Stoicism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (original) (raw)

Stoicism originated as a Hellenistic philosophy, founded in Athens by Zeno of Citium (modern day Cyprus), c. 300 B.C.E. It was influenced by Socrates and the Cynics, and it engaged in vigorous debates with the Skeptics, the Academics, and the Epicureans. The name comes from the Stoa Poikile, or painted porch, an open market in Athens where the original Stoics used to meet and teach philosophy. Stoicism moved to Rome where it flourished during the period of the Empire, alternatively being persecuted by Emperors who disliked it (for example, Vespasian and Domitian) and openly embraced by Emperors who attempted to live by it (most prominently Marcus Aurelius). It influenced Christianity, as well as a number of major philosophical figures throughout the ages (for example, Thomas More, Descartes, Spinoza), and in the early 21st century saw a revival as a practical philosophy associated with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and similar approaches. Stoicism is a type of eudaimonic virtue ethics, asserting that the practice of virtue is both necessary and sufficient to achieve happiness (in the eudaimonic sense). However, the Stoics also recognized the existence of “indifferents” (to eudaimonia) that could nevertheless be preferred (for example, health, wealth, education) or dispreferred (for example, sickness, poverty, ignorance), because they had (respectively, positive or negative) planning value with respect to the ability to practice virtue. Stoicism was very much a philosophy meant to be applied to everyday living, focused on ethics (understood as the study of how to live one’s life), which was in turn informed by what the Stoics called “physics” (nowadays, a combination of natural science and metaphysics) and what they called “logic” (a combination of modern logic, epistemology, philosophy of language, and cognitive science).

Stoicism originated as a Hellenistic philosophy, founded in Athens by Zeno of Citium (modern day Cyprus), c. 300 B.C.E. It was influenced by Socrates and the Cynics, and it engaged in vigorous debates with the Skeptics, the Academics, and the Epicureans. The name comes from the Stoa Poikile, or painted porch, an open market in Athens where the original Stoics used to meet and teach philosophy. Stoicism moved to Rome where it flourished during the period of the Empire, alternatively being persecuted by Emperors who disliked it (for example, Vespasian and Domitian) and openly embraced by Emperors who attempted to live by it (most prominently Marcus Aurelius). It influenced Christianity, as well as a number of major philosophical figures throughout the ages (for example, Thomas More, Descartes, Spinoza), and in the early 21st century saw a revival as a practical philosophy associated with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and similar approaches. Stoicism is a type of eudaimonic virtue ethics, asserting that the practice of virtue is both necessary and sufficient to achieve happiness (in the eudaimonic sense). However, the Stoics also recognized the existence of “indifferents” (to eudaimonia) that could nevertheless be preferred (for example, health, wealth, education) or dispreferred (for example, sickness, poverty, ignorance), because they had (respectively, positive or negative) planning value with respect to the ability to practice virtue. Stoicism was very much a philosophy meant to be applied to everyday living, focused on ethics (understood as the study of how to live one’s life), which was in turn informed by what the Stoics called “physics” (nowadays, a combination of natural science and metaphysics) and what they called “logic” (a combination of modern logic, epistemology, philosophy of language, and cognitive science).

Table of Contents

- Historical Background

- The First Two Topoi

- The Third Topos: Ethics

- Apatheia and the Stoic Treatment of Emotions

- Stoicism after the Hellenistic Era

- Contemporary Stoicism

- Glossary

- References and Further Readings

1. Historical Background

Classically, scholars recognize three major phases of ancient Stoicism (Sedley 2003): the early Stoa, from Zeno of Citium (the founder of the school, c. 300 B.C.E.) to the third head of the school, Chrysippus; the middle Stoa, including Panaetius and Posidonius (late II and I century B.C.E.); and the Roman Imperial period, or late Stoa, with Seneca, Musonius Rufus, Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius (I through II century C.E.). Of course, Stoicism itself originated as a modification from previous schools of thought (Schofield 2003), and its influence extended well beyond the formal closing of the ancient philosophical schools by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I in 529 C.E. (Verbeke 1983; Colish 1985; Osler 1991).

a. Philosophical Antecedents

Stoicism is a Hellenistic eudaimonic philosophy, which means that we can expect it to be influenced by its immediate predecessors and contemporaries, as well as to be in open critical dialogue with them. These includes Socratic thinking, as it has arrived to us mainly through the early Platonic dialogues; the Platonism of the Academic school, particularly in its Skeptical phase; Aristotelianism of the Peripatetic school; Cynicism; Skepticism; and Epicureanism. It is worth noting, in order to put things into context, that a quantitative study of extant records concerning known philosophers of the ancient Greco-Roman world (Goulet 2013) estimates that the leading schools of the time were, in descending order: Academics-Platonists (19%), Stoics (12%), Epicureans (8%), and Peripatetics-Aristotelians (6%).

Eudaimonia was the term that meant a life worth living, often translated nowadays as “happiness” in the broad sense, or more appropriately, flourishing. For the Greco-Romans this often involved—but was not necessarily entirely defined by—excellence at moral virtues. The idea is therefore closely related to that of virtue ethics, an approach most famously associated with Aristotle and his Nicomachean Ethics (Broadie & Rowe 2002), and revived in modern times by a number of philosophers, including Philippa Foot (2001) and Alasdair MacIntyre (1981/2013).

Stoicism is best understood in the context of the differences among some of the similar schools of the time. Socrates had argued—in the Euthydemus, for instance (McBrayer et al. 2010)—that virtue, and in particular the four cardinal virtues of wisdom, courage, justice and temperance, are the only good. Everything else is neither good nor bad in and of itself. By contrast, for Aristotle the virtues (of which he listed a whopping twelve) were necessary but not sufficient for eudaimonia. One also needed a certain degree of positive goods, such as health, wealth, education, and even a bit of good looks. In other words, Aristotle expounded the rather commonsensical notion that a flourishing life is part effort, because one can and ought to cultivate one’s character, and part luck, in the form of the physical and cultural conditions that affect and shape one’s life.

Contrast this to the rather extreme (even for the time) take of the Cynics, who not only thought that virtue was the only good, like Socrates, but that the additional goods that Aristotle was worried about were actually distractions and needed to be positively avoided. Cynics like Diogenes of Sinope were famous for their ascetic and shall we say rather eclectic life style, as is epitomized by a story about him told by Diogenes Laertius (VI.37): “One day, observing a child drinking out of his hands, he cast away the cup from his wallet with the words, ‘A child has beaten me in plainness of living.’”

Diogenes and the boy without the cup

One way to think of this is that the Aristotelian approach comes across as a bit too aristocratic: if one does not have certain privileges in life, one cannot achieve eudaimonia. By contrast, the Cynics were preaching a rather extreme minimalist lifestyle, which is hard to practice for most human beings. What the Stoics tried to do, then, was to strike a balance in the middle, by endorsing the twin crucial ideas, on which I will elaborate later, that virtue is the only true good, in itself sufficient for eudaimonia regardless of one’s circumstances, but also that other things—like health, education, wealth—may be rationally preferred (Proēgmena) or “dispreferred” (Apoproēgmena), as in the case of sickness, ignorance, and poverty, as long as one did not confuse them for things with inherent value.

b. Greek Stoicism

The “Greek” phase of the Stoa covers the first and second periods, from the founding of the school by Zeno to the shifting of the center of gravity from Athens to Rome in the time of Posidonius in the I Century B.C.E., who became a friend of Cicero—not a Stoic himself, but one of our best indirect sources on early Stoicism. Stoicism was not just born, but flourished in Athens, even though most of its exponents originated from the Eastern Mediterranean: Zeno from Citium (modern Cyprus), Cleanthes from Assos (modern Western Turkey), and Chrysippus from Soli (modern Southern Turkey), among others. According to Medley (2003), this pattern is simply a reflection of the dominant cultural dynamics of the time, affected as they were by the conquests of Alexander.

From the beginning Stoicism was squarely a “Socratic” philosophy, and the Stoics themselves did not mind such a label. Zeno began his studies under the Cynic Crates, and Cynicism always had a strong influence on Stoicism, all the way to the later writings of Epictetus. But Zeno also counted among his teachers Polemo, the head of the Academy, and Stilpo, of the Megarian school founded by Euclid of Megaria, a pupil of Socrates. This is relevant because Zeno came to elaborate a philosophy that was both of clear Socratic inspiration (virtue is the Chief Good) and a compromise between Polemo’s and Stilpo’s positions, as the first one endorsed the idea that there are external goods—though they are of secondary importance—while the second one claimed that nothing external can be good or bad. That compromise consisted in the uniquely Stoic notion that external goods are of ethically neutral value, but are nonetheless the object of natural pursuit.

