|

|

| (Information by Peter Kessler and Edward Dawson, with additional information by Trish Wilson, from The La Tene Celtic Belgae Tribes in England: Y-Chromosome Haplogroup R-U152 - Hypothesis C, David K Faux, from Who were the Cimmerians, and where did they come from? Anne Katrine Gade Kristensen (Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters, Hist-fil. Medd 57), from Celts and the Classical World, David Rankin (1996), from The Civilisation of the East, Fritz Hommel (Translated by J H Loewe, Elibron Classic Series, 2005), from Europe Before History, Kristian Kristiansen, from Geography, Ptolemy, from Encyclopaedia of European Peoples, Carl Waldman & Catherine Mason (Facts on File, 2006), from A Genetic Signal of Central European Celtic Ancestry, David K Faux, from Investigating Archaeological Cultures: Material Culture, Variability, and Transmission, Benjamin W Roberts & Marc Vander Linden (Eds), from The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World, David W Anthony, from Atlas of British History, G S P Freeman-Grenville (Rex Collins, London, 1979), from The Barbarians, Tim Newark (Blandford Press, 1985), from The Celts in Macedonia and Thrace, G Kazarov, and from External Links: The Works of Julius Caesar: Gallic Wars, and The Natural History, Pliny the Elder (John Bostock, Ed), and Geography, Strabo (H C Hamilton & W Falconer, London, 1903, Perseus Online Edition), and Celtiberia.net (in Spanish).) |

|

| 5th century BC |

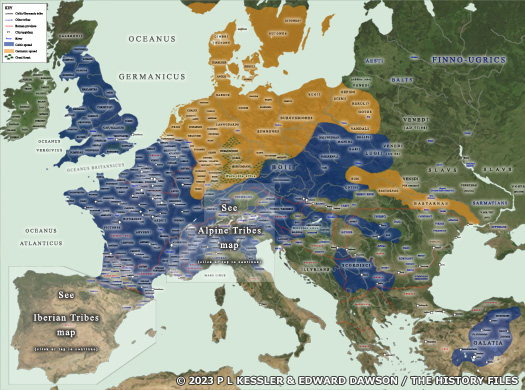

Somewhat complicated to report, the Veneti are a tribe, or confederation, or major grouping, with potential links to the Belgae, who occupy a (semi-theoretical) swathe of territory in Eastern Europe. Similarly, the early Belgae themselves are highly likely to occupy areas of Northern Europe.  Belgic settlement in, or migration across, Northern Europe almost certainly involved some of them entering the Cimbric peninsula where they interacted with early German tribes there, influencing them and being influenced by them Belgic settlement in, or migration across, Northern Europe almost certainly involved some of them entering the Cimbric peninsula where they interacted with early German tribes there, influencing them and being influenced by them |

| Both show differences in their dialect from the La Tène Celts (Gauls) which suggest that they have picked up some influences after settling in their current regions (or, in the Veneti case at least, they have been influenced by Celtic culture from a distance). In the Belgae case, their non-Celtic influence is likely to have come from the proto-Germanic tribes of Scandinavia. Although not universally accepted, generally it is thought that the Belgae begin to migrate around this time, generally heading west towards the Atlantic coast, but possibly also heading east along the Baltic coastline to settle the mouth of the Vistula (if they are not already there) and then to proceed down the river. |

|

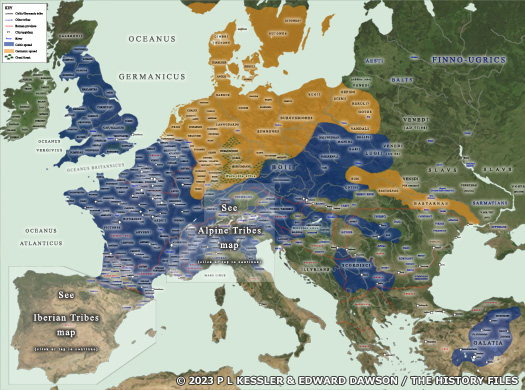

The Atlantic coast division of Belgae settles territory in the modern southern [ Netherlands](FranceHolland.htm#Kingdom of Holland %28Orange%29), Belgium, northern France and Brittany (although even here the later 'western' Veneti are classed as being different both from Belgae and Gauls alike). Along the Vistula, whether created by Eastern Celts or Northern Celts, there are permanent settlements along the river's east bank, in what the Romans later think of as Sarmatia (with Germania to the west). These eastern 'Venedi' may be migrant Belgae, or they may be proto-Italics from the main Yamnaya horizon who have only recently been Celticised by the dominance of that culture.  By around 3000 BC the Indo-Europeans had begun their mass migration away from the Pontic-Caspian steppe, with the bulk of them heading westwards towards the heartland of Europe (click or tap on map to view full sized) By around 3000 BC the Indo-Europeans had begun their mass migration away from the Pontic-Caspian steppe, with the bulk of them heading westwards towards the heartland of Europe (click or tap on map to view full sized) |

|

| 4th century BC |

The Celts (Gauls) of the La Tène culture begin expanding in all directions. The Boii tribe migrates into the region which forms modern Czechia, giving their name to Bohemia (itself only more recently replaced by the Czech name). It may be the Boii or companion tribes which expand La Tène culture into Silesia where it stops the neighbouring Face-Urn culture from expanding. To the west, the Bellovaci cross the Rhine in this century, settling along the rivers Oise and Somme. They establish fresh sacred sites at Saint-Maur and Gournay-sur-Aronde, and later mint their own coins. The Votadini of eastern Britain also quickly exhibit La Tène burial styles, although whether imported or directly imposed is unclear. In his entry for 53 BC, Julius Caesar writes in his Gallic Wars that there had formerly been a time when the Gauls excelled the Germans in prowess, and waged war on them offensively. On account of the great number of their people and the insufficiency of their land, the Gauls had sent colonies over the Rhine. One of these, a division of the powerful Volcae Tectosages, had seized fertile areas of what is now Germany, close to the Hercynian Forest (known to the Greeks as Orcynia), and had settled there. Additionally, according to Julius Caesar, the Belgic tribe of the Atrebates had invaded northern Gaul from previous territory in Germany. They repeat the invasion in the second century BC, probably to settle there permanently (it is unlikely to be coincidental that Belgic tribes begin to leave Germany just as Gauls are greatly expanding into it).  The Riesengebirge was part of the once-vast Hercynian Forest which spread eastwards from southern Germany and which proved a serious impediment to Roman expansion The Riesengebirge was part of the once-vast Hercynian Forest which spread eastwards from southern Germany and which proved a serious impediment to Roman expansion |

| 389 BC |

Brunnus and his Senones Celts sack Rome, with only the Capitoline Hill standing out against them. The citizens of Rome are forced to pay a thousand pounds in gold to buy off the Celts (a pretty low sum by Roman standards, which perhaps outrages them more than the city being sacked in the first place). This perhaps allows the Etruscans themselves a respite from the incessant pressure from the Latins, although the city of Clevsin is allied to Rome for the duration of the Celtic incursion. |

| c.325 BC |

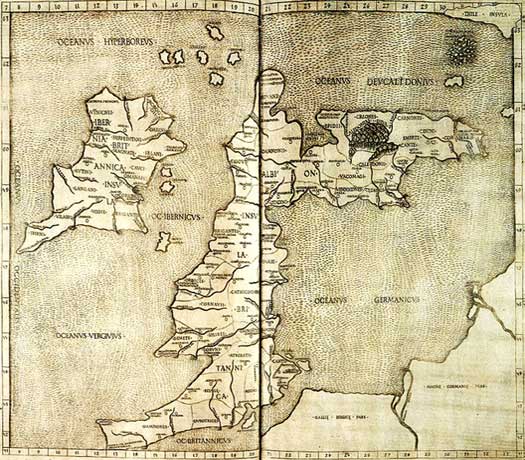

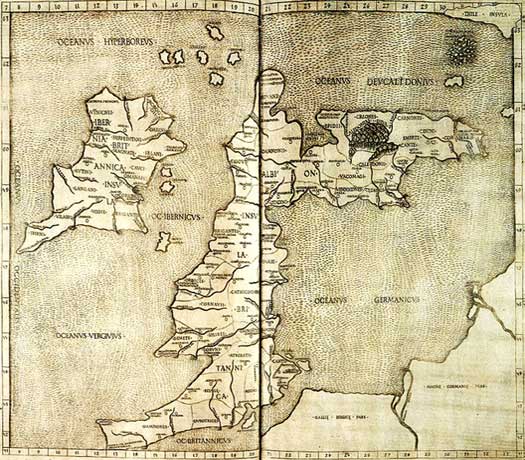

Pytheas of Massalia undertakes a voyage of exploration to north-western Europe, becoming the first scholar to note details about the Celtic and Germanic tribes there (see feature link). One of the tribes he records is the Ostinioi - almost certainly the Osismii - who occupy Cape Kabaïon, which is probably pointe de Penmarc'h or pointe du Raz in western Armorica. This means that the tribe has already settled the region by the mid-fourth century, probably alongside their neighbours of later years, the Veneti, Cariosvelites, and Redones. Pytheas of Massalia undertakes a voyage of exploration to north-western Europe, becoming the first scholar to note details about the Celtic and Germanic tribes there (see feature link). One of the tribes he records is the Ostinioi - almost certainly the Osismii - who occupy Cape Kabaïon, which is probably pointe de Penmarc'h or pointe du Raz in western Armorica. This means that the tribe has already settled the region by the mid-fourth century, probably alongside their neighbours of later years, the Veneti, Cariosvelites, and Redones.  The details recorded by Pytheas were interpreted by Ptolemy in the second century AD, and this 1490 Italian reconstruction of the section covering the British Isles and northern Gaul shows Ptolemy's characteristically lopsided Scotland at the top The details recorded by Pytheas were interpreted by Ptolemy in the second century AD, and this 1490 Italian reconstruction of the section covering the British Isles and northern Gaul shows Ptolemy's characteristically lopsided Scotland at the top |

