Woman,Sun,Flowers,Courage (original) (raw)

THE WOMAN, THE SUN, THE FLOWERS AND THE COURAGE

HALBERT HAROLD HOLLOWAY

rena-Alice rose and sat on the edge of her bed. With deft, practiced thoughtless movements, she swept her long brown hair into a thick, round sphere on the back of her head. It was another day. There were cows to milk at dawn, and at dark. There was food to cook and there were vegetables to irrigate. There were fields to be plowed and hogs to be fed. A fence needed mending, and some chickens had to be butchered before Wirt came home. When Wirt came back from Cuyama, they would have a big dinner. She missed her husband. She missed his gaiety, his never-ending dreams, his strength, his ability to laugh, and his ability to weep. Weaver and Ben would milk the cows. Weaf, her oldest son, would soon be leaving, and her small, quiet, sensitive son Ben would take his place. Ben would take Weaf's place before his bones were grown and before his mind wanted to think mature thoughts, man's thoughts. Yes, Weaver and Ben would milk the cows. And Mabel would water the vegetables, and she would coerce Luella into feeding the hogs. Beautiful, red-haired Mabel who threw her body forward with will as she walked; with head high, and her glance a bit hard. Mabel was hard with everyone, even with herself. Beautiful, brass-like Mabel had to be hard. And quiet little Luella with her long blond bangs that constantly fell into her eyes, and her beautiful strong mouth and white teeth, Luella, who was always laughing or crying, always giving, who would lug the waste out to the hog pen, and perhaps Mabel would help her.

rena-Alice rose and sat on the edge of her bed. With deft, practiced thoughtless movements, she swept her long brown hair into a thick, round sphere on the back of her head. It was another day. There were cows to milk at dawn, and at dark. There was food to cook and there were vegetables to irrigate. There were fields to be plowed and hogs to be fed. A fence needed mending, and some chickens had to be butchered before Wirt came home. When Wirt came back from Cuyama, they would have a big dinner. She missed her husband. She missed his gaiety, his never-ending dreams, his strength, his ability to laugh, and his ability to weep. Weaver and Ben would milk the cows. Weaf, her oldest son, would soon be leaving, and her small, quiet, sensitive son Ben would take his place. Ben would take Weaf's place before his bones were grown and before his mind wanted to think mature thoughts, man's thoughts. Yes, Weaver and Ben would milk the cows. And Mabel would water the vegetables, and she would coerce Luella into feeding the hogs. Beautiful, red-haired Mabel who threw her body forward with will as she walked; with head high, and her glance a bit hard. Mabel was hard with everyone, even with herself. Beautiful, brass-like Mabel had to be hard. And quiet little Luella with her long blond bangs that constantly fell into her eyes, and her beautiful strong mouth and white teeth, Luella, who was always laughing or crying, always giving, who would lug the waste out to the hog pen, and perhaps Mabel would help her.

Martha was the most beautiful. There was a soft, tender loveliness to her that exaggerated Mabel's striking beauty when they were together. Martha so lovely, yet who talked an incongruent, humorous baby talk because she was deaf, and because her throat had been cut by glass. Everyone watched after Martha. Ben watched after her. He was the tender one. Like his father, he could stand in a moment of beautiful thought. Ben and Alice "Aleece" because that was the British pronunciation, and Irena-Alice was British. She and Aleece would water the flowers at sundown. They would work in the house together and read poetry together from the shabby little book that contained such beauty.

They would go out at sundown and water the flower garden. Irena-Alice and Aleece would walk along a little path, winding through the sage brush and the alkali splotches until they came to a sheltered place, and they would water the flowers. In the Spring, the flowers would bloom and be beautiful and gentle - appearing in the desert plain. There would be a little spot of beauty in the desert plain. Irena-Alice had to eke out beauty from the California farm life, beauty from her husband's simple stubborn, enduring sincere love, from her children, from Aleece and Ben, from Mabel's hair, and Lou's unselfishness, and the tender pathos of Martha's enthusiasm expressed in little, hard-earned spurts of her words. Her husband's love was like flowers in the desert. Her children were her flowers in the desert.

She rose from the bed and walked across the room. She threw her right side as she walked. A buckboard had pressed into her side, and the pain seemed killing, and the doctor said that she would never walk, but she did walk, and she bore more children, and again there was pain. But her husband was there at the births, bringing into the world the creation of their love, bringing it from the warmth of her into the world. And then he would gently arrange her hair around her head and wash her face and tell her that he needed her presence, her voice, her laugh, her mind, her love so much.

