like mirror-images, are correlated to the split, schizophrenic personality of a major protagonist.]

The film opens with the aerial-view camera sweeping left to right along the urban skyline of "PHOENIX, ARIZONA" where some new construction is in progress. [The numerous references to birds in the film begins here, with the city of 'Phoenix'.] The specific date and time are emphasized in titles in the middle of the screen:

FRIDAY, DECEMBER THE ELEVENTH TWO FORTY-THREE P.M

The shot pans across many skyscraper buildings, and after a series of numerous dissolves, randomly chooses to descend and penetrate deeper into one of many windows in a cheaper, high-rise hotel building - the window's venetian blinds narrowly conceal the dingy interior. There, the camera pauses at the half-open window - and then voyeuristically intrudes into the foreground darkness of the drab room. The camera takes a moment to adjust to the black interior - and then pans to the right where a post-coital, semi-nude couple have just completed a seedy, lunch-time tryst. Attractive, single 30-ish secretary, Marion (spelled not with an A but an O - signifying emptiness) Crane (Janet Leigh), wearing only a prominent white bra and slip and reclining back on a double bed, is with her shirtless lover/fiancee Sam Loomis (John Gavin) who stands over her. In the background is a bathroom (the first of three bedrooms with bathrooms in the background).

Sam speaks the first line of dialogue, referring to the uneaten lunch food on the stand - on many levels, she has lost her appetite for their ungratifying relationship and mutual poverty. As he kisses her and they embrace on the bed, they discuss their "cheap" relationship and impoverishment, and their many unresolved issues:

Sam: You never did eat your lunch, did you?

Marion: I'd better get back to the office. These extended lunch hours give my boss excess acid.

Sam: Why don't you call your boss and tell him you're taking the rest of the afternoon off? (It's) Friday anyway - and hot.

Marion: What do I do with my free afternoon? Walk you to the airport?

Sam: Well, you could laze around here a while longer.

Marion (foreshadowing a future hotel visit): Hmm. Checking out time is 3 pm. Hotels of this sort aren't interested in you when you come in, but when your time is up. Oh Sam, I hate having to be with you in a place like this.

Sam: I've heard of married couples who deliberately spend an occasional night in a cheap hotel.

Marion: When you're married, you can do a lot of things deliberately.

Sam: You sure talk like a girl who's been married.

Marion: Sam, this is the last time.

Sam: For what?

Marion: For this, meeting you in secret so we can be secretive. You come down here on business trips. We steal lunch hours. I wish you wouldn't even come.

Sam: All right, what do we do instead? Write each other lurid love letters?

It's a hot, Friday afternoon [although December, it undoubtedly looks like a summer day] and they are obviously in the midst of a "secretive" affair in Room No. 514. She loves Sam but they can only furtively see each other during his business trips. Sam has flown in from a small town in California to see Marion - and "steal lunch hours." As she rises to dress and cover up her ample breasts, they discuss further difficulties in their fitful relationship (characterized as more sexual than intimate). Sam secretly enjoys the illicitness of their sleazy, "lurid" affair and suggests seeing her the next week - and even assents to having "lunch - in public."

It's a hot, Friday afternoon [although December, it undoubtedly looks like a summer day] and they are obviously in the midst of a "secretive" affair in Room No. 514. She loves Sam but they can only furtively see each other during his business trips. Sam has flown in from a small town in California to see Marion - and "steal lunch hours." As she rises to dress and cover up her ample breasts, they discuss further difficulties in their fitful relationship (characterized as more sexual than intimate). Sam secretly enjoys the illicitness of their sleazy, "lurid" affair and suggests seeing her the next week - and even assents to having "lunch - in public."

