MargaretFuller (original) (raw)

FLORIN WEBSITE � JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO ASSOCIAZIONE, 1997-2024: MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, SWEET NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, & GEOFFREY CHAUCER || VICTORIAN : WHITE SILENCE: FLORENCE'S 'ENGLISH' CEMETERY || ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING ||WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR || FRANCES TROLLOPE || || HIRAM POWERS || ABOLITION OF SLAVERY || FLORENCE IN SEPIA || CITY AND BOOK CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS I, II, III, IV, V, VI,VII || MEDIATHECA 'FIORETTA MAZZEI' || EDITRICEAUREO ANELLO CATALOGUE || FLORIN WEBSITE || UMILTA WEBSITE || LINGUE/LANGUAGES:ITALIANO,ENGLISH || VITA New: Dante vivo || White Silence

MARGARET FULLER OSSOLI - ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNINGJULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAYI. The Encounter, the Friendship

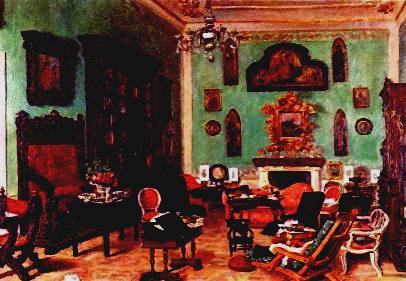

Giorgio Mignaty, 1861

Giorgio Mignaty, 1861

lizabeth Barrett Browning in Casa Guidi, kept carefully cloistered by Robert, her husband, often disapproved of supposedly fallen women visiting Florence, among them Frances Trollope, George Eliot and Margaret Fuller. Margaret was in double jeopardy being not only an unwed mother with a bastard child but also an American, from the hated country of slavery and vulgarity. But in the case of Margaret Elizabeth certainly relented and welcomed this young mother, her child Angelo, so close in age to her own Pennini, and her noble Italian supposed husband - whether he was indeed such, at this time Catholics being unable to marry Protestants. During their Florentine visit the two families were like those Holy Family tableaux the art historian friend Anna Jameson taught John Ruskin to love, the baby Angelo and the baby Pen playing together, just six months difference in age, exactly like John the Baptist and Jesus, iconography that Elizabeth will use in her Bellosguardo scene in Aurora Leigh.

lizabeth Barrett Browning in Casa Guidi, kept carefully cloistered by Robert, her husband, often disapproved of supposedly fallen women visiting Florence, among them Frances Trollope, George Eliot and Margaret Fuller. Margaret was in double jeopardy being not only an unwed mother with a bastard child but also an American, from the hated country of slavery and vulgarity. But in the case of Margaret Elizabeth certainly relented and welcomed this young mother, her child Angelo, so close in age to her own Pennini, and her noble Italian supposed husband - whether he was indeed such, at this time Catholics being unable to marry Protestants. During their Florentine visit the two families were like those Holy Family tableaux the art historian friend Anna Jameson taught John Ruskin to love, the baby Angelo and the baby Pen playing together, just six months difference in age, exactly like John the Baptist and Jesus, iconography that Elizabeth will use in her Bellosguardo scene in Aurora Leigh.

This is how Sophia Peabody Hawthorne described visiting Casa Guidi, 8 June 1857:

This day has been memorable by my seeing Mr and Mrs Browning for the first time. At noon Mr Browning called upon us. His grasp of the hand gives new value to life, revealing so much fervor and sincerity of nature. He invited us most cordially to go at eight and spend the evening. * * * * * and so at eight we went to the illustrious Casa Guidi. We found a little boy in an upper hall, with a servant. I asked him if he were Pennini, and he said 'Yes'. In the dim light he looked like a wiaf of poetry, drifted up into the dark corner, with long, curling, brown hair and buff silk tunic, embroidered with white. He took us through an ante-room, into the drawing-room, and out upon the balcony. In a brighter light he was lovelier still, with brown eyes, fair skin, and a slender, graceful figure. In a moment Mr Browning appeared, and welcomed us cordially. In a church near by, opposite the house, a melodious choir was chanting. The balcony was full of flowers in vases, growing and blooming. In the dark blue fields of space overhead, the stars, flowers of light, were also blossoming, one by one, as evening deepened. The music, the stars, the flowers, Mr Browning and his child, all combined to entrance my wits.