Why was she remembering so much? Why was her mind going back and forward all around in her soul? She went into the kitchen, Breakfast must be made for Weaver and Ben, and soon Aleece would make her sisters rise from the bed. Mabel would scold Aleece. Luella would slowly put on her shows, and Martha would wash her and go look at the baby. Irena-Alice put more water on the oatmeal porridge that had been cooked the night before and she made a fire. She went over to the window to get salt and sugar. The sun was coming up in the East, but it was not beautiful. It was rising up above the valley, and it would burn down onto the sage brush and the land and the buildings. It must have been the same color as Milton's burning plains of hell that she had read about when she was in school in England. The day would be long, and the heat would sap the strength out of the bodies of the family. But the necessary work would be done. She hoped that the burning sun would not kill her beautiful flowers in the desert.

Then evening would come. It would be twilight until nine o'clock, and the sky would be blue, pale blue, and it would change to dark, dark blue, and it would seem that the stars were trying to reach down to touch the earth. Her family would stay out of doors, and there would be games and laughter, and her husband would be the leader in the games - stocky, strong, bearded, courageous in this dry land, teaching his children to laugh and to sin and to have a soul like his soul. And he would smile a beautiful smile that could be seen through the thick black beard, and his eyes would twinkle. And Weaver and Ben, especially Ben, would smile the same smile. The evening time was the best time, the happy time, after she and Aleece had gone to water the flowers, and after the family had eaten the products of their soul. Wirt must be back tonight, she thought. If not, there would be laughter, but the most important, the most warm laugh would be missing.

She worked in her hot kitchen thinking that. And she and Aleece would find time to read poetry today.

She saw Weaver. tall, big, and strong, walking up from the barn. He was carrying Ben in his arms, and Ben didn't have his hat on, and his white blond hair fell down. She moved as fast as she could to the door, and opened it for her sons. Ben fainted, Weaver said, and he carried the little boy into the bedroom. She followed him, and felt the forehead of her son, and it was hot, hotter than the sun would make it, or than the work would make it. She took his clothes off and covered him up and told Weaver to waken his sisters. Aleece and little Luella were the first in the room of the sick boy. And then Martha. Mabel came in after her. Aleece said that she would help her mother that day and went over and touched her brother's head. Mabel told the other girls to do their usual jobs, and that she would finish milking the cows while Weaf was gone. Mabel took the most difficult thing to do, for it was the easiest for her. It was proud, gentle Aleece who would be by Ben's bed.

Irena-Alice saw her large son go out to saddle the horse, and she saw him turn its head toward Bakersfield for the doctor. He would be back by dark. Mabel ran out through the hot morning sunlight and grasped the rein of the horse and spoke animatedly to Weaver. The mother didn't hear what she said, but she knew that it was about Ben.

Aleece tried to make Ben comfortable. The little boy was so still, so quiet. Irena-Alice told her that there was little to do, little to do except wait, - wait and watch and feel helpless, feel futile, and pray.

Irena-Alice looked out over the little farm from the clapboard house that her husband had built. It was fertile land, it was good land; it was a land for building and dreaming and making beauty. But it was a ruthless, hot land of work and illness and death. She had lost a son in the past. Before, when he was very young, Weaver drove his older brother to the town to the doctor, and the older brother lived. And he painted. He painted Milton's sun-up and made it beautiful. He painted the sage brush and made it beautiful. He painted little flowers by the sage brush and made them beautiful. His hands were large and strong like her husband's, but they were also gentle in their gentle work of art. He grew tall and strong and worked on the ranch and painted. He earned a scholarship, and he was going to San Francisco to learn about painting. It was a new land growing and new ways, a hard land to travel in and her son who could make beauty was killed.

And now there was this son, and his life, and his beautiful smile, and his hopes. She must help her son. She must make him live, and see beauty, and be happy and create in this new land, and have children. For her husband and for herself and for the child, she must help this child live.

The day passed, and she was tired, and her daughters were tired. Martha made her some tea and took it to her, and Martha was quiet. The little boy lay still on the bed, still and quiet and white and hot and covered, and Aleece held his hand, and Mabel stared at him and left the room to do something, and Luella fell asleep. And they all hoped that his eyes would open. Irena-Alice waited and looked out of the window for Weaver and the Doctor.