In a semi-ultimatum to Sam, Marion tells him that "this is the last time" - she will deny him further sexual couplings in "secretive" meetings. She expresses her frustration about their private love trysts and her real desire for marriage - she wants chastity, respectability, and public meetings in the place she shares with her sister (where a framed picture of her dead "Mother" morally disapproves, presides, and judges them). [Of course, there's another morally-disapproving, judgmental 'dead Mother' in the film, but that comes later. One unanswered question in the film: Did Marion spend years nursing her invalid mother - selfless dedication that contributed to her fate as an old maid?] He agrees to see her under the new terms of 'respectability,' although he reminds her how "a lot of sweating out," "patience," and "hard work" would be prerequisites in a respectable relationship [Marion's sister later tellingly asserts: "Patience doesn't run in my family"]:

Marion: Oh, we can see each other. We can even have dinner, but respectably. In my house, with my mother's picture on the mantel, and my sister helping me broil a big steak for three.

Sam: And after the steak, do we send sister to the movies, turn Momma's picture to the wall?

Marion: Sam!

Sam: (begrudgingly) All right. Marion, whenever it's possible I want to see you and under any circumstances, even respectability.

Marion: You make respectability sound disrespectful.

Sam: Oh no, I'm all for it. But it requires patience, temperance, with a lot of sweating out. Otherwise though, it's just hard work. But if I could see you and touch you, you know, simply as this, I won't mind. (He nibbles at her neck.)

Sam, a small-town (Fairvale, California) hardware store proprietor, is also frustrated and self-pitying because of his money worries - he is a financial martyr, burdened by his father's debts and the alimony he must pay to his ex-wife. She proposes marriage directly (she is still a spinster and stuck in the same job after ten years) - and poignantly describes her willingness to share a life of cash-strapped hardship with him. But annoyingly, he balks at the thought, refusing because he doesn't want her to live in poverty and because he believes he must first pay off his debts over the next couple years. She threatens to leave him and thinks she may find "somebody available" to take his place and end her fears of being a fallen woman:

Sam: I'm tired of sweating for people who aren't there. I sweat to pay off my father's debts and he's in his grave. (Sam has walked in front of a fan with spinning blades.) I sweat to pay my ex-wife's alimony and she's living on the other side of the world somewhere.

Marion: I pay too. They also pay who meet in hotel rooms. [This line evokes the famous last line of Milton's sonnet, On His Blindness: "They also serve who only stand and wait."]

Sam: A couple years and my debts will be paid off. If she remarries, the alimony stops.

Marion: I haven't even been married once yet.

Sam: Yeah, but when you do, you'll swing.

Marion: Oh Sam, let's get married! (They kiss and embrace.)

Sam: Yeah. And live with me in a storeroom behind a hardware store in Fairvale? We'll have lots of laughs. I'll tell you what. When I send my ex-wife her alimony, you can lick the stamps.

Marion: I'll lick the stamps.

Sam: Marion, you want to cut this off, go out and find yourself somebody available?

Marion: I'm thinking of it.

Sam: How could you even think a thing like that?

Unhappy and unfulfilled in her unsanctified relationship, Marion rejects his idea to take the afternoon off and rushes back to her storefront real estate office - she is anxious about being late.

[Director Hitchcock, wearing a ten-gallon hat, makes his cameo appearance on the Phoenix sidewalk facing away from the window of the realty office.] She is relieved that her boss Mr. George Lowery (Vaughn Taylor) is not back from lunch, but she suffers from a headache (brought on by her perennial problems with Sam). [Behind her in the office is a framed picture of a barren, desert scene]:

Headaches are like resolutions. You forget them as soon as they stop hurting.

She listens to her recently-married co-worker Caroline (Patricia Hitchcock, Hitchcock's real-life daughter) chatter about her interfering, nagging mother, who had suggested that her doctor prescribe tranquilizers for her wedding day to protect her (from the anguish of losing her virginity and having sex?) - her mother's nosiness angered her proprietary groom/husband Teddy. [Scenes of frigid winter are displayed behind her.] Caroline offers Marion a tranquilizer rather than an aspirin for her headache.

My mother's doctor gave them to me the day of my wedding. Teddy was furious when he found out I'd taken tranquilizers.