Zeno established the tripartite study of Stoic philosophy (see the three topoi[[hyperlink]]) comprising ethics, physics and logic. The ethics was basically a moderate version of Cynicism; the physics was influenced by Plato’s Timaeus (Taran 1971) and encompassed a universe permeated by an active (that is, rational) and a passive principle, as well as a cosmic web of cause and effect; the logic included both what we today refer to as formal logic and epistemology, that is, a theory of knowledge, which for the Stoics was decidedly empiricist-naturalistic.

The Stoics after Zeno disagreed on a number of issues, often interpreting Zeno’s teachings differently. Perhaps the most important example is provided by the dispute between Cleanthes and Chrysippus about the unity of the virtues: Zeno had talked about each virtue in turn being a kind of wisdom, which Cleanthes interpreted in a strict unitary sense (that is, all virtues are one: wisdom), while Chrysippus understood in a more pluralistic fashion (that is, each virtue is a “branch” of wisdom).

The early Stoics could also be stubbornly anti-empirical in their apologetics of Zeno’s writings, as when Chrysippus insisted in defending the idea that the heart, not the brain, is the seat of intelligence. This went against pretty conclusive anatomical evidence that was already available in the Hellenistic period, and earned the Stoics the scorn of Galen (for example, Tieleman 2002), though later Stoics did update their beliefs on the matter.

Despite this faux pas, Chrysippus was arguably the most influential Stoic thinker, responsible for an overhaul of the school, which had declined under the guidance of Cleanthes, a broad systematization of its teachings, and the introduction of a number of novel notions in logic—the aspect of Stoicism that has had the most technical philosophical impact in the long run. Famously, Diogenes Laertius (2015, VII.183) wrote that “But for Chrysippus, there had been no Porch.”

In the six decades following Chrysippus there were just two heads of the Stoa, Zeno of Tarsus (south-central Turkey) and Diogenes of Babylon, whose contributions were rather less significant than those of Chrysippus himself. We have to wait until 155 B.C.E. for the next impactful event, when the heads of the three major schools in Athens—the Stoics, the Academics and the Peripatetics—were sent by the city to Rome in order to help with diplomatic efforts. (It is interesting to note, as does Sedley (2003) that the fourth large school, the Epicurean one, was missing, following their stance of political non-involvement.) The philosophers in question, including the Stoic Diogenes of Babylon, made a huge impression on the Roman public with their public performances (and, apparently, an equally worrisome one on the Roman elite, thus beginning a long tradition of tension between philosophers and high-level politicians that characterized especially the post-Republican empire), paving the road for the later shift of philosophy from Athens to Rome, as well as other centers of learning, like Alexandria.

Beginning with Antipater of Tarsus, and then more obviously Panaetius (late II Century B.C.E.) and Posidonius (early I Century B.C.E.), the Stoics revisited their relationship with the Academy, especially in light of the above mentioned importance of the Timaeus for Stoic cosmology. Apparently, what particularly interested Posidonius was the fact that Plato’s main character in the dialogue is a Pythagorean, a school that Posidonius somewhat anachronistically managed to link to Stoicism.

It appears that the broader project pursued by both Panaetius and Posidonius was one of seeking common ground (Sedley 2003 uses the term “syncretism”) among Academicism, Aristotelianism and Stoicism itself, that is, the three branches of Socratic philosophy. This process seems to have been in part responsible for the further success of Stoicism once the major philosophers of the various schools moved from Athens to Rome, after the diaspora of 88-86 B.C.E.

c. Roman Stoicism

If the visit to Rome by the head of various philosophical schools in 155 B.C.E. was crucial for bringing philosophy to the attention of the Romans, the political events of 88-86 B.C.E. changed the course of Western philosophy in general, and Stoicism in particular, for the remainder of antiquity.

At that time philosophers, particularly the Peripatetic Athenion and—surprisingly—the Epicurean Aristion, were politically in charge at Athens, and made the crucial mistake of siding with Mithridates against Rome (Bugh 1992). The defeat of the King of Pontus, and consequently of Athens, spelled disaster for the latter and led to a diaspora of philosophers throughout the Mediterranean.

To be fair, we have no evidence of the continuation of the Stoa as an actual school in Athens after Panaetius (who often absented himself to Rome anyway), and we know that Posidonius taught in Rhodes, not Athens. However, according to Sedley (2003), it was the events of 88-86 B.C.E. that finally and permanently moved the center of gravity of Stoicism away from its Greek cradle to Rome, Rhodes (where an Epicurean school also flourished), and Tarsus, where a Stoic was at one point chosen by Augustus to govern the city.

Most crucially, however, Stoicism became important in Rome during the fraught time of the transition between the late Republic and the Empire, with Cato the Younger eventually becoming a role model for later Stoics because of his political opposition to the “tyrant” Julius Caesar. Sedley highlights two Stoic philosophers of the late First Century B.C.E., Athenodorus of Tarsus and Arius Didymus, as precursors of one of the greatest and most controversial Stoic figures, Seneca. Both Athenodorus and Arius were personal counselors to the first emperor, Augustus, and Arius even wrote a letter of consolation to Livia, Augustus’ wife, addressing the death of her son, which Seneca later hailed as a reference work of emotional therapy, the sort of work he himself engaged in and became famous for.

Once we get to the Imperial period (Gill 2003), we see a decided shift away from the more theoretical aspects of Stoicism (the “physics” and “logic,” see below) and toward more practical treatments of the ethics. However, as Gill points out, this should not lead us to think that the vitality of Stoicism had taken a nose dive by then: we know of a number of new treatises produced by Stoic writers of that period, on everything ranging from ethics (Hierocles’ Elements of Ethics) to physics (Seneca’s Natural Questions), and the Summary of the Traditions of Greek Theology by Cornutus is one of a handful of complete Stoic treatises to survive from any period of the history of the school. Still, it is certainly the case that the best known Stoics of the time were either teachers like Musonius Rufus and Epictetus, or politically active, like Seneca and Marcus Aurelius, thus shaping our understanding of the period as a contrast to the foundational and more theoretical one of Zeno and Chrysippus.

Importantly, it is from the late Republic and Empire that we also get some of the best indirect sources on Stoicism, particularly several books by Cicero (2014; for example., Paradox Stoicorum, De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum, Tusculanae Quaestiones, De Fato, Cato Maior de Senectute, Laelius de Amicitia, and De Officiis) and Diogenes Laertius’ Lives of the Eminent Philosophers (Book VII, 2015). And this literature went on to influence later writers well after the decline of Stoicism, particularly Plotinus (205-270 C.E.) and even the 6th Century C.E. Neoplatonist Simplicius.

All of the above notwithstanding, what is most vital about Stoicism during the Roman Imperial period, however, is also what arguably made the philosophy’s impact reverberate throughout the centuries, eventually leading to two revivals, the so-called Neostoicism of the Renaissance, and the current “modern Stoicism” movement to which I will turn at the end of this essay. The sources of such vitality were fundamentally two: on the one hand charismatic teachers like Musonius and Epictetus, and on the other hand influential political figures like Seneca and Marcus. Indeed, Musonius was, in a sense, both: not only he was a member of the Roman “knight” class, and the teacher of Epictetus, he was also politically active, openly criticizing the policies of both Nero and Vespasian, and getting exiled twice as a result. Others were not so lucky: Stoic philosophers suffered a series of persecutions from displeased emperors, which resulted in murders or exile for a number of them, especially during the reigns of Nero, Vespasian and Domitian. Seneca famously had to commit suicide on Nero’s orders, and Epictetus was exiled to Greece (where he established his school at Nicopolis) by Domitian.