The sun was going down in the west, slowly, stubbornly, giving up its rieign of heat of the San Joaquin. Mabel came into the room. Thank God, she said, Weaf was coming up the road with the doctor. It was the old doctor who had lived in Bakersfield ever since the railroad had come to town.

The doctor came in and examined Ben and drank some tea, remarked on the book of poetry on the table, and chatted for a minute. Then he told Irena-Alice that it was necessary to slit her son's wrist to ease the fever, the fever in this hot, hot land.

Irena-Alice was frightened. She had never felt fear like this before. She was frightened once when she spilled a hot vat of pig grease on her front and scalded the life out of the new life forming in her womb. And she was frightened during the first birth, more than during the other births. But her husband was there and he was the father and the doctor and held her head and she wasn't so frightened. But this was the fear of decision. She didn't wanter her little boy to die. And she didn't want her decision to be the cause of his death. She wished that her husband were there to take her hand and tell her that it must be done. But he wasn't there. She looked at Aleece who so resembled her, and Aleece said nothing. She looked for Mabel, and she was in the kitchen getting something for the doctor. Mabel was beautiful, active and sensual. Mabel would only act. Irena-Alice looked to Weaver, and he said nothing. But his eyes were like her husband's eyes, and she knew that he wanted her to say yes.

Yes, take the knife, the sharp, keen blade and press it across the thin, white wrist, and let the pale red of life flow out. She shook her head a little yes and walked in a stubborn body-throwing manner to the window, and touched her thick hair, and shut her eyes.

She knew that Weaver had helped the doctor, that her quiet intelligent son held the basin in his large hands, and the pale red flowed into it, and that he handed the doctor the dressings, and heard the doctor say that was difficult to do, and that he would spend the night there. And it was Weaver who took a new clean sheet and tore it into long, straight bandages so that more blood would not come out. And Mabel helped him to do that, and Martha fixed dinner, and Aleece bathed Ben's face, the face of the little boy who was so white, and so quiet, and whose eyes had been closed for so very very long.

Her children were strong as their father and as strong as she had become. It was the terrible valley that made them strong, that was part of them, as the heat was part of them and as the little flowers in the sheltered places were part of them.

She wanted her little boy to live. There would be more children, but wanted this child to live. He was working in the fields one day, and he picked a bouquet of little valley flowers, pale, blue little flowers, so small that it was difficult to hold them, and he took them to her and he smiled. And he was beautiful like the flowers, for he saw and felt beauty in his child's life on this hard little farm. He could dream: like his father, he could look at the stars and dream, and he was gentle. Yet he was hard. Such a little boy, she thought, yet he was hard, he didn't cry anymore, he didn't complain. Like her, he hated pain, he hated ugliness; he hated unkindness, but he would not complain. He would just remain quiet and kind and trustworthy, and now and then, he would go down to the flower garden in the sheltered spot, and in a sheltered spot in his soul he nurtured beauty, greater beauty than his brother had painted. It was a beauty expressed in living, in being, in doing, in hoping, and in dreaming. She wanted her little boy to live.

The deep blue left, and iron gray came and hung over the valley. Irena-Alice sat in her chair and stared out. Aleece was there with her, and the little boy was still, so still. The iron-gray was changing to yellow. The little boy opened his eyes and raised his hand and asked for a drink of water. Aleece ran fast, hard, into the kitchen, and Irena-Alice heard the pump handle go up and down so hard, and her daughter came back and handed the water to her, and Aleece started crying and laughing and feeling physicially all of the emotions that were welling up in her. Irena-Alice felt them too, but she nursed her son, and tears came. Aleece ran into the other rooms and awakened her brother, and her sisters, and they all crowded into the boy's room, and the boy smiled at them, and they laughed a little, were silent a little, and prayed, and Irena-Alice prayed and smiled and cried. And later, the buckboard was put into the barn, and the stocky, strong, dark-bearded man came into the room and stood by his wife and his sons and his daughters and looked at his wife, and she knew that he knew that which was in her soul.

The sun had come up high. It was not Milton's sun, but an orange, beautiful, life-giving sun - that sun that gave life to the little flowers in the sheltered spot.

