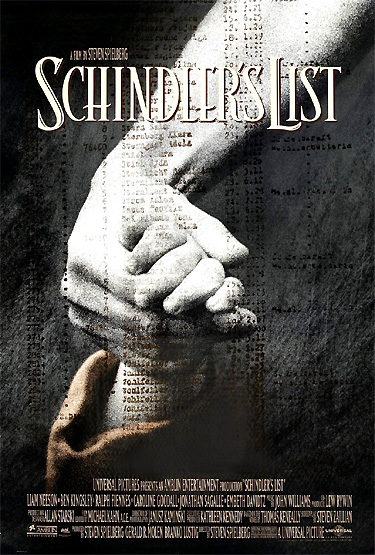

Schindler's List (1993) (original) (raw)

Background

Schindler's List (1993) is Steven Spielberg's unexpected award-winning masterpiece - a profoundly shocking, unsparing, fact-based, three-hour long epic of the nightmarish Holocaust.

Schindler's List (1993) is Steven Spielberg's unexpected award-winning masterpiece - a profoundly shocking, unsparing, fact-based, three-hour long epic of the nightmarish Holocaust.

Its documentary authenticity vividly re-creates a dark, frightening period during World War II, when Jews in Nazi-occupied Krakow were first dispossessed of their businesses and homes, then placed in ghettos and forced labor camps in Plaszow, and finally resettled in concentration camps for execution. The violence and brutality of their treatment in a series of matter-of-fact (and horrific) incidents is indelibly and brilliantly orchestrated.

Except for the bookends (its opening and closing scenes) and two other brief shots (the little girl in a red coat and candles burning with orange flames), the entire film in-between is shot in crisp black and white. The film is marvelous for the way in which it crafts its story without contrived, manipulative Hollywood-ish flourishes (often typical of other Spielberg films) - it is also skillfully rendered with overlapping dialogue, parallel editing, sharp and bold characterizations, contrasting compositions of the two main characters (Schindler and Goeth), cinematographic beauty detailing shadows and light with film-noirish tones, jerky hand-held cameras (cinema verite), a beautifully selected and composed musical score (including Itzhak Perlman's violin), and gripping performances.

The screenplay by Steven Zaillian was adapted from Thomas Keneally's 1982 biographic novel (Schindler's Ark), constructed by interviews with 50 Schindler survivors found in many nations, and other wartime associates of the title character, as well as other written testimonies and sources. Oskar Schindler was an enterprising, womanizing Nazi Sudeten-German industrialist/opportunist and war profiteer, who first exploited the cheap labor of Jewish/Polish workers in a successful enamelware factory (Deutsche Emailwaren Fabrik or D.E.F.), and eventually rescued more than one thousand of them from certain extinction in labor/death camps.

Before the film was made, Spielberg had offered Holocaust survivor and director Roman Polanski the job of making the film, but Polanski declined. Since then, ten years later, Polanski made his own honored Holocaust film, the Best Director-winning The Pianist (2002). Stanley Kubrick abandoned his own plans to make a similar film in the planning stages, called "The Aryan Papers" - based on the Louis Begley novel Wartime Lies. [Note: Italian-American Catholic Martin Scorsese was originally slated to direct the film, but turned down the chance - claiming the film needed a director of Jewish descent - before turning it over to Spielberg.]

The unanimously-praised film with a modest budget of $23 million deservedly won seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director (the first for Spielberg), Best Cinematography (Janusz Kaminski), Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Original Score (John Williams), Best Editing (Michael Kahn), and Best Art Direction. It also won nominations for two of its male leads: Best Actor (Liam Neeson) and Best Supporting Actor (Ralph Fiennes), Best Costume Design, Best Sound, and Best Makeup. Other organizations including the British Academy Awards, the New York Film Critics Circle, and the Golden Globes, likewise honored the film. It was the first black/white film since The Apartment (1960) to win the Best Picture Academy Award, and the most commercially-successful B/W film in cinematic history.