It is also important to appreciate different “styles” of being Stoic among the major Roman figures. As Gill (2003) points out, Epictetus was rather strict, arching back to the Cynic model of quasi-asceticism (see, for instance, his “On Cynicism” in Discourses III.22). Musonius was a sometimes odd combination of “conservative” and “progressive” Stoic, advocating the importance of marriage and family, but also stating very clearly that women are just as capable of practicing virtue and philosophizing as men are, and moreover that it is hypocritical of men to consider their extramarital sexual activities differently from those of women! Seneca was not only more open to the pursuit of “preferred indifferents” (he was a wealthy Senator, but it seems unfair to accuse him of endorsing a simplistic self-serving philosophy: see the nuanced biographies by Romm 2014 and Wilson 2014), but explicitly stated that he was critical of some of the doctrines of the early Stoics, and that he was open to learn from other schools, including the Epicureans. Famously, Marcus Aurelius was open—one would almost want to say agnostic—about theology, at several points in the Meditations (1997) explicitly stating the two alternatives of “Providence” (Stoic doctrine) or “Atoms” (the Epicurean take), for instance: “Either there is a fatal necessity and invincible order, or a kind Providence, or a confusion without a purpose and without a director. If then there is an invincible necessity, why do you resist? But if there is a Providence that allows itself to be propitiated, make yourself worthy of the help of the divinity. But if there is a confusion without a governor, be content that in such a tempest you have yourself a certain ruling intelligence” (XII.14); or: “With respect to what may happen to you from without, consider that it happens either by chance or according to Providence, and you must neither blame chance nor accuse Providence” (XII.24). More is said about this specific topic in the section on Stoic metaphysics and teleology.

There is ample evidence, then, that Stoicism was alive and well during the Roman period, although the emphasis did shift—somewhat naturally, one might add—from laying down the fundamental ideas to refining them and putting them into practice, both in personal and social life.

d. Debates with Other Hellenistic Schools

One should understand the evolution of all Hellenistic schools of philosophy as being the result of continuous dialogue amongst themselves, a dialogue that often led to partial revisions of positions within any given school, or to the adoption of a modified notion borrowed from another school (Gill 2003). To have an idea of how this played out for Stoicism, let us briefly consider a few examples, related to the interactions between Stoicism and Epicureanism, Aristotelianism, and Platonism—without forgetting the direct influence that Cynicism had on the very birth of Stoicism and all the way to Epictetus.

Epictetus is pretty explicit about his—negative—opinions of the Epicureans, drawing as sharp a contrast as possible between the latter’s concern with pleasure and pain and the Stoic focus on virtue and integrity of character. For example, Discourses I.23 is entitled “Against Epicurus,” and begins: “[1] Even Epicurus realizes that we are social creatures by nature, but once he has identified our good with the shell, he cannot say anything inconsistent with that. [2] For he further insists—rightly—that we must not respect or approve anything that does not share in the nature of what is good.” “The shell” here is the body, a reference to the Epicureans’ insistence on pleasure and the absence of pain as what leads to ataraxia, or tranquillity of mind—a term interestingly different from the one preferred by the Stoics, apatheia, or lack of disturbing emotions, as shall be seen below.

A longer section, II.20, is entitled “Against the Epicureans and the Academics,” at the beginning of which Epictetus calls the bluff, in his mind, on the rivals’ theories, which he understands as clearly impractical and contrary to common sense: “[1] Even people who deny that statements can be valid or impressions clear [that is, the Skeptics] are obliged to make use of both. You might almost say that nothing proves the validity of a statement more than finding someone forced to use it while at the same time denying that it is sound.” Epictetus even goes so far as suggesting that Epicurus is incoherent, as he advises a life of retired tranquility away from society, and yet bothers to write books about it, thus showing himself to be concern about the welfare of society after all: “[15] What urged him to get out of bed and write the things he wrote was, of course, the strongest element in a human being—nature—which subjected him to her will despite his loud resistance.”

Attacking the Skeptics among the Academics, Epictetus turns up the rhetoric significantly: “What a travesty! [28] What are you doing? You prove yourself wrong on a daily basis and still you won’t give up these idle efforts. When you eat, where do you bring your hand—to your mouth, or to your eye? What do you step into when you bathe? When did you ever mistake your saucepan for a dish, or your serving spoon for a skewer?” And he sees his invective as justified—in sure Stoic fashion—not on theoretical grounds, but on practical ones: “[35] We could give adulterers grounds for rationalizing their behavior; such arguments could provide pretexts to misappropriate state funds; a rebellious young man could be emboldened further to rebel against his parents. So what, according to you, is good or bad, virtuous or vicious—this or that?”

Even so, not all Stoics rejected either Academic or Epicurean ideas altogether. I have mentioned Marcus Aurelius’ relative “agnosticism” about Providence vs. Atoms (though he clearly preferred the first option, in line with standard Stoic teaching), and Seneca is often sympathetic to Epicurean views, though, as Gill (2003, note 58) comments, this is in the spirit of showing that even some of the rival school’s ideas are congruent with Stoic ones. He very clearly states, however, in Natural Questions: “I do not agree with [all] the views of our school” (2014, VII.22.1).

Cicero, in Book III of De Finibus, provides us with some glimpses of the disagreement between Stoics and Aristotelians, by way of his imaginary dialogue with Cato the Younger. At [41] he writes: “Carneades never ceased to contend that on the whole so-called ‘problem of good and evil,’ there was no disagreement as to facts between the Stoics and the Peripatetics, but only as to terms. For my part, however, nothing seems to me more manifest than that there is more of a real than a verbal difference of opinion between those philosophers on these points.” He continues: “The Peripatetics say that all the things which under their system are called goods contribute to happiness; whereas our school does not believe that total happiness comprises everything that deserves to have a certain amount of value attached to it,” referring to the different treatment of “external goods” between Aristotelians and Stoics.

There are well documented examples of Stoic opinions changing in direct response to challenges from other schools, for instance the modified position on determinism that was adopted by Philopator (80-140 C.E.), a result of criticism from both the Peripatetic and the Middle Platonist philosophers. We also have clear instances of Stoic ideas being incorporated by other schools, as in the case of Antiochus of Ascalon (130-69 B.C.E.), who introduced Stoic notions in his revision of Platonism, justifying the move by claiming that Zeno (and Aristotle, for that matter) developed ideas that were implicit in Plato (Gill 2003). Finally, Stoicism found its way into Christianity via Middle Platonism, at the least since Clement of Alexandria (150-215 C.E.).

2. The First Two Topoi

A fundamental aspect of Stoic philosophy is the twofold idea that ethics is central to the effort, and that the study of ethics is to be supported by two other fields of inquiry, what the Stoics called “logic” and “physics.” Together, these form the three topoi of Stoicism.

We will take a closer look to each topos in turn, but it is first important to see why and how they are connected. Stoicism was a practical philosophy, the chief goal of which was to help people live a eudaimonic life, which the Stoics identified with a life spent practicing the cardinal virtues (next section). Later in the Roman period the emphasis shifted somewhat to the achievement of apatheia, but this too was possible because of the practice of the topos of ethics.

This, in turn, was to be supported by the study of the other two topoi, “logic,” which was more expansive than the modern technical meaning of the term, including logic sensu stricto, but also a theory of knowledge (that is, epistemology), as well as cognitive science, and “physics,” by which the Stoics meant roughly what we would today identify as a combination of natural science and metaphysics (the latter including theology). Roughly, then, “logic” means the study of how to reason about the world, while “physics” means the study of that world.

Logic and Physics are related to Ethics because Stoicism is a thoroughly naturalistic philosophy. Even when the Stoics are talking about “God” or “soul,” they are referring to physical entities, respectively identified with the rational principle embedded in the universe itself and with whatever makes human rationality possible. Stoics often invoked creative imagery to explain the relationship among Physics, Logic and Ethics, as found in Diogenes Laertius (VII.39), for instance. Perhaps the most famous of such analogies is the one using an egg, where the shell is the Logic, the white the Ethics, and red part the Physics. However, given how the three topoi were meant to relate to each other, this is probably misleading, possibly due to a misunderstanding of the biology of eggs (the Physics is supposed to be nurturing the Ethics, which means that the former should be the white and the latter the red part of the egg). The best simile in my mind is that of a garden: the fence is the Logic—defending the precious inside and defining its boundaries; the fertile soil is the Physics—providing the nutritive power by way of knowledge of the world; and the resulting fruits are the Ethics—the actual focal objective of Stoic teachings.

While the Stoics disagreed on the sequence in which the three topoi should be presented to students (that is, just like faculty in a modern university, they had contrasting opinions about the merits of different curricula!), the crucial point is that of a naturalistic philosophy where there is no sharp distinction between “is” and “ought,” as assumed in much modern moral philosophy, because what an agent ought to do (Ethics) is in fact closely informed by that agent’s knowledge of the workings of the world (Physics) as well as her capacity to reason correctly (Logic). This section describes the first two topoi and the next describe Ethics.

a. “Logic”

Stoics made important early contributions to both epistemology (Hankinson 2003) and logic proper (Bobzien 2003), and much has, deservedly, been written about it. While Stoics held that the Sage, who was something of an ideal figure, could achieve perfect knowledge of things, in practice they relied on a concept of cognitive progress, as well as moral progress, since both logic and physics are related to, and indeed function in the service of, ethics. They referred to this idea as prokopê (making progress), and they engaged in a long running dispute with Academic Skeptics about just how defensible this notion actually is.