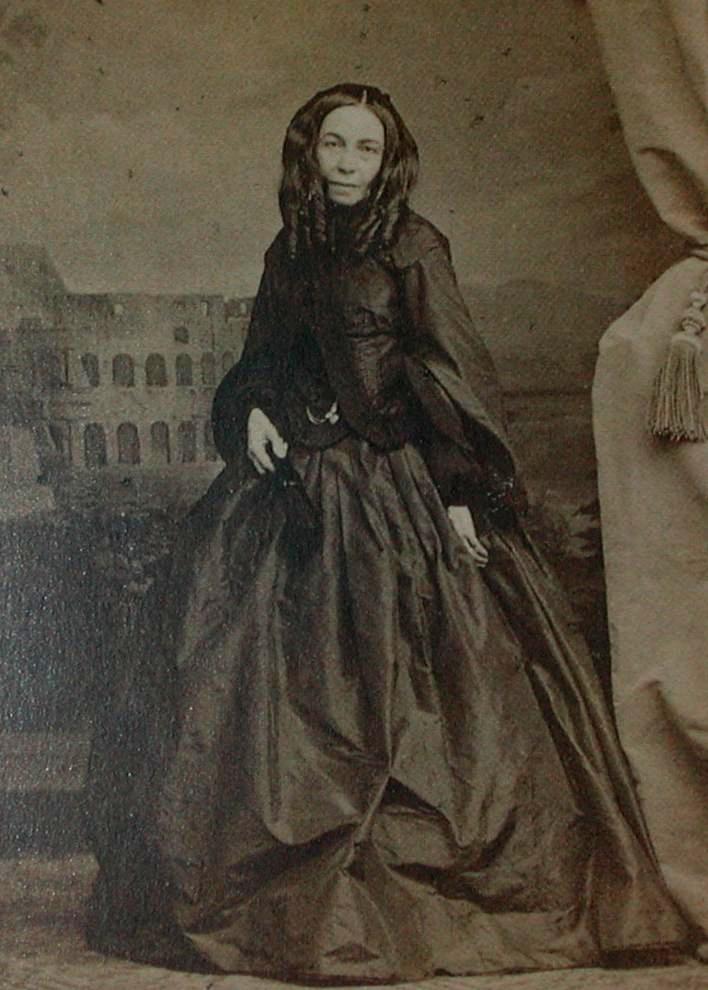

Elizabeth Barrett Browning,

Michele Gordigiani, 1858

Then Mrs Browning came out to us - very small, delicate, dark and expressive. She looked like a spirit. A cloud of hair falls on each side her face in curls, so as partly to veil her features. But out of the veil look sweet, sad eyes, musing and far-seeing and weird. Her fairy fingers seem too airy to hold, and yet their pressure was very firm and strong. The smallest possible amount of substance encloses her soul, and every particle of it is infused with heart and intellect. I was never conscious of so little unredeemed, perishable dust in any human being. I gave her a branch of small pink roses, twelve on the stem, in various stages of bloom, which I had plucked from our terrace vine, and she fastened it in her black-velvet dress with most lovely effect to her whole aspect. Such roses were fit emblems of her.