| c.300 BC |

By this time, a little-known Etruscan city near the modern town of Marzabotto, close to Bologna, has greatly declined since its sixth century BC founding. Its role suddenly nosedives to the status of a military outpost following massive Celtic incursions into the Po Valley. Farther away from the Central European heartland of Celtic territory, the last stages of Hallstatt culture sees Celts involved in a great expansion into southern and Eastern Europe. Tribes infiltrate across the Danube to enter the land on the southern edge of the Eastern Alps, in the form of the Latovici, Serapili, Sereti, and Taurisci. The native communities in the hinterland of the Adriatic between Carinthia and Carniola are relatively rapidly assimilated by the Celtic newcomers, soon losing their identity completely. The migration turns into a powerful juggernaut as it enters the Balkans to come up against the [Thracian](GreeceThrace.htm#Odrysian Restored) and Greek kingdoms (especially a weakened Macedonia) in 279-277 BC. |

| 282 - 281 BC |

The Etruscan city of Pupluna suffers badly during Rome's wars against the Boii, this being the group which had sent a migratory splinter group into Italy in the fourth century BC. Having seen the expulsion by Rome of the Senones in the previous year, the Boii raise a general levy which includes Etruscans before setting out to meet the Romans on the battlefield. Near Lake Vadimonis the battle sees the Etruscans suffer the loss of more than half their men, while hardly any of the Boii escape alive.  Dictator Marcus Furius Camillus may have been instrumental in persuading Brennus and his Gauls to leave Rome following its sacking in 389 BC, as painted around 1716-1720 Dictator Marcus Furius Camillus may have been instrumental in persuading Brennus and his Gauls to leave Rome following its sacking in 389 BC, as painted around 1716-1720 |

| The following year the Boii and Etruscans try again. This time everyone is armed, including youths who have only just reached manhood. Again they are decimated and completely defeated, and this time they surrender, sending ambassadors to Rome to conclude a treaty. Polybius writes that constant defeats at the hands of the Gauls had inured the Romans to the worst which could befall them, so that they are able to fight the Boii on this occasion like trained and experienced gladiators. The Gauls maintain peace with Rome for forty-five years following this event. |

|

| 279 - 277 BC |

Celtic tribes are arriving in the Balkans and Anatolia by this time. In one encounter with the peoples already there, the Antigonid empire successfully smashes an invasion of Celts into Greece. Caesar later notes in his journals that 'sometime' before the first century BC the Belgic tribes had emigrated from somewhere to the east of the Rhine. In fact, according to many authors, the archaeological record argues for an earlier date for the first Belgic settlers to the north of Gaul. Artefacts of European origin which date from the third century BC strongly suggest that the Belgae cross into Britain at about the same time as they settle the northern edge of Gaul. They appear to arrive as fairly small warrior groups which quickly integrate into the elite of the local communities. Other groups seem to remain behind, in northern Germany, to be assimilated by Germanics such as the Marsigni.  Climate-induced drought in the thirteenth century BC created great instability in the entire eastern Mediterranean region, resulting in mass migration in the Balkans, as well as the fall of city states and kingdoms further east (click or tap on map to view full sized) Climate-induced drought in the thirteenth century BC created great instability in the entire eastern Mediterranean region, resulting in mass migration in the Balkans, as well as the fall of city states and kingdoms further east (click or tap on map to view full sized) |

| Tribes which belong to the Belgae included the Ambiani, Atrebates, Bellovaci, Caleti, Menapii, Morini, Nervii, Remi, Suessiones, Veliocasses, and Viromandui. Caesar states that one tribe, the Atuatuci, are descended from the semi-Germanic Cimbri and Teutones, and describes four others, the Caerosi, Condrusi, Eburones, and Paemani, as Germanic tribes (although Ambiorix, a later leader of the Eburones, has a Celtic name). Other tribes which may be included amongst the Belgae are the Leuci, Mediomatrici, Treveri, and Tungri. The Remi are the most prominent tribe. Their capital, Durocortum (modern Reims in France), becomes the capital of the Roman province of Gallia Belgica. |

|

| 273 - 214 BC |

Celts invade [Thrace](GreeceThrace.htm#Odrysian Restored) again, destroying the Thracian kingdom and forcing the Greek aristocracy to escape to the colonies bordering the Black Sea. The kingdom of Galatia is created in Thrace by the victorious Celts, only to be destroyed by the Thracians in 214 BC and forced to concentrate itself entirely in Anatolia. The remaining bulk of Celts in the Balkans settles into the powerful Scordisci confederation. |

| c.250 BC |

Germanic settlements have spread only a little farther south-westwards along the North Sea coastline, and eastwards into the heart of modern Poland and northern Germany. One exception to this is the tribe of the Bastarnae (whose ethnic background is highly uncertain, but evidence tends to support the idea that they are originally Celtic). They have already reached the Balkans by this time.  Many Belgic groups showed marked Germanic influences, so were they Celts with German words and warriors, or Germans with Celtic words and warriors? The truth probably lies somewhere in between Many Belgic groups showed marked Germanic influences, so were they Celts with German words and warriors, or Germans with Celtic words and warriors? The truth probably lies somewhere in between |

| Between this point and the beginning of the first century AD, Germanic expansion and migration continue this slow progression, extending into modern Belarus, Russia and Ukraine, and southwards towards modern Switzerland, central Germany, and Czechia, Slovakia, and Hungary. All the while, Celtic tribes are being edged out or absorbed. |

|

| 236 BC |

Celtic (Gaulish) tribes in northern Italy have maintained an unbroken peace with Rome for forty-five years, the last battles having been fought against the Boii. A new generation is now in command of the tribes and is eager to test itself against the common enemy. These tribal chiefs inflate trivial excuses in their cause, and invite the Alpine Gauls to join the impending fray. This is the first that the majority of the tribesmen know of the intended renewal of hostilities, and the Boii immediately form a conspiracy against their own leaders, as well as against the newcomers. A Gaulish king who acts without the support and consent of his own people places considerable risk on his own safety. Atis and Galatus of the Boii are put to death, and the tribe cuts itself to pieces in a pitched battle. Rome, alarmed at the threatened invasion, is able to recall its dispatched army.  This map shows not only the greatest extent of Etruscan influence in Italy, during the seventh to fifth centuries BC, but also Gaulish intrusion to the north, which compressed Etruscan borders there (click or tap on map to view on a separate page) This map shows not only the greatest extent of Etruscan influence in Italy, during the seventh to fifth centuries BC, but also Gaulish intrusion to the north, which compressed Etruscan borders there (click or tap on map to view on a separate page) |

| 232 BC |

Five years after the threat of war between Gauls and Rome had ended in Gaulish internecine battle, during the consulship of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, Rome divides the territory of Picenum, from which the Senones had been ejected in 283 BC. For many of the Gauls, and especially the Boii whose lands border this territory, this is an act of war. The tribes are now convinced that Rome wants to destroy and expel them completely. |

| 231 - 225 BC |

Over the next six years or so, the two most extensive tribes, the Boii and Insubres, send out the call for assistance to the tribes living around the Alps and on the Rhône. Rather than each of the tribes sending their own warriors, it appears that individual warriors are hired from the entire Alpine region as mercenaries. Polybius calls them Gaesatae, describing it as a word which means 'serving for hire'. They come with their own kings, Concolitanus and Aneroetes, who have probably been elected from their number in the Celtic fashion. |

