|

|

| (Information by Peter Kessler and Edward Dawson, with additional information from The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World, David W Anthony, from The Iliad, Homer (Translated by E V Rieu, Penguin Books, 1963), from Europe Before History, Kristian Kristiansen, from A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, William Smith (Ed), from An Historical Geography of Europe, Norman J G Pounds (Abridged Version), from History of Humanity - Scientific and Cultural Development: From the Third Millennium to the Seventh Century BC (Vol II), Ahmad Hasan Dani, Jean-Pierre Mohen, J L Lorenzo, & V M Masson (Unesco 1996), and from External Links: Haplogroup R1a (Eupedia Genetics), and DNA clue to origins of early Greek civilization (BBC News), and Grave of the Griffin Warrior, and The Greeks really do have near-mythical origins, ancient DNA reveals (Science).) |

|

| c.3000 - 2800 BC |

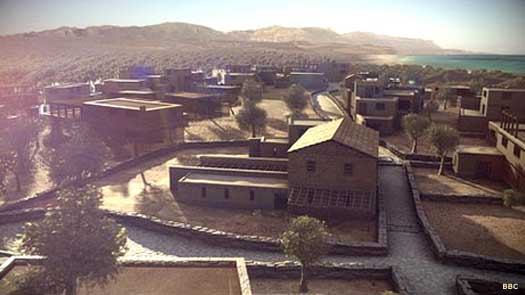

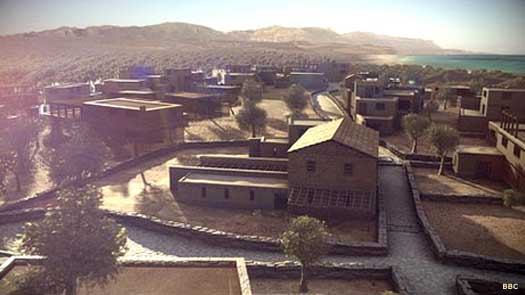

Preceding the arrival of the Mycenaeans by a good millennium or so, the city of Pavlopetri is founded on the south-eastern coastal tip of the Peloponnese, in southern Laconia. Pavlopetri's inhabitants later copy Cretan and mainland styles, making exact ceramic copies of high status Cretan bronze jugs, in effect making cheap copies of expensive exotic goods in much the same way that desirable designer brands are copied today.  Modern computer graphics show a reconstructed Pavlopetri based on surviving ruins and remnants of the street plan, all of which still exist about three metres under the sea Modern computer graphics show a reconstructed Pavlopetri based on surviving ruins and remnants of the street plan, all of which still exist about three metres under the sea |

| But the early city is not a Minoan colony, and certainly not a Mycenaean settlement. It predates both peoples in the area, making it more likely to be a Pelasgian settlement which is later subject to heavy Minoan influence or control in the second millennium BC, and then is absorbed into Mycenaean society. The city flourishes, reaching a peak around 2000 BC. |

|

| c.2600 BC |

This is a tentative dating for the earliest members of Greek mythology where it relates to kings of the Mycenaeans. Pandion II is the mythical ruler of Athens and father to Lycus of Lycia and Aegeus of Athens (albeit with much later dating in relation to Athens itself). Given the links between Aegeus and Medea, Pandion (if he exists at all) is more likely to be a thirteenth century BC king, someone who is either mistaken for an earlier king or whose dating is incorrect. By any reckoning, the Mycenaeans of this time are still steppe nomads.  By around 3000 BC the Indo-Europeans had begun their mass migration away from the Pontic-Caspian steppe, with the bulk of them heading westwards towards the heartland of Europe (click or tap on map to view full sized) By around 3000 BC the Indo-Europeans had begun their mass migration away from the Pontic-Caspian steppe, with the bulk of them heading westwards towards the heartland of Europe (click or tap on map to view full sized) |

| c.2000 BC |

Now at its height, the city of Pavlopetri contains detached and semi-detached two-storey houses with gardens, walls, and well-made streets, and clothes drying in the courtyards. There are larger, apparently public buildings and evidence of a complex water management system involving channels and guttering. The city is divided into pleasant courtyards and open areas in which people cultivate gardens, ground grain, dry clothes, and probably even chat with their neighbours. Dotted between the buildings and sometimes built into the walls themselves are stone-lined graves. These contrast with an organised cemetery just outside the city. This is not the more basic village of Neolithic farmers but a stratified society in which people have professions - city leaders, officials, scribes, merchants, traders, craftsmen (potters, bronze workers, artists), soldiers, sailors, farmers, shepherds, and also probably slaves - all echoing the early hierarchical and organised aspects of Bronze Age Greece. Pavlopetri is now heavily influenced by the regionally-dominant Minoan culture. |

