Soyuz 7K-OK spacecraft (original) (raw)

Soyuz 7K-OK variant

Compared to its predecessors -- Vostok and Voskhod -- the three-seat Soyuz offered enormous advantages. The most important feature of the new ship would be its rendezvous and docking system.

Previous chapter: Origin of the Soyuz project

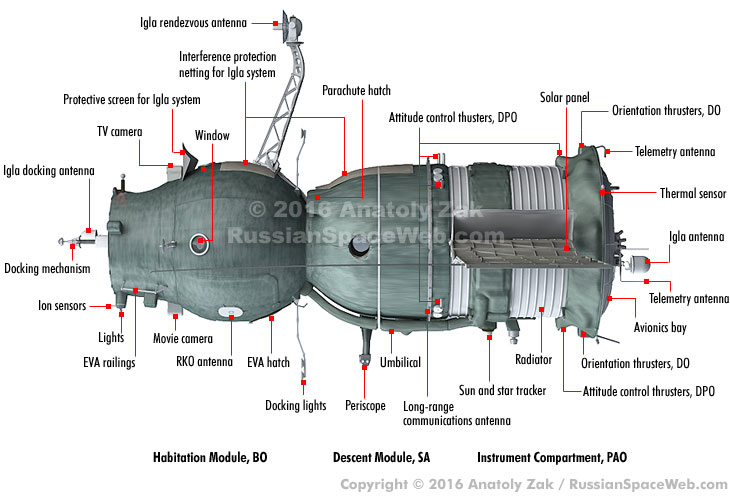

External design of the 7K-OK (Soyuz) spacecraft.

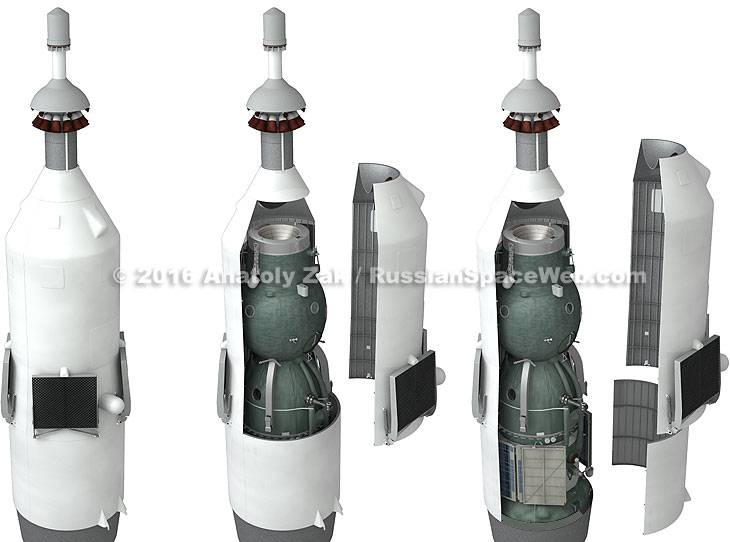

An upper composite configuration during the Dec. 14, 1966, attempt to launch the Soyuz 7K-OK No. 1 vehicle.

From the publisher: Pace of our development depends primarily on the level of support from our readers!

The Soyuz (7K-OK) spacecraft at a glance:

| Crew | 1 - 3 people |

|---|---|

| Mass after separation from the launch vehicle | 6.38 tons (2); 6,450 - 6,560 kilograms |

| Descent Module mass | 2,800 kilograms (52) (2,700 kilograms (84)) |

| Spacecraft body length | 7.6 meters (52) (7.54 meters (84)) |

| Spacecraft body diameter | 2.2 meters |

| Descent Module length | 2.16 meters |

| Spacecraft maximum diameter | 2.72 meters |

| Solar panels span | 8.37 meters |

| Total habitable volume of two pressurized compartments | 10.45 cubic meters (2) |

| Free habitable volume of two pressurized compartments | 6.5 cubic meters (2, 52) |

| Nominal flight duration | 3 - 10 days |

| Solar panel area | 14 square meters |

| Number of rendezvous and orientation thrusters, DPO | 14 (thrust: 10 kilograms) |