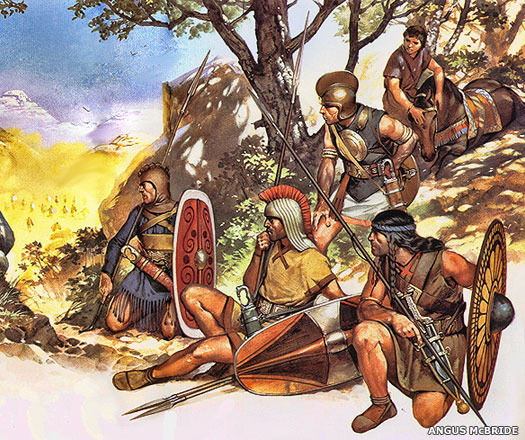

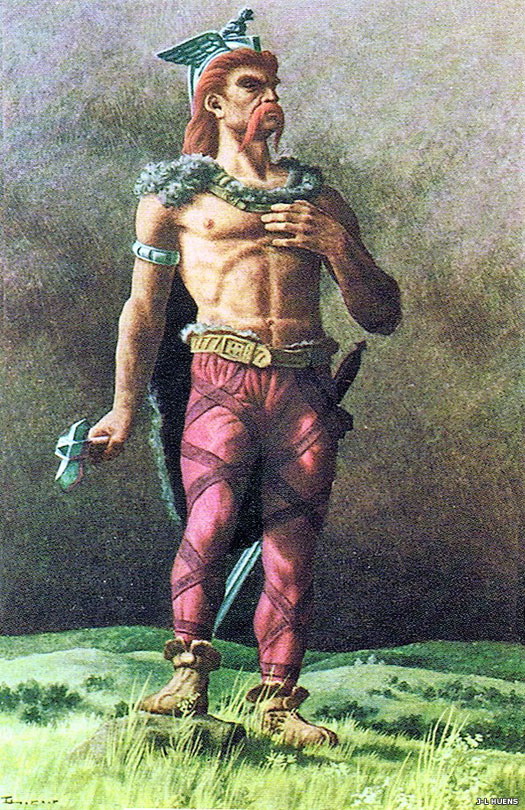

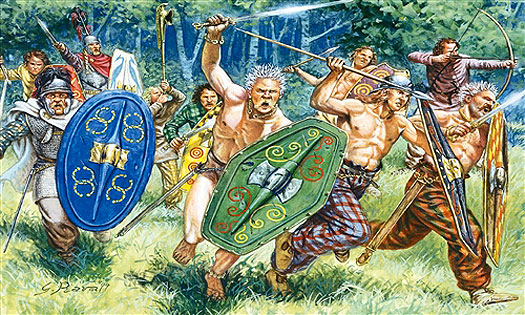

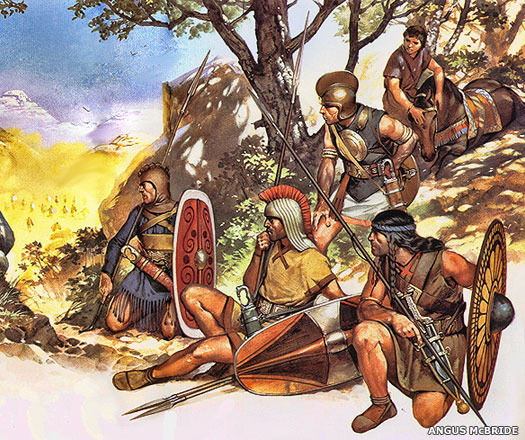

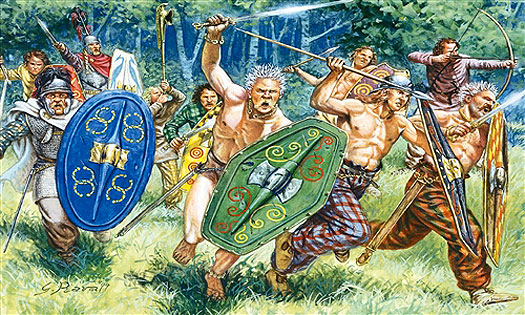

The Gaesatae are offered a large sum of gold on the spot and the wealth of Rome is also pointed out - wealth which can be theirs if they stick to their task. The mercenaries are easily persuaded, and they are proud to remind other Gauls of the old campaign which had been undertaken by their own ancestors in which they had seized Rome. This strongly suggests that a proportion of the Gaesatae (probably including their kings) are descended from members of the Senones tribe, as it had been this tribe which had led the occupation of Rome in 389 BC.  While most of the Gauls of the third century BC fought fully clothed, their Gaesatae mercenaries tended to fight with nothing more than their weapons, and not even the trousers shown here While most of the Gauls of the third century BC fought fully clothed, their Gaesatae mercenaries tended to fight with nothing more than their weapons, and not even the trousers shown here |

|

Rome has been informed of what is coming, and hurries to assemble the legions. Even its ongoing conflict with the Carthaginians takes second place, and a treaty is hurriedly agreed with Hasdrubaal, commander in Iberia, which virtually confirms Carthaginian dominance there. Such is Rome's haste that they approach the Gaulish frontier before the Gauls have even stirred. It is 225 BC when the Gaesatae forces cross the Alps and enter the valley of the Padus with a formidable army, furnished with a variety of armour. The Boii, Insubres, and Taurini accompany them but the Cenomani and Adriatic Veneti are persuaded to side with Rome, forcing the Gauls to detach a force to guard their flank. Despite this, their main army consists of about a hundred and seventy thousand foot and horse, which petrifies the Romans and reminds them of 389 BC. As well as the four new legions, The Romans are accompanied by Etruscans, Sabines, Sarsinates, and Umbri, and more Cenomani and Veneti. Defending Rome and its territories are Ferrentani, Iapygians, Latins, Lucanians, Marrucini, Marsi, Messapians, Samnites, and Vestini, plus two more legions on Sicily and in Tarentum. The first battle, when it comes, is near Faesulae, outside the subjugated Etruscan city of Clevsin. The Romans are decimated and routed by superior Gaulish tactics. A fresh army under Lucius Aemilius arrives, and Aneroetes counsels retreat with their booty and army intact, ready to launch a fresh attack when ready.  The Sabini settlement of Reate (modern Rieti) was founded by the Sabini and prospered under Roman control to survive into the modern age The Sabini settlement of Reate (modern Rieti) was founded by the Sabini and prospered under Roman control to survive into the modern age |

|

| Consul Gaius Atilius lands at Pisae with the Sardinian legion and the Gauls find themselves caught between two Roman armies. The battle is fierce, and the Gauls gain the head of Gaius Atilius. However, the battle turns against them and large numbers of Gauls are cut down or taken prisoner, including Concolitanus. Aneroetes is able to flee with his band of followers, and they commit suicide together. |

|

| 224 BC |

Buoyed by its victory, Rome attempts to clear the entire valley of the Padus. Two legions are sent under the command of the consuls of that year, and the Boii are terrified into submission. However, incessant rain and an outbreak of disease prevents the legions from achieving anything greater. |

| 223 BC |

Two fresh consuls lead two more legions into the Padus, marching through the territory of the Anamares, who live not far from Placentia (some readings of the original text translate this as the Ananes and their home in the Marseilles region, which would be impossible given the nature of this campaign). They secure the friendship of this tribe and cross into the country of the Insubres, near the confluence of the Adua and Padus. Some skirmishing aside, peace is agreed with this tribe, and the Romans head for the River Clusius. There they enter Cenomani lands, with these allies providing some reinforcements. Then the Romans return to the Insubres and begin laying waste to their land. The tribe is faced with no choice but to fight, and their defeat is all but inevitable.  The Celtic tribes of northern Italy were large and dangerous to the Romans, unlike their fellow Celts in the Western Alps, who were relatively small in number and fairly fragmented, although they made up for that by being even more belligerent than their easterly cousins The Celtic tribes of northern Italy were large and dangerous to the Romans, unlike their fellow Celts in the Western Alps, who were relatively small in number and fairly fragmented, although they made up for that by being even more belligerent than their easterly cousins |

| 222 BC |

With peaceful overtures by the Insubres being firmly rejected by Rome, the tribe calls on the Gaesatae once more. Together they fight the Romans and withdraw intact to Mediolanum. The stronghold is stormed by the Romans and, following some hard fighting, the Insubres are left with no option but to surrender, their unnamed chief making a complete submission to Rome. This act effectively ends the Gallic War in northern Italy, as Rome now dominates all of the tribes there. |

| 156 BC |

Having recently defeated the Macedonian kingdom in the Third Macedonian War, Rome appears to be dominant in south-eastern Europe. Little resistance is expected from the various tribes of Greece, [Thrace](GreeceThrace.htm#Odrysian Restored), and the Balkans. And yet it takes a century and-a-half to fully subdue both the hard-fighting Thracian tribes and the Dacians and Celts of the Balkans - especially the Celts of the Scordisci confederation. In this year a minor clash takes place between Rome and the Scordisci, although the details and location are unknown. |

| c.150 BC |

Metal coinage comes into use in Britain. There is now widespread contact with continental Europe through the island's southern and eastern Celtic tribes, establishing links which will survive until the Roman invasion.  The Kirkburn sword was one of the greatest treasures to be unearthed from the East Yorkshire region. Dated to 300-200 BC, it comes from the grave of a Celtic man The Kirkburn sword was one of the greatest treasures to be unearthed from the East Yorkshire region. Dated to 300-200 BC, it comes from the grave of a Celtic man |

| 133 BC |

With the fall of the city of Numantia in Iberia, the Celtiberians are conquered by Rome. To achieve this, it has taken sixty-two years of Roman fighting since the first Celtic submission to them in the Iberian peninsula. |

| 119/117 BC |

Although generally ascribed to 119 BC, Kazarov places this event in 117 BC. After a general period of peace which has lasted for more than fifteen years, the Scordisci manage to push all the way through the Roman defences in the southern Balkans, reaching the Aegean coast. The Roman governor of Macedonia, Pompeius, is killed during an attack on Argos. A force led by Quaestor Marcus Annius finally ends their adventure, pushing them back. A subsequent attack by the Scordisci together with the Thracian Maedi tribe is also repulsed. The involvement of the Maedi tribe in the second attack marks the beginning of a new, more widespread involvement in the frequent campaigns between Romans and barbarians. While the Celts in Thrace and the lower Balkans continue to offer the biggest threat to Roman expansion, the native Balkan tribes frequently support them, especially the Bastarnae, Dardani, and the free Thracian tribes (the Bessoi, Denteletes, Maedi, and Triballi).  If the Bastarnae were ever paid in coin for their efforts in Macedonia then they would have received coins like this, bearing the head of Philip V of Macedonia If the Bastarnae were ever paid in coin for their efforts in Macedonia then they would have received coins like this, bearing the head of Philip V of Macedonia |

| It takes this Macedonian raid to make Rome fully aware of the severity of the threat to its security in the region. The war between Rome and the tribes in the Balkans rumbles on for decades, becoming increasingly bloody and vicious. |

|

| 113 - 102 BC |

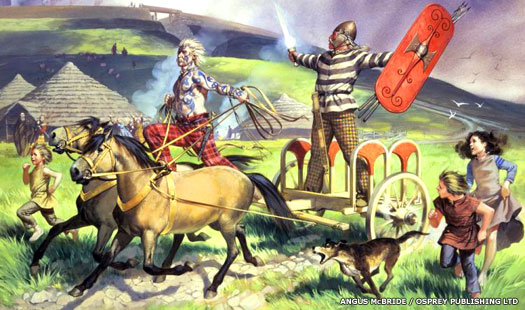

In central Germany, members of the Helvetii peoples join a large-scale migration of semi-Germanic Cimbri and Teutones from their homeland in what later becomes central and northern Denmark. The wandering tribes enter Gaul from Germany in 109 BC, causing chaos amongst the Celtic tribes there and rendering critical the situation in the region. It is almost certainly this invasion which sparks a migration of Belgic peoples from the [ Netherlands](FranceHolland.htm#Kingdom of Holland %28Orange%29) and northern Gaul into south-eastern Britain, although such a migration may already have started on a smaller scale. |

| 1st century BC |

By the first century BC the Venedi are known to occupy a great swathe of territory which stretches from the mouth of the Vistula to what is now western Belarus and western Ukraine. They may even have absorbed Belgic groups which could potentially have migrated there from northern Germany, although the lack of any written evidence makes their history extremely uncertain and open to interpretation.  For a seagoing people like the Belgae, it would have been a fairly simple process to sail along the southern waters of the Baltic and enter a wide river mouth such as the Vistula - settlement quickly followed, spreading south along the river's east bank between the fifth or fourth centuries BC and the first and second AD For a seagoing people like the Belgae, it would have been a fairly simple process to sail along the southern waters of the Baltic and enter a wide river mouth such as the Vistula - settlement quickly followed, spreading south along the river's east bank between the fifth or fourth centuries BC and the first and second AD |

| c.60 BC |

Diviciacus of the Suessiones (not to be confused with Diviciacus of the Aeduii) holds sway not only amongst a large proportion of the continental Belgic tribes but also over parts of south-eastern Britain, according to Julius Caesar. This would suggest a form of high kingship over Belgic tribes which had recently migrated there, such as the British Belgae, the Cantii, and perhaps the Catuvellauni and Trinovantes. This unity of tribes is reflected in their characteristic triple-tailed horse coins from about 60 BC. |