| c.1900 - 1650 BC |

Now having left the steppe and arriving on the west bank of the River Prut (generally speaking, the modern border between Romania and Moldova), the proto-Mycenaeans likely meet other, closely related Indo-European groups of the South-West Indo-European branch between there and the eastern side of the Carpathian Mountains.  The proto-Mycenaeans seem to have been amongst the last of the western Indo-European _centum_-speakers to take to the road, following a path which had been trodden by related tribes for the past thousand years (click or tap on map to view full sized) The proto-Mycenaeans seem to have been amongst the last of the western Indo-European _centum_-speakers to take to the road, following a path which had been trodden by related tribes for the past thousand years (click or tap on map to view full sized) |

| Similar groups would already be lining the Danube through Romania and into Hungary. They may even have begun to fan out into what is now northern Serbia and Croatia, although a belt of much more difficult terrain beyond that, in line with the Balkans Mountains which cut horizontally through Bulgaria, would inhibit any further southwards drift for some time. It is likely that, rather than settle with related Indo-European groups along the Danube or in Romania, the proto-Mycenaeans keep moving, descending into what is now Greece (the modern E4 walking route along the western edge of Romania and through Bulgaria offers one potential path of least resistance through the mountains). There they intermingle with and dominate the Neolithic locals of the former farming cultures of 'Old Europe' to create a new, unique Greek culture. Naturally, as the new dominant force in the region, their language also dominates. |

|

| c.1600 BC |

Mycenaean culture appears on Cyprus, gradually displacing Minoan culture. Mycenaean shaft graves dated to this early period clearly demonstrate their dominance on the Greek mainland. At the same time, the people of the Central European Unetice culture establish commercial relations with the Mycenaeans.  The necropolis at Karmi shows Bronze Age Cyprus at the height of its fortunes, with more powerful and rewarding international trade routes than ever before The necropolis at Karmi shows Bronze Age Cyprus at the height of its fortunes, with more powerful and rewarding international trade routes than ever before |

| A transcontinental amber trade has already begun at about the same time as the Baltic Bronze Age, and amber has already been in some demand by the Uneticians themselves. Now, though, the amber trade reaches an amazing volume. The Uneticians import their amber from the Balts and from the Germanic peoples in Jutland. It has been estimated that at least eighty percent of the graves of classical Unetice contain amber beads. |

|

| c.1500 BC |

The 'Griffin Warrior' dies in this period and is buried alone near the site of the later 'Palace of Nestor' at Pylos. His burial is accompanied by one of the most magnificent displays of wealth ever to be discovered in Greece by twenty-first century AD archaeologists. The character of those objects which follow him into the afterlife - no ceramics but plenty of bronze, silver, and gold - prove that this part of Greece, like the city state of Mycenae itself, is being indelibly shaped by close contact with the Minoans. This warrior, clearly a ruler in the Pylos region, has lived on the acropolis of Englianos at a time at which mansions are first being built with walls of cut-stone blocks, in the so-called Minoan ashlar style.  Shown here are some of those finds which have been discovered in the lowest levels of the Griffin Warrior's tomb, amongst which are a blade, 'horns', and part of the hilt of a Minoan-type sword, lying on top of a bronze short sword with a similar gold handle Shown here are some of those finds which have been discovered in the lowest levels of the Griffin Warrior's tomb, amongst which are a blade, 'horns', and part of the hilt of a Minoan-type sword, lying on top of a bronze short sword with a similar gold handle |

| c.1470 BC |

During this period, Greece is still under the domination of the Minoans, but the volcano at the heart of the island of Thera erupts around this time, catastrophically ending Minoan dominance of the Mycenaeans. The various Mycenaean city states begin in turn to dominate not only Greece but the islands of the Aegean and Minoan Crete itself. The states of Iolkos and Mycenae both rise to prominence at this time, as do the semi-mythical early Thracians. |

