Soyuz-5 (Feniks) rocket (original) (raw)

The author would like to thank Vladimir Shtanin, Igor Rozenberg and Claude Mourier for their help in preparing this section.

Searching for details:

The author of this page will appreciate comments, corrections and imagery related to the subject. Please contact Anatoly Zak.

Related pages:

Russia's new-generation rocket gets go ahead

Despite severe cuts in its space budget at the end of 2015, the Russian government gave the go ahead to the development of a new launcher family, which could finally replace the legendary Soyuz rockets after seven decades in service. Moreover, the new rocket was also positioned as a stepping stone toward the super-heavy booster to carry a next-generation manned spacecraft into deep space.

Previous chapter: Rus-M rocket

| - | Soyuz-5.0 | Soyuz-5.1 | Soyuz-5.2 | Soyuz-5.3 | Soyuz-5.3/PTK NP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payload to LEO | 3.0 tons | 9.0 tons | 16.5 tons | 26 tons | ? |

| Liftoff mass | 200.0 tons | 268.7 tons | 575.0 tons | 690.2 tons | ? |

The Soyuz-5 family of rockets as envisioned at the beginning of 2015 (left to right): Soyuz-5.0, Soyuz-5.1, Soyuz-5.2, Soyuz-5.3 and its man-rated version designed to carry the next-generation spacecraft, PTK NP. Copyright © 2016 Anatoly Zak / RussianSpaceWeb.com

The Soyuz-5 proposal

Russian officials did not hide the fact that the latest move was prompted in part by the competition from the US-based SpaceX company. "...Competitors are already stepping on our heels, look what's billionaire (Elon) Musk is doing with its projects!" Russian Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin told the Vesti TV channel on Dec. 30, 2015, "We are treating his work with respect and we are studying and analyzing it in detail," Rogozin said, "...we are looking for solutions which will make our space launches much cheaper and these solutions will be found... to maintain our leadership in the launch (services) market." Enter the methane rocket...

In 2013, engineers at TsSKB Progress in the Russian city of Samara began preliminary work on a new rocket series dubbed Soyuz-5. The new booster could cut cost of space transportation thanks to its reliance on new engines burning environmentally safe and widely available propellant made out of cryogenically cooled natural gas (or methane) instead of traditional kerosene fuel.

Soyuz-5 could eventually replace current rockets in the Soyuz family capable of delivering up to eight tons of payload to the low Earth orbit. Moreover, follow-on variants could carry 16 tons, thus replacing Zenit, and 25 tons, matching Proton in the current Russian fleet. Farther into the future, Soyuz-5 could pave the way to heavy and super-heavy rockets, as well as to low-cost reusable space boosters.

As of 2015, the price tag for a single launch of the Soyuz-5.1 variant, including the Fregat upper stage, was expected to be as low as $50 million to match or even outcompete the US Falcon rocket series on the international market.

However the Soyuz-5 rocket, which is still on the drawing board, overlaps the capabilities of the new-generation Angara family, which reached the launch pad in 2014. Still, engineers at TsSKB Progress were banking on the fact that a slowly emerging propulsion technology relying on methane would justify the development of at least an experimental rocket to prove the viability of the new fuel for future space launchers. Under such a scenario, the Soyuz-5 could serve as a precursor to a reusable booster stage in the next-generation space transportation system.

The idea of using low-cost, easy-to-maintain methane engines in futuristic returnable rockets have been considered for a number of years by various space powers around the world. Russia's current long-term strategy in rocket development does envision a partially reusable launch vehicle dubbed MRKS equipped with a winged booster stage. After lifting the second expendable stage of the MRKS vehicle into the stratosphere, the reusable booster would separate and glide back to Earth to be prepared for its next mission. Obviously, reliability and low cost of maintenance between flights would be critical for making such a vehicle economically viable. As a result, a traditional throw-away rocket designed to test innovative methane engines could serve as a bridge toward next-generation reusable boosters.

Despite being christened as a part of the Soyuz family, Soyuz-5 would look nothing like the classic space launcher that opened the space era. Instead, it would use a modular design enabling to form three or four rockets in different mass categories. The design of Soyuz-5 would also be adaptable for an entirely new class of heavy launchers. (653) TsSKB Progress was expected to bring Soyuz-5 concepts to any future tenders offered by Roskosmos for the development of launch vehicles to follow the Angara family.

| - | Soyuz-5.1 | Soyuz-5.2 | Soyuz-5.3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Payload mass | 8.5 tons | 16 tons | 25 tons |

| Liftoff mass | 252 tons | 577.7 tons | 643.5 tons |

| Number of stages | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Diameter of payload fairing | 4.11 meters | 4.35 meters | 4.35 meters |

| Maximum length | 50.1 meters | 46.7 meters | 56.7 meters |

Three variations of the Soyuz-5 rocket as of 2013 and 2014. Each module of the first stage would be equipped with a single RD-0164 engine burning liquid methane. An upper stage would feature RD-0124 engine modified for methane fuel and developing a thrust of 30 tons.