Plot Synopsis

The film opens, with one of its few color scenes, with a closeup of a hand lighting votive candles with a match in a pre-war Polish Jewish family's home on a Friday night Sabbath. After the singing of a prayer/incantation, the family vanishes from view. The two Shabbat candles burn down as they sit in solitary on a table. In a closeup shot, a reddish-glowing flame extinguishes itself, sending a small pillar of wispy smoke upward from the candle - the smoke in the color scene dissolves into the grayish smoke (the film becomes monochrome here) that bellows from a steam locomotive of a transport train pulling into a station in Krakow, Poland, just as the juggernaut against the Jews begins in the fall of 1939. World War II has dawned in Europe:

September 1939, the German forces defeated the Polish Army in two weeks. Jews were ordered to register all family members and relocate to major cities. More than 10,000 Jews from the countryside arrive in Krakow daily.

One folding table with a wooden top is set up in rural Poland on a small train platform with a clipboard, paper lists-forms, an inkpad, blotter, stapler, stamp, and ink bottle to register a small rural Jewish family. The first spoken word of dialogue in the film is "Name?" [Names and lists are two of the film's major visual motifs.] The scene is repeated and multiplied with many more tables, government officials, and bewildered refugees as more and more Jews arrive in the big city of Krakow to be registered. Large, magnified typewritten letters rap out the Jewish names: Hudes Isak, Feber, Bauman, Klein, Chaim, Neuman, Samuel, Salomon, Horn, Steiner.

Melancholy classical music from a radio plays before the scene switches to a Krakow hotel room. [The piece is the Hungarian love song Gloomy Sunday, originally written around 1933 by Rezso Seress, a Hungarian pianist.] A mysterious, unknown man pours himself a drink, lays out ties on various silk suits on his bed, chooses a fancy cufflink, knots his tie, dresses himself in impeccable fashion with a folded handkerchief in the pocket of his double-breasted suit, counts out lots of money from his bureau for the evening, and pins, in close-up, a gold, Nazi Party button (with swastika or Hakenkreuz) on his lapel.

The camera follows from behind the slickly-dressed gentleman as he enters a swanky nightclub in the Nazi-occupied city of Krakow and slips bank notes, the first of many bribes, to Martin, the maitre d' (the film's co-producer Branko Lustig, an Auschwitz survivor) for placement at a fancy table. The handsome, majestic, lavish-spending, slickly-dressed, man-about-town playboy with an eye for the ladies is the authoritative, aristocratic-looking Oskar Schindler (Liam Neeson), not yet identified by name. With sharp observational skills, he watches as SS Officers at another table are photographed - he sizes up the power elite in his high-stakes gamble to cultivate their friendship. He notices a conspicuously-empty table in the front of the club with a "RESERVE" card on it. With a hand held up with a wad of bills, the bon-vivant buys a round of premium drinks for the top brass (and their female companion) which soon occupy the front-and-center table, and persuades them with intimidating charm to join him at his table for more drinks. The group of people surrounding Schindler swells to include many more SS officers paired up with cabaret entertainers/dancers - the gracious host purchases endless plates of food, caviar, and French wines for the rowdy guests in his party. Schindler's self-promotion is successful - the separate tables in the club merge into one. An SS officer stuffs his mouth and brags about 'weathering the storm':

This storm is different. This is not the Romans. This storm is the SS.

Soon, the scheming and manipulative Schindler prominently insinuates himself and becomes the center of the party - he rubs shoulders with everyone in the room to make a name for himself - the first step in his pragmatic business scheme to become a war profiteer and capitalize on the changing political environment. Even a top colonel, Scherner, who is later brought to the RESERVED table, gravitates to him. The maitre d' authoritatively announces the name of the flamboyant man: "That's Oskar Schindler!" Schindler has his pictures taken (with a big camera with garish flashbulb) with all the top brass, the showgirls, and other women. [Later in the ghetto massacre scene, other flashes of light in window frames are the firings of machine-guns.]