| c.60 - 40 BC |

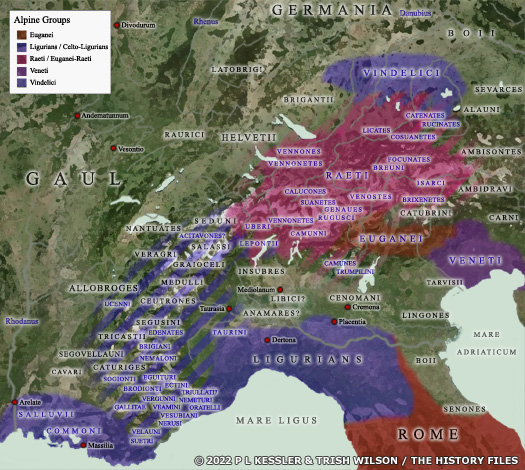

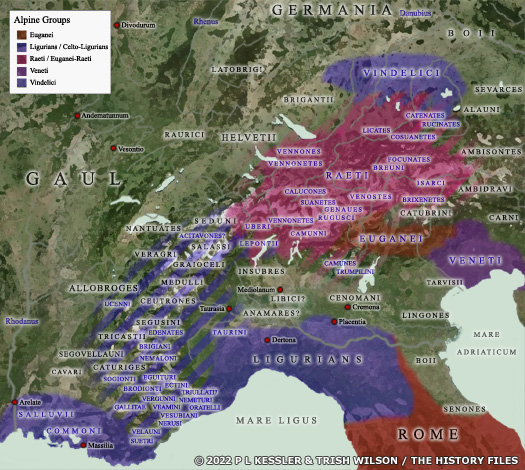

From the latter part of the first century BC and into the next century, various historians mention a variety of tribes and their affiliates which are uniformly identified as being Taurisci, together with a variety of other Cisalpine tribes which include the Norici and Iapydes (not all of which are Celtic in origin, despite some claims). Strabo mentions the Taurisci in his Natural History as being strictly Celtic, as does Livy writing the History of Rome around 10 BC. Pliny the Elder, writing his own Natural History in the mid-first century AD, does the same, along with Apian and Cassius Dio in the second and third centuries AD, saying that the Taurisci are a warrior-like tribe which often plunders Roman territory in the hinterlands of Tergestica (modern Trieste) - this at a time in which various Celtic peoples are largely being Romanised or Germanised. The other tribes which are mentioned as individual groups of the Taurisci confederation include: the Carni, who occupy the Carnian Alps, on the edge of the south-eastern Alps; the Latovici between Krka and Sava; the Varciani along the Sava towards Sisak; the Serapili and Sereti along the River Drava on the edge of Pannonia; and the Iasi towards Varaždin.  The origins of the Euganei, Ligurians, Raeti, Veneti, and Vindelici are confused and unclear, but in the last half of the first millennium BC they were gradually being Celticised or were combining multiple influences to create hybrid tribes (click or tap on map to view full sized) The origins of the Euganei, Ligurians, Raeti, Veneti, and Vindelici are confused and unclear, but in the last half of the first millennium BC they were gradually being Celticised or were combining multiple influences to create hybrid tribes (click or tap on map to view full sized) |

| Ancient authors also list several smaller indigenous communities, such as the Illyrian Colapiani along the River Kolpa, the Celtic Ambisontes in the Soča Valley, the Subocrini around Razdrto, and the Rundicti in the Kras and Notranjska regions. The great Tauriscan tribal community with its many smaller tribes (only some of which can be identified as above) has never developed into a state formation. |

|

| 60 - 58 BC |

The Helvetii begin an invasion of the lowlands of western Gaul, and Julius Caesar recruits two new legions to face the threat. After some skirmishing, the two sides face each other at the Battle of Bibracte in 58 BC, and the Helvetii are mercilessly crushed by six Roman legions. Their shattered remnants are forced back to their homeland, but are now unable to fight off Germanic incursions which could also threaten Gaul. Julius Caesar allows the relatively hospitable Boii to settle a buffer zone to the north of the Helvetii and east of the Aeduii, but even this shift leaves gaps for Germanic incursions, and one is already underway to the north. Caesar receives a federation of chiefs from tribes which include the Sequani, all of whom are suffering thanks to the Suebic invasion under Ariovistus.  The Harz is now a national park in Germany to ensure that this primeval forest survives, but in the first century BC it was probably home to the Suevi The Harz is now a national park in Germany to ensure that this primeval forest survives, but in the first century BC it was probably home to the Suevi |

It is this campaign and its mixed outcome, despite victory in battle, which triggers Julius Caesar's campaigns in western Gaulish lands from this point onwards, which result in the eventual annexation of a vast swathe of territory into the Roman state as the province of Gaul. In the Balkans, and following a recent success in battle at Histria, relations between the Getae and their neighbours undergoes a notable deterioration. Suddenly, under the leadership of Burebista, who is apparently guided by a wizard called Deceneus, the Getae launch a succession of brutal attacks on their former allies. The Celts seem to be first on the list, although the Eravisci escape unscathed. The territory of the Boii and Taurisci are laid waste, with the Boii especially being almost genocidally exterminated by Burebista's brutal onslaught. Their territory is subsequently known as the deserta Boiorum (effectively meaning the Boii wastelands, with 'deserta' meaning 'empty lands', or at least land which is sparsely populated). The Scordisci follow, their previously unassailable heartland laid open. Next to face Burebista's onslaught are the Bastarnae in Dobruja, who are apparently 'conquered', and then the largely defenceless western Greek Pontic cities. This period coincides with the end of local coin production by the Celts and Bastarnae, showing that the cultural and economic status quo has been fatally disrupted.  The Roman troops of Julius Caesar prepare to face the Helvetii and their allies (which probably include some Boii elements) at the Battle of Bibracte in 58 BC, outside the oppidum of the Aeduii tribe The Roman troops of Julius Caesar prepare to face the Helvetii and their allies (which probably include some Boii elements) at the Battle of Bibracte in 58 BC, outside the oppidum of the Aeduii tribe |

|

| 58 BC |

The Gallic Wars of Julius Caesar begin when he becomes governor of Gaul. Over the course of the next decade or so, he conquers all of the Gaulish tribes in the region. His efforts begin with a showdown against Ariovistus of the Suevi at the Battle of Vosges. The Suevi host lines up in units of tribal groups starting with the Harudes, Marcomanni, Triboci, Vangiones, Nemetes, Sedusii and the core of the Suebi themselves. Superior Roman tactics breaks that line and the Suevi host makes a run for the Rhine. Ariovistus makes it across, but many of his allies now turn on him and the Suebi. It is Caesar who records the existence of the Suebi, differentiating them from the tribe of the Cherusci, but now they avoid the Rhine for generations, concentrating on building a fresh confederation in central Germania. |

| 57 BC |

The Belgae enter into a confederacy against the Romans in fear of Rome's eventual domination over them. They are also spurred on by Gauls who are unwilling to see Germanic tribes remaining on Gaulish territory and are unhappy about Roman troops wintering in there. The Senones are asked by Julius Caesar to gain intelligence on the intentions of the Belgae, and they report that an army is being collected. Caesar marches ahead of expectations and the Remi, on the Belgic border, instantly surrender, although their brethren, the Suessiones remain enthusiastic about the venture. The Bellovaci are the most powerful among the Belgae, but the confederation also includes the Ambiani, Atrebates, Atuatuci, Caerosi, Caleti, Condrusi, Eburones, Menapii, Morini, Nervii, Paemani, Veliocasses, and Viromandui, along with some unnamed Germanics on the western side of the Rhine.  The gentle rolling landscape of the Limberg region would have made idea pasture and farming land for the Belgic tribes, but its proximity to the Maas would have provided the woods and swamps which served as a refuge in times of need The gentle rolling landscape of the Limberg region would have made idea pasture and farming land for the Belgic tribes, but its proximity to the Maas would have provided the woods and swamps which served as a refuge in times of need |

Caesar encourages his ally, Diviciacus of the Aeduii, to attack the Bellovaci and divert part of the Belgic forces. The remaining Belgae march against the Romans en masse, attacking the Remi town of Bibrax along the way. Rather than face such a large force with a reputation for uncommon bravery, Caesar elects to isolate them in groups using his cavalry. He confronts the Bellovaci in battle, during which they learn that Diviciacus and the Aeduii are approaching their territories. They leave the battlefield in some disorder to attempt to head off the Aeduii, but Roman troops are able to follow them and cut down large numbers of men before breaking off. The next day, Caesar leads his army into the territories of the Suessiones, to capture the town of Noviodunum. With this victory, the Suessiones surrender and Caesar marches on the surviving Bellovaci, who take refuge in their town of Galled Bratuspantium. Diviciacus of the Aeduii pleads for the former allies of his people, whose leaders in the confederacy against Rome had already fled to Britain. With the Bellovaci subdued, Caesar receives the surrender of the Ambiani, while the Nervii, refusing any surrender, assemble with the Atrebates and Viromandui to offer battle.  The Aeduii confederation is shown here, around 100 BC, with borders approximate and fairly conjectural, based on the locations of the tribes half a century later - it can be seen that the Aulerci at least migrate farther north-west during that time, although the remainder largely stay put (click or tap on map to view full sized) The Aeduii confederation is shown here, around 100 BC, with borders approximate and fairly conjectural, based on the locations of the tribes half a century later - it can be seen that the Aulerci at least migrate farther north-west during that time, although the remainder largely stay put (click or tap on map to view full sized) |