| Number of orientation thrusters, DO | 8 (thrust: 1.5 kilograms) |

| Number of descent control thrusters | 6 |

| Number of rendezvous and orbit correction thrusters | 2 |

| Initial parking orbit for "active" spacecraft during a joint flight | 202 by 222 kilometers |

| Initial parking orbit for "passive" spacecraft during a joint flight | 190-210 by 270-290 kilometers |

| Orbital period | 88.5 - 89 minutes |

| Orbital inclination | 51 degrees 43 minutes |

| Time required for rendezvous and docking of two spacecraft | No more than 65 minutes |

| First launch (unmanned) | 1966 Nov. 28 (Kosmos-133) |

| Total spacecraft launched | 16* (8 unmanned, 8 manned) |

Spacecraft design

The capability of spacecraft to link up in orbit promised to overcome the limitations of existing rockets by assembling bigger vehicles out of smaller components. Because the original design of the Soyuz complex envisioned the use of unmanned tankers, the new spacecraft inherited the fully automated Igla (needle) rendezvous system.

The Soyuz spacecraft also sported a newly developed habitation module, which provided most life-support functions for the crew, including a toilet, thus enabling much longer missions than those possible aboard Vostok. In addition, this ball-shaped habitation compartment could also double as an airlock for space walks. To perform the transfer of crew members between docked ships, the Soyuz carried new spacesuits. However, the developers chose not to equip crew members with protective suits inside the spacecraft, because Vostok and Voskhod missions had never experienced loss of pressure.

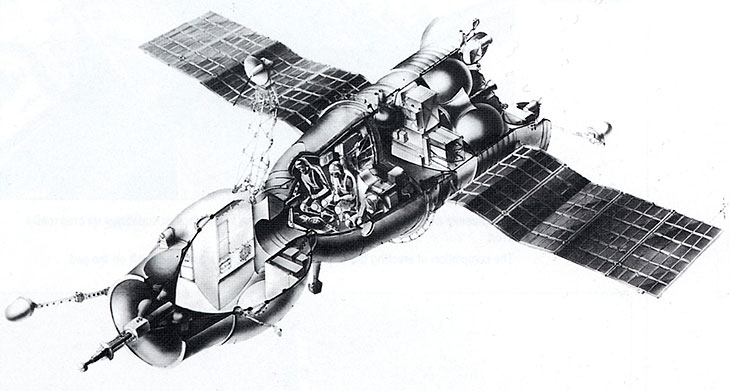

Internal design of the 7K-OK (Soyuz) spacecraft.

During the transition from Vostok to Soyuz, most of the existing internal systems developed for human space flight were radically reworked. Practically all the hardware was built on the principle that any failed component would have to be backed up by an alternative system, ensuring the safety of the crew.

The flight control system, developed at Department 27 led by Boris Raushenbach, could maintain orientation of the spacecraft in orbital and inertial coordinate systems and it could also place the vehicle in the correct attitude for orbital and deorbiting maneuvering, rendezvous and point its solar arrays toward the Sun.

For the first time in the Soviet space technology, the Descent Control System, SUS, could steer the descent capsule during its return to Earth and maintain the correct attitude to produce aerodynamic lift. As a result, the crew would enjoy a gentler descent, when compared to loads experienced by pilots aboard Vostok. Several groups of small thrusters were using pressure-fed highly concentrated hydrogen peroxide to maneuver the descent module.

Propellant tanks for the descent control thrusters were initially placed inside the crew capsule, but in 1964, Korolev found this arrangement too dangerous and the tanks were moved to a specially designed niche on the exterior of the module.

Instead of the single braking engine on Vostok capable of just one firing, the Soyuz received a brand-new dual-engine propulsion system, designed for multiple firings in space. The KTDU-35 propulsion system was conceived as an integrated unit comprised of propellant tanks, the main rendezvous and correction engine, SKD, and a two-chamber backup correction engine, DKD, which could be used for a braking maneuver in an emergency.

Soyuz also carried two groups of small thrusters with their own autonomous tanks: small engines, DO, which could be used for attitude control in orbit, and a group of larger engines, DPO, which had an additional rendezvous function.

The brand-new power supply system on Soyuz relied on a pair of solar panels feeding multiple rechargeable batteries.

The multi-functional communications system of the Soyuz spacecraft originally conceived for a lunar flyby missions, enabled the transmission of commands, TV signals and telemetry data, as well as voice communications. Radio signals could also be used to measure the orbital parameters of the ship.