Advantages of methane fuel

Research into methane propulsion systems was led by Chemical Automatics Design Bureau, KBKhA, based in the city of Voronezh. The effort dates back to at least 1995. By that time it was established that the replacement of traditional kerosene with liquefied natural gas could produce a higher specific impulse -- the key performance characteristic of rocket engines. Moreover, liquid methane was estimated to cost up to 30 percent less than kerosene.

The cooling capability of methane is also three times higher than that of kerosene making it more effective as a coolant for the combustion chamber. Moreover, methane would leave no solid residue in the engine's fuel lines, excluding the need for a laborious cleaning before a new test or the delivery of an already tested engine for installation on the rocket. With performance characteristics equal to that of a kerosene engine, a methane propulsion system would require lower pressure in the combustion chamber and on the exit lines from its fuel pump.

Industry veterans also noted that the development of methane propulsion would not require any major new infrastructure or newly qualified personnel. (655)

Finally, liquid methane itself and its combustion products would be environmentally safer. (Like kerosene, the methane fuel would be mixed with cryogenic liquid oxygen, acting as an oxidizer in rocket engines.)

History of methane engine development

Given all the advantages of the methane fuel, KBKhA started considering switching existing and prospective rocket engines to methane. Among candidates were the RD-0110, RD-0120, RD-0124, RD-0234, RD-0242 and RD-0256. By 1996, the company concluded the study with a formal Technical Assignment for the development of an experimental methane engine. KBKhA also drafted a whole family of methane engines with a thrust ranging from 5 to 240 tons. Various designs were also evaluated. The company then started work on developing the rocket fuel out of the liquefied natural gas, which contains 98 percent of methane. This work was coordinated with Moscow-based Keldysh Center and TsNIIMash research institute -- both key planning and advanced research organizations of the Russian space agency, Roskosmos.

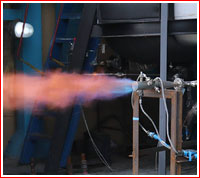

To perform live experiments with methane rocket fuel, KBKhA chose the veteran RD-0110 engine, which propels the third stage of the Soyuz rocket. In 1997, a team of engineers at KBKhA rebuilt an experimental propulsion unit previously used for tests with kerosene and liquid oxygen into a demo engine designated RD-0110MD (where MD stood for "methane demonstrator"). The engine was installed into the company's Test Bench No. 4, which was upgraded with methane storage enough for 20 seconds of burning. On April 30, 1998, an experimental engine fired for the first time burning liquid natural gas. Another live test took place on December 3 of the same year. (331)

KBKhA then converted to methane its prospective RD-0146M engine, which was originally designed to burn liquid hydrogen fuel.

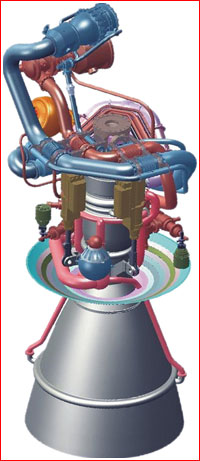

Between 2002 and 2005, KBKhA teamed up with European industry to develop a reusable methane engine with a thrust of 200 tons under the Volga project. Finally, in 2006, the company started work on a reusable engine designated RD-0162 for the Russian MRKS-1 reusable space booster. RD-0162 would have a thrust of 203.9 tons. Due to the complexity of the technology, in 2012, KBKhA decided to precede the full-size engine with a scaled demo named RD-0162SD with a thrust of 42.5 tons. In case the project was successful, the engine could propel a compact launch vehicle.

This work created a foundation for the development of new-generation engines burning liquid methane. Since then, several concepts proposed by Russia's key rocket developers relied on these engines. For example, RKTs Makeev, based in Miass, proposed the Riksha launcher, while the Volga branch of RKK Energia considered a methane-burning stage for the Vozdushny Start system. A methane engine was also proposed for the next-generation third stage of the European Vega launcher.

