Style of Management and Leadership (original) (raw)

Contents

Summary

Style of Management

Seeing things as they are

Organisation

Authoritarian organisation

Participative organisation

Degree of participation

Style of Management in Different Countries

Different countries

The changing pattern

Effect on standard of living

Impact of the Style of Management on Organisations

Style of management in organisations

Overcoming problems of size

Training

Appendix

Authoritarian attitudes result in confrontation,

leadership and co-operation result in economic success

Notes <..> and References {..}

Illustrations (Click any illustration to see the full-size chart)

1-5 Knocking One's Head Against a Brick Wall

6 Style of Management in Individual Countries

7 Style of Management in Different Countries: Changes over Ten Years

8 Effect of Style of Management on GNP/head in Different Countries

9 Effect of Style of Management on Rate of Increase of GNP/head

10 Style of Management in Large, Medium and Small Enterprises

11 Improving the Effectiveness of Management

Relevant Current and Associated Works

Relevant Subject Index Pages and Site Overview

SUMMARY

What Manfred Davidmann has done in his work on the general management of enterprises and communities is to lay the foundation for, and develop, what truly can be called 'management science'.

A management science which is objective, sees things as they are. Manfred Davidmann vividly asks us 'to see things as they are' and shows us how to do this. What he puts before us in his writings enables us to move into whatever direction we wish to take. But, as he used to say in his lectures, 'at least we will be fully aware of the consequences of what we are doing'.

This report is a landmark in management and community science and their methods. It pulls the diverse world-wide events in industrial relations and in government/people confrontation into a meaningful, clear and highly significant picture of interrelated events fitting into a consistent pattern.

Clearly defined and described is the whole scale of style of management and organising, from fully authoritarian to fully participative. It applies to community organisations, commercial enterprises, political parties, whole countries. The social assumptions underlying each of the styles are given, as are problems they create, the symptoms by which they can be recognised, and the ways people work together or against each other within them.

There are clear definitions of authority and of responsibility, and how they are applied in companies under different styles of management. Also discussed are the extent to which authority is balanced between top and bottom, participation in decision- making and the corresponding style of management.

Style of management is shown to depend on the size of the enterprise and related to company effectiveness and results.

The different problems faced by small and large companies are outlined as well as how to overcome problems of size, how to improve the effectiveness of management, and the need for teamwork.

Smaller companies are more effective than larger ones, and the effectiveness of larger companies can be increased by about 25 percent by training. An illustration shows how style of management was improved by appropriate management training in a large organisation.

The right to strike is a basic component of any style of management and Manfred Davidmann defines it, giving its source and authority. He looks at the extent to which people are allowed to strike, and at the extent to which they are able to strike, and what this indicates.

Of interest is his description of Britain's labour relations struggle in the seventies. This brings in the right to strike, unofficial strikes, role of shop stewards, economic damage resulting from introducing such labour relations legislation and the extent to which this was known in advance.

Manfred Davidmann defines and develops a scale of style of management, shows how to place organisations on this and how to chart their progress in time. It is illustrated by changes occurring in eleven countries over ten years. This report was written about fifteen years ago and the examples are drawn from that period. However, they illustrate how to place organisation on the scale and how to evaluate changes in the style of management.

STYLE OF MANAGEMENT

Here we are looking at and discussing some of the basic requirements for achieving good management and administration, good leadership and government.

From the point of view of results, the effectiveness of the organisation is determined by the way work is organised and by the way people work with or against each other. The way in which people co-operate with each other, with the leadership and with the community, indeed the extent of their commitment to their organisation, depend on the style of management.

So here we look at different styles of management, on their impact on people, on the way in which people work together and on results.

Just think of the many supplies and services required daily to enable a large city like London to survive. Food has to be produced, harvested, stored and transported. Waste products have to be collected and treated or dispersed. Electricity has to be generated and distributed, transport has to be provided. Houses have to be built. Streets have to be cleaned and maintained, the district has to be policed. And all these and much more for millions of people, daily.

In our modern, industrialised, technological and highly competitive international environment it is essential that many experts from different areas of activity and different levels of society coming from different backgrounds work together to successfully achieve the completion of large projects such as exploring space, or the building of large oil gathering and refining installations.

Many experts have to work together to provide our daily needs, to enable us to have good and satisfying lives. Discord in one area can inconvenience many people and it is essential that people co-operate with each other freely and effectively.

Experience shows that the larger the organisation the more difficult it is to achieve the necessary degree of co-operation and that larger organisations are usually much less effective than smaller ones as people are working against each other instead of co-operating. We will see that improving the style of management can by itself increase the effectiveness of operating, improve results obtained and the way in which resources are being used, by about 20-30%. The gains to be made by improving the style of management are thus very considerable not only from the point of view of a better return to the shareholders and to the community but also from the point of view of greater contentment and satisfaction felt by employees.

Consider the following two stories. The first is about a civil servant:

When a very senior civil servant retired to his country cottage, he caused a stir in the village. Every morning one of the local boys would call and disappear for a minute or so into his cottage. They persuaded the boy to reveal what was going on: "I am paid to knock on his bedroom door and shout a few words and then he shouts a few words". He finally told them what these words were. He said: "I shouts 'The Secretary of State wishes to see you', and he shouts back 'To hell with the Secretary of State'."

The second story is about a man who is working as a foreman in the garage of a Municipal Forestry Commission.

The garage wasn't efficient but since he started working for them things run much more smoothly. If a spare part is needed but cannot be obtained, if anything goes wrong, he is the one who sorts things out in his own quiet and effective way. For example, when the garage was told that it would take some six months for a new radiator to be delivered to them, he simply telephoned the factory to confirm this disturbing news. The radiator was delivered beautifully wrapped the next day by special messenger.

You probably know the name of this foreman. It is Alexander Dubcek, the man who led his country in a bid for freedom in l968. This is what he was doing a few years ago.

What he gets from those with whom he comes into contact is not just esteem and respect but also co-operation and as a result 'things run much more smoothly'. Compare this with the attitude to his work of the retired civil servant whose idea of blissful retirement is to be able to shout every morning 'To hell with the boss'. This kind of frustration with management and workplace indicates internal conflict and struggle, indicates considerable lack of identification with the organisation and its objectives.

People live and work together. Important is that the way in which they feel about their place of work, and the way in which they co-operate, depends on controllable factors, depends on the style of management.

Those who live with you, work with you, or work for you will think about living and working with you in either one way or the other. Certain is that the way in which they react depends on the way in which you behave, depends on your style of management, depends on the factors which we will now explore.

SEEING THINGS AS THEY ARE

|

|---|

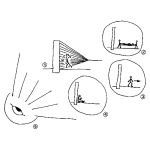

| Figures 1 - 5Knocking One's Head Against a Brick Wall |

All of us have at some time come up against a brick wall. We are trying to achieve something which is difficult and keep on knocking our head against this brick wall which stops us. It may be the system or the organisation or some other reason which is stopping us.