|

The Atuatuci are expected to join them, but the Nervii launch an early surprise attack at the Battle of the Sabis (probably the River Selle). The Romans are supported by auxiliaries sent by the Treveri, while the Nervii are backed up by the Atrebates. The attack surprises the Romans, but they rally and turn potential defeat into a near-massacre of the Nervii. The Atuatuci, who had been marching to the assistance of the Nervii, return home once they hear that they have missed the battle. They are attacked there by the Romans and are completely defeated. The region which had been inhabited by the Atuatuci on the western side of the Rhine is now left entirely depopulated when Caesar sells all surviving tribal members into slavery, which amounts to something like fifty-three thousand individuals. According to Caesar, the Aulerci, Cariosvelites, Osismii, Redones, Sesuvii, Venelli, and Veneti, all of whom are located along the Atlantic coast, are subdued by the legion of Publius Licinius Crassus. With this action, northern Gaul has been brought under Roman domination, while the victorious legions winter amongst the Andes, Carnutes, and Turones.  The thick forest of the Ardennes formed part of the Treveri homeland when they arrived there in the early or mid-second century BC The thick forest of the Ardennes formed part of the Treveri homeland when they arrived there in the early or mid-second century BC |

|

| 56 BC |

Following his successful campaign against the Belgae in the previous year, Caesar heads for Italy. He sends Servius Galba ahead with the Twelfth Legion and part of the cavalry to secure the way. The pass through the Alps has been dominated by the Nantuates, Seduni, and Veragri tribes, making the route a dangerous one for Roman merchants, and now is the time to end that danger. Galba conducts a few successful battles and storms several of their forts, until the tribes send embassies and hostages, and peace is concluded. Galba stations two cohorts amongst the Nantuates, and sets up camp with the legion's remaining cohorts in the village of Octodurus, which belongs to the Veragri. The village is situated in a valley with a small plain, and is bounded on all sides by very high mountains. Galba takes the unoccupied half of the village as winter quarters for his troops, and fortifies it with a rampart and ditch. Several days later, the tribe has vanished from the village and has assembled in the mountains overlooking the valley with a very large force of Nantuates and Seduni. The legion, which is reduced in size after detachments have been made, appears vulnerable to the Celts, who are convinced that the Romans want to conquer all of Gaul. The Romans decide to defend their position, and are hard-pressed by the superior numbers attacking them, perhaps thirty thousand in all. The six hour battle ends when the exhausted Romans make a last-ditch sally which takes the Celts by surprise and inflicts heavy casualties on them, forcing them to withdraw. Having survived the onslaught the Romans withdraw in good order, heading westwards into the territory of the Allobroges where they settle into safer winter quarters.  The region around the Great St Bernard's Pass was a perfect mix of fertile plains and protective high mountains for small but aggressive Celtic tribes in the four centuries or so between their settlement of the area and domination by Rome The region around the Great St Bernard's Pass was a perfect mix of fertile plains and protective high mountains for small but aggressive Celtic tribes in the four centuries or so between their settlement of the area and domination by Rome |

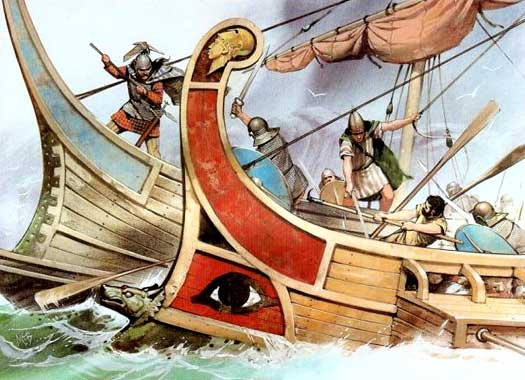

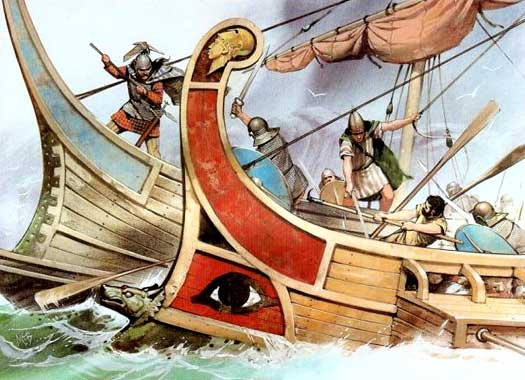

With Gaul now apparently at peace, Caesar sets out for Illyricum. Once he has left, war flares up again, triggered by Publius Licinius Crassus and the Seventh Legion in the territory of the Andes. With supplies of corn running low, he sends scavenging parties into the territories of the Cariosvelites, Esubii, and the highly influential Veneti. The latter revolt against this infringement of their lands and possessions, and the neighbouring tribes rapidly follow their lead, including the Ambiliati, Diablintes, Lexovii, Menapii, Morini, Namniti, Nannetes, and Osismii. The Veneti also send for auxiliaries from their cousins in Britain. Julius Caesar rushes back to northern Gaul, to a fleet which is being prepared for him by the (Roman-led) Pictones and Santones on the River Loire. The Veneti and their allies fortify their towns, stock them with corn harvests from the surrounding countryside, and gather together as many ships as possible. Knowing that the overland passes are cut off by estuaries and that a seaward approach is highly difficult for their opponents, they plan to fight the Romans using their powerful navy in the shallows of the Loire. Before engaging the Veneti, Caesar sends troops to the Remi, Treveri, and other Belgae to encourage them to keep to their allegiance with Rome and to hold the Rhine against possible incursions by Germanics who may be planning to join the Veneti. This works, with even the previously militantBellovaci remaining subdued during this revolt.  Roman auxiliaries in the form of the Aeduii attack a Veneti vessel in Morbihan Bay on the French Atlantic coast during the campaign of 56 BC Roman auxiliaries in the form of the Aeduii attack a Veneti vessel in Morbihan Bay on the French Atlantic coast during the campaign of 56 BC |

|

Crassus is sent to Aquitania and Quintus Titurius Sabinus to the Cariosvelites, Lexovii and Venelli, to prevent them sending reinforcements to the Veneti. Sabinus finds that Viridovix of the Venelli has joined the revolt, along with the Aulerci and Sexovii, who have killed their magistrates for wanting to remain neutral. Sabinus remains in his well-fortified camp, resisting the taunts of the Venelli and their allies until they venture too far forwards, allowing a Roman sally across the defensive ditch and into the fleeing Celtic ranks. This area of the revolt is instantly extinguished. The campaign by Caesar against the Veneti is protracted and takes place both on land and sea. Veneti strongholds, when threatened, are evacuated by sea and the Romans have to begin again. Eventually the Veneti fleet is cornered and defeated in Quiberon Bay by Legate Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus. The Veneti strongholds are stormed and much of the Veneti population is either captured and enslaved or butchered. The confederation is destroyed and Roman rule is firmly stamped upon the region. Entering Aquitania, Crassus recruits auxiliaries from the Gaulish regions of Tolosa, Carcaso, and Narbo (which includes the tribes of the Bebryces, Sordones, and Volcae) before entering the territory of the Sotiates. That tribe has gathered together a large force which attacks the Romans in a drawn-out and vigorously-contested engagement. The Romans are only just victorious, having outlasted their hot-headed Celtic opponents in terms of stamina. The tribe's oppidum is besieged and they eventually surrender, despite an attempt by Adcantuannus to lead his personal retinue into a death or glory attack and other Celts undermining the siege towers (thanks to the presence of copper in the region these Celts are expert miners).  The Garonne in south-western France provided a defining line between the lands of the Gauls to the north and those of the Aquitani to the south, although by the first century BC this definition had blurred somewhat The Garonne in south-western France provided a defining line between the lands of the Gauls to the north and those of the Aquitani to the south, although by the first century BC this definition had blurred somewhat |

|

Crassus marches into the territories of the Vocates and Tarusates. They prove to be a rather more difficult opponent. The campaign against the Sotiates has given them time to raise troops from northern Iberia, many of which had fought with Quintus Sertorius, a rebellious governor of Iberia who had defied Rome for a decade, and they have learnt a great deal from that experience. They outnumber Crassus perhaps by ten-to-one and hold a very strong position which prevents him from gathering supplies for his men. The only option (aside from an unthinkable retreat) is to engage them in battle, despite the odds. Pinning them down at the front, he sends cavalry around to their rear to scout out any weakness. Their entirely unguarded rear is attacked and, with Romans pressing from two sides, the Aquitani are forced to surrender with heavy casualties. When news of this defeat spreads, the majority of the tribes of Aquitania surrender to Crassus, including the Ausci, Bigerriones, Cocosates, Elusates, Garites, Garumni, Preciani, Suburates, Tarbelli, Tarusates, and 'Vocasates' (and presumably the unmentioned Oscidates). Now only the Morini and Menapii remain in opposition to Rome, never having sent their ambassadors to agree peace terms. Caesar leads his army to their territory but they withdraw into the forests and marshes, having realised that head-on conflict will be fruitless. However, guerrilla warfare simply results in the Romans decimating the countryside and burning the villages, and the invaders return to winter quarters amongst the Aulerci and Lexovii and other recently conquered tribes, having seen off the latest threat.  This artist's impression depicts a selection of Celtiberian Carpetani warriors in various designs of armour and costume, some bearing influences which are Carthaginian or Roman This artist's impression depicts a selection of Celtiberian Carpetani warriors in various designs of armour and costume, some bearing influences which are Carthaginian or Roman |

|

| 55 BC |

As recorded by Julius Caesar in his work, Commentarii de Bello Gallico, the Germanic Tencteri and Usipetes tribes cross the Rhine from Germania and attack first the Belgic Menapii and then the Condrusi and Eburones. The tribes of the Caerosi, Condrusi, Eburones, and Paemani are Belgic peoples who are sometimes thought by scholars to be Germanic, although much of the evidence seems to suggest that they are either Celts, or are ruled by a Celtic nobility. |