We soon returned to the drawing-room - a lofty, spacious apartment, hung with gobelin tapestry and pictures, and filled with carved furniture and objects of vert�. Everything harmonized - Poet, Poetess, child, house, the rich air and the starry night. Pennini was an Ariel, flitting about, gentle, tricksy, and intellectual - but it rather disturbed my dream 'of the golden prime of the good Haroun Alraschid' to have a certain Mr and Mrs E[ckley] come in, and then Mr B. and his daughter. Mr B. is always welcome to the eye, with his snowdrift of beard and hair, and handsome face; but he looked too inflexible and hard for that society. The three poets, Mr Browning, Mr B. and Mr Hawthorne, both their heads together in a triangle, and talked a great deal, while Mrs E. told me what an angel Mrs Browning is; and Mr E. talked to Ada, who looked charmingly, in white muslin and blue ribbons - her face a gleam of delight, because she was so glad to be at Casa Guidi. Tea was brought and served on a long, narrow table, placed before a sofa, and Mrs Browning presided, assisted by Mrs E. We all gathered at this table. Pennini handed about the cake, graceful as Ganymede. Mr Browning introduced the subject of spiritism, and there was an animated talk. Mr Browning cannot believe, and Mrs Browning cannot help believing. They kindly expressed regret that they were going to the seaside in a few weeks, since we were to stay in Florence, and hoped to find us here on their return. Mrs Browning wished me to take Una to see her, and Mr Browning exclaimed, 'You must send Pennini to see their boy, Julian - such a fine creature! with eyes kindling - Pennini must see him, and the little Rose, a dearest little thing'. This I record for my children's sake, hereafter. II. Elizabeth Barrett BrowningElizabeth, Kate Field, Lilian Whiting and Jeanette Marks note, came from a slave-owning family in Jamaica, was herself part Black, and precociously studied Greek and Hebrew as a small child amidst the magnificent library of books assembled by her Jamaican-born father, while also longing to be a pageboy to Lord Byron. With the ending of slavery by the British - America would take much longer and with much bloodshed - her father's wealth was greatly reduced. Ill with tuberculosis she was sent from London to Torquay where she wrote poetry with Theodosia Garrow, the quarter East Indian, half Jewish fellow invalid, and where her brother, known as 'Bro' drowned. He was the heir to the family estate of Cinnamon Hill in Jamaica. Elizabeth was shattered with both illness - tuberculosis of the spine - and guilt.She was brought back to London, to Wimpole Street, in a coach with a thousand springs and in a sealed room began to recover. Hengist Horne, Leonard Horner and Thomas Southwood Smith involved her in their work against the employment of children in mines and factories and she wrote 'Cry of the Children', Francis Trollope, who had written 'Jonathan Jefferson Whitlaw' against slavery, wrote 'Michael Armstrong, Factory Boy'. 'Cry of the Children' was read in the House of Lords and effected the passage of legislation protecting working children. She also assisted Hengist Horne with the biographical essays on the New Spirit of the Age, essays which included ones on Robert Browning, Alfred Tennyson, Thomas Southwood Smith, Walter Savage Landor, Frances Trollope and herself.

Her father, fearing a black child in the family, forbade any of his twelve sons and daughters to marry. Her publisher asked her for another poem to fill out the pages of a volume, and she dashed off Lady Geraldine's Courtship, a marvellous poem in which an Earl's daughter proposes marriage to both Alfred Tennyson and Robert Browning, neither of whom had she met. She placed on her bedroom wall the two engravings from New Spirit of the Age of Tennyson and Browning, her brothers turning them face to the wall when a certain visitor came to see her. For Robert read the poem on returning from Europe and immediately dashed off his first love letter to her. Against her father's knowledge at forty she carried out this clandestine courtship with the fellow poet, Robert Browning, eloping with him, following passionate exchanged letters and hidden love sonnets, journeying together with her maid, Lily Wilson, and her dog Flush, first to Paris, then to Pisa, then to Florence. She lived here for fifteen years, writing Casa Guidi Windows to support the Risorgimento and Aurora Leigh, her nine book epic poem, based on Madame de Sta�l's Corinne ou Italie, with two heroines raising the child of one of them born out of wedlock. But more of Aurora Leigh later. For now we must talk of Margaret Fuller.

