The UnMuseum - Fabulous and Foolhardy Flyers II (original) (raw)

Those Fabulous and Foolhardy Flyers II

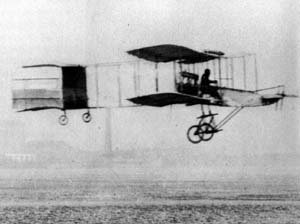

In 1907 Henry Farman takes the Deutsch-Archdeacon prize for a public flight of more than one kilometer in length.

Part 2: Flight from Wilber to War

On a wind-swept beach at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina on December 17th, 1903, history records that the Wright Brothers made the first heavier-than-air-flights. The longest of these flights was only an 852-foot hop, yet scarcely 6 years later aviators would be braving the 20-mile wide English Channel. By the middle of World War I, aircraft would have matured into fighting machines capable of penetrating hundreds of miles behind hostile enemy lines. In less than 15 short years the airplane would move from an inventor's toy to a weapon of war.

Early European Aviation

Much experimentation with early aviation occurred in France. The first manned hot-air balloons were built by the Montgolfier brothers in 1783. In 1884 a French inventor built the first successful dirigible. In 1890 Clement Ader, a French electrical engineer, created a steam-powered heavier-than-air machine that managed a brief uncontrolled hop. Despite Ader's success, at the beginning of the 20th century most French would-be aviators, with the one exception, seemed to be focused on lighter-than-air research rather than heavier-than-air flight.

That exception was Captain Ferdinand Ferber, an artillery commander whose interest in aviation had been kindled by the gliding experiments of Germany's Otto Lilienthal. Ferber started corresponding about aviation with Octave Chanute, a friend and counselor to the Wright Brothers. Later, Ferber exchanged letters with the Wright Brothers themselves and developed a great respect for them. Ferber, in turn, lectured and wrote (often under the pen name of Monsieur de Rue) about aviation in Europe and influenced many would-be aviators there, including a man named Earnest Archdeacon.

Archdeacon, a Frenchman of Irish decent, wanted France to be first in flight and helped found the Aero Club of France. After hearing of the Wright's success in 1903, Archdeacon (along with Henry Deutsch de la Meurthe) put up a prize of 50,000 francs ($10,000) to go to the first aviator that could publicly fly a heavier-than-air machine around a one kilometer course and land it safely.

By 1905 the Deutsch-Archdeacon prize was still unclaimed when unbelievable news reached Europe from the United States: In Ohio the Wright Brothers had flown a plane they dubbed the Flyer III as far as 24.2 miles over the Huffman Prairie (which was the equivalent of 39 kilometers). The debate that followed at the Aero Club was lively. Captain Ferber accepted the reports as true while Archdeacon refused to believe them. Archdeacon even issued a public letter to the Wrights including this challenge:

I take the liberty of reminding you that there is, in France, a modest prize of 50,000 francs bearing the name 'Pix Deutsch-Archdeacon,' that will go to the first experimenter who flies an airplane in a closed circle of not 39 kilometers but only one kilometer. It will assuredly not tire you very much to make a brief visit to France simply to 'collect' this little prize.

The Wrights, always more interested in the business of selling airplanes and protecting their patents and design secrets than in what they called "circus" flying, did not even respond to the challenge.

It wasn't until 1906 that a European made his first flight. Brazilian-born Alberto Santos-Dumont was a short, slim, dapper, man rich from the profits of his family's coffee plantation. As hobbies he had raced motorized tricycles and flown primitive dirigibles. In 1904 he began experimenting with gliders and in 1906 completed a powered flying machine dubbed a canard in French because it looked like a duck. It had a 24-horsepower engine and a box-like rudder and elevator that jutted out from the front of the craft like the head of a waterfowl. Santos first tested it by dropping the craft from his dirigible. In September, after replacing the engine with a more powerful one, Santos managed to get the plane to rise off the ground and hop less than fifty feet. About a month later a flight of 197 feet was made and on November 12 Santos and his plane flew 722 feet.

The news electrified Europe, but the Santos' record was still less than the Wrights had achieved on their first day of flight in 1903.

In 1907 a man named Henry Farman, son of an English newspaperman based in Paris, became interested in aviation. Farman decided he would be that man to win the Deutsch-Archdeacon prize and ordered a plane from the newly-founded airplane manufacturer Vosin Freres. The plane he ordered had a reputation of being difficult to fly, so Farman (who would later go into airplane manufacturing himself) added a front rudder, cut the tail down and adjusted the trim. Being satisfied with his changes, he went after the prize on January 13, 1908. The flight was slow and far from graceful. European aviation had yet to discover the Wright's secret to making a banking turn through warping the aircraft's wings. Even so, Farman won the prize and Europe's admiration by completing the course in one minute and 28 seconds.