It has been suggested (by Rübekeil) that the Tencteri name could be Germanic or Celtic, meaning 'the faithful' in both tongues, but while Julius Caesar calls them Germans, simply because they had come from the eastern side of the Rhine, it seems that both they and the Usipetes had originally belonged, culturally, to the La Tène, making them Celts, or possibly now Celts with a Germanic warrior elite commanding them. The Ambivariti are mentioned only once, by Julius Caesar, and then only vaguely. Their location is not given except by association with the Menapii, to whom they seem to be neighbours. This is in connection with a raid on them by Germans in 55 BC, at which time they are probably based between modern Breda and Antwerp. Thereafter they disappear from history, not to be mentioned by any other classical writer.  This romanticised illustration of Germanic warriors bore little similarity to the rough and ready warriors of the Germanic tribes along the Rhine This romanticised illustration of Germanic warriors bore little similarity to the rough and ready warriors of the Germanic tribes along the Rhine |

|

| 54 BC |

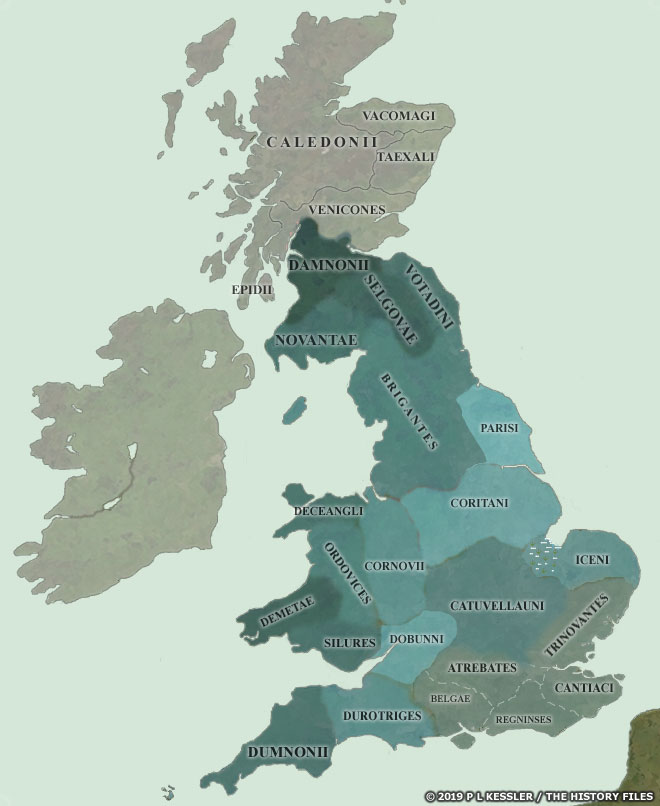

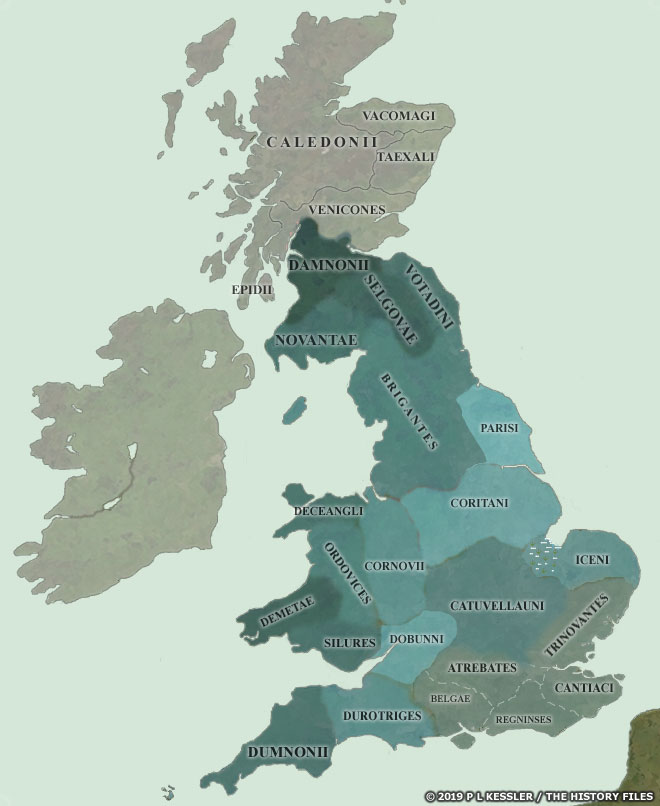

Julius Caesar starts the year by visiting Illyricum to put down incursions by the Pirustae. He raises a local force which readies itself to repel the invaders, forcing the Pirustae to negotiate a peace. From there, he returns to Gaul and assembles a fleet at Port Itius, intent on a second expedition to Britain. Before leaving, he visits the Treveri with four legions, as an internal power struggle has developed between Cingetorix, who is pro-Roman, and Indutiomarus, who opposes him. Indutiomarus persuades his people to join the revolt led by Ambiorix of the Eburones, and declares Cingetorix to be an enemy of the tribe. His property is duly confiscated. The Treveri and their allies manage to defeat a Roman legion during the revolt, but Cingetorix presents himself to Caesar's legate, Titus Labienus, who defeats and kills Indutiomarus in a cavalry engagement. Cingetorix is forced upon the tribe as its new ruler, with the result that leading groups of Treveri apparently cross the Rhine and settle amongst the Germanic tribes there. Returning to Port Itius, Caesar discovers that forty ships which had been built in the country of the 'Meldi' had been driven back by a storm and have returned to port. Caesar intends to take with him most of the Gallic leaders, but Dumnorix of the Aeduii attempts to flee the Roman camp before he can be embarked. He is pursued and cut down. The expedition to Britain goes ahead, bringing Caesar into contact with the Insular Atrebates, Cantii, Catuvellauni, and Trinovantes. Following his return, he is forced to winter his troops in different quarters in Gaul owing to the poor harvests of that year.  By the end of the first century BC and the start of the first century AD, British politics often came to the attention of Rome, and the borders of the tribal states of the south-east were pretty well known (click or tap on map to view full sized) By the end of the first century BC and the start of the first century AD, British politics often came to the attention of Rome, and the borders of the tribal states of the south-east were pretty well known (click or tap on map to view full sized) |

One legion is given to Caius Fabius to be quartered in the territories of the Morini, while Quintus Cicero takes another to the Nervii, Lucius Roscius takes one to the lands of the Essui, and Titus Labienus goes to the Remi 'in the confines of the Treveri'. Three more legions are stationed amongst the Belgae and one with the Eburones who are commanded by Ambiorix and Cativolcus. The recent assassination of Tasgetius of the Carnutes, born of very high rank and a descendant of chiefs of the tribe, raises the fear in the Romans that the tribe will revolt. Lucius Plancus takes a legion to winter amongst them, but his investigations into the murder are interrupted. About fifteen days after the legions enter winter quarters, Ambiorix and Cativolcus of the Eburones instigate the feared revolt, prompted primarily by pressure from their people. A legion under Quintus Titurius Sabinus and Lucius Aurunculeius Cotta is defeated, with both generals being killed and the survivors committing suicide in their fort to avoid capture. Only a few men escape to relate the news to Caesar. Ambiorix marches his cavalry to the Atuatuci, with the infantry following on. The Atuatuci are roused by tales of his victory and then so are the Nervii. Together they launch an attack on the legion of Cicero, razing much of his fort and hard-pressing the defenders.  This print of Ambiorix, king of the Eburones, is inspired by his statue of 1866 in Tongeren in Belgium, with both statue and print reflecting the nineteenth century revival of the Celts in the young Belgian nation state This print of Ambiorix, king of the Eburones, is inspired by his statue of 1866 in Tongeren in Belgium, with both statue and print reflecting the nineteenth century revival of the Celts in the young Belgian nation state |

|

Word of this reaches Marcus Crassus amongst the Bellovaci, just twenty-five miles away, and Caius Fabius also marches from the lands of the Morini, with both forces having to negotiate their way through the lands of the continental Atrebates along the way. Caesar arrives to relieve Cicero and is attacked by about sixty thousand Gauls. Despite the massive disparity in numbers compared to Caesar's own seven thousand, the Gauls are put to flight with great losses, although the Romans suffer casualties of ten percent. Although the situation is calmed by this victory, Cavarinus of the Senones is condemned to death by his people and is forced to flee to the Romans for protection. This serves as a commitment by the tribe to oppose Julius Caesar during his Gallic campaigns. His replacement at the time is unknown, but within three years the tribe is being led by Drappes. The act seems to rally support from amongst most of the Gauls, except the Aeduii and Remi, who remain loyal to Rome, although the Gauls are unable to encourage the Germans to cross the Rhine and support them due to the recent defeats of Ariovistus of the Suevi and of the Tencteri expedition, something which has dissuaded them from a third attempt. However, following the death of Indutiomarus of the Treveri, no further action is taken against the Romans in this year.  Organising the various tribes of Gaul into a unified resistance took some doing, but Vercingetorix of the Arverni appears to have held a level of authority which made him a leader not to be refused, and thousands of warriors flocked to join him Organising the various tribes of Gaul into a unified resistance took some doing, but Vercingetorix of the Arverni appears to have held a level of authority which made him a leader not to be refused, and thousands of warriors flocked to join him |

|

| 53 BC |

Having left a strong guard with the Treveri following the conclusion of their revolt, Caesar again crosses the Rhine to deal with their Germanic supporters. The Ubii reaffirm their loyalty to him while Caesar discovers that those auxiliaries who had joined the Treveri had been sent by the Suevi. They are drawing together units of infantry and cavalry from all across their vast domain and, having learned of Caesar's approach, they withdraw to the vast wood called Bacenis (a thick forest of beech trees which has been equated with the Harz), which separates the Suevi from the Cherusci. Unwilling to follow them, Caesar fortifies the bridge which connects to the Ubii and stations twelve cohorts there. Caesar then enters the country of the Eburones, supported by a contingent of Senones cavalry led by the exiled Cavarinus, their former puppet king. Despite having the cavalry of the Treveri in support, the rebellious Ambiorix flees before the Romans and Cativolcus commits suicide by poisoning. Despite this apparent capitulation, the country of the Eburones proves difficult for the Romans, being woody and swampy in parts. Caesar invites the neighbouring people to come and plunder the tribe and, after stubborn resistance, Caesar burns every village and building which he can find in their territory, drives off all the cattle, and confiscates all of the tribe's grain. The Germanic Sicambri take the opportunity to cross the Rhine and surprise many of the plunderers, seizing a large part of the Eburones' cattle. The Eburones are destroyed by this action and no further mention is made of them in history. Their land is occupied by the Tungri.  This vast map covers just about all possible tribes which were documented in the first centuries BC and AD, mostly by the Romans and Greeks, and with an especial focus on 52 BC (click or tap on map to view at an intermediate size) This vast map covers just about all possible tribes which were documented in the first centuries BC and AD, mostly by the Romans and Greeks, and with an especial focus on 52 BC (click or tap on map to view at an intermediate size) |