So we find ourselves in the position of knocking our head against a brick wall and Figure 1 illustrates this.

In that kind of situation, what can one do? The wall is very solid, very high, extends almost indefinitely on either side and its foundations are deep and strong. In other words we cannot get through it, we cannot climb over it, we cannot walk around it and we cannot tunnel underneath it. So what are the alternatives, what can we do?

Of course we can keep on knocking our head against the brick wall. Continuing to do so could have drastic results (see Figure 2). One lands up with a sore head and it may take some time to recover from this. The expression 'sore head' here covers a wide range from a general feeling of being fed up or of frustration to more severe symptoms.

Another way of dealing with the situation is to leave it, to emigrate, to find another job (Figure 3). People do not really like doing this and a lot of frustration can build up and be endured before people finally take the step. Their frustration has been building up for a considerable time before they take the step. It may have taken a year or two years before an employee makes up his mind to change his job and leaves.

There is yet a third way out of the situation (see Figure 4). One can sit down with one's back against the wall drinking tea, saki or whatever the local drink may be, letting the wall support one, taking it easy and playing the game according to the local rules.

These are really the only three ways out which are normally open to one. However, people who are involved in such a situation do not see it in such simple terms. People are often deeply emotionally involved in their work and home situations. Success or failure at work is important as it determines not only one's standard of living and the standard of living of those who depend on one but also determines the sense of well-being and satisfaction of the individual concerned. Hence people react strongly and emotionally to the kind of factors we are talking about and will be discussing.

What I am asking you to do now is something quite different and much more difficult. I am asking you to tear yourself out of this involvement with your situation at home or at work, with the kind of brick walls you are struggling with or which support you. I am asking you to see things as they are.

Figure 5 illustrates this. It shows the human eye looking at the total situation, seeing the situation as it is. We see the brick wall, the bricks from which it has been built, and their size. We see the thickness of the wall and the cement which holds it together. We see its height and its length and have a good look at the foundations. We see the individual, see what he is doing, see the alternatives open to him and the consequences which result from choosing any one of the alternative ways of behaving. Seeing the total picture we can then act accordingly, knowing the consequences of our actions. We can decide to move in any direction or take appropriate action about the wall itself but at least we will be fully aware of the consequences of what we are doing. We will then objectively see and assess the factors which enable people to co-operate with each other and to work together effectively.

ORGANISATION

We have seen that we need to leave preconceived ideas behind so as to see the situation as it is and that we need to see the complete picture.

The whole pattern of different ways of organising may be described as a sequence from one extreme to the other, as a kind of scale. At one end of the scale is the completely authoritarian organisation, at the other end the fully participative organisation. Having looked at the two extreme types of organisation, we will then be able to recognise and assess the style of management in organisations which combine aspects of both. Most governments, companies and organisations fall somewhere along the scale and these we will discuss later.

Hence so as to understand the scale and the characteristics and symptoms by which different styles of management can be recognised, and so as to describe the advantages and disadvantages of each, we consider firstly an organisation which is at one extreme end of the scale, namely a completely authoritarian organisation and then consider an organisation which is at the other end of the scale, namely a completely participative organisation.

A person's authority is the right to command and the power to exact obedience. Hence when considering authority {1, 2} one wants to know where the right comes from and how the power is used. It is this which points to the basic difference between authoritarian and participative organisations.

When I give a person work to do, I hold him accountable for the way in which he does it, that is he is responsible to me. This is the meaning of 'responsibility'.

AUTHORITARIAN ORGANISATION

Kings ruled by 'divine' right and they enforced obedience through, in the end, the death penalty. Under private ownership, authority is derived from ownership of the means of production and the penalty for disobedience is dismissal. In each case authority is centred at the top. It is the owners who delegate authority to the chief executive, and it is immaterial whether the owners are shareholders as in some countries, or the state in countries such as Russia.

In authoritarian organisations it is orders which are passed down from above and the manager's role is to pass orders down the 'chain of command'. He is usually not expected to make decisions and so carries little responsibility. He does order and may compel the worker to carry out the tasks demanded from him, to produce.

Those who run society on such lines find that the working population does not willingly work for the benefit of only its rulers and then they attempt to compel the working population to work. The stick is unemployment and the compelling force is the fear of the economic consequences of unemployment, is the threat of need.

They will then do all they can to make the stick more effective. The higher the level of unemployment and the greater the need of the working population, the greater is the fear of dismissal and the more effective is the stick. Hence it is those who believe in an authoritarian kind of organisation who advocate that the level of unemployment should be kept above a certain minimum level or that it should be increased, and who want to reduce social security spending.

To them it appears as if people do not want to work, as if conditions have to be created which force the working population to do as told, by depressing their standard of living <1> and the quality of their lives so that they become more dependent on the employer.

Examples of this attitude towards unemployment are the following newspaper headlines:

(a) Big fall in unemployment and record spending threaten economic trouble.

(b) Sharp fall in jobless a sign of overheating.

Authoritarian organisations are effective in an emergency and perhaps the best known authoritarian organisations are the armed forces.

However, enterprises organised on authoritarian lines have many problems. Orders are passed down and mistakes readily result in critical appraisal and dismissal. Hence people avoid making decisions so that matters to be decided are either passed up for the decisions to be made at a higher level, or decisions are made by committees as it is more difficult to dismiss all the members of a committee for jointly making a wrong decision. There are likely to be many such committees. People survive by becoming expert at passing the buck. Empire building takes place, this being one way of increasing job security. Blame is passed to someone else, empires are built at someone else's expense; people work against each other and we see conflict instead of co-operation. Senior management tends to be overworked, staff turnover tends to be high and workers restrict effort.

The kind of difficulties which arise are perhaps best illustrated by some examples:

- On one of the scheduled flights from Moscow {3} to the Soviet Far East only half the seats had been taken up so Aeroflot cancelled the flight and told the passengers to wait.

They waited in the packed terminal all that night and indeed all the next day when they were told that their flight would now be leaving.

Trying to join their flight they found that they had to pay an extra 25% of their fare as a fine for missing the first flight. - Nigeria ordered 20 million tons of cement {4} worth £650 million to be delivered during 1975. By the middle of October there were already 250 ships queuing to discharge their cement cargoes. A further 100 cement-laden ships were due the following week. Some of these would have to wait for more than two years to dock.

Only 4 million tons of the 20 million tons ordered had been delivered and in addition there were 150 general cargo ships queuing to discharge their cargoes.

By the end of December, 2,500 Greek seamen aboard 150 freighters had been "trapped" for more than seven months while waiting for permission to dock and unload. All seamen who had been stuck for more than four months were being flown home for Christmas by their employers.

The Nigerian government then announced a draft decree enabling them to charge owners £7,000 for every day an unauthorised vessel spent in Nigerian waters.

Normally the docks could handle less than one and a half million tons of cement per year and a basic cause of the congestion would appear to be lack of co-operation, contact and teamwork between different ministries and departments. - Gerald Smith when leader of the American delegation {5} to the SALT negotiations in Vienna which aimed to limit nuclear weapons, submitted remarkable Russian tables and drawings which compared the number and size of American and Russian inter-continental rockets and shelters for housing them. He was apparently submitting information prepared by Russian military intelligence themselves.

