Dodging the (Confederate) Draft Through Postal Service. (original) (raw)

Early in the Civil War, most Texans optimistically assumed life would be easier as citizens of the new Confederate States of America, but they soon discovered that what some called �the old government in Washington� had actually managed to do some things right over the years.

Take postal service, for example. Before the war, a Texan could go to any of hundreds of post offices in the state, buy a three-cent stamp, affix it to an envelope and be relatively assured that its contents would be delivered anywhere within 3,000 miles in a timely manner.

If Southerners used to such service had the same expectation of the Confederate post office, which came into being on Feb. 21, 1861, they soon discovered the truth of the old adage about being careful what you wish for.

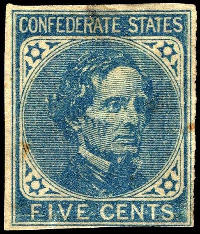

Despite the creation of a Confederate postal service, the U.S. continued delivering mail in the South until May 31. The CSA service technically began operation the following day, but it had no postage stamps for its post offices. In fact, the Confederate post office department had no stamps to distribute until that fall. To compensate for that, rebel postmasters throughout the south began issuing their own stamps.

|

Confederate States five cents stampsCourtesy wikimedia commons |

|---|

Texan John H. Reagan, the Confederate postmaster general, tried hard to make mail delivery efficient during the war, but it never compared with the U.S. postal system. If the Confederate postal service couldn�t even get stamps printed in a timely manner, it follows that mail delivery may not have been as dependable as it had been under the U.S. Post Office Department.

Thanks to stamp collectors, the history of the CSA postal service and its stamps has been fairly well documented. But Confederate mail carriers have received little attention.

Heinrich Wilke came to Fredericksburgwith his brother in the late 1840s and earned his living as a wheelwright. Leaving Prussia (future Germany) for Texas proved to be a good decision for Wilke and his family, at least until Texasdecided to secede from the Union in 1861.

Like most Germans, who either did their own work or hired it done, Wilke surely had no regard for slavery. And again like most German-Texans, he had little interest or inclination in getting involved in what he considered someone else�s fight.

During the Civil War, according to family lore, he worked as a Confederate mail carrier in Gillespie County. When he began his service, how much the government paid him, and what route he traveled may or may not lie buried in the records of the Confederate Post Office Department held by the National Archives.

But one thing is as clear as the water that then flowed in Fredericksburg�s Barons Creek: Wilke did not take on the job of delivering the mail out of any sense of duty to the Confederacy. Sure, the ability to communicate by letter was important to the people in his part of Texas � as well as anywhere else � but his intent is clear in light of Confederate conscription laws.

Wilke did not want to get drafted into the rebel army. The Confederate conscription law specifically exempted mail carriers from any obligation of military service.

Not that carrying the mail in Gillespie County back then would have been a risk-free occupation. With the U.S. Cavalry long gone, and most Texas men serving in the Confederate military elsewhere in the South, hostile Indians posed a constant threat along the frontier.

Beyond the danger of losing his scalp and more, Wilke had to keep a wary eye out for members of what came to be called the Hangenbund, a gang of Confederate sympathizers who cheerfully lynched numerous pro-Union German-Texans in Gillespie County. While Wilke worked for the Confederate government, he was not a Confederate at heart.

The interest in mail carrying as an avocation during the Civil War was not unique to the German settlements in the Texas hill country.

J. Stephen Lay of Marble Falls, a retired public relations man who began his career as a reporter for the Fredericksburg Standard, says he remembers hearing about a man who worked as a Confederate mail carrier in Galveston.

�The story is that he paid the local postmaster $20 a month for the job,� Lay says. �He wasn�t interested in a salary.�

Lay says he doesn�t remember the man�s name and never substantiated the tale, but given the circumstances, it has the ring of truth. Whoever he was, that Civil War-era postman plainly preferred to take his chances delivering the mail rather than ducking Yankee bullets.

�

Mike Cox- February 13, 2013 column

More "Texas Tales"

Related Topics: Texas History |

People| Columns | Texas Towns | Texas

Books by Mike Cox - Order Now

Custom Search

Book Hotel Here - Expedia Affiliate Network