The Sicambri, emboldened by their sudden gains, are easily persuaded to attack the main Roman camp with the promise of further riches and little opposition from the small garrison and a large number of invalids. After being surprised, the Roman defenders manage to rally under Sextus Baculus. They are reinforced by the returning foraging party and the Sicambri withdraw, seeing that they will not now prevail. They withdraw across the Rhine with their plunder and Caesar is able to settle his men into winter quarters. However, greater events are afoot. On 13 February 53 BC the disaffected Carnutes had massacred every Roman merchant who had been present in the town of Cenabum, as well as killing one of Caesar's commissariat officers. This is the spark which ignites a massed Gaulish rebellion. While Julius Caesar has been occupied in the lands of the Belgae, Vercingetorix has renewed the Arverni subjugation of the Aeduii. He has also restored the reputation of Arverni greatness by leading the revolt which is building against Rome. Despite his former allegiance to Julius Caesar, in the winter of 53-52 BC Commius of the Atrebates uses his contacts with the Bellovaci to convince them to contribute two thousand men to an army. This army will join other Gauls to form a massive relief force at Alesia in the last stage of the revolt.  Both sides of a coin issued by the Atrebates between 50-20 BC, either in the name of Commius or his son despite their evacuation to Britain around 50 BC Both sides of a coin issued by the Atrebates between 50-20 BC, either in the name of Commius or his son despite their evacuation to Britain around 50 BC |

|

| The Lemovices are also amongst the first tribes to commit to joining Vercingetorix, contributing ten thousand men. The Mediomatrici send five thousand men, and the Andes, Ruteni, and Turones are also amongst the first to commit. The warriors of the Pictones decide to supply eight thousand warriors but their chief, Duratios, stands firm in his desire to maintain his alliance with Rome, and this difference of opinion causes a split in the tribe. The warriors join the chief of the Andes who heads for Lemonum to besiege Duratios. The king sends a messenger to the Roman legate, Caius Caninius, who comes to his aid from the territory of the Ruteni. This small force is soon backed up by a more effective unit under Caius Fabius and a Pictonii civil war is averted. |

|

| 52 BC |

The Aulerci, Cadurci, Lemovices, Parisii, Pictones, Senones, and Turones have all joined Vercingetorix of the Arverni, as do all of the tribes which border the ocean. The Treveri support the revolt but are pinned down by Germanic tribes. Vercingetorix sends Lucterius of the Cadurci into the territory of the Ruteni to gain their support, and marches in person to the Bituriges. The latter, under the protection of the Aeduii, send to them for help to resist the Arverni but are forced to join the revolt. Lucterius continues to the Gabali and Nitiobroges and wins their support, collecting together a large force ahead of an advance into the province of Narbonensis.  Lemonum (modern Potiers) was the chief tribal settlement of the Pictones Celts in first century BC Gaul, while today's Amphoralis Museum provides a glimpse of life in pre-Roman France Lemonum (modern Potiers) was the chief tribal settlement of the Pictones Celts in first century BC Gaul, while today's Amphoralis Museum provides a glimpse of life in pre-Roman France |

Caesar gets there first and rallies the garrisons among the Ruteni and Volcae Arecomisci, and Lucterius is forced to retreat. From there Caesar circles through the territory of the generally pro-Roman Helvii (who provide auxiliaries) to reach that of the Arverni, despite deep winter snows in the mountains. Vercingetorix, after sustaining a series of losses at Vellaunodunum, Genabum, and Noviodunum, summons his men to a council in which it is decided that the Romans should be prevented from being able to gather supplies. A scorched earth policy is adopted, and more than twenty towns of the Bituriges are burned in one day, although their oppidum at Avaricum is spared. The Boii have little with which to support the Romans, and the Aeduii are showing little enthusiasm for it, but Caesar secures all the supplies he needs when he besieges and storms Avaricum, despite a formidable Gaulish defence. From there, the two sides gravitate towards an eventual confrontation at Gergovia, a town of the recently resettled Boii. Now the chief of the generally pro-Roman Aeduii, Convictolitavis, is free to end his equivocation and leads a force not in support of Caesar at Gergovia but against him. The Nitiobroges also send troops to aid Vercingetorix there. Caesar loses the siege after having to split his forces to face the unexpected threat, a rare defeat for him in Gaul.  The site of Alesia, a major fort belonging to the Mandubii tribe of Celts, was the scene of the final desperate stand-off between Rome and the Gauls in 52 BC The site of Alesia, a major fort belonging to the Mandubii tribe of Celts, was the scene of the final desperate stand-off between Rome and the Gauls in 52 BC |

|

Labienus marches with four legions to the Parisii town of Lutetia. Gauls from the neighbouring states immediately gather to oppose him, under the leadership of the aged but still very wise Camulogenus of the Aulerci. Labienus pulls back to Melodunum of the Senones, takes the town by force, and marches again against Camulogenus. The ensuing battle sees the Gauls defeated and Camulogenus killed. Labienus joins Caesar while Vercingetorix levies troops from the Aeduii and Segusiavi. These he places under the command of the brother of Eporedirix and orders them to attack the Allobroges. The Gabali and the easternmost Arverni cantons are sent to fight the Helvii, and the Cadurci and Ruteni are told to lay waste the territories of the Volcae Arecomisci. The Helvii are defeated and their leaders slain, including Caius Valerius Donotaurus, the son of Caburus. The Allobroges manage to defend their frontiers successfully, but Caesar finds that he is hard-pressed to counter Vercingetorix's superiority in cavalry. He calls for cavalry and light infantry from the loyal Germanic tribes (which undoubtedly includes the Ubii), and this helps him greatly in the battle which follows.  The Vercingetorix monument was created by the sculptor, Aimé Millet, and was installed in 1865 on Mont Auxois in France The Vercingetorix monument was created by the sculptor, Aimé Millet, and was installed in 1865 on Mont Auxois in France |

|

Vercingetorix, his cavalry routed in that battle, withdraws in good order to Alesia, a major fort belonging to the Mandubii. The remaining cavalry are dispatched back to their tribes to bring reinforcements. Caesar begins a siege of Alesia, aiming on starving out the inhabitants. Indeed, matters become so bad inside the fort that the Mandubian women and children are ejected (possibly in the hope that the Roman lines will part to let them pass), but Caesar effectively traps them in the no-man's-land between the opposing forces and allows them to starve. Four relief forces amounting to a considerable number of men and horses are assembled in the territory of the Aeduii by the council of the Gaulish nobility. Demanded from the tribes of Gaul are thirty-five thousand men from the Aeduii and their dependents, the Ambivareti, Brannovices, and Segusiavi; an equal number from the Arverni in conjunction with the Cadurci, Eleuteti, Gabali, and Vellavi, who are accustomed to following Arverni commands; twelve thousand each from the Bituriges, Carnutes, Ruteni (mostly archers), Santones, Senones, and Sequani; ten thousand each from the Bellovaci, Helvetii and Lingones; eight thousand each from the Helvii (despite the tribe's pro-Roman standing), Parisii, Pictones, and Turones; six thousand combined from the tribes of Armorica (including the Ambibari, Caleti, Cariosvelites, Lemovices, Osismii, Redones, Venelli, Veneti); five thousand each from the Ambiani, Mediomatrici, Morini, Nervii, Nitiobroges, Petrocorii, and Suessiones; the same number from the Aulerci Cenomani; four thousand from the Atrebates; three thousand each from the Aulerci Eburovices, Bellocassi, Lexovii, and Veliocasses; plus substantial numbers sent by the Boii and Raurici.  Gaulish warriors were characterised by their longswords and decorated shields, with many even fighting naked, but Rome's military machine was tougher and better resourced Gaulish warriors were characterised by their longswords and decorated shields, with many even fighting naked, but Rome's military machine was tougher and better resourced |

|

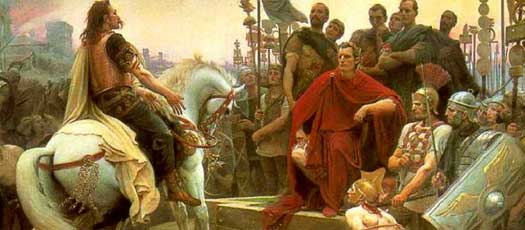

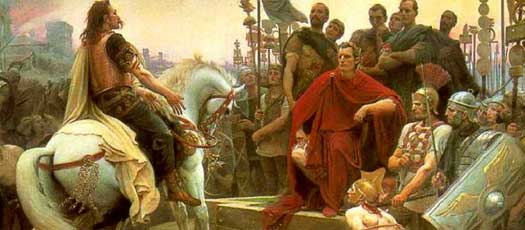

Of all of these the Bellovaci withhold their contribution, claiming that they would wage war against the Romans on their own account, free of external command. However, at the request of Commius of the Atrebates, they send two thousand men in consideration of a tie of hospitality which exists between them and him. Commanders are appointed, one of which is Vercassivellaunos, who teams up with Sedullos of the Lemovices. Together they attempt to relieve Vercingetorix at the siege of Alesia, but the combined relief force is soundly repulsed by Julius Caesar's remarkable strategy of simultaneously conducting the siege of Alesia on one front whilst being besieged on the other. Marcus Antonius (Mark Anthony) and Caius Trebonius marshal the troops for the rearward defence. Sedullos of the Lemovices is slain, and Vergasillaunus of the Arverni is captured. Seeing that all is lost, Vercingetorix surrenders to Caesar. The garrison is taken prisoner, as are the survivors from the relief army. They are either sold into slavery or given as booty to Caesar's legionaries, apart from the Aeduii and Arverni warriors who are released and pardoned in order to secure the allegiance of these important and powerful tribes.  Having surrendered with honour to Caesar in 52 BC, Vercingetorix remained a potent symbol of resistance to Roman domination, so his murder in 46 BC dealt a terminal blow to hopes of renewed Celtic freedom Having surrendered with honour to Caesar in 52 BC, Vercingetorix remained a potent symbol of resistance to Roman domination, so his murder in 46 BC dealt a terminal blow to hopes of renewed Celtic freedom |

|

| During the revolt, the Bituriges Cubi fall back to their main oppidum of Avaricum. Although they put up a desperate resistance, their hill fort ultimately falls to a Roman assault and all its surviving inhabitants are put to the sword. The Carnutes make their own situation worse by attacking the Bituriges Cubi, whom Caesar aids. As a reminder of their part in the rebellion, the Carnutes town of Cenabum is left in ruins and the location is garrisoned by two Roman legions. Vercingetorix is imprisoned in the Tullianum in Rome for five years and the western Gaulish lands fall to the republic to be incorporated into the Roman province of Gaul. Following the surrender of Alesia, Commius of the Atrebates returns north and joins Correus of the Bellovaci. The two men command the last major Gaulish army to directly oppose Caesar, and for some time they manage to hold off the Romans until defeat finally ends their resistance. |

|

|

|

The system which has evolved to catalogue the various archaeological expressions of human progress is one which involves cultures. For well over a century, archaeological cultures have remained the framework for global prehistory. The earliest cultures which emerge from Africa and the Near East are perhaps the easiest to catalogue, right up until human expansion reaches the Americas. The task of cataloguing that vast range of human cultures is covered in the related feature (see feature link, right).