In 2011, GKNPTs Khrunichev, the developer of the Proton rocket, officially started the development of the MRKS-1 reusable rocket system relying on methane engines. (655)

Along with the Voronezh-based KBKhA, the KB Khimmash (a.k.a. KBKhM) design bureau in Korolev developed a methane version of the engine designated S5.86 No. 2 with a thrust of 7.5 tons. It was tested for the first time in 1997 at the NITs RKTs center north of Moscow. During a test on July 27, 2011, the engine fired for 2,000 seconds, proving the capability for multiple firings and confirming the absence of residue in fuel lines even under the most adverse conditions. In 2014, NPO Energomash in Moscow disclosed a design of the RD-192 engine also intended for methane fuel.

Methane engines for Soyuz-5

The Soyuz-5 design would rely on the yet-to-be developed RD-0162 or RD-0164 engine. According to early reports, the core stage, as well as optional add-on boosters would feature two such engines each. The upper stage could be equipped with an upgrade of the existing RD-0124 engine, modified to burn methane instead of kerosene. This version of the engine would be called RD-0124M. By 2015, the second stage was expected to feature the RD-0169 engine (INSIDER CONTENT).

According to further reports, (possibly describing a later incarnation of the Soyuz-5 design), the core stage and strap-on boosters would be equipped with a single RD-0164 engine each. The methane version of the RD-180 engine, known as RD-180MS was also considered. If successful, the methane-burning engines could later migrate to superheavy rockets and to reusable launchers.

In September 2016, Roskosmos awarded a 809-million-ruble ($12.66 million) contract to KBKhA, which would fund the development of the methane engine until the end of 2018. The contract called for the development and testing of a demo engine with a thrust of 7.5 tons, followed by tests of the experimental engine with a thrust of 40 tons. In turn, it would pave the way for the development of an engine prototype with a thrust of 85 tons.

Launch pads for Soyuz-5

From the outset of the project, engineers hoped to cut the time for the on-pad preparation from two days for old Soyuz rockets to just one day for Soyuz-5.

Soyuz-5 could use modified launch facilities of the Soyuz family. However a major departure of the Soyuz-5 design from the classic cone-shaped architecture of Soyuz rockets toward a more traditional cylindrical design will likely mean that the iconic "tulip" structures of the launch pad would have to go.

As of 2013, a pair of Soyuz pads operated in Baikonur, a total of four Soyuz launch pads once existed at Russia's northern launch site in Plesetsk, and one pad was operational at the European space center in Kourou, French Guiana. One more pad was under construction in Vostochny in the Russian Far East and completed in 2016.

Development of the experimental project

TsSKB Progress first disclosed the existence of the Soyuz-5 concept in March 2013. The head of the company Aleksandr Kirilin mentioned the work in the context of the cancellation of the Rus-M project in 2011, which became a victim of the competition with the Angara. According to Kirilin, the work on Soyuz-5 started at the company's own initiative, however it became a part of a broader study code-named Magistral ("Main Road") looking into the future goals in space conducted by the Russian space agency, Roskosmos. In June 2013, TsSKB Progress unveiled a scale model of Soyuz-5 at the Paris Air and Space Show in Le Bourget, France. On June 27, at a press-conference dedicated to the activities of TsSKB Progress in the first half of 2013, the company's head Aleksandr Kirilin said that given adequate funding, the rocket could be built during the time period from 2020 to 2025.

The development of the preliminary design (abbreviated in Russian as EP) for the Soyuz-5 rocket was formally started within TsSKB Progress on Dec. 10, 2013. The work was to be completed at the end of 2014 or beginning of 2015. On April 15, 2015, the project was reviewed by the scientific and technical council, NTS, of the Russian space agency.

Soyuz-5 survives budget cuts

By 2015, Roskosmos put the price tag of the Soyuz-5 program at 30.79 billion rubles, which would be spent from 2018 to 2025 within the Feniks (Phoenix) development effort.

A requested budget for the Soyuz-5 program (in millions, as of 2014):

| Currency | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russian rubles (millions) | 283.2 | 911.2 | 1,336.1 | 2,985.4 | 5,234 | 6,268.9 | 6,488.3 | 7,283.2 | 30,790.3 |

The agency hoped to issue a technical assignment for the vehicle during 2016 or 2017. Along with Roskosmos, the Russian Ministry of Defense apparently also showed some level of interest in a Soyuz-5-type vehicle. In 2015, the Russian government promised a federal tender for the Feniks project.

