Gallia Narbonensis - Gallo-Roman Museum of Lyon-Fourvi�re (original) (raw)

You may wish to see an introductory page to this section or a page on Roman Lyon first.

Plate from "Description du Mus�e lapidaire de la ville de Lyon par le Dr. Ambroise Comarmond 1846-1854": Sarcophagus of Bacchus/Dionysus in India

A museum was established in 1806 in a large deconsecrated abbey to house ancient inscriptions, fragments of architectural elements and sarcophagi. In 1854 its director published a detailed description of more than 700 items which were on display in the porticoes of building. In addition he listed 144 lost inscriptions which had been recorded by other writers. In the XIXth century the practice of using former churches or convents as sites for storing ancient materials was common in many towns of France, e.g. at Vienne, Avignon and Narbonne, as well as in Spain and in Italy.

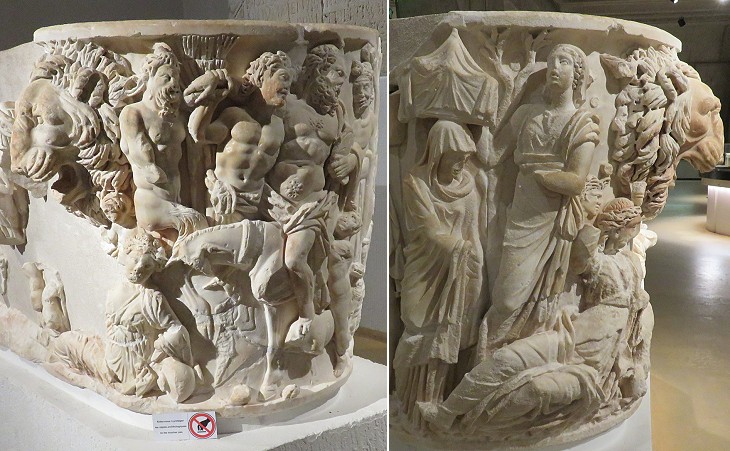

Gallo-Roman Museum of Lyon-Fourvi�re: Sarcophagus of Bacchus in India or of the Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne (early IIIrd century AD) found at Saint-Ir�n�e; notice drunken Hercules on the right (see him in a mosaic from Vienne)

Dr. Comarmond gave a lengthy description of how this sarcophagus was found during the reconstruction of a church and of how in 1824 it was carefully moved to the museum. The space given to it in the book shows that it was regarded as the finest exhibit of the collection. It is now a must-see of the Gallo-Roman Museum of Lyon-Fourvi�re which was inaugurated in 1975 near the archaeological area of the Great Theatre. Many other items described by Dr. Comarmond however were not deemed important enough to be housed in the new museum and are not visible to the public. Since then this tendency towards not encumbering the minds of visitors with too many things to see has become the rule in the design of new or redesign of old archaeological museums (e.g. at Antalya).

Sarcophagus of Bacchus in India: (left) one of the short sides showing a satyr and a maenad, a female follower of Bacchus; (right) detail of the main relief portraying Indian prisoners in the same way as Moor cavalrymen were depicted on Trajan's Column in Rome

| Nunc quoque qui puer es, quantus tum, Bacche, fuisti,Cum timuit thyrsos India victa tuos?Ovid - Ars Amatoria - Book I | Bacchus, who even now art a boy, how mighty wast thou then,when conquered India dreaded thy thyrsi!Translation by Henry T. Riley |

|---|

According to tradition Bacchus defeated the Indians because their elephants were scared by the noise made by his followers with their thyrsi (staffs) and by the braying of the donkey of Silenus, the tutor and companion of Bacchus.

Dr. Comardin suggested a Greek origin for the sarcophagus which instead was made in Italy because its marble is from Luni (Carrara). The Triumph of Bacchus after his victory in India was a very popular tale in many parts of the Roman Empire (see mosaics in Algeria, Tunisia and Spain and a jewel at the Louvre Museum).