Unlike the Epicureans, Stoics did not maintain that all impressions are true, but rather that some of them were “cataleptic” (that is, leading to comprehension) and others were not. Diogenes Laertius explains the difference (VII.46): “the cataleptic, which [the Stoics] hold to be the criterion of matters, is that which comes from something existent and is in accordance with the existent thing itself, and has been stamped and imprinted; the non-cataleptic either comes from something non-existent, or if from something existent then not in accordance with the existent thing; and it is neither clear, nor distinct.”

So the Stoics did admit that one’s perception can be wrong, as in cases of hallucinations, or dreams, or other sources of phantasma (that is, impressions on the mind, the result of automatic—we would say unconscious—judgment), but also that proper training allows one to make progress in distinguishing cataleptic from non-cataleptic impressions (that is, impressions to which we may reasonably give or withhold assent). Chrysippus even suggested that it is important to absorb a number of impressions, since it is the accumulation of impressions that leads to concept-formation and to making progress. In this sense, the Stoic account of knowledge was eminently empiricist in nature, and—especially after relentless Skeptical critiques—relied on something akin to what moderns call inference to the best explanation (Lipton 2003), as in their conclusion that our skin must have holes based on the observation that we sweat.

It is important to realize that a cataleptic impression is not quite knowledge. The Stoics distinguished among opinion (weak, or false), apprehension (characterized by an intermediate epistemic value), and knowledge (which is based on firm impressions unalterable by reason). Giving assent to a cataleptic impression is a step on the way to actual knowledge, but the latter is more structured and stable than any single impression could be. In a sense, then, the Stoics held to a coherentist view of justification (for example, Angere 2007), and ultimately, like all ancients, to a correspondence theory of truth (for example, O’Connor 1975).

Hankinson (2003) comments on an interesting aspect of the dispute between Stoics and Academic Skeptics, concerning the epistemic warrant to be granted to cataleptic impressions. What, precisely, makes them “clear and distinct,” a Stoic terminology that clearly anticipates Descartes (who, obviously, was not an empiricist)? If clarity and distinctiveness are internal features of cataleptic impressions, then these are phenomenal features, and it is easy to come up with counterexamples where they do not seem to work (for instance, the common occurrence of mistaking one member of a pair of twins for the other one).

This is where we encounter one of the many episodes of growth of Stoic thought in response to external pressure. Cicero tells us (2014, in Academica II.77) that Zeno was aware that the same impression could derive from something that did or did not exist, so he modified his stance (as Diogenes Laertius reports: VII.50), adding the following clause: “of such a type as could not come from something non-existent.” Of course this does not solve the issue, but it builds on the Stoic metaphysical assumption that there cannot be two things that are exactly alike, as much as at times it may appear so to us. Frede (1983) advanced the further view that what makes a cataleptic impression clear and distinct is not any internal feature of that impression, but rather an external causal feature related to its origin. According to this account, then, Stoic epistemology is externalist (for example, Almeder 1995), rather than internalist (for example, Goldman 1980). Indeed, there is evidence that they became—again as a result of criticism from the Skeptics—reliabilists about knowledge (Goldman 1994). Athenaeus tells of the story of Sphaerus, a student of Cleanthes and colleague of Chrysippus, who was shown at a banquet what turned out to be birds made of wax. After he reached to pick one up he was accused of having given assent to a false impression. To which he—rather cleverly, but indicatively—replied that he had merely assented to the proposition that it was reasonable to think of the objects as actual birds, not to the stronger claim that they actually were birds.

When it comes to the area of Stoic “logic” that is closest to our, much narrower, conception of the field, the school made major contributions. Their system of syllogistics recognized that not all valid arguments are syllogisms and significantly differs from Aristotle’s, having more in common with modern-day relevance logic (Bobzien 2006). To simplify quite a bit (but see Bobzien 2003 for a somewhat in-depth treatment), Stoic syllogistics was built on five basic types of syllogisms, and complemented by four rules for arguments that could be deployed to reduce all other types of syllogisms to one of the basic five.

The broader Stoic approach to logic has been characterized as a type of propositional logic, anticipating aspects of Frege’s work (Beaney 1997). Stoic logic made a fundamental distinction between “sayables” and “assertibles.” The former are a broader category that includes assertibles as well as questions, imperatives, oaths, invocations and even curses. The assertibles then are self-complete sayables that we use to make statements. For instance, “If Zeno is in Athens then Zeno is in Greece” is a conditional composite assertible, constructed out of the individual simple assertibles “Zeno is in Athens” and “Zeno is in Greece.” A major difference between Stoic assertibles and Fregean propositions is that the truth or falsehood of assertibles can change with time: “Zeno is in Athens” may be true now but not tomorrow, and it may become true again next month. It is also important to note that truth or falsehood are properties of assertibles, and indeed that being either true or false is a necessary and sufficient condition for being an assertible (that is, one cannot assert, or make statements about, things that are neither true nor false).

The Stoics were concerned with the validity of arguments, not with logical theorems or truths per se, which again is understandable in light of their interest to use logic to guard the fruits of their garden, the ethics. They also introduced modality into their logic, most importantly the modal properties of necessity, possibility, non-possibility, impossibility, plausibility and probability. This was a very modern and practically useful approach, as it directed attention to the fact that some assertibles induce assent even though they may be false, as well as to the observation that some assertibles have a higher likelihood of being true than not. Finally, the Stoics, and Chrysippus in particular, were sensitive to and attempted to provide an account of logical paradoxes such as the Liar and Sorites cases along lines that we today recognize as related to a semantic of vagueness (Tye 1994).

b. “Physics”

The Stoic topos of Physics includes what we today would classify as natural science (White 2003), metaphysics (Brunschwig 2003), and theology (Algra 2003). Let us briefly look at each in turn.

When it comes to natural science and cosmology, recall that the Stoics sought to “live according to nature,” which requires us to make our best efforts to understand nature. This also implies a very different view of natural science from the modern one: its study is not an end in itself, but rather subordinate to help us live a eudaimonic life.

Stoics thought that everything real, that is, everything that exists, is corporeal—including God and soul. They also recognized a category of incorporeals, which included things like the void, time, and the “sayables” (meanings, which played an important role in Stoic Logic). This may appear as a contradiction, given the staunchly materialist nature of Stoics philosophy, but is really no different from a modern philosophical naturalist who nonetheless grants that one can meaningfully talk about abstract concepts (“university,” “the number four”) which are grounded in materialism because they can only be thought of by corporeal beings such as ourselves.

They embraced what we might call a “vitalist” understanding of nature, which is permeated by two principles: an active one (identified with reason and God, referred to as the Logos) and a passive one (substance, matter). The active principle is un-generated and indestructible, while the passive one—which is identified with the four classical elements of water, fire, earth and air—is destroyed and recreated at every, eternally recurring, cosmic conflagration, a staple of Stoic cosmology. The cosmos itself is a living being, and its rational principle (Logos) is identified with aether, or the Stoic Fire (not to be confused with the elemental fire that is part of the passive principle). Consequently, God is immanent in the universe, and it is in fact identified with the creative cosmic Fire. This also means that the Stoics, unlike the Aristotelians, did not recognize the concept of a prime mover, nor of a Christian-type God outside of time and space, on the ground that something incorporeal cannot act on things, because it has no causal powers. From all of this, as White (2003) puts it, emerges a biological, rather than a mechanical picture of causation, which is significantly different from post-Cartesian and Newtonian mechanical philosophy.

Cosmic conflagrations, for the Stoics, repeat themselves in exact manner, apparently because God/Nature laid out things in the best possible way the previous time around, and there is therefore no reason to change (though one would get the same outcome from an entirely deterministic causal model of the universe). It is interesting to muse about the fact that some modern cosmological models also predict either identical or varied recurring universes (Ungerer and Smolin 2014), but of course do away with the concept of Providence altogether. According to Eusebius (quoted by White), during the phase of cosmic conflagration, the creative Fire is “a sort of seed, which possesses the principles of all things and the causes of all things that have occurred, are occurring, and will occur—the interweaving and ordering of which is fate, knowledge, truth, and a certain inevitable and inescapable law of the things that exist.”