More and more Nazis march in the streets of Krakow and slowly erode the freedoms of Jews. One Orthodox Jewish man stands amidst several soldiers while one of them intimidates him by cutting off his payess (curly side locks of hair) with a slice of his bayonet. Schindler, identified by the camera with only his Nazi button-holed pin, walks along the street's sidewalk as he passes a long line of Jewish refugees, each wearing identifying armbands. They are part of the huge influx of rural Jews who arrive every day on SS trains. A truck with a loud-speaker mounted on its cab hood issues another alert or edict - a restrictive announcement during the occupation.

Schindler spirals his way up the staircase into the Judenrat, a virtually-powerless council of Jewish administrators:

The Judenrat

The Jewish Council comprised of 24 elected Jews personally responsible for carrying out the orders of the regime in Krakow, such as drawing up lists for work details, food and housing. A place to lodge complaints.

In the crowded office of the Judenrat filled with desperate people, one dispossessed Jewish woman complains about the intrusion of Nazis into their private lives and the confiscation of property: "They come into our house and tell us we don't live there anymore. It now belongs to a certain SS officer...Aren't you supposed to be able to help?" At the front of the line, Schindler's voice distinctively addresses the administrators: "Itzhak Stern. I'm looking for Itzhak Stern." A bespectacled, timid man in the back corner of the office finally manages to acknowledge his identity as Itzhak Stern (Ben Kingsley), a gifted accountant.

In another office with Stern, the suave enterpreneur Schindler [a relatively-poor Sudeten German who failed as an entrepreneur before the war] discusses his capitalistic business arrangement and plan to take over a former, confiscated pots and pans company to manufacture mess kits and cookware for the troops at the front, and to make Stern his accountant. [Smooth and opportunistic, Schindler is 'on the make' with Jews as well as with the Nazis.] Schindler describes his strong suit in creating panache or "the presentation," while Stern's talent will be to recruit Jewish investors for capital, to provide 'free' Jewish workers (as cheap labor) from the population, and to manage the business and financial side of the operation:

Schindler: There's a company you did the books for on Lipowa Street, made what - pots and pans?

Stern: By law, I have to tell you, sir, I'm a Jew.

Schindler: Well, I'm a German, so there we are. (Schindler pours a shot of cognac into the cap of his flask and offers it to Stern - who declines.) A good company you think?

Stern: Modestly successful.

Schindler: I know nothing about enamelware, do you?

Stern: I was just the accountant.

Schindler: Simple engineering, though, wouldn't you think? Change the machines around, whatever you do, you could make other things, couldn't you? Field kits, mess kits, army contracts. Once the war ends, forget it, but for now it's great. You could make a fortune, don't you think?

Stern: I think most people right now have other priorities.

Schindler: Like what?

Stern: I'm sure you'll do just fine once you get the contracts. In fact, the worse things get, the better you will do.

Schindler: Oh, I can get the signatures I need - that's the easy part. Finding the money to buy the company, that's hard.

Stern: You don't have any money?

Schindler: Not that kind of money. You know anybody? Jews, yeah. Investors. You must have contacts in the Jewish business community working here.

Stern: What "community"? Jews can no longer own businesses. That's why this one's in receivership.

Schindler: Ah, but they wouldn't own it. I'd own it. I'd pay them back in product. Pots and pans.

Stern: (non-plussed) Pots and pans.

Schindler: Something they can use. Something they can feel in their hands. They can trade it on the black market, do whatever they want. Everybody's happy. If you want, you could run the company for me.

Stern: Let me understand. They'd put up all the money. I'd do all the work. But what, if you don't mind my asking, would you do?

Schindler: I'd make sure it's known the company's in business. I'd see that it had a certain panache - that's what I'm good at, not the work, not the work. (He spreads his open palms out) - the presentation. (A long pause)

Stern: I'm sure I don't know anybody who'd be interested in this.

Schindler: Well, they should be...Tell them they should be.

A young Polish Jew, Poldak Pfefferberg (Jonathan Sagalle) pauses in front of a shop window display where there is a picture of a human skull with lines indicating the smaller circumference (and lesser intelligence) of the Judaic brain. He discreetly removes his Jewish armband and enters a Catholic cathedral where he genuflects himself with holy water. As a priest performs Mass to parishioners scattered in the pews, a number of Jewish black marketeers use the cathedral as a safe meeting place to cover up their whispered business about the latest commercial deals: "Marks for Zloty at 2.45 to 1," "it's a nice coat - she'll trade it for ration coupons." Suddenly, Schindler (with his prominent Nazi button on his coat) appears next to them, asking: "That's a nice shirt. Nice shirt. Do you know where I can find a nice shirt like that?" Most of the other nervous Jews scatter quickly, but Pfefferberg remains behind to pursue the transaction.