A Wright Brother Goes to Europe

By 1908 the Wright brothers began to have some success at selling their airplanes and it was decided that Wilber should travel to Europe to demonstrate their model "A" plane to French businessmen that were interested in licensing the design. When Wilber arrived in France he found the plane he'd shipped over was damaged (apparently by customs officials when they were examining it) and would take weeks to repair. Wilber got along well enough with the local workmen he'd hired to assist him, but was annoyed by the French press who tried to snap unauthorized pictures of the flyer.

By August 8th, though, the plane was repaired and ready for a short test flight. A crowd (including some of Europe's leading authorities on aviation) gathered at a race track near Le Mans some 115 miles southwest of Paris. Among them was Archdeacon. The flyer was readied, and after a false start ran down the wooden track the Wrights' used for a runway and lifted into the sky. Aviation writer Francois Peyrey later wrote they watched "the great white bird soar above the racecourse and pass over and beyond the trees. We were able to follow easily each movement of the pilot, note his extraordinary proficiency in the flying business..." The flight lasted only one minute and 45 seconds but left not doubt in the minds of the observers that the Wrights had solved the problems of controlled flight with astounding success. The flight, and others that would follow, ensured the formation of Wright-licensed companies throughout Europe.

The demonstration also helped European aviators understand how to modify their own planes to get greater control. In 1909 the British newspaper, the Daily Mail, laid down a challenge that now the bravest aviators might consider accepting: A flight across the 21 miles of the cold waters of the English Channel. The prize would be a thousand English pounds ($5,000).

The English Channel Challenge

The press asked Wilber Wright if he would attempt the channel crossing challenge. He currently held the record for the longest continuous flight: 1 hour, 31 minutes and 25 seconds. This was more than enough time necessary to cross the channel. Wright was not interested putting the challenge down as a "useless risk."

Louis Bleriot sits in his aircraft waiting for his attempt to be the first aviator to cross the English Channel.

Others thought otherwise. In the end two men would compete for the prize: Twenty-six year-old Hubert Latham, a Frenchman with an English background, and Louis Bleriot, a longtime French aviator with an impulsive spirit.

Latham, rich and handsome, had led an adventurous life. He raced motorboats and hunted big game in Africa. Just that year he had taken up the sport of flying and had already held the record for flying endurance in a monoplane: 1 hour 7 minutes and 37 seconds. He flew an Antoinette IV, a slim and graceful aircraft designed by Leion Levavasseur.

The engine in the Antionette was also designed by Levavasseur and had many advanced features including fuel injection and a crankcase made of aluminum. Despite this, the engine had a habit of cutting out in mid-flight, something that would plague Latham in his attempt to win the prize.

His opponent, Louis Bleriot, was perhaps the most erratic of the early aviators. Bleriot, easily recognized by his mustache and prominent nose, used the funds from his prosperous automotive accessories business to pursue his interest in flying and designing airplanes. He operated in a reckless and haphazard manner, trying one idea after another. Some flew, but almost half never got off the ground or crashed immediately. Some of this was due to his unorthodox design, but much of it was because, according to his contemporaries, he was a poor pilot. "As soon as we had fixed up a plane the boss, burning with eagerness to succeed, would try it out right away, without paying the slightest attention to air currents," recalled one of his mechanics.

By the time of the channel challenge Bleriot had spend almost all of his fortune on flying machines. He was also hobbling around on crutches as he recovered from a burned foot. He had, however, a working airplane he'd designed designated the Bleriot XI. It wasn't nearly as elegant as the Antionette, but it had one feature that would prove critical for the trip: an engine designed by Alessandro Anzani. The engine was crude, half the power of the Antionette's and it rattled and spit oil out on the pilot with every stroke. It had one redeeming virtue, however. It kept running and running.

Latham tried his first attempt at the channel on July 19th. All was well for the first seven and one half miles until the Antoinette's engine stopped and it glided into the water. Latham was rescued and vowed to try again with a new plane.

The weather turned bad and neither pilot had a chance to fly until July 25th. Around midnight the night before the wind began to slacken and the Bleriot camp came alive. By 2 AM the air was clear and calm. Despite this Bleriot wasn't in the mood to fly. "I would have been happy if they'd told me the wind was blowing so hard there was no point in trying," he said later.

But the weather stayed calm and the plane was readied. Bleriot took it up for a test spin and found no problems. At 4:41 AM the sun rose and Bleriot took off. By mid-channel he was doing so well that he outdistanced the ship escorting him. It was soon lost behind him and all Bleriot could see was the ocean all around him. A wind started sweeping him northward past and he might have flown into the North Sea if he hadn't spotted three ships heading toward the port city of Dover. Bleriot soon found the famous white Dover cliffs and landed at an opening in them near the castle. Waiting for him with a French flag was Charles Fontaine, a French newsman. Bleriot had crossed the channel in 37 minutes while Lathem, still asleep when Bleriot had taken off, had never gotten off the ground.