In a counter-statement the leader of the Soviet delegation, Vladimir Seminiov, made a new evaluation but was openly corrected by his military deputy, Colonel General Ogarkov.

After this meeting, Ogarkov took one of the American delegates to the side and whispered to him. He said there was no occasion whatsoever for the Americans to divulge their knowledge of Soviet military data in front of civilians of the Soviet delegation as these matters are exclusively the concern of Soviet military officials.

A fine picture of conflict instead of co-operation between Russian military and civilian officials, that is departments. - Israel earns much foreign currency from tourist traffic, but it was reported that the Ministry of Tourism continued to receive complaints from Israelis and foreign tourists regarding the inadequacy of sanitary conditions and other facilities at Ben-Gurion airport.

The Ministry spokesman also pointed out {6} that the airport was under the exclusive jurisdiction of the Ministry of Transport, to which all complaints should be referred.

A clear case of passing the buck which appears to disregard the interests of those using the airport. Just what is the job of a Ministry of Tourism?

These are only a few examples of the kind of wasteful way in which large units run on authoritarian lines muddle on through crisis after crisis. They cease to be able to learn from past mistakes, the same mistakes are made again and again. The reason some of them are still in existence is because their competitors are just as ineffective, are just as incapable of moving forward in any real sense.

Crisis succeeds crisis in badly managed as well as in authoritarian organisations. This may be due to bad management but in an extremely authoritarian organisation crises are often almost artificially created by managers so as to obtain co-operation. If I go to Jim and say "I want you to sweep the floor of this office three times within the next half-hour, or else!" he is not going to like this one little bit. He will go through the motions but the office will be badly swept and the next half-hour will appear to him to be an eternity of drudgery, boredom and frustration. If on the other hand I can say "We are in real trouble, some very nasty stuff has been spilled and it is important for all who work here that the floor be swept thoroughly three times and quickly, say within thirty minutes anyway. I wonder if we've got someone who could do it?", then he is likely to volunteer for the job. It will be done extremely well, it will get done within the half-hour and probably with five or ten minutes to spare. If afterwards I can go to him and say "Well done, we are all grateful" he will be left with the feeling of having spent half an hour most usefully serving the community, having done a very worthwhile job indeed. In other words, people try to help each other and in an authoritarian organisation crisis may succeed crisis as this is one way of getting work done. However, one can cry wolf once too often and in an authoritarian organisation 'This must be done today' is succeeded by 'Do this now' which is succeeded by "We are in a mess, drop all else and do this now". In such circumstances people soon learn that crises are the routine rather than the exception and cease to care.

Centralised decision making is quick and decisions can be implemented quickly but it generally fails to utilise the potential of the employees.

Larger organisations also generally fail to perform as well as they should because of internal conflict, because of confrontation, lack of co-operation and lack of teamwork.

Having now looked in some detail at the kind of organisation we find at one end of the scale, namely the authoritarian organisation, we can now look at the other end of the scale, at a completely participative organisation. Following this we will look at the large number of organisations which are somewhere in between.

PARTICIPATIVE ORGANISATION

The story is told that when a new manager was appointed {1} to a textile mill in America he walked into a weave room the day he arrived, walked directly over to the agent (for the Textile Workers Union of America) and said "I am the new manager here. When I manage a mill, I run it. Do you understand?". The agent nodded and then waved his hand. The workers, intently watching this gesture, shut down every loom in the room immediately. The agent turned to the manager and said, "All right, go ahead and run it."

This story with great clarity makes the point that there is another authority besides the manager's. The workers' representative has authority and exercised it. The question arises, where does his right to command come from and how did he use his power to exact obedience?

The shop steward is elected so that his authority stems from those who elected him and who work in factory and office. The source of his authority is the consent of the managed to be managed. The method of power is the withdrawal of that consent which is in effect the withdrawal of one's labour, for example by going on strike.

Employees participate when they agree to allow themselves to be organised by an employer, and organisation which is based on consent of those being organised is participative. In a participative organisation people accept responsibility for work to be done, accept that it is their job to carry out a part of the company's activities and that they will be held accountable for the quality of their work. The manager's job is to back his subordinate by removing obstacles from the subordinate's path, the subordinate asking for such assistance as the need arises. The manager co-ordinates the work of the group which he manages with that of the higher group in which he is a subordinate. As work may be a source of satisfaction or of frustration, dependent on controllable conditions, the extent to which subordinates derive satisfaction from their work also depends on their own manager's and on the organisation's general style of management. People who derive satisfaction from their work will like doing it and do it to the best of their ability; if work is a source of frustration, they will restrict effort and the work is likely to be done badly.

An organisation built on this basis is participative, and this means that participation through decision making, including setting of targets, takes place at all levels of the organisation.

DEGREE OF PARTICIPATION

Large employers are often paternalistic, and employees company oriented, sometimes staying with their employer throughout their working life. Since their employees are economically tied to the company, dependent on it for services such as housing, medical or educational, this does not mean that these companies use a participative style of management. In Japan and similar countries the compelling force is the fear of 'losing face'. In Russia and in China the workers are not allowed to strike in any real sense and thus have no authority and orders are passed down from the top. Protest is forbidden and to demonstrate takes a highly developed sense of social responsibility and very considerable courage. It is seen that the Russian and Chinese systems of government and organisation are authoritarian systems in which their people work as directed.

We have described here in outline two systems of organisation which can be regarded as forming either end of a scale. The position of any organisation on this scale depends in each case on the balance between the two kinds of authority, that is depends on the degree of participation in decision making which is practised. One can place on this scale any system of running a company or of governing a country, by considering for example whether and to what extent decisions are being made at the various levels or whether people merely follow orders, or whether and to what extent people are free to withdraw their labour, are free to strike, to what extent authority is centred at the top, or where the balance of power lies between management and worker. The position where an organisation is placed thus depends on the balance of authority between ruler and ruled, between owner and worker, between the establishment and the population.

We can now develop this scale and place a number of organisations on it over the complete range from one end to the other.

If we were to do this for individual companies then this would require a detailed knowledge in each case of the style of management and of company effectiveness. So what we will now do in the next section is to look at the more generally known balance of authority in different countries and place them on our scale.

STYLE OF MANAGEMENT IN DIFFERENT COUNTRIES

We are now looking at the way different countries are managed, doing so country by country.

The style of management of government in different countries can also be anywhere on the scale, from fully authoritarian (dictatorship) at one end of the scale to fully participative (policy decided by the people) at the other end.

This is a fundamental scale which cuts across artificial and ineffective political divides - dictatorship of the left is dictatorship just like that of the right. Dictatorship is dictatorship no matter whether the organisation or political party is on the left or on the right of the political spectrum. Under participative government and democracy the government and leadership put into effect the wishes of the people, the policy decided by delegates directly appointed by and directly responsible and accountable to the people. Under authoritarian government or dictatorship the government and its 'experts' tell the people what the government or rulers decide the people have to follow.