However at the end of 2015, the Soyuz-5 project tittered on the brink of cancellation, due to severe budget cuts in the draft of the Russian Federal Space Program, FKP-2025, which would allocate budgets from 2016 to 2025. Yet, living up to its new name, the Feniks project survived the latest budget slump even if in a streamlined shape. On December 30, 2015, Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin said that the Feniks project would produce a successor to the Soyuz family of rockets and will also serve as the first stage of the super-heavy booster. "The president worked hard to prompt Roskosmos' move in this direction and despite cost savings, a way was found to optimize the budget to begin this project," Rogozin said.

At the time, the Feniks concept was apparently still remained in a definition stage with solid rocket motors and even kerosene-fed RD-171 engines still on the table for a possible use in the future rocket.

Roskosmos pushes methane-propelled rocket

Head of Roskosmos Demitry Rogozin presents new economic specifications of the proposed methane-propelled launcher at the Ustinov Baltic University in September 2019.

By 2017, the Soyuz-5 and Feniks designations were given to a new-generation rocket, which was first formulated within the Sunkar concept. As a result, ongoing plans at RKTs Progress to develop a methane-based launch vehicle were initially renamed Soyuz-7. However by 2019, the Soyuz-7 designation was applied to a newly proposed launcher, which would use the RD-180 engine on the first stage, before it was re-designated Soyuz-6 in September 2019. In any case, the prospective rocket employing liquid methane was apparently left with an abbreviation RN SPG, which stands for the "launch vehicle with the liquefied natural gas" for the time being. The vehicle was later identified as Soyuz-SPG.

Speaking at Moscow State University, MGU, on May 23, 2019, Head of Roskosmos Dmitry Rogozin showcased the methane-propelled launcher among several prospective vehicles in the future Russian rocket fleet. According to Rogozin's presentation, the RN SPG vehicle would have a payload of nine tons to the low Earth orbit. The first stage of the rocket, carrying the methane engine, was promised to be reusable.

Rogozin then provided more technical and economic details about the methane-propelled booster during his visit to the Ustinov Baltic Technical University, BGTU Voenmekh, in September 2019. An official photo from Rogozin's presentation showed a slide comparing the specifications of the prospective RN SPG rocket with the operational Soyuz-2-1b vehicle. The following numbers could be discerned:

| Specification | Soyuz-2-1b | RN SPG |

|---|---|---|

| Payload to low Earth's orbit | 8.2 tons | 9.0 tons |

| Payload to geostationary transfer orbit | 2 tons | 2.2 tons |

| Payload fairing diameter | 3.7 - 4.1 meters | 5.2 - 7 meters |

| Flight reliability | 0.98 | 0.99 |

| Processing time on the launch pad | 2-5 days | Less than a day |

| Type of preparation on the launch pad | Manual | Automated |

| Number of components and assembly elements, DSE | ~4,500 | ~2,000 |

| Production complexity | ~220 thousand work hours | ~174 thousand work hours |

| Production cost | ~1,280 million rubles | ~900 million rubles |

| Price per launch | ~$45 million | ~40.5 million |

The slide, showing tandem (in-line) architecture of the launcher, indicated that the new rocket would be based at the Soyuz complex in Vostochny, and emphasized the simplification of the launch pad infrastructure in case of the transition from Soyuz-2 to the methane booster. According to the document, such key features of the launch facility as four side support structures, the service tower and underground (service) system would all be not needed.

In a July 13, 2020, interview, Head of Roskosmos Dmitry Rogozin claimed that the work on the methane-propelled rocket had continued without providing any details.

After Rogozin's visit to KB Khimavtomatiki, (KBKhA) in Voronezh (developer of the RD-0150 and RD-0146 engines) on July 14, 2020, Roskosmos said that he had directed the company to accelerate the work on the new generation engines burning hydrogen and methane with the goal of developing the Angara-5V rocket no later than 2025 and a new commercial methane-propelled vehicle to replace the Soyuz-2 series.

Chronology of the Soyuz-5 project:

2013 August: TsSKB Progress completes the Magistral-Soyuz-5 study, considering a new generation of mid-size launchers applicable for human-rated systems.

2013 Dec. 10: Order No. 1130 at TsSKB Progress initiates work on the experimental project (preliminary design) of the Soyuz-5 rocket.

2014 Feb. 6: Order No. 114 at TsSKB Progress issues addendum to the experimental project of the Soyuz-5 rocket.

2014 Dec. 31: The project completion date for the Soyuz-5 rocket.

2015 April 15: The Scientific and Technical Council, NTS, at Roskosmos reviews the experimental project of the Soyuz-5 project.