III. Margaret Fuller

III. Margaret Fuller

" agnificent, prophetic, this new Corinne. She never confounded relations; but kept a hundred fine threads in her hand, without crossing or entangling any." So wrote Emerson on of New England's Margaret Fuller. Born in 1810, her tragic death by drowning occurred 16 July 1850. At age of six Margaret read Latin as well as English and soon after Greek, at 15 revelling in Madame de Sta�l and Petrarch.

agnificent, prophetic, this new Corinne. She never confounded relations; but kept a hundred fine threads in her hand, without crossing or entangling any." So wrote Emerson on of New England's Margaret Fuller. Born in 1810, her tragic death by drowning occurred 16 July 1850. At age of six Margaret read Latin as well as English and soon after Greek, at 15 revelling in Madame de Sta�l and Petrarch.

She travelled to Italy as a journalist, already deeply committed to women's position.

. . . A woman should love Bologna, for there has the spark of intellect in woman been cherished with reverent care. . . they proudly show the monument to Matilda Tambroni, late Greek Professor there. . . In their anatomical hall is the bust of a woman, Professor of Anatomy. In Art they have had Properzia di Rossi, Elizabetta Sirani, Lavinia Fontana, and delight to give their works a conspicuous place. . . In Milan, also, I see in the Ambrosian Library the bust of a female mathematician. These things make me feel that, if the state of woman in Italy is so depressed, yet a good-will toward a better is not wholly wanting. She mentions Adam Mickiewicz's presence and gives their declaration of faith "Every one of the nations a citizen,-every citizen equal in rights and before authorities. To the Jew, our elder brother, respect, brotherhood, aid on the way to his eternal and terrestrial good, entire equality in political and civil rights. To the companion of life, woman, citizenship, entire equality of rights." In Florence he was addressed as the "Dante of Poland ."

Elizabeth Barrett Browning wrote that

Madame d'Ossoli (calling her by her supposed husband's name) was a most interesting woman to me, though I did not sympathize with a large portion of her opinions. Her written words are just naught. She said herself they were sketches, thrown out in haste and for the means of subsistence, and that the sole production of hers which was likely to represent her at all, would be the history of the Italian Revolution. In fact, her reputation, such as it was in America, seemed to stand mainly on her conversation and oral lectures. If I wished any one to do her justice I should say, as I have indeed said, 'Never read what she has written.' The letters, however, are individual, and full, I should fancy of that magnetic personal influence which was so strong in her. I felt drawn toward her during our intercourse; I loved her, and the circumstances of her death shook me to the very roots of my heart. The comfort is that she lost little in this world; the change could not be loss to her. She had suffered, and was likely to suffer more. The American Consul spoke of her work in the Roman Republic's Hospitals. Miss Fuller took an active part in this noble work, and the greater portion of her time, during the entire siege, was passed in the Hospital of the Trinity of the Pilgrims, which was placed under her direction, in attendance upon its inmates.

The weather was intensely hot; her health was feeble and delicate; the dead and dying were around her in every form of pain and horror; but she never shrank from the duty she had assumed. Her heart and soul were in the cause for which these men had fought, and all was done that a woman could do to comfort them in their sufferings. I have seen the eyes of the dying, as she moved among them, extended upon opposite beds, meet in commendation of her unwearied kindness; and the friends of those who then passed away may derive consolation from the assurance that nothing of tenderness and attention was wanting to soothe their last moments. And I have heard many of those who recovered speak with all the passionate fervor of the Italian nature of her, whose sympathy and compassion throughout their long illness fulfilled all the offices of love and affection. Mazzini, the chief of the Triumvirate, - who, better than any man in Rome, knew her worth, - often expressed to me his admiration of her high character; and the Princess Belgioioso, to whom was assigned the charge of the Papal Palace on the Quirinal, which was converted on this occasion into a hospital, was enthusiastic in her praise. And in a letter which I received not long since from this lady, who is gaining the bread of an exile by teaching languages in Constantinople, she alludes with much feeling to the support afforded by Miss Fuller to the Republican party in Italy. Here, in Rome, she is still spoken of in terms of regard and endearment; and the announcement of her death was received with a degree of sorrow which is not often bestowed upon a foreigner, and especially one of a different faith.