Cicero, in De Fato, lays out the Stoic theory of causality and actually equates fate with antecedent causes. Chrysippus had argued that there is no possibility of motion without causes, deducing that therefore everything has a cause. This concept of universal causality led the Stoics to accept divination as a branch of physics, not a superstition, as explained again by Cicero in De Divinatione, and this makes sense once one understands the Stoic view of the cosmos: predicting the future is not something that one does by going outside the laws of physics, but by intelligently exploiting such laws.

Metaphysically the Stoics were determinists (Frede 2003). Here is Cicero: “[the Stoics] say, that it is impossible, when all the circumstances surrounding both the cause and that of which it is a cause are the same, that things should not turn out a certain way on one occasion but that they should turn out that way on some other occasion” (De Fato, 199.22-25). The Stoics did have a concept of chance, but they thought of it (much like modern scientists) as a measure of human ignorance: random events are simply events whose causes are not understood by humans.

The consequences of Stoic physics for their ethics are clear, and are summarized again by Cicero, when he says that Chrysippus aimed at a middle position between what we today would call strict incompatibilism and libertarianism (Griffith 2013). White (2003) interestingly notes in this respect that—just like Spinoza—the Stoics shifted the emphasis from moral responsibility to moral worth and dignity.

In terms of fundamental ontology, the Stoics were anti-corpuscularian (unlike the pre-Socratic Atomists, and Stoics’ chief rivals, the Epicureans), on the grounds that the idea of atoms violated their concept of a seamless unity of the cosmos. It is tempting to see this as in the same ballpark of modern quantum mechanical theories that see the entire universe as constituted of a single “wave function” (Ladyman and Ross 2009), but of course this would be an anachronistic interpretation.

3. The Third Topos: Ethics

Stoic Ethics was not just another theoretical subject, but an eminently practical one. Indeed, especially for the later Stoics, ethics—understood as the study of how to live one’s life—was the point of doing philosophy. It was no easy task: Epictetus famously said (in Discourses III.24.30): “The philosopher’s lecture room is a hospital: you ought not to walk out of it in a state of pleasure, but in pain—for you are not in good condition when you arrive!” The starting point for Epictetus was the famous dichotomy of control, as expressed at the very beginning of the Enchiridion: “We are responsible for some things, while there are others for which we cannot be held responsible” (also translated as “Some things are up to us, other things are not up to us”).

The early Stoics were somewhat more theoretical in their approach, with Zeno, Cleanthes and Chrysippus attempting to both systematize their doctrines and defend them from critiques from both Epicurean and especially Academic-Skeptic quarters. The early Stoa’s famous motto in ethics was “follow nature” (or “live according to nature”), by which they meant both the rational-providential aspect of the cosmos (see Physics above) and more specifically human nature, which they conceived as that of a social animal capable of bringing rational judgment to bear on problems posed by how to live one’s life. (It appears that Zeno’s original articulation of the principle was “live consistently” to which Cleanthes added the clarifying clause “with nature”: Schofield 2003.) Tightly related to this idea of following (human) nature was the Stoic concept of oikeiôsis, often translated as affinity, or appropriation. For the Stoics human beings have natural propensities to develop morally, propensities that begin as what we today would call instincts and can then be greatly refined with the onset of the age of reason at the childhood stage and beyond. It is interesting to note that this naturalistic account of the roots of virtuous/moral behavior is highly compatible with modern findings in both evolutionary and cognitive science (for example, Putnam and others 2014).

Specifically, we naturally: (i) behave in a fashion as to advance our interests and goals (health, wealth, and so forth); (ii) identify with other people’s interests (initially our parents, then friends, then countrymen); (iii) figure out ways to practically navigate the vicissitudes of life. The Stoics related these propensities directly to the four cardinal virtues of temperance, courage, justice and practical wisdom. Temperance and courage are required to pursue our goals, justice is a natural extension of our concern for an ever-increasing circle of people, and practical wisdom (phronêsis) is what best allows us to deal with whatever happens.

Which brings us to the matter of how the virtues are related to each other. To begin with, the Stoics recognized the above mentioned four cardinal virtues, but also a number of more specific ones within each major category (complete list in Sharpe 2014, derived from Stobaeus): for instance, practical wisdom included good judgment, discretion, resourcefulness; temperance could be broken down into propriety, sense of honor, self-control; courage was divided into perseverance, confidence, magnanimity; and justice comprised piety, kindness, sociability. Even so, they held to a view of virtue that is much more unitary than it may come across from this kind of list (Schoefield 2003). The cardinal virtues are derived from Socrates, especially in Plato’s Republic, and so is a certain unifying way of considering the virtues. Justice can be conceptualized as practical wisdom applied to social living; courage as wisdom concerning endurance; and temperance as wisdom with regard to matters of choice. Chrysippus further elaborated this idea of pluralism within an underlying unity, making the virtues essentially inseparable, so that, say, one cannot be courageous and yet intemperate—in the Stoic sense of those words.

Hadot (1998) draws a series of parallels between the four virtues, the three topoi and what are referred to as the three Stoic disciplines: desire, action, and assent. The discipline of desire, sometimes referred to as Stoic acceptance, is derived from the study of physics, and in particular from the idea of universal cause and effect. It consists in training oneself to desire what the universe allows and not to pursue what it does not allow. A famous metaphor here, used by Epictetus, is that of a dog leashed to a cart: the dog can either fight the cart’s movement at every inch, thus hurting himself and ending up miserable; or he can decide to gingerly go along with the ride and enjoy the panorama. This is a version of what Nietzsche eventually called amor fati (love your fate), and that is encapsulated in Epictetus’ phrase “endure [what the universe throws your way] and renounce [what the universe does not allow]” (Fragments 10). Consequently, according to Hadot, the discipline of desire is linked to the virtues of courage (to follow the order of the cosmos) and temperance (to be able to control one’s desires).

The second discipline, of action, is also called Stoic “philanthropy” and is the most prosocial of the cardinal virtues. The basic idea is that human beings ought to develop their natural concern for others in a way that is congruent with the exercise of the virtue of justice. Here the area of study most directly connected to the discipline is that of ethics itself. A representative quote is perhaps the one found in Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations (VIII.59): “Men exist for the sake of one another. Teach them then or bear with them.” The first sentence is a statement of philanthropy (in the Stoic, not modern, sense), while the second one makes it clear that for the emperor this was a duty to be performed either by engaging other people positively or at the very least by suffering their non virtuous behavior, if that is the case.

The last discipline is that of assent, referred to as Stoic “mindfulness” (not to be confused with the variety of Buddhist concepts by the same name, especially the Zen one). I will get back to the concept of assent in the next section, as it is related to the Stoic treatment of the (moral) psychology of emotions, but for now suffice to say that the discipline regards the necessity to make decisions about what to accept or reject of our experience of the world, that is, how to make proper judgments. It is therefore linked to the virtue of practical wisdom, as well as to the area of study of logic. If we had to summarize it in a single sentence, Seneca’s “bring the mind to bear upon your problems” (On Tranquility of Mind, X.4) may be appropriate.

As we have seen so far, Stoic ethics is concerned exclusively with the concept of virtue (and associated disciplines)—whether understood as a unitary thing with a number of facets or otherwise. In this the Stoics were akin to the Cynics and unlike the Peripatetics, who instead allowed that a number of other things are necessary for a eudaimonic life, including (some) wealth, health, education, and so forth. The Peripatetics would not have assented to the idea of a eudaimonic Sage on the rack, a classic Stoic concept.

However, Stoic ethics actually attempts to strike a balance between the asceticism of the Cynics and the somewhat elitist views of the Peripatetics. It does so through the introduction of the Stoic concept of preferred and dispreferred “indifferents” briefly mentioned at the beginning. This is found already in Zeno’s book on Ethics, which is now lost, but about which we know from Diogenes Laertius (VII.4). Zeno distinguished between indifferents that have value (axia) and those that have disvalue (apaxia). The first group included things like health, wealth and education, while the second group was comprised of things like sickness, poverty and ignorance. The move was a brilliant one: as I argued above, it allowed the Stoics to get the best of both the Cynic and the Peripatetic worlds: yes, it is true that—if they don’t get in the way of practicing virtue—some indifferents are preferred; but they are called indifferents for a reason: they do not truly matter for the pursuit of the (moral) eudaimonic life. In other words, while it is undeniable that people naturally and rationally seek the preferred indifferents, it is also the case that one can be a person of moral integrity, achieving eudaimonia, regardless of one’s material circumstances.