Specifications of the Soyuz-5 rocket presented at Paris Air and Space Show in Le Bourget in June 2013:

| Liftoff mass | approximately 575 tons |

|---|---|

| Maximum length | 46.5 meters |

| Fairing diameter | 4.35 meters |

| Payload to a low Earth orbit with an altitude of 200 kilometers and an inclination of 51.7 degrees toward the Equator | 16.5 tons |

| Oxidizer | Liquid oxygen |

| Fuel | Liquefied natural gas |

| Number of stages | 2 |

| Optional upper stage to reach medium-altitude, high-perigee elliptical and geostationary transfer orbits | Fregat |

Evolution of the Soyuz-5.1 specifications:

| - | 2013 | 2014-2015 |

|---|---|---|

| Liftoff mass | 268.7 tons | 268.7 tons |

| Payload to a 200-kilometer orbit with an inclination 51.7 degrees (Vostochny) | 9.2 tons | 9.0 tons |

| Payload to a 200-kilometer orbit with an inclination 98 degrees (Plesetsk) | 7.45 tons | - |

| Payload to a 200-kilometer orbit with an inclination 98 degrees (Vostochny) | 7.56 tons | ? |

| Payload to a geostationary orbit | 1.0 tons | ? |

| Oxidizer | Liquid oxygen | Liquid oxygen |

| Fuel | Liquefied natural gas | Liquefied natural gas |

| STAGE I | - | -- |

| Structure mass | 14,000 kilograms | 14,000 kilograms |

| Propellant mass | 184,000 kilograms | 184,000 kilograms |

| Propulsion system thrust at sea level at 106 percent | 340.0 tons | 339.3 tons |

| Propulsion system thrust in vacuum at 106 percent | 390.7 tons | 381.4 tons |

| Specific impulse at sea level | 311.5 seconds | 317.6 seconds |

| Specific impulse in vacuum | 358.0 seconds | 357.0 seconds |

| STAGE II | - | - |

| Structure mass | 4,300 kilograms | 4,300 kilograms |

| Propellant mass | 50,000 kilograms | 50,000 kilograms |

| Propulsion system thrust in vacuum | 73 tons | 73 tons |

| Specific impulse | 372 seconds | 372 seconds |

Known specifications of the RD-0164 engine:

| Thrust at sea level | 280 tons* |

|---|---|

| Thrust in vacuum | 300 tons |

*In early 2021, industry sources quoted a thrust of 340 tons at sea level

Known specifications of Russian methane-burning engines (RD-0162 series):

| - | RD-0162 | RD-0162SD |

|---|---|---|

| Thrust at sea level | 203.9 tons | 42.5 tons |

| Specific impulse at sea level | 321 seconds | 300.5 seconds |

| Specific impulse in vacuum | 356 seconds | 347 seconds |

| Combustion chamber pressure | 160 kilograms per square centimeter | 150 kilograms per square centimeter |

| Number of burns (flights) | 25 | 25 |

| Thrust levels | 133 percent | 133 percent |

| Burn time during the flight | 200 seconds | 200 seconds |

| Oxidizer | Liquid oxygen | Liquid oxygen |

| Fuel | Liquid natural gas | Liquid natural gas |

| Engine mass | 2,100 kilograms | 500 kilograms |

| Engine length | 3,550 millimeters | 2,000 millimeters |

| Engine diameter | 1,650 millimeters | 930 millimeters |

| Development start | 2006 | 2012 |

Next chapter: Amur-SPG project (INSIDER CONTENT)

Story and illustrations by Anatoly Zak; Last update:November 10, 2025

Page editor: Alain Chabot; Last edit: January 9, 2016

All rights reserved

A June 2013 version of the Soyuz-5 rocket unveiled at Paris Air and Space Show in Le Bourget.

A live test of RD-0110MD engine burning liquid methane. Credit: KBKhA

The RD-0162 engine. Credit: KBKhA

Soyuz-5 could pave the way to a a series of heavy and super-heavy rockets burning methane fuel, including a launch vehicle capable of sending a new-generation manned spacecraft to the vicinity of the Moon. Copyright © 2013 Anatoly Zak

The Soyuz-5 family as of 2014. Left to right: Soyuz-5.3, Soyuz-5.2, Soyuz-5.1. Credit: RKTs Progress

On Nov. 10, 2025, Roskosmos announced test firing of an igniter for a methane engine identified as RD-0177M. (INSIDER CONTENT).