She informed me that she had sent for me to place in my hands a packet of important papers, which she wished me to keep for the present, and, in the event of her death, to transmit it to her friends in the United States. She then stated that she was married to the Marquis Ossoli, who was in command of a battery on the Pincian Hill. . . The packet which she placed in my possession, contained, she said, the certificates of her marriage, and of the birth and baptism of her child. . .

On the same day the French army entered Rome, and, the gates being opened, Madame Ossoli, accompanied by the Marquis, immediately proceeded to Rieti, a village lying at the base of the Abruzzi Mountains, where she had left her child in the charge of a confidential nurse, formerly in the service of the Ossoli family. She remained, as you are no doubt aware, some months at Rieti, whence she removed to Florence, where she resided until her ill-fated departure for the United States. During this period I received several letters from her, all of which, though reluctant to part with them, I inclose to your address, in compliance with your request.

There are two sculptures which particularly inspired women in the nineteenth century.

One is Michelangelo's 'Aurora' from the Medici Tomb in the New Sacristy at San Lorenzo. The Republic of Florence commissioned these sculptures. Later Michelangelo wrote a poem for Dawn to speak in which she desires not to awake while the Medici have robbed Florence of her freedom. Elizabeth Barrett Browning wrote about it at length in Casa Guidi Windows and used it for the title of her epic poem, Aurora Leigh.

The other is Hiram Powers' 'Greek Slave'. It appears to be about the War of Greek Independence, in whose cause Lord Byron fought and died. But it is really about Hiram Powers' own knowledge of himself as both American and Native American, and about Italy, which in this period was ground under by Austria, Spain, France and the Pope, as had Greece been by Turkey. Elizabeth Barrett Browning, who was Hiram Powers' great friend and admirer, spoke of him as part Native American. Another sculpture of his is 'The Last of her Tribe', in which an Indian maiden is fleeing from her persecutors. It is exquisite. Elizabeth wrote a powerful sonnet about the 'Greek Slave', which Queen Victoria read. The Queen also saw the sculpture for it was at the centre of the Great Crystal Palace Exhibition she visited, leaning upon her Prince Consort's arm. Margaret Fuller had written:

You seem as crazy about Powers's Greek Slave as the Florentines were about Cimabue's Madonnas, in which we still see the spark of genius, but not fanned to its full flame. . . I consider the Slave as a form of simple and sweet beauty, but that neither as an ideal expression nor a specimen of plastic power is it transcendent. . . To me, his conception of subject is not striking: I do not consider him rich in artistic thought'. She prefers his busts. But she had also written approvingly: 'As to the Eve and the Greek Slave, I could only join with the rest of the world in admiration of their beauty and the fine feeling of nature which they exhibit. The statue of Calhoun is full of power, simple, and majestic in attitude and expressions.'

Hiram Powers' 'Greek Slave' is life size in its proportions. But Hiram Powers also sculpted colossal statues, as did similarly the tiny Harriet Hosmer. One gigantic statue of Calhoun by Powers was shipwrecked, if indeed it did not cause the wreck of the ship on which the Fuller-Ossoli family perished; one marble effigy of a statesman never reached America, another ended at the bottom of the Bay of Biscay. I show his Calhoun in the surviving plaster cast that remained in his studio in Florence until it was purchased by the Smithsonian Museum in 1963.

Madame Ossoli writes to Marchioness Visconti Arconati

I am absurdly fearful about this voyage. Various little omens have combined to give me a dark feeling. Among others, just now we hear of the wreck of the Westmoreland bearing Power's 'Eve."

Just before Margaret sailed Mrs. Browning wrote of their last evening in Florence: The conversation lapsed into a somewhat gloomy and foreboding tone. The Marchese recalled, half-jestingly, an old prophecy made to him when a boy that the sea was hostile to him and that he had been warned never to embark on a voyage. To Miss Mitford EBB wrote: Such gloom had Madame d'Ossoli in leaving Italy! She was full of sad presentiment. Do you know she had her little son give a small Bible as a parting gift to Penini, writing in it, 'In memory of Angelo d'Ossoli,'- a strange, prophetic expression. Pen showed this Bible to Lillian Whiting:.