There is much more to be said about Stoic ethics, of course, but before closing this introductory sketch let me comment on an issue that does not fail to come up, and which I have already briefly mentioned above: the connection between the undeniably teleological-providential views of the cosmos advanced by Stoic physics and the actual practice of Stoic ethics. The issue is this: given that the Stoic themselves insisted that the study of physics (and of logic) influences how we understand ethics, and given that they believed in the providential nature of the cosmos, does that mean that only people who accept the latter view can pursuit eudaimonia? The generally accepted answer is no.

Gregory Vlastos (referred to in Schofield 2003) convincingly argued that what he called the “theocratic” principle does affect one’s conception of the relation between virtue and the order of the cosmos, specifically because it tells us that being virtuous is in agreement with such order. Crucially, however, Vlastos maintains that this does not change the content of virtue, nor does it affect one’s conception of eudaimonia. This is so because although the “physics” (which, remember, is a combination of natural sciences and metaphysics, and hence theology) does inform the ethics, it does so in what modern philosophers would call an underdetermined fashion: while ethics is not independent of physics (or logic), in the Stoic system, it also cannot be read directly off it. Stoic ethics is naturalistic, and thus very modern in nature, but it—to put it in rather anachronistic terms—does not simplistically erase Hume’s is/ought divide.

Vlastos’ position finds plenty of textual support from a number of Stoic sources, perhaps no more obviously so than in Marcus, as already reported. There are, however, other passages in the classical Stoic literature that do not lend themselves to a clear cut position on the matter, such as this one from Epictetus: “What does it matter to me […] whether the universe is composed of atoms or uncompounded substances, or of fire and earth? Is it not sufficient to know the true nature of good and evil, and the proper bounds of our desires and aversions, and also of our impulses to act and not to act; and by making use of these as rules to order the affairs of our life, to bid those things that are beyond us farewell? It may very well be that these latter things are not to be comprehended by the human mind, and even if one assumes that they are perfectly comprehensible, well what profit comes from comprehending them? And ought we not to say that those men trouble in vain who assign all this as necessary to the philosopher’s system of thought? […] What Nature is, and how she administers the universe, and whether she really exists or not, these are questions about which there is no need to go on to bother ourselves” (Fragments 1). Please remember that for the Stoics “nature” was synonymous with “god.”

Indeed, it is because of this and other passages that Ferraiolo (2015), for instance, concludes that: “metaphysical doctrines about the nature and existence of God, and a rationally governed cosmos, are rather cleanly separable from Stoic practical counsel, and its conductivity to a well-lived, eudaimonistic life. Stoicism may have developed within a worldview infused with presuppositions of a divinely-ordered universe … but the efficacy of Stoic counsel is not dependent upon creation, design, or any form of intelligent cosmological guidance.”

On balance, it seems fair to say that the ancient Stoics did believe in a (physical) god that they equated with the rational principle organizing the cosmos, and which was distributed throughout the universe in a way that can be construed as pantheistic. While it is the case that they maintained that an understanding of the cosmos informs the understanding of ethics, construed as the study of how to live one’s life, it can also be reasonably argued that Stoic metaphysics underdetermined—on the Stoics’ own conception—their ethics, thus leaving room for a “God or Atoms” position that may have developed as a concession to the criticisms of the Epicureans, who were atomists.

4. Apatheia and the Stoic Treatment of Emotions

The naturalistic system of ethics developed by the Stoics bridges what would later be referred to as the is/ought gap by way of a sophisticated account of human developmental moral psychology (Brennan 2003). This section focuses on a related, major difference between Stoics and Epicureans, which begins with the respective use of two key terms indicating a desirable state of mind according to the two schools, and continuing with a broader discussion of the Stoic classification of emotions (or “passions”).

As we have seen, Epictetus explains in a number of places where the Stoa differs from the Garden (for example, “Against Epicurus,” Discourses I.23), while Seneca tells his friend Lucilius that he happily borrows from Epicurus when it makes sense, as it is his “custom to cross even into the other camp, not as a deserter but as a spy” (Letter II, A beneficial reading program, in the new translation by Graver and Long 2015).

Recall that the Stoics thought the pivotal thing in life is virtue and its cultivation, while the Epicureans thought that the point was to seek moderate pleasure and especially avoid pain. Nonetheless, both schools thought that a crucial component of eudaimonia (the flourishing life) was something very similar, to which the Stoics referred to as apatheia and the Epicureans as ataraxia. There are, however, some differences between the two concepts, especially in the way the two schools taught how one could achieve, or at the least approximate, the respective states of mind.

The IEP article on Epictetus defines the two terms in the following fashion:

apatheia: freedom from passion, a constituent of the eudaimôn life

ataraxia: imperturbability, literally “without trouble,” sometimes translated as “tranquillity”; a state of mind that is a constituent of the eudaimôn life

So, both apatheia and ataraxia are components of the eudaimonic life, and indeed, while the second term is usually associated with the Epicureans, both schools used it.

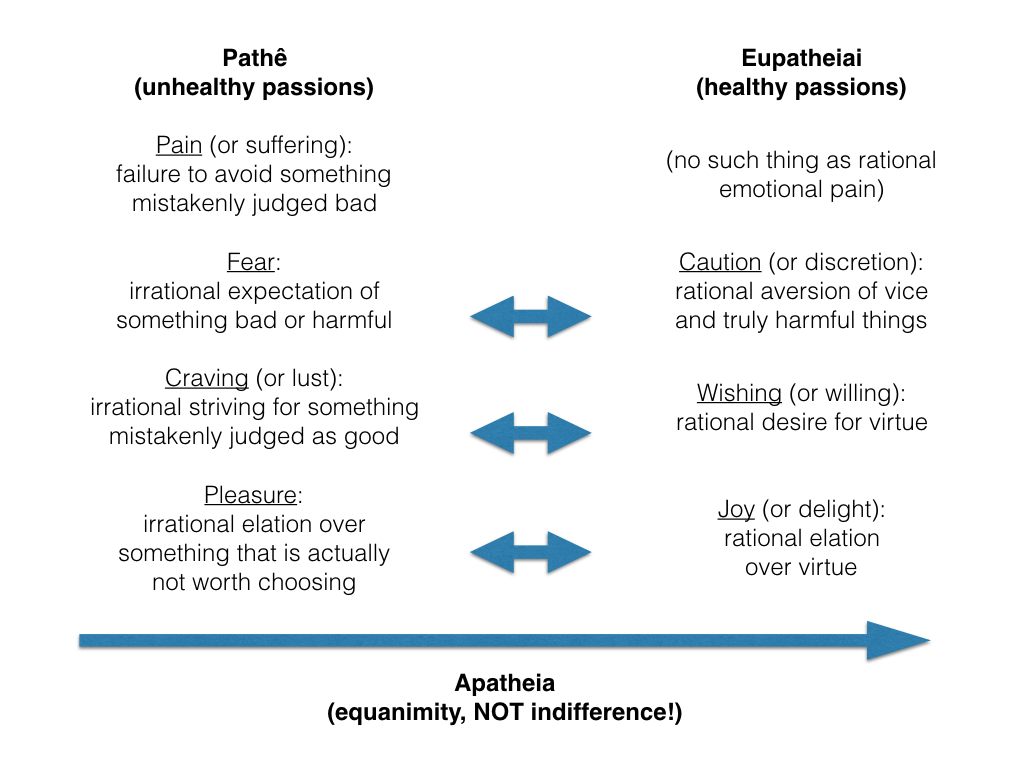

As far as the Stoics are concerned, however, it is good to remember that “passion” did not mean what we now mean by that term, and indeed it did not even exactly overlap with the term “emotion” in the modern sense of the word. That is why it is grossly incorrect to say that the Stoics aimed at a passionless life, or at the suppression of emotions. Rather, the Stoics divided the “passions” into unhealthy and healthy ones. The first group included pain, fear, craving, and pleasure. The second one “discretion,” “willing,” and “delight.” The latter were the opposite of the first group, except for pain, which does not have a positive counterpart. Here is a summary diagram:

A diagram of the Stoic passions

For the Stoics, then, the “passions” are not automatic, instinctive reactions that we cannot avoid experiencing. Instead, they are the result of a judgment, giving “assent” to an “impression.” So even when you read a familiar word like “fear,” don’t think of the fight-or-flight response that is indeed unavoidable when we are suddenly presented with a possible danger. What the Stoics meant by “fear” was what comes after that: your considered opinion about what caused said instinctive reaction. The Stoics realized that we have automatic responses that are not under our control, and that is why they focused on what is under our control: the judgment rendered on the likely causes of our instinctive reactions, a judgment rendered by what Marcus Aurelius called the ruling faculty (in modern cognitive science terminology: the executive function of the brain).