The Rheims Airshow

Bleriot was a hero both in his native France and England. A month later he appeared as the star attraction at the world's first organized aerial competition at Rheims, France. The show at Rheims drew aviators from all over the world. Acres of grainfields had been cleared to build what was termed an "areopolis" consisting of grandstands, hangers, restaurants, and a ten kilometer flying circuit. Competitions included the Grand Prix for distance with a 50,000 franc prize and the International Aviation Cup (with a 25,000 franc cash award) for speed. Newspapers reported that "The air was thick with areoplanes." and that it was "a spectacle such as has never before been witnessed in the history of the world."

Many of the planes involved in the Rheims airshow were exhibited the following month at the International Exposition of Aerial Locomotion in Paris at the Grand Palis.

The Wright brothers, never interested in racing, abstained from the show. However, America was represented by Glenn Curtiss. Curtiss was a mechanical expert who had a self-professed craving for speed. He raced motorcycles, designed engines and in 1906 had tried to make a deal with the Wright brothers to have his engines used in their planes. The Wrights weren't interested. Curtiss had picked up the flying bug and in 1907 joined with Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, to form the Aerial Experiment Association. The A.E.A's aim was to make a working airplane, but they had to try to do it without infringing on the Wright's patents for controlling the craft by warping the wings. By 1908 they were making short hops with a plane named the Red Wing. On the 4th of July that year Curtiss used another A.E.A. plane, June Bug, to win Scientific American's $2,500 silver-trophy for the first public flight of a plane over a one-kilometer course (a prize that the Wrights could have won years earlier, if they'd been interested).

After the A.E.A was disbanded, Curtiss went into the airplane building business with August Herring. This immediately drew the attention of the Wrights who accused Curtiss of patent infringement and legal battles started that would continue between them for many years. Curtiss took the first design of the new company, a plane called the Golden Flyer, to Rheims for the competition.

Curtiss hoped he would do well in the speed competition, but was discouraged when he heard that Bleriot had installed a huge eight-cylinder 80 h.p. engine on his new Bleriot XII aircraft. Curtiss' mechanic, Tod Shiver, reminded Curtiss how he'd succeeded when he was racing motorcycles. "Glenn, I've seen you win many a race on the turns."

Curtiss had only one irreplaceable airplane and avoided competing with it until the speed competition for several good reasons. "At one time," he later recalled, "I saw as many as 12 machines strewn about the field, some wrecked and some disabled and being hauled slowly back to the hangers, by hand or by horses." On the morning of the race, Curtiss took the Golden Flyer up for a test run. He hit a rough, turbulent updraft that pitched his plane around the course. He was surprised to find that when he reached the ground that his time around the course had been the shortest yet recorded and reached the conclusion that the turbulence somehow had added to his speed.

After finding this out he decided to take his turn at the course immediately to try and take advantage of the turbulence. "The shocks were so violent indeed that I was lifted completely out of my seat and was only able to maintain my position in the aeroplane by wedging my feet against the frame." Curtiss completed two circuits around the 10-kilometer course in 15 minutes and 50 seconds with a speed of 46.5 miles per hour, beating Bleriot's time later that day by 6 seconds.

Exhibition and Competition Flying: Glory, Gold and Death

The Rheims show was so successful that the idea was copied all over Europe and the United States. Though many were not as financially rewarding to organizers as Rheims, the air show quickly became an established institution. The size of the prizes offered at these competitions reflected the public's interest in aviation. In 1909 nearly half a million dollars were put up as prizes at various shows.

Exhibition Flying at Old Rheinbeck Aerodrome

Though not nearly as dangerous as the airshows of yesteryear, exhibition flying of aircraft from the first decade of flight continues at Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome in Rhinebeck, New York. Founded by Cole Palen to preserve early flight history, the museum features World War I and pre-World War I aircraft in airshows many weekends during spring, summer and fall. For more information about visiting this flying history museum, go to the Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome website.

Soon exhibition teams, often sponsored by an aircraft manufacturer, were put together to tour with the various shows. Even the Wright Brothers fielded an exhibition team. Pilots for these teams could earn immense sums, as much as $1,000 a day, but took incredible risks by pushing themselves and their machines to the limit. Each race seemed to get longer and faster as more and more pilot's lives were claimed in the pursuit of glory and money.