By 1970, a total of 17 flight-worthy 7K-OK vehicles had been manufactured and from 1968, the Air Force was pushing for the production of 10 more such vehicles, however, the space directorate of the Soviet military, GUKOS, and the General Staff were skeptical about the role of piloted spacecraft in military operations. The Head of TsKBEM design bureau Vasily Mishin was also not enthusiastic, because the work on Soyuz was siphoning resources from the lunar project. (142) However, after the US won the Moon Race in 1969, the Soviet political priorities quickly shifted to the Earth-orbiting space station, making the Soyuz the best candidate for ferrying the crews to the orbital outposts.

Soyuz 7K-OK development responsibilities at OKB-1/TsKBEM:

| Responsibility | Department | Key official(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Original studies of the manned lunar flyby vehicle | 9 | M.K. Tikhonravov |

| Development of automated rendezvous methods | 27 | B.V. Raushenbakh |

| Analysis of atmospheric descent problems, crew capsule shape and emergency escape system | 11* | V.F. Roshin |

| Spacecraft structure design | 15 | G.G. Boldyrev |

| Structural material selection and analysis | 6 | N.G. Sidorov |

| Overall development | 3** | YaP. Kolyako |

*Based on a calculation group of Department 8 from Artillery design bureau TsNII-58, which was absorbed by OKB-1 in 1959. **After August 1963.

Key contractors in the Soyuz 7K-OK project:

| Responsibility | Developer | Key official(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Prime developer | OKB-1 | Sergei Korolev, Aleksei Topol |

| Propulsion system, SKDU | OKB-2 | A.M. Isaev |

| Parachute for landing system, SP | NIEI PDS | F.D. Tkachev, N.A. Lobanov |

| Pilot console, landing and escape system testing | LII | N.S. Stroev, V.V. Utkin |

| Emergency Escape System, SAS | Zavod Iskra | I.I. Kartukov |

| Launch vehicle and payload section | OKB-1 Kuibyshev branch | D.I. Kozlov |

| Igla rendezvous system, echoless chambers | NII TP | A.S. Mnatsakanyan |

| Kontakt rendezvous system (alternative to Igla) | OKB MEI | A.F. Bogomolov |

| Motion and attitude control system simulator | KB SM, TsNIIAG | A.M. Shakhov, I.I. Pogozhev |

| Attitude control and rendezvous thrusters development support | GIPKh, TsNIITA | V.S. Shpak, Yu.B. Sviridov |

| Long-range communications and telemetry system, DRK | NII-885 | M.S. Ryazansky |

| Krechet TV system | VNII Television | I.A. Rasselevich |

| Zarya radio-communications system | MNII RS | Yu.S. Bykov |

| Mir-3 autonomous recording system | NII-88 | I.I. Utkin |

| Life-support and landing systems, toilet, water storage | Zavod 918 | S.M. Alekseev, G.I. Severin |

| Components of the thermal control and life-support system | NPO Nauka | G.I. Vornin |

| Food and medical kits | IMBP | V.I. Yazdovsky |

| Atmosphere gas analyzer | SKB AP | V.A. Pavlenko |

Missions of the Soyuz 7K-OK variant:

| - | Official name | Industry name | Launch date | Landing date | Launch vehicle | Crew | Mission summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kosmos-133 | 7K-OK No. 2 | Nov. 28, 1966 | Nov. 30, 1966 | Soyuz | Destroyed on reentry | |

| 2 | Unannounced | 7K-OK No. 1 | Dec. 14, 1966 | - | Soyuz | Destroyed on Pad 31 due to an accidental ignition of the emergency escape system, resulting in three fatalities. | |

| 3 | Kosmos-140 | 7K-OK No. 3 | Feb. 7, 1967 | Feb. 9, 1967 | Soyuz | Lost pressure and sunk in the Aral Sea during botched landing | |

| 4 | Soyuz-1 | 7K-OK No. 4 | April 23, 1967 | April 24, 1967 | Soyuz | Vladimir Komarov | Planned for docking with a second Soyuz. Developed problems in orbit. Crashed on landing killing Komarov |

| 5 | Kosmos-186 | 7K-OK No. 6 | Oct. 27, 1967 | Oct. 31, 1967 | Soyuz | Docked with Kosmos-188. Made ballistic return | |