The Stoic view of emotions finds very nice parallels in modern neuroscience. For instance, Joseph LeDoux (2015) makes the important, if often neglected, point that there is a difference between what neuroscientists mean by “emotion” and what psychologists mean. Neuroscientifically, fear, for example, is the result of a defense and reaction mechanism that is involuntary and nonconscious, and whose major neural correlate is the amygdala. But what psychologists refer to when they talk of “fear” is a more complex emotion, constructed in part of the basic defense and reaction mechanism, to which the conscious mind adds cognitive interpretation, something very similar to the Stoic concept. The two meanings are not in contradiction, but are rather complementary. The cognitive interpretation of the raw emotion of fear, then, is brought about by a combination of one’s memories, cultural upbringing, deliberative thinking, and so forth. The Stoics clearly referred to the psychological, not the neuroscientific meaning of emotion as “passions,” and LeDoux’s own research seems to support the Stoic account and the practicability of their discipline of assent, seen in the previous section.

Going back to the above diagram: pain is not the simple sensation of pain, but the failure to avoid something that we mistakenly judge bad. Similarly for the other pathê: fear is the irrational expectation of something bad or harmful; craving is the irrational striving for something mistakenly judged as good; and pleasure is the irrational elation over something that is actually not worth choosing. Contrariwise, the eupatheiai are the result of a rational aversion of vice and harmful things (discretion), a rational desire for virtue (willing), and a rational elation over virtue (delight). (It should be clear now why there is no such thing as a rational emotional pain.)

All of the above is why apatheia is best construed as equanimity in the face of what the world throws at us: if we apply reason to our experience, we will not be concerned with the things that do not matter, and we will correspondingly rejoice in the things that do matter.

There is another crucial difference between the two schools to be highlighted here: they get to apatheia/ataraxia by very different routes. The Epicureans sought ataraxia as a goal, achieved most of all through the avoidance of pain, which meant especially to withdraw from social and political life. It was good, for Epicurus, to cultivate your close friendships, but attempting to play a full role in the polis was a sure way to experience pain (physical or mental), and therefore it was to be avoided. For the Stoics, on the contrary, the goal was the exercise of virtue, which led them to embrace their social role. Marcus Aurelius, for instance, constantly writes in the Meditations that we need to get up in the morning and do the job of a human being, which he interprets to mean to be useful to society. Hierocles elaborated on the Cynic/Stoic concept of cosmopolitanism. The motto of the school was “follow nature,” by which it was meant, as we have seen, the human nature of a social animal capable of rational judgment. And of course one of the four virtues examined in the previous section is justice, and one of the three disciplines is that of action—both explicitly prosocial. Apatheia, then, was not a goal for Stoics, but an advantageous byproduct (a preferred indifferent, so to speak) of living the virtuous life.

5. Stoicism after the Hellenistic Era

As Long (2003) has remarked, Stoicism has had a pervasive, yet largely unacknowledged influence on Western philosophical thought throughout the Middle Ages, Renaissance, and into modern times. Among the philosophers that he lists as being directly or indirectly affected by Stoicism are Augustine, Thomas More, Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Rousseau, Adam Smith, and Kant, to which we can easily add David Hume. During the Renaissance both Stoic books, particularly Epictetus’ Enchiridion and Seneca’s Letters, and books favorable to Stoicism, like Cicero’s De Officiis, were widely read.

Christianity was far more sympathetic to Stoicism than to its main rival, Epicureanism (and it also absorbed elements of Platonism in its “neo” form). The Epicurean emphasis on pleasure, as well as their metaphysics of cosmic chaos, where prima facie incompatible with Christian theology. The case of Stoicism was more complex. On the one hand, the Stoic insistence on materialism and pantheism was criticized and rejected; on the other hand, the idea of the Logos could easily be adapted—if in a fashion that the Stoics themselves would not have recognized—and the emphasis on virtue was often seen as pretty much the best that people could manage before the coming of Christ.

This is why we find an interestingly mixed record of Christian attitudes toward Stoicism. Augustine initially wrote favorably about it, while later on he was more critical. Tertullian was positively inclined toward Stoicism, and versions of the Enchiridion were commonly used (with Paul replacing Socrates) in monasteries. Peter Abelard and John of Salisbury were influenced by Stoic ethics too, while Thomas Aquinas was critical, especially of an early attempt at reviving Stoicism made by David of Dinant at the beginning of the 13th century.

A major revival of Stoicism did eventually take place, during the Renaissance, largely because of the work of Justus Lipsius (1547-1606). He was a humanist and classic philologist who published critical editions of Seneca and Tacitus. His major opus was De Constantia (1584), where he argued that Christians can draw on the resources of Stoicism during troubled times, while at the same time carefully pointing out aspects of Stoicism that are unacceptable for a Christian. Lipsius also drew on Epictetus, whose Enchiridion had first been translated in English a few years earlier. Other Neostoics included the French statesman Guillaume Du Vair, the churchman Pierre Charron, the Spanish author Francisco de Quevedo, and most importantly Michel de Montaigne, who wrote one of his essays in defense of Seneca.

The reception of Neostoicism was mixed. Even before Lipsius, Calvin had strongly criticized the “novi Stoici” for their revival of the idea of apatheia, and later critics included Pascal. In part in order to preempt such reactions, according to Sellars, one of the Neostoic texts began with the following cautious endorsement: “philosophie in generall is profitable unto a Christian man, if it be well and rightly used: but no kinde of philosophie is more profitable and neerer approaching unto Christianitie than the philosophie of the Stoicks.” Despite the interest in Stoicism displayed by other Renaissance figures, even outside of philosophy (for example, the poet Petrarch), Neostoicism never really became a movement, and its import largely rests on the impact of Lipsius’ writings, and perhaps on the influence of Montaigne.

Arguably the most important modern philosopher to be influenced by Stoicism is Spinoza, who was in fact accused by Leibniz to be a leader of the “sect” of the new Stoics, together with Descartes (Long 2003). There are indeed a number of striking similarities between the Stoic conception of the world and Spinoza’s. In both cases we have an all-pervasive God that is identified with Nature and with universal cause and effect. While it is true that the Stoic understanding of the cosmos was essentially dualistic—in contrast with Spinoza’s monism—the Stoic “active” and “passive” principles were nonetheless completely entwined, ultimately yielding an essentially unitary reality. Long points out, however, that a major difference was Spinoza’s concept of God’s infinite attributes and extension, in marked contrast to the finite (if eternal) God of the Stoics: “the upshot of both systems is a broadly similar conception of reality—monistic in its treatment of God as the ultimate cause of everything, dualistic in its two aspects of thought and extension, hierarchical in the different levels or modes of God’s attributes in particular beings, strictly determinist and physically active through and through.” He goes on to remark that the similarities are even more marked in terms of ethics, and “Spinoza’s ethics becomes transparently and profoundly Stoic.” That said, another major difference is that Spinoza did not believe in an underlying teleology to the world. For him Nature has no aim and God does not direct the cosmic drama. Indeed, as Long puts it: “If the Stoics had taken Spinoza’s route of denying divine providence, they would have avoided a battery of objections brought against them from antiquity onward.” In an important sense, perhaps, one can think of Spinoza as updating the Stoic system to modern times, a project that is currently seeing a number of concerted efforts.

Finally, there is also a connection between the Stoics and Kant, particularly in their shared concept of duty which transcends the specific consequences of one’s action. But as Long again points out, the differences are also quite striking: while Kant arrived at his system by a priori reasoning, the Stoics were eminently naturalistic and empiricist at heart. This is a major distinction between a deontological system like Kant’s and a eudaemonistic one like the Stoic, and it is only with the recent resurgence of virtue ethics in contemporary philosophy (Foot 1978, 2001; MacIntyre 1981/2013; Nussbaum 1994) that the ground was laid out for yet another revival of Stoicism as a practical moral philosophy.