Angiolino was nourished by means of a goat on shipboard, there being no refrigeration for the Victorian sea voyage. Small pox broke out, Angiolino miraculously recovering, but the Captain died. The first mate failed in navigating the ship and it wrecked off Fire Island. "Neither Margaret's body, nor that of her husband was ever recovered; that of little Angelo was borne through the breakers by a sailor and laid lifeless on the sands. The manuscript of her "History of Italy" was lost in the wreck." The still warm bodies of steward and child and trunk with letters between her husband and herself were all that survived."

IV. The Sea Change

It was this drowning of her friend, in a ship named the 'Elizabeth', 19 July 1850, that paradoxically released Elizabeth to write Aurora Leigh, the best-selling epic novel poem, published in 1856, whose two heroines she models upon Margaret Fuller and upon herself. Aurora Leigh in the poem is based on the two Victorian professional women prose writers, Harriet Martineau and Margaret Fuller, though added to them are Elizabeth's social status of wealth and breeding and her love of Florence, initially taught her by Madame de Stael, while Marian Erle, as the gypsy who teaches herself to read out of books thrown in the rubbish, who is raped, and who bears a child out of wedlock, an 'Angelo', a pomegranate, represents Elizabeth's own predicament as the racial outsider, vulnerable, powerless and poor. In the poem there are not two babies, only one, the surviving Pen Browning. The drowning of Margaret and her baby in the ship 'Elizabeth' thus became a mirroring surrogate for herself and her child, atoning for the death of her brother, Edward Barrett Moulton Barrett, 'Bro', of the slave estates. She had been blocked from writing this intended magnum opus. Though she had already experimented in Lady Geraldine's Courtship, the poem in which she fictionally proposed marriage to Alfred Tennyson and Robert Browning. Now, day after day, she feverishly wrote_Aurora Leigh_'s nine books, the magnificent epic poem, set in Malvern, London, Paris and Florence, giving back to Margaret her drowned voice, resurrecting her and her child - with a sea change - into its pages. A fine tribute from one woman to another, one friend to another. She stuffed its pages between the cushions of her invalid chair when her child came in to play and visitors, such as the Hawthorne family, friends of Margaret, came to call. We recall Hawthorne also made her his Brook Farm heroine in his 1852 Blithedale Romance, Zenobia, who drowns. Thus in her short-lived forty years she is Margaret, Corinna, Aurora and Zenobia.

Bibliography

Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Aurora Leigh and Other Poems. A cura di John Robert Glorney Bolton e Julia Bolton Holloway. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1995.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Aurora Leigh: Romanzo in versi. Trad. italiano da Bruna Dell'Agnese. Firenze: Le Lettere, 2002.

Bell Gale Chevigny. The Woman and the Myth: Margaret Fuller's Life and Writings. Old Westbury, NY: Feminist Press, 1976.

Joseph Jay Deiss.The Roman Years of Margaret Fuller. New York: Crowell, 1969.

Margaret Fuller Bicentennial Panel - A Woman for the Twenty-First Century. The Journal of Universal Unitarian History 34 (2011), 1-32.

****FLORIN WEBSITE � JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO ASSOCIAZIONE, 1997-2024: MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO LATINO,DANTE ALIGHIERI, SWEET NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, & GEOFFREY CHAUCER || VICTORIAN : WHITE SILENCE: FLORENCE'S 'ENGLISH' CEMETERY || ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING || WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR || FRANCES TROLLOPE || || HIRAM POWERS || ABOLITION OF SLAVERY || FLORENCE IN SEPIA || CITY AND BOOK CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS I, II, III, IV, V,VI,VII ||MEDIATHECA 'FIORETTA MAZZEI' || EDITRICE AUREO ANELLO CATALOGUE || FLORIN WEBSITE || UMILTA WEBSITE ||LINGUE/LANGUAGES: ITALIANO,ENGLISH || VITA** New:Dante vivo || White Silence

To donate to the restoration by Roma of Florence's formerly abandoned English Cemetery and to its Library click on our Aureo Anello Associazione's PayPal button:

THANKYOU!