Mirrors are ever-present throughout the film - Marion checks out her appearance and applies lipstick using a small compact mirror from her purse. Mr. Lowery arrives shortly afterwards with an important, wealthy (and inebriated) millionaire - a cowboy-hatted customer named Mr. Tom Cassidy (Frank Albertson). He is an oil-lease man who is sweating from the heat and complaining about the weather: "Wow! It's as hot as fresh milk." The salty oilman suggests that Lowery should "air-condition...up" his employees, because he "can afford it today." Mr. Cassidy has just proudly bought a house on Harris Street for his "sweet little girl" - his 18 year old, soon-to-be-married daughter ("baby"):

Tomorrow's the day my sweet little girl - (He leers over at Marion) - Oh, oh, not you - my daughter, a baby. And tomorrow she stands her sweet self up there and gets married away from me. I want you to take a look at my baby. Eighteen years old, and she never had an unhappy day in any one of those years.

Flirting with Marion, he sits on her desk, and sensing that Marion is unhappy and feeling deprived with his talk of marriage, gloats about his wealth and his easing of life's pains through buy-offs:

You know what I do about unhappiness? I buy it off. Are, uh, are you unhappy?

Marion answers that she isn't "inordinately" unhappy - although she is uncomfortably reminded of her unmarried status and other deprivations. Then, the vulgar client takes out the $40,000 in cold, hard cash for the house purchase for his "respectable" married daughter as a wedding present, and boastfully waves and flops it around in front of his audience. He domineeringly explains how virile the money makes him:

Now, that's, that's not buying happiness. That's just buying off unhappiness. I never carry more than I can afford to lose.

He tosses the money on Marion's desk, but the money is not for her - but for Cassidy's daughter's wedding dowry (although she is challenged and tempted by the money earmarked for a bride's house - she feels more entitled to it than the pampered daughter). It is an awkward, discomfiting sight for Marion who has just left her impecunious lover/partner whom she is unable to marry for lack of money. Caroline is astonished by Cassidy's brash proposition: "I declare!" Cassidy even brags about how he doesn't rightfully 'declare' his illicitly-obtained money to the government - an obvious illegality: "I don't. That's how I get to keep it."

Lowery is worried about so much cash out in the open: "A cash transaction of this size is most irregular," but Cassidy assures him: "Aw, so what. It's my private money. Now it's yours." [His transference of the 'dirty' private funds to Lowery suggests that Marion's boss may keep the cash transaction undeclared.] The loud-mouthed Cassidy embarrasses the real estate boss by exposing the presence of something else hidden away and unrevealed - a bottle in the desk in his office. He persuades Lowery to take him into the inner air-conditioned office for a drink. Lowery instructs Marion to put the large amount of cash in a bank's safe deposit box over the weekend: "I don't even want it in the office over the weekend. Put it in the safe deposit box in the bank."

Caroline is jealous that Cassidy flirted with her colleague [Her 'respectable' marriage must be somewhat desperate and unfulfilling.]:

He was flirting with you. I guess he must have noticed my wedding ring.

Both women touch and handle the naughty, filthy money, and then Marion puts it into an envelope, wraps it up and sticks it in her purse. She is granted permission to go straight home after the bank deposit because of her headache. Although she expects to be "in bed" all weekend, Cassidy thinks she needs an escape and propositions her with an invitation:

What you need is a weekend in Las Vegas, the playground of the world!

As she leaves, Marion refuses tranquilizers a second time from her co-worker: "You can't buy off unhappiness with pills." [But obviously, can't her unhappiness be bought off with money?] As she leaves the office, her shadow follows after her.