One of Pfefferberg's fellow hustlers, Marcel Goldberg (Mark Ivanir) gives a hollow excuse: "It's illegal to buy or sell anything on the street. We don't do that. We're here to pray," and then leans forward to feign praying. When the others won't chance it, Pfefferberg is left alone to bargain with Schindler for his expensive tastes for black market luxury goods - so he can bribe German officers and further encourage his own business ventures:

Pfefferberg: Do you have any idea how much a shirt like this costs?

Schindler: Nice things cost money.

Pfefferberg: How many?

Schindler: I'm going to need some other things too as things come up...

Pfefferberg: This won't be a problem.

Schindler: ...from time to time.

March 20, 1941

Deadline for Entering the Ghetto Edict 44/91 establishes a closed Jewish district south of the Vistula River. Residency in the walled ghetto is compulsory. All Jews from Krakow and surrounding areas are forced from their homes and required to crowd into an area of only sixteen square blocks.

With the creation of Jewish ghettos by the Nazis, thousands of families carry their belongings or push them in barrows on the forced, mass exodus from rural homes. In the winter snow, they trundle up to more makeshift folding tables to be added to lists, have their cards stamped, and to be assigned to ghetto housing. In an elegant apartment as they are evicted under the watchful eye of the SS, the wealthy Jewish inhabitants, the Nussbaums, gather together framed pictures, silverware, and anything else of value that they can carry with them. They are herded out of the fancy building into the street, to join the throngs of others pushing large carts piled high with furniture toward the segregated ghetto. One Polish girl, one of many neighboring spectators, screams out at the parade with frightening prejudice and revilement: "Goodbye Jews."

With parallel editing, a smug Oskar Schindler is chauffeured to the same fashionable apartment and shown his new dwelling - the Nussbaums' lavish vacated apartment with its fine furnishings, Persian rugs, French doors, and hardwood floors. The dispossessed family is led up a crowded staircase inside a rundown ghetto tenement. They haul their belongings up to their assigned living quarters - while Schindler inspects his new apartment and sprawls himself out on their bed, commenting: "It couldn't be better." The Nussbaum family enters into one of the dingy, unheated, empty apartments - children cry as they look at each other in dismay:

Mrs. Nussbaum: It could be worse.

Mr. Nussbaum: (disbelieving) How? Tell me. How on earth could it possibly be worse?

More families, orthodox Jews, shuffle in by them to find their places in the ghetto.

At the ghetto gate, where the Jews are forced to check in at the folding tables for their housing assignments, Pfefferberg, with his attractive wife Mila (Adi Nitzan), is astonished to see that his Jewish friend Goldberg has sold out - he has somehow made an agreement with the Nazi Gestapo to be granted a position of authority as a ghetto policeman: "I'm a policeman now, could you believe it? That's what's hard to believe...It's a good racket, Poldek. It's the only racket here. Look, maybe I could put in a good word for you with my superiors...Come on, they're not as bad as everyone says. Well, they're worse than everyone says, but it's a lot of money, a lot of money."

Stern arranges to have several wealthy Jewish elders meet with profiteer Schindler in his car parked outside the ghetto gates to discuss investment backing in Schindler's pan-manufacturing factory. The Jewish investors are made to understand that conventional wealth and status no longer have any meaning for them. Their only bargaining power is to accept his harsh terms - he will supply them with some of the production goods - pots and pans - to sell on the black market:

Schindler: For each thousand you invest, I will repay you with (Stern provides the number) two hundred kilos of enamel ware a month, to begin in July and to continue for one year - after which time we're even. That's it. It's very simple.

Investor: Not good enough...

Schindler: Not good enough? Look where you're living. Look where you've been put. 'Not good enough.' A couple of months ago, you'd be right. Not anymore.