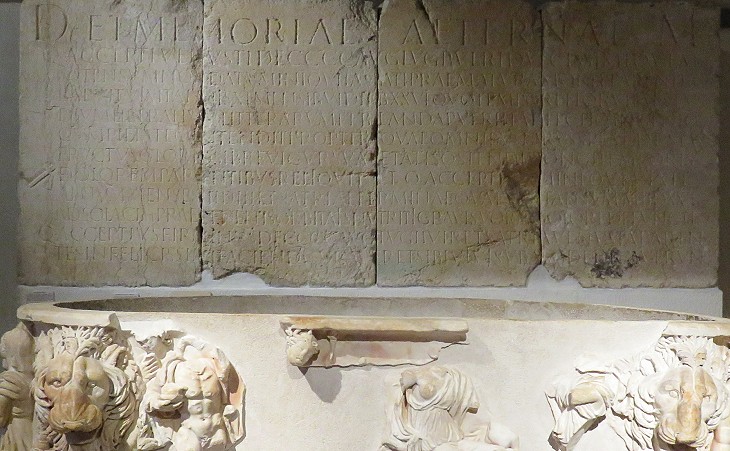

Mausoleum of Q. Acceptius Venustus: inscription and fragments of a sarcophagus which were found there

In 1870 a mausoleum was found in the outskirts of Lyon along the road which led to Vienne. It contained a long dedicatory inscription to a boy of eleven; his parents grieved also the loss of two other children. The inscription ends with the words sub ascia dedicavit which is peculiar of the Lyon region where it was found in more than 400 cases (see another inscription). Ascia is a small axe and it was also often carved on sarcophagi. The meaning of the sentence has been debated at length: according to the prevailing opinion it indicates total possession of the tomb and therefore it would be a sort of warning not to enter or damage it.

Details of the sarcophagus (early IIIrd century AD) found in Acceptius' mausoleum

The front of the sarcophagus most likely depicted the wedding of Bacchus of Ariadne; the curved parts show on one side Silenus on a donkey and on the other side an initiation rite in which a character goes under a phallus covered by a cloth. These subjects might seem not appropriate for the sarcophagus of a boy, but they had a hidden meaning of victory over death since Bacchus/Dionysus was the born-twice god, because after having been killed when he was a baby by order of Hera, he was recreated by Zeus out of his thigh. Dionysiac themes very often decorated sarcophagi; they might realistically depict scenes of drunkenness or portray children acting as satyrs and maenads, but in both cases they were a metaphor for some form of afterlife (see a page on the manufacture and trade of sarcophagi in the Roman Empire with other examples of Dionysiac subjects).

Worship of Mercury: (left/centre) Museum of Lyon; (right) Museum of Bonn

The name of the museum was recently modified into Lugdunum, the ancient name of the town. The original denomination of Gallo-Roman Museum was more indicative of its contents as it stressed the blending between the native culture with the Roman one. An aspect of this cultural intercourse can be noticed in the worship of Mercury, god of trade for the Romans and thus worshipped by the merchants who lived in Lyon. In many inscriptions in Gaul and Germany he was associated with local deities, in particular with Cissonius, Cernunnos, Gebrinus (as at Bonn) and Visucius. See other altars/statues of Mercury at Bordeaux, Perigueux, Augsburg, Trier and Cirencester.

(left/centre) God of Coligny; (right) Neptune (IInd century AD - found in the River Rh�ne in town)

In 1897 400 fragments of a bronze statue were found together with those of a calendar in a field near Coligny, north of Lyon. They were most likely temporarily hid to be sold to a foundry at a later moment, because there were no ancient buildings in the area. The statue was reconstructed, perhaps emphasizing its resemblance with Apollo; it was eventually labelled as the Mars of Coligny because a bronze inscription to Marti Augusto was found at Antre in the Jura mountains and it was thought that the two findings could be linked. Today it is more generically known as the God of Coligny.

A bronze statue found at Lyon in 1859 was associated with Neptune and it was most likely made for a guild of boatmen, similar to a marble statue of the god which was found at Arles.

Fragments of bronze statues of horses and of a bull

That of Neptune is the only entire bronze statue which was found in Lyon, but the Roman town had at least two bronze equestrian statues and it is thought they were made in a local foundry, because some of their details are less finely executed than in works made in Italy, e.g. the bronze statue of Emperor Marcus Aurelius.