| 6 | Kosmos-188 | 7K-OK No. 5 | Oct. 30, 1967 | Nov. 2, 1967 | Soyuz | Docked with Kosmos-186. Self-destructs on landing | |

| 7 | Kosmos-212 | 7K-OK No. 8 | April 14, 1968 | April 19, 1968 | Soyuz | Docked with Kosmos-213 | |

| 8 | Kosmos-213 | 7K-OK No. 7 | April 15, 1968 | April 20, 1968 | Soyuz | Docked with Kosmos-212 | |

| 9 | Kosmos-238 | 7K-OK No. 9 | Aug. 28, 1968 | Sept. 1 | Soyuz | Test flight | |

| 10 | Soyuz-2 | 7K-OK No. 11 | Oct. 25, 1968 | Oct. 28, 1968 | Soyuz | Rendezvous with Soyuz-3 | |

| 11 | Soyuz-3 | 7K-OK No. 10 | Oct. 26, 1968 | Oct. 30, 1968 | Soyuz | Georgy Beregovoy | Attempted to dock with Soyuz-2 but failed due to wrong orientation |

| 12 | Soyuz-4 | 7K-OK No. 12 | Jan. 14, 1969 | Jan. 17, 1969 | Soyuz | Vladimir Shatalov | Docked with Soyuz-5 |

| 13 | Soyuz-5 | 7K-OK No. 13 | Jan. 15, 1969 | January 18, 1969 | Soyuz | Boris Volynov, Yevgeny Khrunov, Aleksei Yeliseyev | Docked with Soyuz-4; Khrunov and Yeliseyev transferred to and landed onboard the Soyuz-4 |

| 14 | Soyuz-6 | 7K-OK No. 14 | Oct. 11, 1969 | Oct. 16, 1969 | Soyuz | Georgy Shonin, Viktor Kubasov | |

| 15 | Soyuz-7 | 7K-OK No. 15 | Oct. 12, 1969 | Oct. 17, 1969 | Soyuz | Anatoly Filipchenko, Viktor Gorbatko, Vladislav Volkov | Planned to dock with the Soyuz-8 |

| 16 | Soyuz-8 | 7K-OK No. 16 | Oct. 13, 1969 | Oct. 18, 1969 | Soyuz | Vladimir Shatalov, Aleksei Yeliseev | Planned to dock with the Soyuz-7, but docking system failed |

| 17 | Soyuz-9 | 7K-OK No. 17 | June 1, 1970 | June 19, 1970 | Soyuz | Andriyan Nikolaev, Vitaly Sevastyanov | Set a new flight-duration record |

Next chapter: Origin of the Soyuz 7K-OK variant

The article and illustration by Anatoly Zak; Last update:June 23, 2024

Page editor: Alain Chabot; Last edit: November 27, 2016

All rights reserved

Basic architecture of the 7K-OK spacecraft (in "active" configuration).

Artist depiction of the 7K-OK variant in "passive" configuration.

A demo of the Soyuz spacecraft with a passive docking port. Credit: MAI

Flight control console inside the original version of the Soyuz spacecraft. Click to enlarge Copyright © 2000 Anatoly Zak

Kazbek chair for the Soyuz spacecraft. Copyright © 2011 Anatoly Zak

Front section of the 7K-OK spacecraft with active docking port.

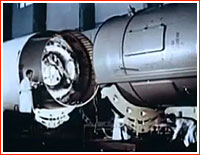

Soyuz 7K-OK spacecraft during pre-launch processing in Tyuratam.

A 7K-OK spacecraft is being fueled for launch.

A payload section with a 7K-OK spacecraft is being integrated with the third stage of the launch vehicle.

An early Soyuz spacecraft during final processing on the launch pad in Tyuratam. Credit: RKK Energia

Footage from the joint mission of Soyuz-4 and Soyuz-5 spacecraft in 1969 likely captured this view of departing Soyuz-4 spacecraft. Credit: Roskosmos

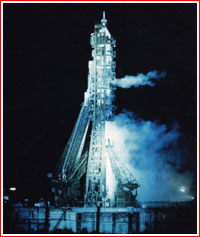

Launch of a Soyuz 7K-OK spacecraft.

)