Investor: Money's still money.

Schindler: No it is not. That's why we're here. Trade goods, that's the only currency that'll be worth anything in the ghetto. Things have changed, my friend. (slightly irritated) Did I call this meeting? You told Mr. Stern you wanted to speak to me. I'm here. I've made you a fair offer.

Investor: Fair would be a percentage of the company.

Schindler: (laughs) Forget the whole thing. Get out.

Investor: How do we know that you will do what you say?

Schindler: Because I said I would. Do you want a contract? To be upheld by what court? I said what I'll do, that's our contract. (While they think it over, Schindler offers a drink of cognac to Stern - he stares at it and silently declines)

Valises filled with money are passed to Schindler for the purchase of the confiscated enamelware factory. He peers down from behind a wall of windows in the upstairs office - a Jewish technician pushes a button to start the machinery in the debris-strewn plant. Stern has been appointed the factory's accountant and plant manager. To Schindler, it makes good economic sense that he would make more money if Jews were hired as the unpaid work force, because they're obviously cheaper than Poles:

Stern: The standard SS rate for Jewish skilled labor is seven marks a day, five for unskilled and women. This is what you pay the Reich Economic Office, the Jews themselves receive nothing. Poles you pay wages. Generally, they get a little more. Are you listening?...The Jewish worker's salary - you pay it directly to the SS, not to the worker. He gets nothing.

Schindler: But it's less. It's less than what I would pay a Pole...That's the point I'm trying to make. Poles cost more. Why should I hire Poles?

Acting as his middleman, Stern recruits Jews to work in Schindler's enamelware factory located "outside the ghetto so you can barter for extra goods, for eggs, I don't know what you need. With the Polish workers, you can't get a deal. Also, he's asking for ten healthy women for the..." The names of 'non-essential' people (who can't contribute something valuable to the war effort), such as musicians or teachers, are placed on a list and then herded onto trucks bound for unknown destinations - undoubtedly concentration camps or extermination.

With humanistic intentions to save those who have no 'essential' skills, Stern forges documents and provides work certificates to rescue from extermination those who would be considered 'not essential'. In one case, he saves the doomed life of a teacher of history and literature, transforming him into a metal polisher. The teacher's work documents are stamped by a satisfied German clerk, placing him in the category of Blauschein - an 'essential' worker with a "blue stamp" in a war-protected industry.

On Schindler's factory floor, the recruited Jewish workers, including the teacher, are given instruction by a technician on how to use the heavy machinery to manufacture a soup bowl, and dip the cooking utensils into vats of enamel. A sign painter brushes the words "DIREKTOR" on the frosted glass of the door to Schindler's office, as he interviews many young female candidates seated before him for secretarial positions: "Filing, billing, keeping track of my appointments. Shorthand. Typing obviously. How is your typing?" The scene jump-cuts through a succession of girls at the typewriter. Time passes, illustrated by the movement of the painters' ladders around the wall of the room. For comic relief in the film, Schindler show flirtatious interest in the prettier candidates who hunt and peck, but glumly sits back with utter disinterest when the fastest typist (a dour, cigarette-smoking, plump matron) is being tested. One of the sultriest young ladies does a seductively-slow one-finger dance with the typewriter - and with Schindler. Because Schindler can't decide, he hires eighteen of the prettiest, most 'qualified' young ladies as secretaries - and is posed with them by a photographer outside the re-possessed plant in front of the imposing sign for the factory:

D.E.F. DEUTSCHE EMAILWARENFABRIK

In a scene with parallel editing and overlapping, voice-over dialogue, gadabout Schindler entertains - and seduces - SS German officers with rich food, caviar and drink in his apartment. As part of an elaborate confidence game, he provides some of his pretty secretaries to the men, as he reads off a list of black market items (including perishables and cognac) to be acquired (with invested Jewish money) from Poles by Pfefferberg:

Boxed teas are good, coffee, pate, uhm, kilbassa sausage, cheeses, caviar. And of course, who could live without German cigarettes and as many as you can find. And some more fresh fruit - they're real rarities, oranges, lemons, pineapples. I need several boxes of German cigars, the best. And dark and sweetened chocolate, not in the shape of lady fingers...we're going to need lots of cognac, the best - Hennessy. Dom Perignon champagne. Get L'Espadon sardines. And, oh, try to find nylon stockings.