(left) Votive relief portraying three Mothers or Matrons; (right) fragment of relief assumed to portray Mithra

The number three had a particular significance in all ancient religions including that of the Gauls; in this relief the number is combined with the worship of fertility goddesses; that at the centre holds a baby, those at her side have a patera, i.e. a votive offering and a cornucopia, a symbol of plenty. Similar reliefs have been found in Britain near Cirencester and at Cologne, but the practice of votive offerings with reliefs/statues portraying mothers was widespread in the Ancient World (see the statues of Mater Matuta at Capua and a relief of Demeter, Kore and Hecate at Selinunte).

A dedicatory inscription to Mithra was found in a location (today's Rue des Farges) which was close to Roman barracks: we know that the god was very popular among soldiers and many reliefs/statues portraying him have been found in German towns where the legions were stationed.

Funerary masks ("larvae") representing the spirits of the dead ("lemures") from a necropolis of Lyon (see similar ones at Cologne and Vaison)

Larvae and lemures are Latin words which today have a new meaning. In origin larvae meant masks and lemures the souls of those who had not been properly buried or had been killed. Some large rather dramatic funerary masks symbolizing the vengeful souls of the dead were placed around tombs at Lyon; their purpose was to protect the tombs, similar to reliefs portraying Gorgons or sub ascia inscriptions.

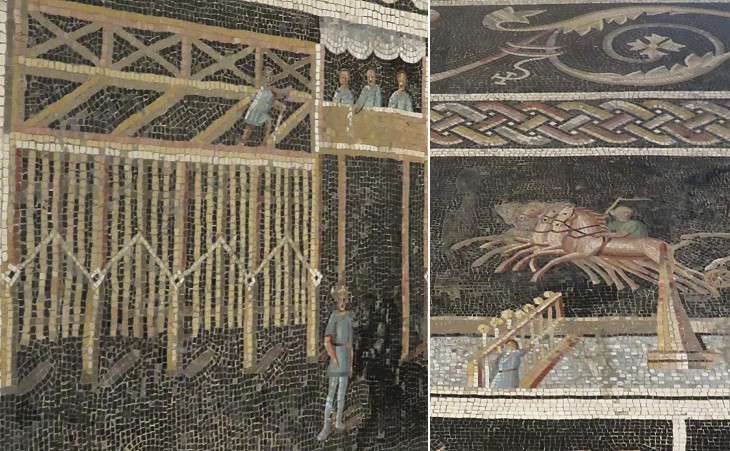

Relief depicting a chariot race and the "metae", turning points, of a circus

This fine relief was most likely part of a funerary monument. It might have belonged to a charioteer because we know that they could earn very well and therefore be in a position to pay for a fine tomb as did Publius Aelius Gutta Calpurnianus in Rome. The relief shows a race of bigae, two-horse chariots (as in a fresco at Ostia), although the more spectacular races were reserved to quadrigae, four-horse chariots. Archaeologists believe that the site of the circus of Lyon was located on the hill of Fourvi�re, but its remains have not yet been identified with certainty.

Circus Games Mosaic (IInd century AD) found to the south of Place Bellecour

Lugdunum was made up of the original Roman town on the hill of Fourvi�re, of the Gallic settlement at Contade and of a third neighbourhood on a flat peninsula between the two rivers (today's Presqu'Ile). Presumably it was where those who worked at the river harbours and warehouses lived, but archaeologists have found also evidence of rich houses. In 1806 a large floor mosaic was discovered there; it depicted in great detail a quadriga race in a circus. Unlike other similar mosaics it did not contain a clear reference to Circus Maximus; we know that the circus of Vienne had a pyramid, similar to that shown in this mosaic.

Circus Games Mosaic: (left) four of the eight "carceres" (starting boxes); (right) system for counting the number of laps

Mosaics and reliefs have provided archaeologists and historians with a visual idea of an actual Roman chariot race and of the monuments, facilities and devices which existed in a circus. In this mosaic we have a clear understanding of how the carceres were opened at the same time by pulling a lever and of how the raising of poles told the spectators the number of remaining laps. In this respect this mosaic is more accurate than other large mosaics, e.g. those found in Sicily, at Girona and Barcelona. Another interesting aspect is that it depicts a certamen binarium, i.e. one in which each of the four factions (Reds, Blues, Greens and Whites) compete with two chariots, while the other mosaics show only one chariot per faction.