The system which has evolved to catalogue the various archaeological expressions of human progress is one which involves cultures. For well over a century, archaeological cultures have remained the framework for global prehistory. The earliest cultures which emerge from Africa and the Near East are perhaps the easiest to catalogue, right up until human expansion reaches the Americas. The task of cataloguing that vast range of human cultures is covered in the related feature (see feature link, right).  It seems highly likely from detailed analysis that the first wave of Indo-European-speaking peoples to arrive in Western Europe were members of the West Indo-European proto-Italic branch. They displaced - and more often incorporated - early inhabitants who appear physically to have been Mediterranean prehistoric folk who spoke non-Indo-European languages from the Dene-Caucasian language group (see index link for a list of early cultures). Into this mix was added the proto-Celtic Urnfield culture which greatly expanded Indo-European influence across many regions of Europe which previously had been populated entirely by indigenous Mesolithic or later-arriving Neolithic groups. The Urnfield was directly succeeded by the Hallstatt culture, the first truly Celtic culture. This expanded outwards to fill much of the territory between modern France and Hungary, ancient Iberia, Germania, and Bohemia, and ancient Britain and the Anatolia of the Galatians. This expansion continued for about four hundred years before it expended itself, but it was immediately succeeded by its own offspring, the La Tène culture. This 'second wave' of Celts was made up of P-Celtic speakers who very quickly followed the (almost certainly unbroken) migratory trail to settle in areas which later became known as Gaul, and all points east. How the language shift occurred in the Celtic homeland between the Hallstatt and the La Tène is the subject of quite a bit of speculation. Overall, it seems most likely that they were heavily influenced by Indo-European migrants who were moving into the region between the eighth and fifth centuries BC by following the Danube from the western shore of the Black Sea.

It seems highly likely from detailed analysis that the first wave of Indo-European-speaking peoples to arrive in Western Europe were members of the West Indo-European proto-Italic branch. They displaced - and more often incorporated - early inhabitants who appear physically to have been Mediterranean prehistoric folk who spoke non-Indo-European languages from the Dene-Caucasian language group (see index link for a list of early cultures). Into this mix was added the proto-Celtic Urnfield culture which greatly expanded Indo-European influence across many regions of Europe which previously had been populated entirely by indigenous Mesolithic or later-arriving Neolithic groups. The Urnfield was directly succeeded by the Hallstatt culture, the first truly Celtic culture. This expanded outwards to fill much of the territory between modern France and Hungary, ancient Iberia, Germania, and Bohemia, and ancient Britain and the Anatolia of the Galatians. This expansion continued for about four hundred years before it expended itself, but it was immediately succeeded by its own offspring, the La Tène culture. This 'second wave' of Celts was made up of P-Celtic speakers who very quickly followed the (almost certainly unbroken) migratory trail to settle in areas which later became known as Gaul, and all points east. How the language shift occurred in the Celtic homeland between the Hallstatt and the La Tène is the subject of quite a bit of speculation. Overall, it seems most likely that they were heavily influenced by Indo-European migrants who were moving into the region between the eighth and fifth centuries BC by following the Danube from the western shore of the Black Sea.  Archaeology has supported such a migratory influx prior to the advent of the La Tène. These groups who entered the Celtic heartland were perhaps Thraco-Cimmerians (controversially, perhaps - see feature link), or at least neighbouring groups which were influenced by them through a process of cultural osmosis. At the very least, newly-arriving Indo-European groups in the Celtic heartland in today's Switzerland and southern Germany shared the same cultural values, and martial equipment - and probably language too - as the Thracians and Cimmerians, and even Scythians, and it seems to have been they who introduced these changes into that Celtic core to produce the La Tène.

Archaeology has supported such a migratory influx prior to the advent of the La Tène. These groups who entered the Celtic heartland were perhaps Thraco-Cimmerians (controversially, perhaps - see feature link), or at least neighbouring groups which were influenced by them through a process of cultural osmosis. At the very least, newly-arriving Indo-European groups in the Celtic heartland in today's Switzerland and southern Germany shared the same cultural values, and martial equipment - and probably language too - as the Thracians and Cimmerians, and even Scythians, and it seems to have been they who introduced these changes into that Celtic core to produce the La Tène.  In time, the La Tène Celts expanded outwards to enter much the same territory as their Hallstatt forebears. In Gaul, they found themselves divided by the rivers Marne and Seine from the Belgae who were similarly settling to their north, and from the indigenous Aquitani to the south by the River Garonne (see map link for tribal locations). Those groups which entered Iberia appear to have arrived by boat to settle the northern and western coasts, such as the tribes of the Astures and Gallaeci. The majority of these Celts were Gauls, a broad definition of western and Central European Celts which was so well known by Rome. The Romans coined the name 'Galli' ('roosters or cockerels') to describe Celtic tribesmen in general, and this was especially applied to the tribes of what is now central, northern, and eastern France and, to an extent, those in Germany too.

In time, the La Tène Celts expanded outwards to enter much the same territory as their Hallstatt forebears. In Gaul, they found themselves divided by the rivers Marne and Seine from the Belgae who were similarly settling to their north, and from the indigenous Aquitani to the south by the River Garonne (see map link for tribal locations). Those groups which entered Iberia appear to have arrived by boat to settle the northern and western coasts, such as the tribes of the Astures and Gallaeci. The majority of these Celts were Gauls, a broad definition of western and Central European Celts which was so well known by Rome. The Romans coined the name 'Galli' ('roosters or cockerels') to describe Celtic tribesmen in general, and this was especially applied to the tribes of what is now central, northern, and eastern France and, to an extent, those in Germany too.  From this was derived the name 'Gaul'. Julius Caesar in his commentaries reported that they called themselves 'Celtae', but they could also be recorded as 'galat', and there are three regions in Europe today which still bear this name of Galatia (from 'galat'). Linguistics theory points to a common origin for both forms of the name, along with the German version, 'wealas' or 'wahl' (see feature link for more on this). These Gauls (Celts) dominated much of western and Central Europe in their heyday but, by the middle of the first century BC they had become fragmented, and were either in the process of being expelled from Germania by the increasingly powerful Germanic tribes which were migrating southwards from Scandinavia and the Baltic coast, or they were being defeated and integrated into Germanic or other tribes, or they were being conquered by Rome. To an extent this 'second wave' of Celts post-dates the earliest movements of the 'third wave', that of the Belgae. However, the latter only entered the northern limits of Gaul around the fourth or third centuries BC at the earliest, perhaps a century or so after the La Tène Celts arrive there, so the established order stands for each of the waves of migration.

From this was derived the name 'Gaul'. Julius Caesar in his commentaries reported that they called themselves 'Celtae', but they could also be recorded as 'galat', and there are three regions in Europe today which still bear this name of Galatia (from 'galat'). Linguistics theory points to a common origin for both forms of the name, along with the German version, 'wealas' or 'wahl' (see feature link for more on this). These Gauls (Celts) dominated much of western and Central Europe in their heyday but, by the middle of the first century BC they had become fragmented, and were either in the process of being expelled from Germania by the increasingly powerful Germanic tribes which were migrating southwards from Scandinavia and the Baltic coast, or they were being defeated and integrated into Germanic or other tribes, or they were being conquered by Rome. To an extent this 'second wave' of Celts post-dates the earliest movements of the 'third wave', that of the Belgae. However, the latter only entered the northern limits of Gaul around the fourth or third centuries BC at the earliest, perhaps a century or so after the La Tène Celts arrive there, so the established order stands for each of the waves of migration.  Archaeological finds are constantly being made, and archaeological cultures are frequently being updated with new information. Get in touch here if this page also requires updating.

Archaeological finds are constantly being made, and archaeological cultures are frequently being updated with new information. Get in touch here if this page also requires updating.

Belgic settlement in, or migration across, Northern Europe almost certainly involved some of them entering the Cimbric peninsula where they interacted with early German tribes there, influencing them and being influenced by them

Belgic settlement in, or migration across, Northern Europe almost certainly involved some of them entering the Cimbric peninsula where they interacted with early German tribes there, influencing them and being influenced by them By around 3000 BC the Indo-Europeans had begun their mass migration away from the Pontic-Caspian steppe, with the bulk of them heading westwards towards the heartland of Europe (click or tap on map to view full sized)

By around 3000 BC the Indo-Europeans had begun their mass migration away from the Pontic-Caspian steppe, with the bulk of them heading westwards towards the heartland of Europe (click or tap on map to view full sized) The Riesengebirge was part of the once-vast Hercynian Forest which spread eastwards from southern Germany and which proved a serious impediment to Roman expansion

The Riesengebirge was part of the once-vast Hercynian Forest which spread eastwards from southern Germany and which proved a serious impediment to Roman expansion Pytheas of Massalia undertakes a voyage of exploration to north-western Europe, becoming the first scholar to note details about the Celtic and Germanic tribes there (see feature link). One of the tribes he records is the Ostinioi - almost certainly the Osismii - who occupy Cape Kabaïon, which is probably pointe de Penmarc'h or pointe du Raz in western Armorica. This means that the tribe has already settled the region by the mid-fourth century, probably alongside their neighbours of later years, the Veneti, Cariosvelites, and Redones.