Under a bridge crossing the Vistula River, a man pulls aside a tarpaulin covering boxes of fresh fruit in the bottom of his rowboat and is paid with cash. A bribed doctor opens a medicine cabinet and pushes aside medicines, revealing a hidden compartment behind holding several bottles of Hennessey cognac. Beneath the ties of train tracks, a metal case is pulled from beneath one of the timbers, revealing a case of sardines.

(Schindler's voice-over) It is my distinct pleasure to announce the fully operational status of Deutsche Emailwaren Fabrik - manufacturers of superior enamelware crockery, expressly designed and crafted for military use, utilizing only the most modern equipment. DEF's staff of highly skilled and experienced artisans and journeymen deliver a product of unparalleled quality, enabling me to proffer with absolute confidence and pride, a full line of field and kitchen ware unsurpassable in all respects by my competitors. See attached list and available colors. Anticipating the enclosed bids will meet with your approval. And looking forward to a long and mutually prosperous association. I extend to you, in advance, my sincerest gratitude and very best regards. Oskar Schindler.

Elaborate gift baskets (of liquor, cigarettes, coffee, tea, fresh fruit, and other rare luxury goods) with the accompanying letter from above - are assembled and carried by Schindler's cadre of pretty secretaries through the factory (where novice workers struggle to learn the new craft), and strategically delivered to SS officers (the ones he had earlier been photographed with in the nightclub) to irresistibly stimulate bids and purchase contracts. The ultimate con artist, Schindler bribes and schemes his way toward wealth.

The Direktor strides through his factory, dictating to a parade of his secretaries about production demands and delivery details. As expected, one of the many SS officers, Julian Scherner (Andrzej Seweryn), signs and stamps his approval of a materials contract with D.E. F. To praise his accountant's efforts for reaping profits and to treat him as an equal, Schindler calls the self-effacing Stern to his office to share a drink from his decanter:

Schindler: My father was fond of saying you need three things in life. A good doctor, a forgiving priest, and a clever accountant. The first two, I've never had much use for them. But the third - (he raises his glass to recognize Stern, but the accountant doesn't respond) Just pretend, for Christ's sake. (Stern mechanically raises his glass slightly)

Stern: Is that all?

Schindler: I'm trying to thank you. I'm saying I couldn't have done this without you. The usual thing would be to acknowledge my gratitude. It would also, by the way, be the courteous thing.

Stern: (in a hollow tone) You're welcome. (Schindler finishes both drinks)

Schindler's girlfriend, Victoria Klonowska (Malgoscha Gebel), wearing his silk robe covering her slip, answers the door of his apartment early one morning. She feels embarrassed to see Emilie Schindler (Caroline Goodall), Schindler's estranged wife from back home, standing there. The humiliated mistress of the evening hurriedly leaves, thoroughly self-conscious. With self-deprecating innocence and charm after being caught as an unfaithful adulterer, Schindler flatters his wife: "You look wonderful." That night, they emerge from his apartment building in formal clothes to go to a fancy restaurant. With his reputation for women, the doorman can't quite believe that the woman on Schindler's arm is indeed "Mrs. Schindler." During dinner, Schindler explains that his wealthy accoutrements (car, apartment) are "not a charade" - he has 350 workers on his factory payroll.

Schindler: Three hundred and fifty workers on the factory floor with one purpose...to make money - for me!...They won't soon forget the name Schindler either. I can tell you that. Oskar Schindler, they'll say. Everybody remembers him. He did something extraordinary. He did something no one else did. He came here with nothing, a suitcase, and built a bankrupt company into a major manufactory. And left with a steamer trunk, two steamer trunks, full of money. All the riches of the world...There's no way I could have known this before, but there was always something missing. In every business I tried, I can see now it wasn't me that had failed. Something was missing. Even if I'd known what it was, there's nothing I could have done about it, because you can't create this thing. And it makes all the difference in the world between success and failure.