| c.1450 BC |

The Bronze Age kingdom of Ahhiyawa first becomes prominent on the Aegean coast of Anatolia, being mentioned in Hittite texts. It remains of minor importance but its rise so soon after the destruction of Minoan dominance is telling. Its main base or capital is Milawata (Millawanda, Classical Miletus) and its people are usually believed to be Mycenaeans.  Whilst this map concentrates principally on neighbouring Arzawa to show a rough estimation of its borders at the kingdom's height, it also clearly shows the approximate location of Ahhiyawa which, if anything, is even more mysterious than the little-recorded Arzawa (click or tap on map to view full sized) Whilst this map concentrates principally on neighbouring Arzawa to show a rough estimation of its borders at the kingdom's height, it also clearly shows the approximate location of Ahhiyawa which, if anything, is even more mysterious than the little-recorded Arzawa (click or tap on map to view full sized) |

| King Minyas has several claims in regard to his parents, most of them related to gods. The only two humans to be involved are Orchomenus, his son, and his wife, Hermippe. In Greek myth, Minyas founds the city of Orchomenus in Boeotia (to the north-west of Athens) after leading his followers from coastal Thessaly. He is also the father of several children, one of which - another Orchomenus - succeeds him in the city which bears his name while another son, Cyparissus, founds Anticyra. |

|

| Orchomenus or Chryses |

Chryses was ruler of the Phlegyans. |

| Minyas |

Son. Founder of Orchomenus in Boeotia. |

| Orchomenus |

Son. |

| c.1400 BC |

Announced in 2017 is the discovery of one of the largest ancient Greek tombs ever discovered. A team of archaeologists working near the Mycenaean city of Orchomenus in Boeotia (the 'Minyan Orchomenus') finds the tomb, containing the body of one man and a trove of artefacts.  The team work on the track which leads to the tomb of the unknown, but very wealthy and well-honoured Mycenaean near the city of Orchomenus in Boeotia in this discovery of one of the richest graves of its type The team work on the track which leads to the tomb of the unknown, but very wealthy and well-honoured Mycenaean near the city of Orchomenus in Boeotia in this discovery of one of the richest graves of its type |

| The burial tomb for this unknown Mycenaean measures a massive 12.8 square metres in size. The collection of grave goods and the tomb's size clearly mark out the occupant as a leading figure in Mycenaean society, and very likely a king - perhaps Orchomenus himself. |

|

| 13th century BC |

Although Mycenaean city states reach the height of their power by the end of the fourteenth century BC, Greek legends and myths provide only enough names to list possible kings as far back as about the early thirteenth century BC. These are the immediate ancestors of the kings who become involved in the Trojan War against the city state of Troy and its allies. This is the one key event in Mycenaean history which solidifies their existence to later generations as anything more than a series of archaeological digs (despite the war being remembered only in oral tradition until Homer writes it down some four hundred or more years later).  This illustration is another artist's impression of an unspecified version of Troy, although it is believed to be based on the city which existed around the time of the Trojan War, shortly before its defeat and destruction This illustration is another artist's impression of an unspecified version of Troy, although it is believed to be based on the city which existed around the time of the Trojan War, shortly before its defeat and destruction |

| Those Mycenaean city states which can confidently be claimed as existing with their own kingship (historical or legendary) include Achaean Crete, Athens, Boeotia, Ephyra, Iolkos, Laconia, Mycenae, Orchomenus, the Phlegyans, and Phthia. |

|

| c.1193 - 1183 BC |

Agamemnon of Mycenae calls to arms the forces of his allied Achaean kingdoms, including Athens, Crete, Ephyra, Laconia, Phthia, Pylos, Tiryns, and Thebes. Before he can leave for the Trojan War, the seer Calchas (later to be found in Pamphylia) prophesises that in order to gain a favourable wind, the king must sacrifice his daughter, Iphigeneia, to the gods. After that unsavoury act, the combined and somewhat fractious force sails off to various adventures on its way to Troy (probably signifying a series of campaigns or raids over several years), leaving Agamemnon's strong-willed wife, Clytemnestra, in charge. |

| 1200 - 1140 BC |

Mycenaean power is gradually eroded by the Dorians who are migrating in from the Balkans, with domination coming by 1140 BC. The surviving Ionic-speaking Mycenaeans gather and flourish in Athens or perhaps in conquered Levantine territories which probably include Phillistia, or in new colonies which have been founded well away from the Dorians.  Climate-induced drought in the thirteenth century BC created great instability in the entire eastern Mediterranean region, resulting in mass migration in the Balkans, as well as the fall of city states and kingdoms further east (click or tap on map to view full sized) Climate-induced drought in the thirteenth century BC created great instability in the entire eastern Mediterranean region, resulting in mass migration in the Balkans, as well as the fall of city states and kingdoms further east (click or tap on map to view full sized) |