Here 'directly' means selected by the people and voted for, each person having one vote. This is very different from delegates being selected by or being accountable through an establishment such as a political party's or a Board of Directors.

Real struggle is not between political left and right but is a struggle for democracy against dictatorship (authoritarian style of management) in all community organisations and at all levels.

Authoritarian attitudes result in confrontation, leadership and co-operation result in economic success.

The way in which countries are managed, that is their style of management, of course varies from country to country and changes as time passes. Figure 6 illustrates the style of management.

The left hand side of the horizontal scale corresponds to the fully authoritarian, while the right hand end corresponds to the fully participative way of managing. The two ends are called 'A' and 'B' respectively, for convenience.

What we can now do is to place on the scale some lines corresponding to the style of management adopted in different countries and then to discuss the pattern, following this by a discussion of the effectiveness of different styles of management.

In doing so we need to remember that we are not in any way concerned with opinions and feelings and beliefs about whether one country is better than another, whether one method of organisation is better than another, whether one political system is an improvement on another. We are concerned here only with the situation as it is, we are concerned only with objective facts. Hence we assess the style of management by two factors only, namely on the one hand by the extent to which authority is centred at the top and on the other hand by the extent to which authority is centred at the bottom.

Our measure for the extent to which authority is centred on the bottom is the extent to which working people may withdraw their labour, that is the extent to which they are permitted to do so by the laws of the land and the extent to which they are actually able to withdraw their labour.

We assess the style of management by these factors only and while at the authoritarian end of the scale there is generally little doubt about the extent to which authority is centred at the top, this factor is more difficult to assess in democratic societies and here we find that the extent to which people are permitted to withdraw their labour and the extent to which they are doing so is a clearer and more definite way of assessing a country's style of management on the scale.

In the democratic countries are found a wide range of companies and organisations ranging from highly if not completely authoritarian to the almost completely participative, ranging from the armed forces at one end to worker-owned and controlled enterprises on the other. However, this does not in any way invalidate the scale or its general validity, nor does it detract from the usefulness of the comparison. On the contrary, the existence of such widely differing systems makes it even more important that we become aware of the impact of different styles of management on people and on results.

Hence we now discuss the style of management in individual countries, country by country.

DIFFERENT COUNTRIES

Russia

Authority is clearly centred at the top and strikes are illegal. This places Russia straight on the line marked 'A' (see Figure 6a). The right to strike is not recognised in the Soviet Union.

It appears {7} that co-operation with management is enforced and that the 'collective contract' between the administration and the workers does not necessarily offer real job security. Rewards include prizes such as public commendation, certificates of merit, bonuses or gifts of value. Slack workers may be reprimanded, demoted to lower paid work for a period of up to three months, or sacked. There was a deep reluctance for workers to take responsibility for any initiatives.

In the Spring of l976 there were some reports of strikes and riots in Rostov-on-Don and in Kiev. In Riga it seems that the loading and unloading of cargo had been seriously delayed by dockers. These were caused by {8} widespread discontent over food shortages.

It seems that fairly recently a group of thirty-eight Soviet workers signed a petition against repression and oppression in the field of work. They apparently brought the document to the attention of the Soviet authorities. However, Trade Unions in Russia appear to serve the employer (state) rather than the workforce and the attempt to set up a free (unofficial) trade union for representation of the actual workforce has been countered by repression.

Spain

Not so long ago the authority in Spain was clearly centred at the top and strikes were illegal but the workers did strike and bitter confrontations and struggle developed between workers and employers. This placed Spain pretty close to the completely authoritarian end of the scale where authority is centred at the top and strikes are illegal. The fact of protest and confrontation means that it was then located just that little bit further towards the participative end of the scale (see Figure 6b).

Recently Spain moved much further from dictatorship towards democracy and this change is shown on the scale by a movement towards greater participation, shown by a move from position 1 to position 2.

The considerable social upheaval and internal terrorist activities (by which I mean the use of vicious and brutal treatment of civilian population for the sake of 'political' ends) may be related to the country's form of government or to the desire for self-government in certain parts of the country but they do not seem to be related to the right to strike.

Poland

When in l970 the Polish government increased food prices very appreciably thus reducing the standard of living of the working population there were spontaneous strikes in some areas. There was confrontation and rioting, and some workers lost their lives. The Polish government was forced to cancel the price increases and the disturbances resulted in a change of government, resulted in change towards greater co-operation with the working population. Mr. Gomulka was replaced as party leader by Mr. Edward Gierek.

So here we have a style of management which before l970 was completely authoritarian, with authority centred at the top, with strikes being illegal. Not only did they strike but they forced a change of government, the new government being more concerned about the standard of living of the working population. This move is illustrated by Figure 6c, by the move from position l to position 2. Poland's position 2 is more participative than Spain's position 1, since the Polish workers' action resulted in a fundamental change of policy on the part of the government.

In June l976 the Polish factory workers again forced the Polish government to cancel drastic food price rises the day before they were due to come into force {9}. The Prime Minister went on Warsaw television in the evening to announce his government's change of mind. He said that as some workers were critical he had instructed the Polish parliament not to proceed with the bill providing for the price increases. This is the second major victory for Polish workers in communist Poland. It being the second time that Polish workers forced their authoritarian government to change its mind would seem to place Poland still further into the region of participative management and this is shown on the scale by the move from position 2 to position 3.

USA

The United States is a democratic country and it is more difficult to determine to what extent authority is centred at the top and to what extent it is balanced by the authority of the working population exercising their power through the withdrawal of their labour. The Taft-Hartly Act limits the right to strike, seemingly shifting responsibility for declaring a strike from the factory floor to the union head office. A cooling-off period may be ordered which delays the beginning of a strike by some months, in this way giving management and workers another chance to negotiate an agreement before engaging in open confrontation, giving both sides another chance to avoid large scale national economic damage which could otherwise arise.

The relative position of one country with respect to another on the scale seems fairly clear. The right to strike exists and is openly used but the right to strike is limited. Ownership is in private hands rather than in the hands of the state as in Russia and so we place the USA a good bit further towards the participative style of management, roughly just over half of the way along the scale towards participative management, and this is illustrated by Figure 6d.

Australia

On the whole, Australia is not far away from the United States as regards the right to strike. However, in Australia strikes are illegal since arbitration is compulsory. This places Australia close to the USA but also closer to the authoritarian style of management and this is shown by Figure 6d.

United Kingdom (UK)

The Industrial Relations Act came into effect in 1971. This made 'unofficial' strikes illegal and in this way transferred the responsibility for deciding whether to strike or not from the men on the spot, that is from their elected shop steward, to the union head office official. Agreements between management and unions became enforceable at law which meant damages could be claimed, it being possible to prosecute unofficial strike leaders.

