Briefing: Children's rights - Spare the rod (April 1994) (original) (raw)

Socialist Review, April 1994

Children’s rights

Spare the rod

From Socialist Review, No. 174, April 1994.

Copyright © Socialist Review.

Copied with thanks from the Socialist Review Archive.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for ETOL.

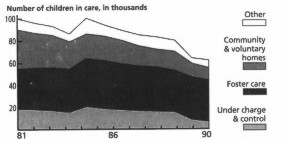

Type of accomodation for children in care

- Last month the High Court upheld a childminder’s right to smack children in her care. Yet article 19 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, ratified by the British government in 1991, obliges states to prevent physical violence to a child by parents and carers.

- Smacking and other forms of corporal punishment have been illegal in British state schools since 1986. Children from five years upwards are protected by law from being hit by professionals – pre-school children are not. If an adult were treated in such a way the assailant could be charged with assault.

- Child psychiatrists, other health professionals, educationalists and the vast majority of childminders are against smacking, purely because there is no evidence to show that it helps in disciplining children.

- Claire Rayner, the popular ‘agony aunt’, is a vocal opponent of smacking. She feels that ‘hitting children to discipline them just makes them angry and resentful. People do it because they think it’s quicker and easier than teaching the child.’

- Most local authorities in Britain expect their childminders to refrain from smacking, and have introduced guidelines and training courses to deal with issues of discipline. However there is no legislation to prevent childminders smacking children in their care.

- The Children Act which came into force in 1991 says that a local authority can refuse to register a childminder if they are ‘unfit’. Specific guidelines, including those on corporal punishment, are not legally part of the act, so they allow a loophole to the judges to uphold the right of childminders to smack.

- The Children Act is based on the notion that children’s welfare must come first. Yet subsequent laws such as the Child Support Act, the Education Reform Act, and the locking-up of 12-year-old offenders have clearly gone against this principle.

- We are often presented with the assumption that children have ‘never had it so good’. This could not be further from the truth. Many of today’s children live in conditions worse than those of the workhouses of Oliver Twist’s time.

- A recent National Children’s Home survey showed that for over 1.5 million families on income support, only £4.15 a week is allocated for food per child. This compares with weekly food allowances in workhouses of the equivalent of £7.07 per child in the early 1900s and £5.46 in the 1870s.

- Evidence from the National Children’s Bureau shows that there has been a huge increase in child poverty since 1979. A recent government report shows that nearly one in three children in Britain live in a family receiving less than half the average income. Linked to this poverty are poor health, unsatisfactory housing and inadequate educational opportunities.

- One in four children in London eat free school meals because of poverty. At school some children are unable to concentrate because of hunger, and teachers take in biscuits to feed their pupils.

- Poor child health is related to poverty, malnutrition and bad housing. The legacy of childhood illnesses often lasts throughout adult life. There has been an alarming increase in childhood asthma and other respiratory diseases particularly related to damp housing. Diseases related to chronic malnutrition, together with tuberculosis and rickets, are also making a comeback among children in Britain.

- Depression in childhood has been acknowledged only fairly recently. A survey published by the YMCA last month found 64 percent of teenagers questioned in Brighton had felt depressed at some time. The same study also found 58 percent of teenagers questioned had used illegal drugs.

- Children who suffer from neglect and abuse, or are considered ‘at risk’, are put on Child Protection Registers. Almost 50,000 children were placed on these registers in England and Wales during 1990. This works out at 3.7 per thousand children nationally. Comparing this figure with regional ones of 17.5 per thousand in deprived Southwark, south London, and 3 per thousand in nearby, but more prosperous, Bromley, we see some indication of the way poverty can affect families.

- In Strathclyde a fivefold increase in children registered as physically abused over five years in the late 1980s was directly attributed to an increased level of poverty in the region during the previous decade.

- The Children Act sets out that disadvantaged children should have their needs met by services provided for them by local authorities. Government cuts have meant new services are few and far between and existing ones are overstretched and underfunded.

- There is a massive demand for services that allow children to talk about their problems. Childline, a charity set up in 1986 to provide 24 hour telephone counselling, receives 10,000 calls every day, of which about 3,000 can be answered and only 200 to 300 dealt with in any depth.

- Teenagers surveyed in Brighton showed scepticism about local services – with lack of confidentiality, lack of understanding and poor availability being the major failings. One 16-year-old wanted services ‘just to be sympathetic to the needs of today’s young people, and understand when they feel stressed out about unemployment etc.’

Socialist Review Index | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 10 March 2017