Venice and the Levant - Part one: the early development (original) (raw)

Foreword

These pages are meant to complement the section of this website dealing with the Venetian Fortresses in Greece, by showing some aspects of today's Venice which are linked to the role it had for centuries in Greece and more in general in the Levant.

These pages are not meant to provide a comprehensive description of the monuments of Venice or of its history.

Introduction

Stockholm and Amsterdam claim to be the Venice of the North and Bangkok the Venice of Asia: London has a Little Venice and so does Mykonos; a beach of Los Angeles is named after Venice. With due respect for those who have made these associations Venice can only be compared to itself (J. W. Goethe - Italian Journey - 1786).

View of Canal Grande (left) and of Rio di S. Barnaba (right)

Venice strikes the viewer as being so different from any other city: it seems the result of Creation, rather than Evolution and its late XVIIIth century appearance does not help in understanding when, why and how it was built.

Houses on a minor island of the lagoon

The natural environment the first inhabitants of Venice saw can still be perceived from a ferry going to Burano and Torcello in the northern end of the lagoon. Here one can see the islets of mud which were formed by the combined action of tides and of rivers coming from the Alps; they compose a marshy landscape covered by low vegetation; the huts of the first settlers were at the very edge of the water: the ground did not support the weight of masonry. Only by driving in piles by the thousands it was possible to lay foundations which could support a traditional building, so it is fair to say that Venice stands on an Alpine forest.

According to tradition Venice was founded in 421, but evidence of its existence dates from the VIth century: the first settlers wanted to escape the turmoil caused by the many conflicts which ravaged Italy. They were fishermen and to complement their economy they produced salt which they exchanged for other basic products. When Italy was partitioned between the Longobards and the Byzantines the lagoon was assigned to the latter: the link between Venice and Constantinople was established.

Byzantine Venice

View of Torcello

In the VIIIth century the Longobards occupied Ravenna and other Byzantine possessions in northern Italy; Venice and other locations of the lagoon remained subject to the almost nominal rule of Constantinople and did so also when the Franks replaced the Longobards.

One can guess the appearance of early Venice by looking at Torcello, a town which for some time competed with it; the main buildings were positioned at some distance from each other and the tall bell tower was not placed next to the church to which it belonged. This approach was followed in order to avoid collateral damage from a collapsing building. Tall buildings in particular were subject to progressive leaning and this explains why, unlike most of medieval Italian towns, the most important Venetian families of that period did not live in tower houses. Most of the bell towers of Venice significantly lean and that of S. Marco, the most imposing church of Venice, collapsed in 1902.

Torcello: (left) bell tower and rear view of the cathedral; (centre/right) S. Fosca: the narthex and the apse

The two churches of Torcello were completed in the XIth century and they show the influence of Byzantine art: all five naves of the cathedral end with an apse, S. Fosca has a Greek cross shape and is surrounded on three sides by a narthex, the cathedral had a baptistery (lost) included in its narthex, the capitals of the columns have a pulvino and the masonry decoration follows Byzantine patterns.

(left) Columns in Piazza S. Marco; (centre and right) Byzantine capital and statue of St. Theodore

The link between early Venice and the Greek world was also testified by the city's patron: St. Theodore of Amasea, a Greek military saint of the IVth century, to whom the Byzantines dedicated a [church in Rome](Vasi54.htm#S. Teodoro), near the residence of their governors. His iconography is very similar to that of St. George, another Greek military saint, with a crocodile replacing the dragon. In 992 the economic and military growth of Venice was recognized by Emperor Basil II who granted Venetian merchants important trading rights in return for the city's support to his campaigns against the Arabs. By that time Venice had developed trading routes for importing spices and pepper.

Mosaic showing the translation of St. Mark

According to the traditional account in 828 two merchants brought the body of St. Mark the Evangelist to Venice from Alexandria; they donated it to the city's supreme magistrate, the Doge (duke, the title given by the Byzantines to governors of their provinces). The Coptic Church claims that the head of the saint remained in Alexandria.

Most likely the devotion to St. Mark and his becoming the patron saint of Venice took place at a later period and was motivated by political reasons; Venice was "coming of age" and a Greek patron saint was not appropriate for a city which no longer relied on Byzantine protection for developing its trade. At the same time the choice of St. Mark was a sort of response to the claims of the Church of Rome: the popes included Venice in the territories they regarded as being under their suzerainty. St. Mark was seen as a shield towards St. Peter's expansion designs.

The body of the saint was placed in a church dedicated to him next to the residence of the Doge. An old mosaic, most likely designed by artists from Constantinople, shows the translation of the body and the appearance of the church at the end of the XIth century; it also portrays a very affluent society.

The Lion of St. Mark

The Venetians placed a statue of St. Theodore on one of the two tall granite columns they brought from the Levant: on the other they did not place a statue of St. Mark, but rather a statue of his symbol: a lion. The ancient bronze statue was modified and restored several times and both the wings and the long tail are thought to be later additions: the original parts show features of Assyrian/Persian art: most likely the lion was bought by Venetian merchants in Syria.

Domes of S. Marco

When the Venetians decided to build S. Marco they had in mind the two most celebrated churches of Constantinople: Hagia Sophia, at the time the largest church of the world; it was built by Emperor Justinian in 537 - a tall building with an impressive dome; or the Apostoleion, a Greek cross church (lost) with five domes where Emperor Constantine was buried. The Apostoleion was chosen which did not cause major static worries because of its weight.

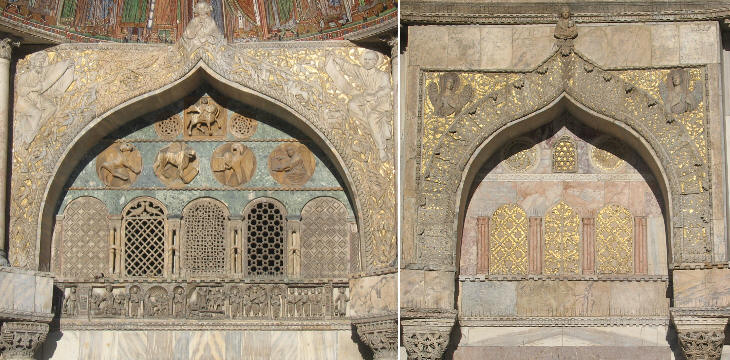

Two arches of the portico of S. Marco

Venetian merchants often travelled to Syria, the Holy Land and Alexandria: they were impressed by the flowing lines of Islamic art; this led to designing the arches of the portico in a way which shows the links Venice had with that part of the Levant (the image in the background of this page shows the shape of another arch).

See these other pages:

Venice and the Levant - Page two - A Powerful Player

Venice and the Levant - Page three - A Cosmopolitan City

Venice and the Levant - Page four - A Military Power

Venetian Fortresses in Greece