Mosaic of Dionysus and the Four Seasons (IInd/IIIrd century AD; found in town in 1911)

This floor mosaic contains an elaborate geometric frame which reminds of the Labyrinth, the maze of Knossos, and is characterized by swastikas aka [Greek key patterns](Glossar3.html#Greek key pattern) having many symbolic meanings, including the flow of time. This concept is expressed also by the Four Seasons. Dionysus is portrayed in a very relaxed pose, laying on a panther as if it were a couch for a banquet; most probably the mosaic decorated the floor of a triclinium, the Roman dining room.

Detail of the mosaic of the Fight between Cupid and Pan (IIIrd century AD - found in town)

The fight symbolizes the conflict between love (Cupid) and sheer sexual desire (Pan) and it can be seen also in a famous statue of Venus with Cupid and Pan which was found at Delos. The overreaching power of Cupid was chanted by Virgil (Omnia vincit Amor, Love conquers All) and by Ovid. The mosaic depicts a formal contest with an umpire (Silenus) holding the palm of victory and Pan fighting with a hand behind his back (because he is an adult and Cupid a child). The same scene can be seen in mosaics at Ostia and in Sicily.

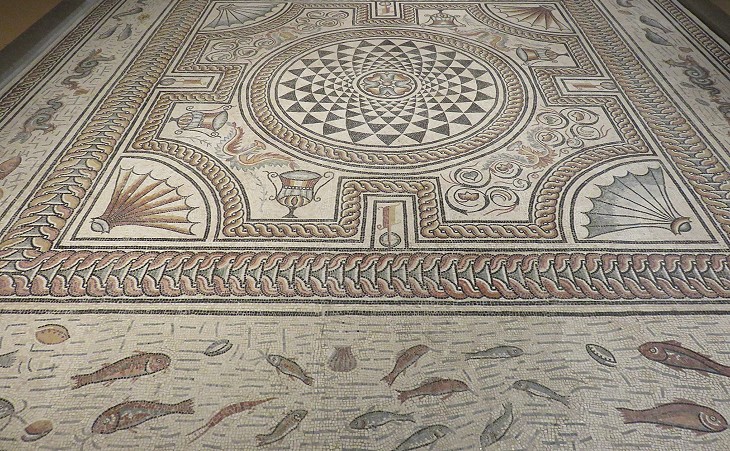

Mosaic of the Fish (IIIrd century AD - found in town in 1843)

A catalogue of sea creatures might not have been a subject very suitable for a house of Lyon, but it was in high fashion in many parts of the Roman Empire (see impressive mosaics in Tarragona and Antioch) and Lyon had a cosmopolitan population. In this mosaic the sea creatures were depicted in a side band whereas most of the mosaic had an elaborate decoration which included a central "vortex" optical effect (see it better in a mosaic in Tunisia).

Large geometric mosaic (IIIrd century AD - found in town in 1913)

The size and the type of decoration of this mosaic prove that the Roman process for flooring was based on sound techniques which ensured its durability. The straight bands which created 91 squares of the same size in this mosaic would have rapidly shown signs of deterioration if the underlying six layers of different materials had not been perfectly laid and the mortar had not been of excellent quality.

Fresco from Maison aux Xenia (Ist century AD - found in town in 1988)

In general we have by far more Roman floor mosaics than frescoes, but the exceptional circumstances which froze in time Herculaneum and Pompeii have shown that the walls of the houses were usually painted. This fresco was reconstructed from tiny fragments of paint from a demolished wall by using a technique which was not available until recent years. Xenia were the gifts in food and drinks which were made to guests (Greek xenos meaning foreigner/guest). These gifts were depicted also in floor mosaics of reception rooms, e.g. at Sepphoris; a particular type of xenia floor mosaic decorated Horti Serviliani in Rome.

The image used as background for this page shows a relief portraying Autumn in the museum.

Return to Roman Lyon or move to Vieux Lyon.