6. Contemporary Stoicism

The 21st century is seeing yet another revival of virtue ethics in general and of Stoicism in particular. The already mentioned work by philosophers like Philippa Foot, Alasdair MacIntyre, and Martha Nussbaum, among others, has brought back virtue ethics as a viable alternative to the dominant Kantian-deontological and utilitarian-consequentialist approaches, so much so that a survey of professional philosophers by David Bourget and David Chalmers (2013) shows that deontology is (barely) the leading endorsed framework (26% of respondents), followed by consequentialism (24%) and not too far behind by virtue ethics (18%), with a scatter of other positions gathering less support. Of course ethics is not a popularity contest, but these numbers indicate the resurgence of virtue ethics in contemporary professional moral philosophy.

When it comes more specifically to Stoicism, new scholarly works and translations of classics, as well as biographies of prominent Stoics, keep appearing at a sustained rate. Examples include the superb Cambridge Companion to the Stoics (Inwood 2003), individual chapters of which have been cited throughout this entry; an essay on the concept of Stoic sagehood (Brouwer 2014); a volume on Epictetus (Long 2002); a contribution on Stoicism and emotion (Graver 2007); the first new translation of Seneca’s letters to Lucilius in a century (Graver and Long 2015); a new translation of Musonius Rufus (King 2011); a biography of Cato the Younger (Goodman 2012); one of Marcus Aurelius (McLynn 2009); and two of Seneca (Romm 2014 and Wilson 2014); and the list could continue.

In parallel with the above, Stoicism is, in some sense, returning to its roots as practical philosophy, as the ancient Stoics very clearly meant their system to be primarily of guidance for everyday life, not a theoretical exercise. Indeed, especially Epictetus is very clear in his disdain for purely theoretical philosophy: “We know how to analyze arguments, and have the skill a person needs to evaluate competent logicians. But in life what do I do? What today I say is good tomorrow I will swear is bad. And the reason is that, compared to what I know about syllogisms, my knowledge and experience of life fall far behind” (Discourses, II.3.4-5). Or consider Marcus’ famous injunction: “No longer talk at all about the kind of man that a good man ought to be, but be such” (Meditations, X.16).

The Modern Stoicism movement traces its roots to Victor Frankl’s (Sahakian 1979) logotherapy, as well as to early versions of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, for instance in the work of Albert Ellis (Robertson 2010). But Stoicism is a philosophy, not a therapy, and it is in the works of philosophers such as William Irvine (2008), John Sellars (2003), and Lawrence Becker (1997) that we find articulations of 21st century Stoicism, though the more self-help oriented contribution by CBT therapist Donald Robertson (2013) is also worthy of note. All of these authors attempt to distance the philosophical meaning of “Stoic”—even in a modern setting—from the common English word “stoic,” indicating someone who goes through life with a stiff upper lip, so to speak. While there are commonalities between “Stoic” and “stoic,” for instance the emphasis on endurance, the latter is a diminutive version of the former, and the two should accordingly be kept distinct.

Perhaps the most comprehensive and scholarly attempt to update (as opposed to simply explain) Stoicism for modern audiences comes from Becker (1997), though a more accessible treatment is offered by Irvine (2008). One of Irvine’s major contributions is shifting from Epictetus’ famous dichotomy of control to a more reasonable trichotomy: some things are up to us (chiefly, our judgments and actions), some things are not up to us (major historical events, natural phenomena), but on a number of other things we have partial control. Irvine recasts the third category in terms of internalized goals, which makes more sense of the original dichotomy. Consider his example of playing a tennis match. The outcome of the game is under your partial control, in the sense that you can influence it; but it is also the result of variables that you cannot control, such as the skill of your opponent, the fairness of the referee, or even random gusts of wind interfering with the trajectory of the ball. Your goal, then, suggests Irvine, should not be to win the game—because that is not entirely within your control. Rather, it should be to play the best game you can, since that is within your control. By internalizing your goals you can therefore make good sense of even the original Epictetean dichotomy. As for the outcome, it should be accepted with equanimity.

Becker (1997) is more comprehensive and even includes a lengthy appendix in which he demonstrates that the formal calculus he deploys for his normative Stoic logic is consistent, suggesting also that it is complete. There are three important differences between his New Stoicism and the ancient variety: (i) Becker defends an interpretation of the inherent primacy of virtue in terms of maximization of one’s agency, and builds an argument to show that this is, indeed, the preferred goal of agents that are relevantly constituted like a normal human being; (ii) he interprets the Stoic dictum, “follow nature” as “follow the facts” (that is., abide by whatever picture of the universe our best science allows), consistently with Stoic sources attesting to their respect for what we would today call scientific inquiry, as well as with an updated Stoic approach to epistemology; and (iii) Becker does away with the ancient Stoic teleonomic view of the cosmos, precisely because it is no longer supported by our best scientific understanding of things. This is also what leads him to make his argument for virtue-as-maximization-of-agency referred to in (i) above. Whether Becker’s (or Irvine’s, or anyone else’s) attempt will succeed or not remains to be seen in terms of further scholarship and the evolution of the popular movement.

That movement has grown significantly in the early 21st century, manifesting itself in a number of forms. There is a good number of high quality blogs devoted to practical modern Stoicism. There is also a significant presence on social networks, for instance the Stoicism Group on Facebook.

7. Glossary

The Stoics were well known (some would say infamous) for having developed a rich technical vocabulary. Cicero, in book III of De Finibus, explicitly says that Zeno invented a number of new terms, and he feels that Latin is not a sufficiently sophisticated tongue to render all the subtleties of Greek thought. Below are some of the major Stoic terms and their meanings.

Andreia = courage, fortitude, one of the four Stoic cardinal virtues.

Apatheia = tranquility, overcoming disturbing desires and emotions.

Apoproēgmena = dispreferred indifferents, externals, outside of virtue that—other things being equal—should be avoided.

Aretê = virtue, excellence at one’s function. For Becker this is equivalent to the perfection of agency.

Ataraxia = absence of fear, largely an Epicurean concept, but also adopted by the Stoics.

Dikaiosynê = justice, integrity, one of the Stoic cardinal virtues.

Eu̯dai̯monía = flourishing, by means of living an ethical life.

Eupatheiai = the healthy passions cultivated by the Sage.

Hormê = the discipline of action.

Kathēkon = appropriate, rational, action, the thing one ought to do.

Logos = rational principle governing the universe.

Oikeiôsis = something properly yours, leading to Hierocles’ circle of expanding affection, Stoic cosmopolitanism.

Orexis = the discipline of desire.

Philanthrôpia = love of mankind, related to the concept of Oikeiôsis.

Phronȇsis = practical wisdom, one of the Stoic cardinal virtues.

Proēgmena = preferred indifferents, externals, outside of virtue that—other things being equal—can be pursued unless they compromise one’s virtue.

Propatheiai = involuntary emotional reactions, to which one has not yet given or withdrawn assent.

Prosochê = applying key ethical precepts to the present moment, mindfulness.

Sôphrosynê = self-discipline, temperance, one of the Stoic cardinal virtues.

Sunkatathesis = the discipline of assent.

8. References and Further Readings

- Algra, K. (2003) Stoic theology. In: B. Inwood (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to the Stoics. Cambridge University Press.

- Almeder, R. (1995) Externalism and justification. Philosophia 24:465-469.

- Angere, S. (2007) The defeasible nature of coherentist justification. Synthese 157:321-335.

- Beaney, M. (1997) The Frege Reader. Blackwell.

- Becker, L.C. (1997) A New Stoicism. Princeton University Press.

- Bobzien, S. (2003) Logic. In: B. Inwood (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to the Stoics. Cambridge University Press.

- Bobzien, S. (2006) Ancient logic. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/logic-ancient/ (accessed on 22 December 2015)

- Bourget, D. and Chalmers, D.J. (2013) What do philosophers believe? Philosophical Studies 3:1-36.

- Brennan, T. (2003) Stoic moral psychology. In: B. Inwood (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to the Stoics. Cambridge University Press.

- Broadie, S. & Rowe, C. (eds.) (2002) Aristotle — Nicomachean Ethics. Oxford University Press.

- Brouwer, R. (2014) The Stoic Sage: The Early Stoics on Wisdom, Sagehood and Socrates. Cambridge University Press.

- Brunschwig, J. (2003) Stoic metaphysics. In: B. Inwood (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to the Stoics. Cambridge University Press.

- Bugh, G.R. (1992) Athenion and Aristion of Athens. Phoenix 46:108-123.

- Cicero, C.T. (2014) Complete Works. Delphi Classics.

- Colish, M. (1985) The Stoic Tradition from Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages. E.J. Brill.