Typical of this era was the challenge to fly the Alps. Italian promoters posted a $14,000 prize for the first aviator to fly though the Simplon Pass, a height of 6,600 feet, which lay between Switzerland and Italy. Thirteen aviators entered the contest, but the race committee only accepted five who seemed to have the best credentials. One of them was a Peruvian aviator named Jorges Chavez Dartnell (who was referred to France as Georges Chavez). In preparation for the flight Chavez took his Bleriot XI up in a test flight 8,487 feet, breaking the current altitude record.

The race opened on September 18, 1910, but Swiss authorities forbade flying as it was a Swiss holiday. The next day the weather turned bad and for the next four days either the Swiss or Italian side of the pass was clouded over. Chavez took his plane up for a look and was tossed about, "The machine, it was like a toy in that wind," he said later.

On September 23, weather cleared and Chavez decided to make an attempt. Slowly his plane climbed to the top of the pass. Witnesses on the ground reported that he seemed to be hanging onto the controls as the wind tossed his craft violently around. He made it through the dangerous, twisting gorges, though, and headed for a landing at the town of Domodossola on the Italian side. As he approached the landing field he gave the Bleriot a little gas to get past a road. Then suddenly it happened. The craft was so weakened by the high winds it failed under the strain. "I saw the two wings of the monoplane suddenly flatten out and paste themselves against the fuselage," a watcher said "Chavez was about a dozen meters up; he fell like a stone." Four days later Chavez, age 23, died of massive internal injuries.

Such fatalities did not seem to reduce the public's interest in flying competitions or shows. It would not be long, however, before airplanes would find uses beyond exhibitions. The Wrights had been trying to sell airplanes to the military almost since they had invented them. Also a stunt by aviator Ralph Johnson at a Boston air meet in 1910 had intrigued military observers. Johnson, using a standard Wright Biplane had made "bombing" runs at a mock battleship using plaster bombs. He scored nine straight hits on the model.

In 1913 stunts took a different turn when Frenchman Adolphe Pegoud, who was nicknamed "the foolhardy one," started experimenting with air maneuvers that previously would have been considered suicidal. First he learned how to fly his airplane upside down and right it again. Then, before an astounded crowd, he took his plan up to 10,500 feet, dove screaming toward the ground, then pulled up to complete an inside loop.

Pegoud wasn't the first to try this maneuver. A month earlier a Russian military flyer named Peter Nesterov had done one just on a lark (and ended up under house arrest for endangering government property). Pegoud was the first though to systematically push the airplane to its acrobatic limits. Pegoud's object wasn't just to create amazing stunts. As he said later, "It seemed important to me to prove to my comrades that they should never believe themselves lost. I would like to say, 'My friends, you have seen me fly upside down; you know that it is possible. Consequently, if the day comes when, in a dive, your plane goes over on its back, let it do it. Deliberately, calmly, take your time and straighten it up, using the controls as if you were flying normally.'"

Aerial acrobatics soon became standard fare at airshows, though they had a dark side. These maneuvers, so well explored by Pegoud would become the standard tools of fighter pilots as the airplane became a military weapon.

The Wright's Patent War

While World War I was still a few years away, the war between the Wright brothers and the rest of the world of aviation was in full swing. The Wrights held patents to key aviation technologies and charged a significant fee for licensing them. Other aircraft builders who did not want to pay the fee had to challenge the Wrights on legal grounds, or find a way to control the aircraft that did not fall under the Wright patent. This second approach led to a string of strange designs many of which flew poorly or not at all.

In 1914 Glenn Curtiss gets Samuel Langley's 1903 aircraft to lift off the water's surface in an attempt to break the Wright's patents.

Curtiss tried a different approach. At about the same time the Wrights were preparing their first aircraft in 1903, Samual Langley (of the Smithsonian Institution) had been working on a plane to be launched from the top a houseboat. During tests it crashed because of a failure of the catapult mechanism designed to launch it. In 1914 Curtiss made an agreement with the Smithsonian to rebuild the craft so that it was identical to the original design to see if it would fly. Curtiss thought that this would show that the Langley craft could have flown before the Wright brothers Flyer did and therefore be used to break their patents. Curtiss did manage to get the craft rebuilt and into the air, but secretly made modifications, including a bigger engine, heavier trussing and changes to the camber of the wings, that made it flyable.

The legal battle continued past Wilber's death at age 45 in 1912. It was effectively ended in July of 1917 when three months after entering World War I the U.S. government forced a pooling of all aircraft patents in the national interest. Orville, who had sold out of the company in 1915, continued to devote his life to aviation serving as an advisor to federal boards and private foundations until his death in 1948.

One decade after invention, airplanes had moved from infancy to adolescence. In the next decade they would pulled in to the very adult world of war.

Read the conclusion of the story on early flight in Part3: The Warbirds

Back to Part 1