Emilie: Luck.

Schindler: War.

The next day, after being given no assurance of love or steadfast devotion, Emilie boards a departing train, shakes his hand as it pulls away, and waves goodbye.

In his office above the factory, Schindler is presented with a financial report by Stern. The factory is doing "better this month than last," but next month may be worse if the war ends. Stern asks permission to bring in a grateful machinist, Mr. Lowenstein (Henryk Bista), to personally thank Schindler for giving him a job. The elderly, one armed man with bruises on his face appears in the doorway - Schindler appears long-suffering as he listens perfunctorily to the praise of the man: "The SS beat me up. They would have killed me, but I'm essential to the war effort, thanks to you...I work hard for you...I'll continue to work hard for you...God bless you sir...You're a good man...(To Stern) He saved my life...God bless him...(To Schindler) God bless you." Later, Schindler angrily tells Stern that the 'one-armed,' old, unskilled worker shouldn't have been allowed to work: "What's his use?"

One snowy winter morning, Schindler's workers are marched out of the ghetto gate, under armed guard, to the factory for their work day. A squad of SS troopers halts them and orders them to shovel snow from the street. In flashback, Schindler's SS contact sits behind a desk rationalizing the incident: "Jews shoveling snow. It's got a ritual significance." Lowenstein, proudly proclaiming himself as "an essential worker for Oskar Schindler," is plucked from the group by a few SS, declared "twice as useless" and inefficient, led a short distance away, and shot point-blank in the head. Blood slowly flows from the corpse's head wound, darkening, drenching, and melting the snow. Oskar is maddened by the senseless death and loss of a worker, but he knows that filing a grievance with the Economic Office for compensation (for the "one-armed machinist") wouldn't do any good.

On a train platform, soldiers and clerks with typed lists are supervising the boarding of hundreds of Jews into cattle cars. They are promised: "Leave your luggage on the platform. Clearly label it...Do not bring your baggage with you. It will follow you later." Pfefferberg has summoned Schindler from a love-making session to the station to search for Stern - who has been mistakenly placed on one of the slatted livestock cars bound for liquidation. Boldly and brazenly, Schindler asks for the Gestapo clerk's name who has identified Stern's name on the list and dutifully refuses to release him: "I'm sorry. You can't have him. He's on the list. If he were an essential worker, he would not be on the list."

In a tense scene, he cooly threatens both the clerk and a superior, an SS sergeant, who refuse to release his plant manager, bluffing them into compliance: "I think I can guarantee you you'll both be in Southern Russia before the end of the month. Good day." He walks along the cars - joined by the intimidated clerk and sergeant, urgently calling out Stern's name, as the locomotive begins to move and pick up speed. After Stern is located in one of the cars, Schindler orders that the train is stopped. The brakeman responds, and the wheels screech to a grinding halt. The gate on the door is opened and Stern climbs out in the last-instant rescue. Schindler is instructed by the clerk to sign and initial his name next to Stern's name on the clipboard list: "It makes no difference to us, you understand. This one, that one. It's the inconvenience to the list. It's the paperwork."

The camera tracks backward from the two of them as Stern hurries along to keep up with the long stride of Schindler - he explains and apologizes for his grave error: "I somehow left my work card at home. I tried to explain them it was a mistake, but...I'm sorry, it was stupid." Schindler replies about the concern for his own fate: "What if I got here five minutes later? Then where would I be?" They pass one of the handcarts with the carefully-labeled luggage. The camera leaves them and follows the cart as it is wheeled into a warehouse/garage where the suitcases are piled up. Under SS guard, the clothing is removed and thrown onto one pile. Other large piles hold shoes, metal items, photographs, and wrist watches. Some of the more valuable possessions with gold and silver content (candelabra, Passover platters) are tagged and sorted on shelves. Jewish jewelers sift, sort, weigh, and grade the value of diamonds, pearls, pendants, brooches, and rings. The jeweler reacts when a satchel of extracted human teeth with gold and silver fillings is dumped on his desk.