These include Epirus in north-western Greece and Pamphylia in Anatolia, but it also seems likely that Mycenaeans form groups within the Sea Peoples who ravage the eastern Mediterranean in this period. All Mycenaean palaces and fortified sites are destroyed and a major proportion of other sites are abandoned. The population of the Peloponnese appears to decline by about seventy-five percent. Mycenae itself remains occupied, but is burned twice in succession and survives in a much-reduced state and size, never again to hold the reins of power. Once the Hittites had been destroyed around 1200 BC, and the Mycenaeans had themselves (probably) smashed Troy, the colonisation of the western coast of Anatolia could begin (the possibility that the earlier Ahhiyawa may also be a Mycenaean colony notwithstanding). This would seem to be the most likely - and popular - avenue of Mycenaean escape from the mainland. Once there they form or take over states or regions such as Caria, Lycia, and [ Maeonia](../KingListsMiddEast/AnatoliaLydia.htm#Heraclid Lydia), and perhaps Pamphylia, between about 1100 to 900 BC. Those states themselves usually survive until they are conquered by the later great empires.  Mycenae was already in ruins by the start of the first millennium AD, having been abandoned during the fall of Mycenaean Greece Mycenae was already in ruins by the start of the first millennium AD, having been abandoned during the fall of Mycenaean Greece |

|

| However, in common with much of the Near East, this general instability which has been driven by a major regional drought causes a dark age to fall throughout the remainder of Greece, until about 750 BC, when early Classical Greece begins to emerge. Overseas trade ceases in the Mediterranean, people are no longer buried with lavish grave goods, and the fortress of Minyan Orchomenus is one of those to be broken by the Dorians, while others are substantially reduced in size or are abandoned altogether. The only state to buck the trend is that of Alashiya, which prospers. In Greece, classical states such as Athens, Corinth, Epirus, Macedonia, Phthia, Sparta, and [Thrace](GreeceThrace.htm#Odrysian Kingdom) slowly emerge (or re-emerge) during the ninth to seventh centuries BC. Many of them do so with a Dorian ruling elite in place over the remaining Mycenaean nobility and the Neolithic general populace. |

|

| c.1000 BC |

The city of Pavlopetri in southern Laconia is submerged beneath about three metres of water, probably by an earthquake. The city's disappearance appears to occur in three stages, with sections of it being abandoned to the water but buildings on higher ground remaining occupied.  This actual footage of the ruins of Pavlopetri on the sea bed has been enhanced with computer-generated images to show the original building in context with the present site This actual footage of the ruins of Pavlopetri on the sea bed has been enhanced with computer-generated images to show the original building in context with the present site |

| Perhaps three successive earthquakes in one of the most geologically active regions of Europe seal the city's fate. Even today, Pavlopetri appears as a series of large areas of stones which indicate building complexes, amongst which can be traced a network of walls. Archaeologists recover the shards of everyday items such as cooking pots, crockery, jugs, storage vessels, and grinding stones, as well as finer drinking vessels which are probably kept to impress, being brought out when higher status guests pay a visit or being used to make offerings to the gods. |

|

|

|

Records covering the Mycenaeans are very sparse, usually being limited to myths and legends. Many of their leaders are semi or wholly legendary (and see feature link for details on leadership ranks). Where they are shown in the lists below and on related pages, legendary leaders are backed in lilac, usually for events prior to the Trojan War and the fall of Troy, an event which itself is barely historical. Mycenaeans also established trading outposts on the Anatolian coast (especially after the fall of Troy). Mycenaeans were possibly the Ahhiyawa who were mentioned in Hittite texts from the mid-fifteenth century BC onwards. Their civilisation seems to have flourished immediately following the fall of the Minoan civilisation, which appears to have dominated them up to that point. DNA research has shown that the Minoans of Crete were generally of the same origin as the Mycenaeans - Neolithic natives overlaid with an Indo-European cultural identity, and both share their DNA with today's Greeks.