Before the Act there was no legal limitation to the right to strike but ownership was private so that the UK occupied roughly position 1 on the scale (see Figure 6e).

I am told that the Industrial Relations Act was somewhat tougher than the corresponding Taft-Hartley Act but not as severe as Australia's compulsory arbitration. Hence with the passing of the Industrial Relations Act, the United Kingdom moved from position 1 to position 2.

What happened then was predictable and devastating.

A good deal of pressure had been used to have the Act passed. Unemployment seemingly had been allowed to rise from about 300,000 to about the 1 million mark and there had been much reporting of strikes which stressed that there were many strikes and that many of them were 'unofficial' or 'wildcat' strikes. The name 'wildcat' is but another name for an unofficial strike. Clearly there were many strikes and we seemed to have relatively more strikes than countries such as Australia and America.

But when the Act came into force there began a bitter struggle between the working population and those who run the country, a hard and tough struggle which year by year increased in severity and in extent. It was in some ways a most remarkable conflict, its major confrontations taking place in winter after winter in increasing order of severity. Winter is the sensitive time for Britain, heating is necessary for comfort and there was countrywide confrontation with each winter more and more industries and services becoming involved on a nation-wide scale. The Post Office was affected, followed by the supply of gas, electricity, the docks and coal.

The government, deeply involved in this confrontation, was finding loopholes to prevent strike leaders from either winning their cases in the courts or else from becoming popular heroes. It still continued to battle with the miners three months after oil prices had been vastly increased and threatened the economic independence of the country.

Such a fierce, fundamental and protracted confrontation involving directly and indirectly the well-being and comfort of probably the whole population of the country would not have taken place about a matter such as whether an agreement was binding on the parties, was legally enforceable. What then was the point at issue between them?

Management and worker representatives in the United Kingdom are trained to negotiate, form agreements and stick to them. Bargaining may be hard and prolonged but in the end you can only work with people you can trust and that means with people whose word means something. Agreements reached at the end of the bargaining process were on the whole being implemented and maintained unless there was good reason to do otherwise.

There are a few, some small percentage, who believe in conflict and confrontation for its own sake. They see it as an end in itself. It is they who may break their word and who could fail to maintain the bargains they have struck. Restraining them by law would not have caused this kind of battle and confrontation.

Clearly a very fundamental and most important basic right and freedom was at stake.

In addition, the effect the Industrial Relations Act would have was known in advance. The introduction of similar legislation in the United States and Australia had, of course, drastically reduced the number of strikes. Unofficial strikes were out, strikes recognised and set by union headquarters were in. A large number of relatively small strikes, in individual factories all across the country, had been replaced by nation-wide confrontation, by whole industries being shut down at the same time. In the United States it isn't just one little or even one large dock or harbour which is immobilised due to strike, it is just about the whole seaboard which is shut down. Replacing the large number of small strikes by the few countrywide ones increased the economic damage done enormously, multiplying it by about four.

This is what happened in the United Kingdom. The number of strikes were reduced drastically but the economic damage caused by the fewer but countrywide strikes was multiplied by a factor of four or even more. In the end much of Britain's industry was working a three-day week.

Those who managed the country were prepared to face this kind of heavy loss, this kind of damage to the economy of the country and to its well-being. From their point of view also, what was at stake was a basic shift in the balance between the authority and power of those who work as compared with the authority and power of those who run the country.

The slave has to work whether he likes it or not, the free man may withdraw his labour. What was at stake was a most essential right and freedom, the right of every ordinary worker to withdraw his labour, to go on strike.

The enterprise may be located anywhere in the country, away from the capital. Union head office or the local officials are too busy doing whatever they are doing to sort out the local grievances. In the end the men put pressure on their shop steward and strike. This is an 'unofficial' strike, which means that it has not been recognised by the head office of the union. It is a relatively small strike affecting only a few people in the locality. The strike may then receive publicity in the national newspapers and a union negotiator or official dashes to the scene, sorts out the grievances, negotiates an agreed settlement or at least gets negotiations going. The strike is over. The men have succeeded in bringing their grievances to the notice of both union and management and negotiations are proceeding.

An unofficial strike is not just a way of getting management to the negotiating table, of impressing management with the strength of feeling about a particular grievance. It is also a way of getting the union establishment to act for the membership. The union establishment, far removed from the membership, is far too often too busy pronouncing about politics, economics, the state of the country and the world, wining and dining with members of the establishment on the other side and so 'sorting out' abstract vague general matters which could not be further removed from the problems of the workplace.

The shop steward is elected by the workforce, he represents the working people in their place of work, he talks for them to the management, he negotiates for them, it is he who is backed by the union in the work that he is doing. And generally, although there are a few exceptions, he exercises a restraining influence and it is pressure from the working people which pushes him into open confrontation, into leading them in strike.

This then is the central, relevant and utterly important issue at the root of the confrontation. The Industrial Relations Act and any similar legislation takes away the right to strike from the working population and gives it to the union establishment, takes away from them the ability to decide their own course of action, to agree voluntarily to work for the employer or to decide when to withdraw their labour, takes away from the working population the ability to make their voice heard, the power to express their opinion, the power to influence events, to negotiate in their own interest.

The Industrial Relations Act took away power from the ordinary working people and gave it to a few people at the top of the union establishment. It replaced upward flowing authority (from the people) by downward flowing authority (from the top). It removed and destroyed a basic freedom by taking the power to withdraw their labour away from the workforce. It did not just limit the right to strike, it took it away from the workforce and together with the corresponding authority and power gave it to the few people at the top, to the establishment.

The result of the ensuing confrontation and struggle was that the Industrial Relations Act was repealed and other legislation took its place. This brought back the right to strike but the 'closed-shop' provisions compelled the worker to belong to the union if he wished to work. It gave the union and thus its establishment the power to decide who should work and who should not. The changes would thus seem to have been aimed at increasing the power of the establishment rather than that of the workforce and its elected representatives.

Hence it would seem in this case that movement along the scale, towards greater freedom to withdraw one's labour, was countered by giving greater power to the union's establishment. One is left with the impression that the style of management moved further towards a more authoritarian style of management, under a supposedly pro-Labour government.

|

|---|

| Figure 6Style of Management in Individual Countries |

The left wing opposes co-operation and opposes the appointment of worker directors. Increasing nationalisation means increased state ownership and generally results in greater centralisation and more authoritarian management. But the Post Office unions have shared out among themselves worker-directorships on the Post Office board, both on the main board and on the eleven regional boards, this being a two-year experiment in union participation.

The material point is not whether it is a left wing or right wing dictatorship but whether and to what extent it is a dictatorship. What matters is whether management is authoritarian or participative. That is, what matters is whether the people are free or whether they are oppressed, whether they have the right to strike and whether they can exercise this right.

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia operates a system of 'self-management'. To a very considerable extent those who work in a workplace also own it, and this means actually control it. They elect from among themselves the policy-making body. One is elected to this body for two years and it is this body which then appoints the management.