In the next scene, Marion's shadow precedes her. In a moment of weakness and impulse, she has been tempted to bring the money home to her small bedroom instead of to the bank. (Her sister is away for the weekend in Tucson to "do some buying.") Again in partial undress wearing only a black bra and slip [after the theft, her underclothes turn black - signifying her darkness], Marion repeatedly and apprehensively eyes the money in a fat envelope lying on the bed (where she told Lowery and Cassidy she would spend the weekend). The camera zooms in and cuts back and forth to the envelope more than once. Next to it is her packed suitcase, ready for a trip. [Behind her in this second bedroom in the film is another bathroom - this one with the shower head particularly noticeable. Also, more mirrors and windows and pictures looking down from the wall - two of her as a baby, another of her deceased parents. She has redirected the money intended by Cassidy for his "baby" to her own maternal instincts - her wish to be married to Sam, have respectable sex and raise a family.] She stares long and hard at herself in the dresser mirror. Although she appears casually indifferent and secure in the presence of the money, she nervously finishes packing and closes her full suitcase.

In the next scene, Marion's shadow precedes her. In a moment of weakness and impulse, she has been tempted to bring the money home to her small bedroom instead of to the bank. (Her sister is away for the weekend in Tucson to "do some buying.") Again in partial undress wearing only a black bra and slip [after the theft, her underclothes turn black - signifying her darkness], Marion repeatedly and apprehensively eyes the money in a fat envelope lying on the bed (where she told Lowery and Cassidy she would spend the weekend). The camera zooms in and cuts back and forth to the envelope more than once. Next to it is her packed suitcase, ready for a trip. [Behind her in this second bedroom in the film is another bathroom - this one with the shower head particularly noticeable. Also, more mirrors and windows and pictures looking down from the wall - two of her as a baby, another of her deceased parents. She has redirected the money intended by Cassidy for his "baby" to her own maternal instincts - her wish to be married to Sam, have respectable sex and raise a family.] She stares long and hard at herself in the dresser mirror. Although she appears casually indifferent and secure in the presence of the money, she nervously finishes packing and closes her full suitcase.

She sits down on the bed, stares with desire at the money, and tries to stop herself from doing something she knows is shameful and wrong - something that is not "respectable." But she can't control her sinful, obsessive-compulsive behavior. Because her suitcase is already full and shut, she stuffs the envelope in her purse (with other important papers) and then leaves.

While driving out of Phoenix toward Fairvale, California in her black car, Marion stares straight ahead and trance-like while imagining that she is on her way to elope with Sam with the large sum of cash with which to finance her elopement and marriage. She hears a conversation with a startled Sam who is surprised to see her in Fairvale - with pilfered money for their salvation. His startled, echoing voice speaks in her head. With an uneasy reaction to her appearance, he would undoubtedly reject her solution to their problem:

Marion, what in the world, what are you doing up here? Of course I'm glad to see you. I always am. What is it, Marion?

Their conversation is cut short and interrupted. Significantly, she cannot finish talking with him.

While waiting at a stoplight, her boss (and Cassidy) pass by in the cross-walk in front of her. He at first smiles and nods when recognizing her, and leaves the frame of the windshield. Likewise, she smiles - nervously. But then he stops, turns and furrows his brow at her. Mr. Lowery is puzzled and concerned to see her in her car when she was supposed to be home sick. Likewise, her face turns frozen after realizing that she has been caught. Bernard Herrmann's jarring music begins to play, slashing at her. She pulls away, gulps hard, and looks back - her conscience already gnawing away.

While waiting at a stoplight, her boss (and Cassidy) pass by in the cross-walk in front of her. He at first smiles and nods when recognizing her, and leaves the frame of the windshield. Likewise, she smiles - nervously. But then he stops, turns and furrows his brow at her. Mr. Lowery is puzzled and concerned to see her in her car when she was supposed to be home sick. Likewise, her face turns frozen after realizing that she has been caught. Bernard Herrmann's jarring music begins to play, slashing at her. She pulls away, gulps hard, and looks back - her conscience already gnawing away.

Unnerved but still drifting along irrationally, Marion drives her dark-toned car toward Fairvale from Phoenix and it turns to dusk and nighttime. She repeatedly looks into her rear-view mirror - symbolically checking out her own inner thoughts. She blinks her tired eyes and tries to avoid the glare of headlights of oncoming cars - spotlighting her crime.