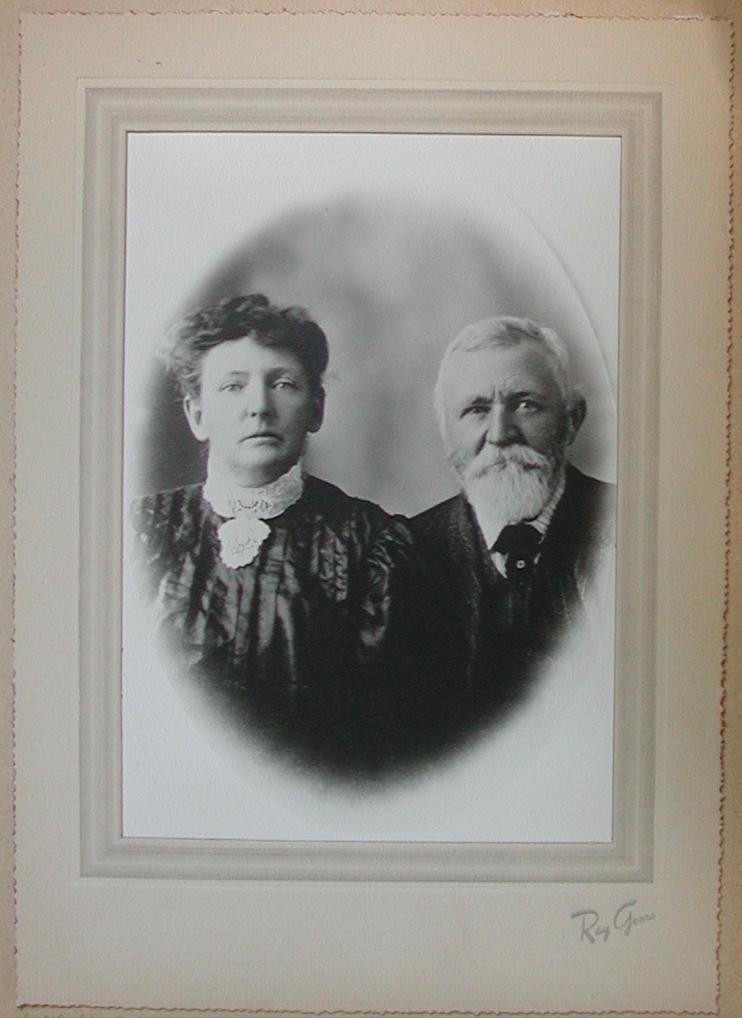

Found in an old box in Uncle Dutch's shack at his goldmine, Hawthorne, Nevada. Dutch, with his aged parents, Irena Alice and Wirt Holloway, Bakersfield, California.

_____

In fact, Irena-Alice Culbert Holloway was Canadian, rather than 'British', and had studied at the Nova Scotia Academy, where she learned to embroider wild flowers in tapestries and to read Milton. She was sent out to California for her health, meeting Wirt at a dance in San Jose. He had gone from Kentucky, after they sold their slaves, to Texas, where they herded cattle, finally to California. Later the children in the family of twelve included Bertha Gertrude, called by her father the name of his favorite slave in Kentucky, Chloe Mae, and Halbert Harold Holloway. Ben would call his child by his second wife that same name, Halbert Harold Holloway II, because this was the one brother who attended university at Berkeley (the two sisters Aleece and Mabel already had studied at San Jose State Normal School), becoming a World War I Ace but who never married. Hal wrote his doctoral dissertation on his uncle of his same name. Indeed, of the twelve children born to Wirt and Irena-Alice, only Ben had children who survived him, Hal and Luella, survived in turn by Marci Munding, David and Ronald Seidel, Richard, Colin and Jonathan Holloway, and their children Akita, Jasmine, Caroline, Robin, Rowan, Aurora, Asha, and Rubinia. We often visited Aunt Leece in her apartment in San Francisco filled with oriental carpets, Carrara marble fireplaces, Mission silver, Della Robbia pottery, and European water-colors, for she married George Fernald, President of the Fernald Steel Company, and made the Grand Tour. She gave me Irena-Alice's embroidery of wild flowers which I then gave to my granddaughter Caroline to treasure as a keepsake, along with jewelry from my family, the amber beads from the Russian Baltic my great grandfather James Roberts gave to his daughters, coral beads from the Mediterranean. The family of twelve are buried with their parents in the Holloway plot in Bakersfield. I published Hal's story in Reed, the creative writing magazine at San Jose State College, May 1956, having read it when I was seventeen and he was twenty-five, marrying him when I was twenty and he twenty-eight. Always I yearned for a daughter to be calledIrena Alice, but instead I bore him three fine sons, for which he could not forgive me.