Records covering the Mycenaeans are very sparse, usually being limited to myths and legends. Many of their leaders are semi or wholly legendary (and see feature link for details on leadership ranks). Where they are shown in the lists below and on related pages, legendary leaders are backed in lilac, usually for events prior to the Trojan War and the fall of Troy, an event which itself is barely historical. Mycenaeans also established trading outposts on the Anatolian coast (especially after the fall of Troy). Mycenaeans were possibly the Ahhiyawa who were mentioned in Hittite texts from the mid-fifteenth century BC onwards. Their civilisation seems to have flourished immediately following the fall of the Minoan civilisation, which appears to have dominated them up to that point. DNA research has shown that the Minoans of Crete were generally of the same origin as the Mycenaeans - Neolithic natives overlaid with an Indo-European cultural identity, and both share their DNA with today's Greeks.

Modern computer graphics show a reconstructed Pavlopetri based on surviving ruins and remnants of the street plan, all of which still exist about three metres under the sea

Modern computer graphics show a reconstructed Pavlopetri based on surviving ruins and remnants of the street plan, all of which still exist about three metres under the sea By around 3000 BC the Indo-Europeans had begun their mass migration away from the Pontic-Caspian steppe, with the bulk of them heading westwards towards the heartland of Europe (click or tap on map to view full sized)

By around 3000 BC the Indo-Europeans had begun their mass migration away from the Pontic-Caspian steppe, with the bulk of them heading westwards towards the heartland of Europe (click or tap on map to view full sized) The proto-Mycenaeans seem to have been amongst the last of the western Indo-European _centum_-speakers to take to the road, following a path which had been trodden by related tribes for the past thousand years (click or tap on map to view full sized)

The proto-Mycenaeans seem to have been amongst the last of the western Indo-European _centum_-speakers to take to the road, following a path which had been trodden by related tribes for the past thousand years (click or tap on map to view full sized) The necropolis at Karmi shows Bronze Age Cyprus at the height of its fortunes, with more powerful and rewarding international trade routes than ever before

The necropolis at Karmi shows Bronze Age Cyprus at the height of its fortunes, with more powerful and rewarding international trade routes than ever before Shown here are some of those finds which have been discovered in the lowest levels of the Griffin Warrior's tomb, amongst which are a blade, 'horns', and part of the hilt of a Minoan-type sword, lying on top of a bronze short sword with a similar gold handle

Shown here are some of those finds which have been discovered in the lowest levels of the Griffin Warrior's tomb, amongst which are a blade, 'horns', and part of the hilt of a Minoan-type sword, lying on top of a bronze short sword with a similar gold handle Whilst this map concentrates principally on neighbouring Arzawa to show a rough estimation of its borders at the kingdom's height, it also clearly shows the approximate location of Ahhiyawa which, if anything, is even more mysterious than the little-recorded Arzawa (click or tap on map to view full sized)

Whilst this map concentrates principally on neighbouring Arzawa to show a rough estimation of its borders at the kingdom's height, it also clearly shows the approximate location of Ahhiyawa which, if anything, is even more mysterious than the little-recorded Arzawa (click or tap on map to view full sized) The team work on the track which leads to the tomb of the unknown, but very wealthy and well-honoured Mycenaean near the city of Orchomenus in Boeotia in this discovery of one of the richest graves of its type

The team work on the track which leads to the tomb of the unknown, but very wealthy and well-honoured Mycenaean near the city of Orchomenus in Boeotia in this discovery of one of the richest graves of its type This illustration is another artist's impression of an unspecified version of Troy, although it is believed to be based on the city which existed around the time of the Trojan War, shortly before its defeat and destruction

This illustration is another artist's impression of an unspecified version of Troy, although it is believed to be based on the city which existed around the time of the Trojan War, shortly before its defeat and destruction Climate-induced drought in the thirteenth century BC created great instability in the entire eastern Mediterranean region, resulting in mass migration in the Balkans, as well as the fall of city states and kingdoms further east (click or tap on map to view full sized)

Climate-induced drought in the thirteenth century BC created great instability in the entire eastern Mediterranean region, resulting in mass migration in the Balkans, as well as the fall of city states and kingdoms further east (click or tap on map to view full sized) Mycenae was already in ruins by the start of the first millennium AD, having been abandoned during the fall of Mycenaean Greece

Mycenae was already in ruins by the start of the first millennium AD, having been abandoned during the fall of Mycenaean Greece This actual footage of the ruins of Pavlopetri on the sea bed has been enhanced with computer-generated images to show the original building in context with the present site

This actual footage of the ruins of Pavlopetri on the sea bed has been enhanced with computer-generated images to show the original building in context with the present site