The state of course exercises considerable influence by the amount of money it may withdraw from the enterprise's income but the enterprise has full control over what is left. The money left may be used to increase wages or to extend the factory.

There was no right to strike and this placed Yugoslavia on the scale somewhere between the United States of America and where the United Kingdom used to be, shown by the first Yugoslav position on the scale.

Some years ago strikes were made legal and Yugoslavia moved even further towards participative management, shown by a move from position 1 to position 2 on the scale (see Figure 6f). Not only are people able to withdraw their labour, but in addition they exercise a great deal of control over their own working conditions and over the future of the enterprise.

If they strike, then presumably they strike against their own management, backing the policy-making board they have elected or perhaps even striking against the policy set by this policy-making board. The right to strike is there, the workers have that power at least in principle. It is possible that they may in fact be unable to freely withdraw their labour, that the right to strike is restricted in some way.

Israel

In Israel the same Labour government and establishment had until 1977 been in control for just under thirty years. The government is a very large employer, there is a very considerable private sector but there is also a very large trade union owned sector which contains some of the largest companies in the country.

By 1973 it had become apparent that power was being concentrated in relatively few people and that even the trade union organisation had become more authoritarian. There was a strong feeling that the central trade union federation (Histadrut) does not represent the workforce as it should.

'Unofficial strikes result {10} from such neglect, drawing attention to local unresolved grievances. If there are too many unofficial strikes then trade union officials have to be made responsible for properly taking up their members' grievances with management and need to be replaced if they do not do so.

Instead, the government passed a law restricting the right to strike. Unofficial strikes are out but the Histadrut can call strikes. Local grievances are bottled up, resentment increases, the conflict becomes more severe.'

'Introducing such legislation generally results in fewer but bigger strikes which do far more damage to the economy than before. So what such a law does is to silence effective protest against the trade union establishment and to increase the power of the trade union leaders to direct and control their members. The free man can withdraw his labour as he pleases so that a basic freedom has been restricted.'

The Israeli labour law applies to essential or government controlled enterprises. It was introduced at about the same time as the British Industrial Relations Act and amounts to a move towards a more authoritarian style of management, as shown by position 1 in Figure 6g.

El Al is Israel's national airline which in 1974 carried both passengers and freight, then having the monopoly for such traffic. Let us look in some detail at two strikes which occurred one after the other, the first in August 1974 and the second which followed the first in December 1974. These strikes are relevant because this was the first occasion in which the Histadrut openly sided with the management against its own membership.

The first strike started apparently on 26th August 1974. The Company's maintenance workers suddenly called a 24-hour warning strike. The difference between management and the 500 or 600 workers centred on an overdue collective wage agreement.

The Tel Aviv Labour Court ordered the maintenance men to return to work immediately and on 1st September it was reported {11} that the State Attorney had initiated proceedings against the men's committee - but relating only to their earlier refusal or slow acceptance to obey the back-to-work orders issued during the previous week by the Labour Court. As the men were back at work but working to rule, there was apparently no way in which the law could be brought to bear against them, according to what one of the country's ministers is reported to have said.

It was also reported that the El Al management was apparently suing each of the 500 or 600 maintenance men (out of about 3,800 workers then employed by El Al in Israel) for payment of IL25,000 (about £2,275) towards the Company's losses caused by their unauthorised action.

This is open and direct confrontation between the management, that is the socialist 'Labour' party, and the workers. Management is attempting to compel the men to work whether they like it or not by using as a weapon against the men the labour legislation I have already mentioned. Management is here encouraging and promoting strife and conflict instead of co-operation and teamwork. The men were at that time apparently 'working to rule' and apparently there are no labour laws which can be used against them.

The way in which this dispute was handled must have intensified the confrontation.

Now we can look at what took place only a few months afterwards, in December 1974. It was again a dispute between the El Al management and its maintenance workers but this time El Al for the first time in its history grounded its entire fleet of thirteen aircraft on 27th December apparently with the endorsement of the Transport Ministry. The maintenance men's committee denied that they were indulging in any form of 'working to rule' or strike. It seems that the Company had got fed up with the maintenance men working to rule.

The Histadrut sent a letter to Ben-Gurion airport suggesting that the Histadrut initiate a meeting between the maintenance men and management. However, they wanted an understanding from the maintenance men that they would abide by the Histadrut's ultimate ruling. The maintenance men said that they wished nothing better than a meeting with the management, but the clause about accepting the final authority of the Histadrut was ignored.

The Histadrut then decided on Sunday, 29th December to withdraw 'union protection' from the El Al maintenance men. This was to take effect on the following day unless the workers indicated before then that they would obey the Histadrut's decisions about their grievances.

Withdrawal of Histadrut 'protection' meant that the Histadrut would not intervene if the Government issued job mobilisation orders, dismissed strikers or recruited others to replace them.

Even if the Histadrut had been afraid of legal consequences, they need not have actively opposed the men by withdrawing trade union protection.

The Histadrut's decision had far-reaching consequences, being a first step towards withdrawing union protection from workers in essential services who strike without the permission of the Histadrut.

The Histadrut executive's decision would seem to indicate that at least in this instance it has ceased to represent the workers who are its members. Instead of representing them it is attempting to impose its authority on them. The management and the Histadrut executive are supporting each other against the workmen.

The situation in Israel was complicated because the particular law concerned applies to government employees and relates to essential services but on the other hand one could consider El Al to have been a commercial company controlled by the government, with the Histadrut assisting the management (that is the government) to break the 'work to rule'.

I would not like in any way to comment on the validity of the men's case which could possibly have been most unreasonable. However, the Histadrut is here not concerning itself with mediating between workmen and management, seems to be more concerned with forcing the men unconditionally to accept the decisions of the Histadrut's executive.

A meeting on Sunday, 29th December between representatives of the El Al worker committees (which did not include the locked-out maintenance men) and the Histadrut (Labour Federation) leaders produced no results. They seem to have merely restated {12} their own positions. The workers urged the Histadrut executive to cancel their decision and apparently asked: "What have you done between strikes? What did you do to prevent the situation from deteriorating?". They claimed that El Al's management had misled the press into believing the maintenance workers were striking. "For years we asked them to set norms. But they claimed it could not be done. How come they suddenly know how long it takes to do this or that?"

The secretary-general of the Histadrut is reported to have said that their decision to withdraw trade union protection was mainly influenced by two inter-related considerations:

To deter workers in essential services from setting their working conditions themselves.

To maintain Histadrut authority.

The value of one man's work compared with that of another does depend on the service rendered and on the intensity of the need satisfied. This is discussed in more detail in two of the other reports {19, 20}. The kind of questions one has to ask are: "Whose needs are being satisfied, who is being served?" and "What is the skill involved, what is the responsibility carried?". One also has to consider the balance between demand and supply.

Directors, managers, management consultants and accountants are comparatively well-paid, the teacher, nurse, minister and police, firemen and refuse collectors, are not. The first serve the owners, the others serve the community. The value of a man's work is at present determined by the extent to which he serves those who run things, namely owners and their establishment, and not by the essential needs of the community. To the owners the value of a man's work is the lowest rate which has to be paid to get the work done.

We are now so organised and inter-dependent that it is common for the community to be inconvenienced whenever there are larger strikes involving whole industries or monopolies including state-owned or state-controlled sectors such as the British national health service or the Israeli national airline El Al.

This drives home the point that each activity is essential for the welfare of the community and leads one to consider whether differentials should not be limited and whether there should not be a common wage for all.

Pay received depends on supply and demand and on the extent to which workers can bring home to employers the value of their labour. This they can only do by withdrawing it, that is by striking.

It seems to me that here it is the Histadrut which should negotiate on behalf of its members instead of struggling against its membership on the side of the managers and owners (the government in this case).

As far as the Histadrut is concerned, the real issue is whether the Histadrut negotiates to satisfy its own criteria (whatever these may be) and then imposes its solution on the workmen or whether it negotiates till the workmen are satisfied that the best possible deal has been obtained.

The maintenance workers continued to report for work as usual at Ben Gurion airport. What they did was to remain in the shops for their normal working hours but without attempting to do any work. The Histadrut continued to demand {13} that the maintenance men would have to sign an undertaking to abide by Histadrut decisions.

There was not a 'labour dispute'. The men seem to have worked to rule which apparently and probably was not a 'strike' in the legal sense of the labour law referred to earlier on.

By 2nd January {14} the confrontation reached its end.

The management, that is the El Al executive, called for a guarantee from the maintenance workers that they would return to work and perform it properly 'within a reasonable time!'.

The Histadrut had sent a cable to the maintenance workers saying that the 'protection' would be restored if the workers agreed to fulfil faithfully their labour contract and to accept the authority of the Histadrut.

This being the national airline, the government {14} cabled the maintenance workers that they "must resume their work, according to the standards laid down by the labour contract", also saying that "the maintenance workers must accept the authority of the Histadrut and the decisions of its recognised institutions".

The men's committee now had it from both the Histadrut and from the government. The Histadrut told them also to faithfully follow their labour contract while the government (management) told them that also they must obey the Histadrut. In other words they had been locked out by their employer and had been opposed by their trade union.

What took place was that management and owners (the government) and the central trade union federation co-operated with each other to squash an 'unofficial' dispute. They did so in an attempt to enforce the decisions of the central union establishment over those of the locally elected representatives and the representative works committees, to enforce the decisions of the central establishment over that of the locally elected representatives.

The way in which owners (government), management and Histadrut (central trade union federation) co-operated with each other in my opinion clearly proves this point.

One fails to see how this confrontation in which the government, the management and the central trade union federation opposed and crushed a small section of the working force could contribute to anything but future dissatisfaction, frustration and industrial unrest throughout the country. Since then Israel has had a continuous sequence of conflict, confrontation and strikes which can be compared to the intense internal struggle which took place in the United Kingdom after the passing of the Industrial Relations Act, in both cases the direct result of moving from position 1 to position 2 (Figure 6g), of moving towards a more authoritarian style of management.

China

Every fourth person is Chinese and to this already large number of Chinese should probably be added the many Chinese who live outside China.

What the Chinese are taught to think, the way in which they are taught to behave and what they do is thus of importance to the rest of humanity. Just as it is of concern that the Japanese who make up about 3% of the world population have become the third most powerful economic power in the world, so the thought and action of the Chinese rulers, establishment and people is important to the rest of us.

In January l975 the 4th National People's Congress was held in secret and produced a new constitution to replace that of l954. The National People's Congress remains the highest organ of state power, "under the leadership of the communist party of China". The chairman of the Central Committee of the communist party assumes "command of the country's armed forces," thus ensuring that the party controls the armed forces.

However, the constitution states that the masses have the right of free speech. They may hold debates and "write big-character posters" as they did during the cultural revolution. Chinese workers again "enjoy the freedom to strike" which they have not in theory been able to do since l954.

About seven months later there were newspaper reports in Moscow about purges and deportations which took place in China following worker and peasant uprisings in several provinces because of economic problems.

About three months later there were reports from Bonn that dockers and railway workers in Shanghai, the world's most densely populated city, had gone on strike in the last few months for higher wages and better working conditions. It seems that four strikes closed the main dockyards and railway stations. It seems that radicals opposed the eight-grade wage scale endorsed by the constitution and demanded immediate moves toward an egalitarian wage. Many older workers, however, were demanding "more co-operation" from the higher-paid cadres - which is a roundabout Chinese way of demanding higher wages and better working conditions {15}.

Any Chinese institution down to a primary school or small factory had been run by a revolutionary committee consisting of veteran administrators, representatives of the younger staff and often military men as well. But during the previous few years they had been used to challenge the parallel party committees. It seems that the present leadership is emphasising control by communist party committees at all levels and it seems that the lower-level revolutionary committees, such as those in schools and factories, are to be abolished.

The lives of all citizens are in the hands of the state and it seems that the Chinese worker lives all his life inside his commune and that the quality of life - how well he is treated - depends largely on the leadership of the commune.

The Chinese worker has apparently {l6} to live where he is told to live, has to work where he is told to work, has to do what he is told to do. One has to ask for permission to leave one's work and for permission to travel.

Families are normally given food coupons which are valid only in their own province. But if one wants to travel one must also get national food coupons to buy food elsewhere.

Since then more protesting voices have been heard and there have been some demonstrations. But there have also been subsequent trials and heavy punishment for some outspoken dissidents who disagreed with the 'official' point of view.

But there has been no news of people in fact being able to strike freely as and when they want to or of successful demonstrations or strikes.

On the whole there is little if any indication that the standard of living is increasing or that any protests or strikes have had impact or caused change.

And now we have to place China on the scale of style of management. Before the l975 constitution there was no problem. Authority clearly centred at the top, strikes illegal, China placed right on the vertical line of completely authoritarian management (see Figure 6h, position 1). Following the l975 constitution there were strikes, and people were able to express their feelings through posters. There was discussion and an attempt was made to create a system of self-management which apparently rested on the people and paralleled the party control structure. It would seem to have been a move towards self-management and freedom, shown by the move from position 1 to position 2.

It seems to me that the movement was then reversed and that the Chinese people allowed themselves to be pushed back from position 2 to say position 3.

Overall it would seem after this backsliding towards more authoritarian government that China moved again a little towards a more participative form of government since there have been protests, since there have been demonstrations and strikes although so far they have been few in number and have not as yet produced noticeable change. This movement is indicated by the move from position 3 to position 4.

Japan

Japan is a democratic country. Life is in many ways restrained, stylised and formal. Strikes are legal and the workforce does strike.

In Western democratic countries pressure is exerted on the working population, persuading and compelling them to work and to serve, by the fear of dismissal, by the fear of being unemployed and by fear of the resulting hardship and deprivation. In Japan pressure is exerted in a different way. For centuries the Japanese were governed by means of a strict code of adherence to the collective will of the group. At home, in school, at work or at play, individualism is frowned upon. It is the need to conform, the fear of 'losing face', which motivates. If one does not conform then one is ostracised, if one disagrees then one of the two parties may lose 'face' (which is 'standing') and it is this which is to be avoided.

There is pointed and almost direct co-operation and team work by those at the top who put Japan's economic progress above all else. Japan, now the third most powerful country in the world, is very much looking after 'Japan Incorporated' with government, owners, and other institutions co-operating closely together. Profit was of secondary consideration to Japanese companies and shareholders accepted minute profit margins, the general aim being 'seiko', which is 'growth'.

The Japanese do not start a project until some kind of agreement has been reached. For example a larger capital investment programme would be discussed by the company, by the union, by the ministry, with the banks and of course within the enterprise. It would be discussed extensively until it takes a firm form.

The discussions within the enterprise are called 'Ringi'. The style of management would appear to be strongly authoritarian but paternal. The Ringi process is time-consuming and formalised but aims to involve younger and junior employees in the decisions and in the fate of the company.

Sharp changes are taking place in the life of the country and in the economy and there is a felt need for speeding up the decision-making process. All decision cannot be made at the top, delegation of authority is increasing and the scope for independent decision-making is being widened. Group decision-making is being modified in the light of increasing size and complexity of modern organisations so that instead of a large group making decisions concerning a broad area of policy or operations, small groups make decisions concerning areas of particular concern to them and these are then approved by their superiors. Participation in policy setting is being downgraded into implementing policy, and this is a downgrading of participation, of the level of decision making, by employees.

It seems that large and important companies are on the whole not allowed to go bankrupt. Creditors, shareholders and other financially interested parties all participate in the reorganisation of the company <2>.

To be laid off does not mean being made redundant. Workers in large companies are likely to be turned to other work or are sent home while receiving full pay and benefits <3>. This is on the whole soon heartily disliked by Japanese workers who do not feel comfortable if they do not work.

There is much life-time employment in one company. Workers' homes are likely to be owned by the company, all will go on holiday together as a group. The company's influence is felt in many areas of the workers' lives, loyalty to the company is fostered (for example all company workers are likely to wear the same lapel badges) and conformity is expected.

About one-third of the employed labour force are members of trade unions, distributed through something like 60,000 unions, based mostly on enterprises. Such enterprise unions negotiate primarily at the factory, site or enterprise level, although there are some negotiations between national trade union federations on the one hand and employers' associations on the other.

Roughly three-quarters of the trade union membership are in the private sector and exercise the right to free collective bargaining.

Loyalty to the company is strong and many workers normally strike during their lunch break, in this way making their opinion felt. They would not do so if it were not effective and this implies that management takes note.

Then there is the 'Shunto' (spring offensive) which is used to deal with the annual wage claim by establishing an acceptable general increase. A certain selected group of employees or union goes on strike. The results of that strike are gradually used for the bulk of the settlements throughout the country.

The general picture would appear to be one of democratic government and authoritarian but paternal management, combined with a system of management consultation and co-operation which is sound in principle.

The cost to the Japanese of authoritarian management is already considerable. For example, waste products were dumped over a considerable number of years by a commercial concern into the Bay of Minamata with tragic results to many of the local population who suffered organic mercury poisoning in severe degree through eating polluted fish caught by the local fishermen. Fish is a staple diet. The Japanese eat fish rather than meat and fishing is a source of livelihood for many Japanese. Much of the fish around the shores of Japan is affected by pollution and the Japanese government has apparently already issued guidelines advising people to limit the amount of fish they eat.

But there are also bitter confrontations between employees and employers as a result of the impact of foreign ideology. There are also demonstrations, at times violent, concerning popular protest issues.

Leaders of left-orientated Japanese unions are said to regard co-operation with capitalists as impossible and confront for the sake of confronting, in line with other marxist movements.

To them it appears as if enemies cannot co-operate because they would be traitors to their individual ideologies and they apparently eliminate dissenters from among their own leading personalities {17}.

Seeing everything according to pre-conceived ideas, according to what one is told to do by those above, in terms of black and white or right and wrong, is typical of the authoritarian mind. Democracy rests firmly on voluntary co-operation between informed and knowledgeable citizens and groups able to evaluate differing points of view according to the situation existing at the time.

Hence Japan is fairly authoritarian in its style of management. There is little or no power sharing. People have the right to strike but striking is limited by the Japanese equivalent of the Western fear of the sack, by pressure to conform. Hence I put Japan close to the UK but consider it to be somewhat more authoritarian (see Figure 6i).

Germany (Federal Republic)

Legislation about striking would appear to be similar to the American Taft-Hartley Act and to the British Industrial Relations Act which caused such intense confrontation in the United Kingdom when in the end much of British industry was reduced to working a three-day week.

But outstanding is the 'Bestimmungsrecht', the legal requirement for the policy-making body to contain worker representatives.

West Germany has had worker participation in the coal and steel industries since 1951. The extent of representation was 50:50 but apparently in larger companies the shareholders had two-thirds and workers one-third of the votes on these policy-making (that is supervisory) boards. The system has worked well and helped to maintain good industrial relations in this key area.

A new law passed in l976 extended the system to cover another six hundred large enterprises, each employing more than 2,000 workers, outside the coal and steel industries. It gives workers equal representation with shareholders on supervisory boards.

Supervisory boards meet only four times a year, take all strategic decisions and appoint the management board which handles day to day operations.

The chairman of each supervisory board must be elected by two-thirds of the board's members and can cast two votes in the event of a voting deadlock. This gives the chairman the power to decide, and since the procedure for electing him seems to be weighted in favour of the shareholders, the workers are still at some disadvantage.

This system cautiously acknowledges that both employees and employers are vitally interested and concerned about the well-being of the enterprise and constitutes a considerable transfer of power to the workers' representatives.

I have the impression that German management itself is fairly authoritarian with possibly less protection for the worker in his work place but perhaps greater unemployment benefits and greater social security payments.

It would seem that the benefits of economic success have been shared out and that the standard of living is very high.

It seems to me that all this puts Germany between the USA and Yugoslavia, probably nearer Yugoslavia than to the USA since the recent coming into effect of the l976 Bestimmungsrecht which moved Germany's position from position 1 to position 2 on the scale (see Figure 6j).

THE CHANGING PATTERN

We can now consider together all the countries we have looked at and Figure 7 shows both their present style (Figure 7A) and what it was like before, that is what it was like roughly up to ten years ago (Figure 7B).

|

|---|

| Figure 7Style of Management in Different Countries: Changes over Ten Years |

There is a considerable difference. Previously the countries we have considered formed two clearly separated groups. The first consists of strongly authoritarian governments which include dictatorships of the left as well as of the right. The second consisted of democracies with the exception of Yugoslavia which is a special case by reason of its applied 'self-management'. The UK and Israel we considered to be adopting a rather more participative management style than the other democratic countries.

Interesting is that the later picture is significantly different. The last ten years saw a distinct movement towards greater participation and power sharing.