"John Peerybingle's Fireside" — Fred Barnard's initial illustration for "The Cricket on the Hearth" in Dickens's "Christmas Books" (1878) (original) (raw)

Passage Illustrated: A Modern "Holy Family"

It was pleasant to see Dot, with her little figure, and her baby in her arms: a very doll of a baby: glancing with a coquettish thoughtfulness at the fire, and inclining her delicate little head just enough on one side to let it rest in an odd, half-natural, half-affected, wholly nestling and agreeable manner, on the great rugged figure of the Carrier. It was pleasant to see him, with his tender awkwardness, endeavouring to adapt his rude support to her slight need, and make his burly middle-age a leaning-staff not inappropriate to her blooming youth. It was pleasant to observe how Tilly Slowboy, waiting inthe background for the baby, took special cognizance (though in her earliest teens) of this grouping; and stood with her mouth and eyes wide open, and her head thrust forward, taking it in as if it were air. Nor was it less agreeable to observe how John the Carrier, reference being made by Dot to the aforesaid baby, checked his hand when on the point of touching the infant, as if he thought he might crack it; and bending down, surveyed it from a safe distance, with a kind of puzzled pride, such as an amiable mastiff might be supposed to show, if he found himself, one day, the father of a young canary. [Household Edition, "Chirp the First," 80]

Barnard's illustration compared to those by Maclise, Doyle, and Leech (1845)

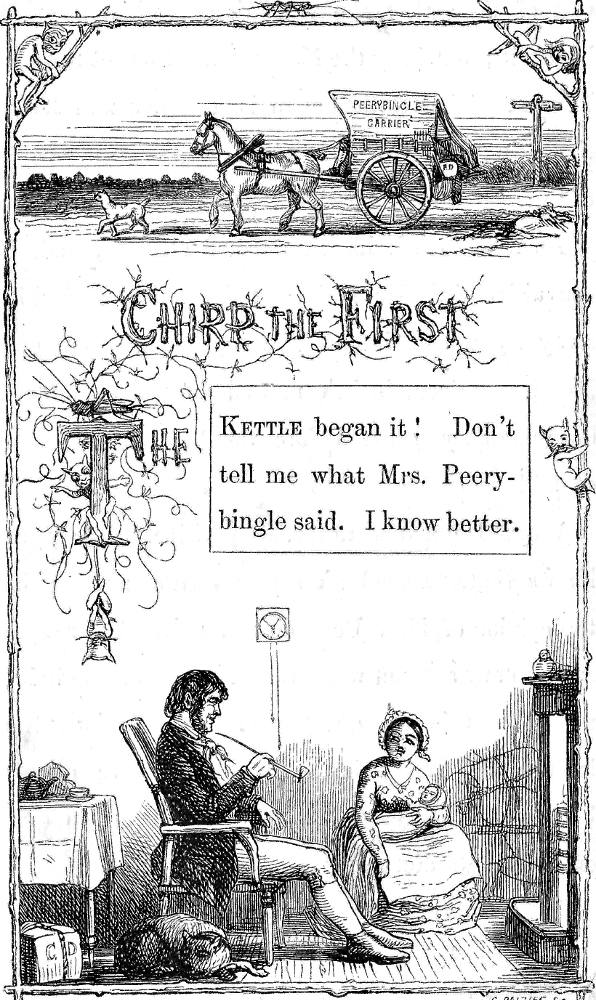

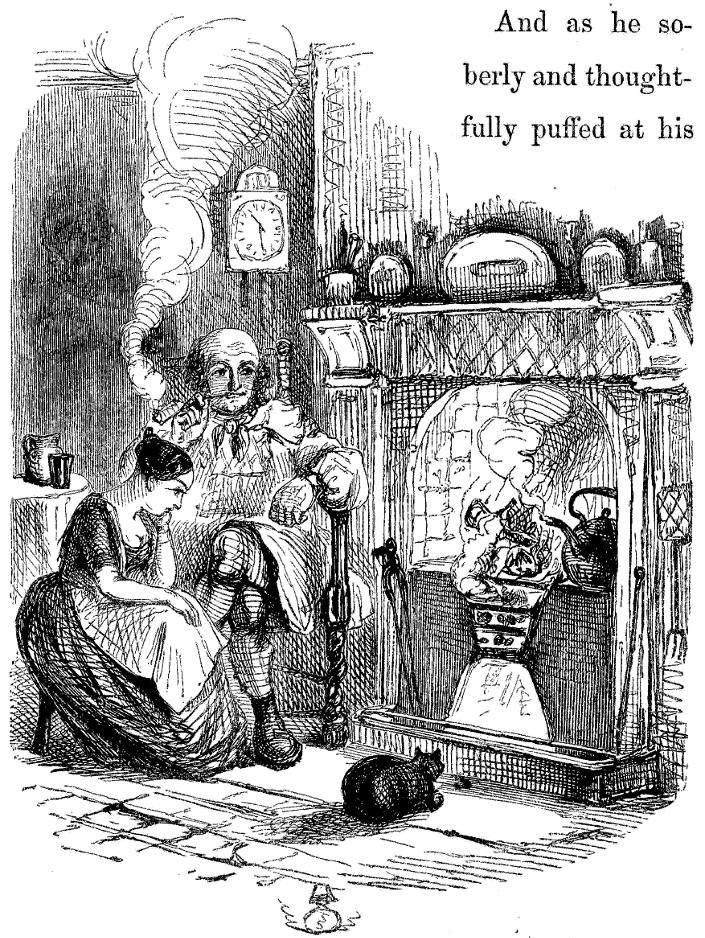

Barnard presents Dot and John Peerybingle as a stereotypical Victorian family before their hearth. His approach, in other words, differs from those chosen by Daniel Maclise, Richard Doyle, and John Leech in the 1845 Bradbury & Evans edition. Although the Chapman and Hall Household Edition of the third A Christmas Carol begins with a highly realistic and modelled treatment of the old carrier, his young wife, infant son, and their adolescent nurse in front of the domestic hearth on a chilly winter evening, the original illustrators provide contrasting treatments of this scene. Maclise offers a pair of highly fanciful realisations of the conclusion of the opening "Chirp," the elegant frontispiece (hand-coloured in some specimens of the book) revealing the fairy vision that John entertains of the future "as he soberly and thoughtfully puffed at his old pipe, and as the Dutch clock ticked, and as the red fire gleamed" (89) of Dots yet-to-be, himself an aged carrier with a pair of sons to run the business, and then "graves of dead and gone old Carriers, green in the churchyard" (89). In contrast, Richard Doyle provides a more prosaic view of the old carrier, smoking his long-stemmed pipe in Chirp the First (see below) in a style established in the second Christmas Book, The Chimes — showing two separate but associated narrative moments simultaneously: above, the carrier's van, accompanied by his dog, Boxer, passes the village finger post as he approaches home at dusk; below, John Peerybingle (in profile) takes his ease before the fire, his tall figure dwarfing those of his wife and child to the right, the faithful Boxer by his chair.

Relevant illustrations from the 1845 and Later Editions

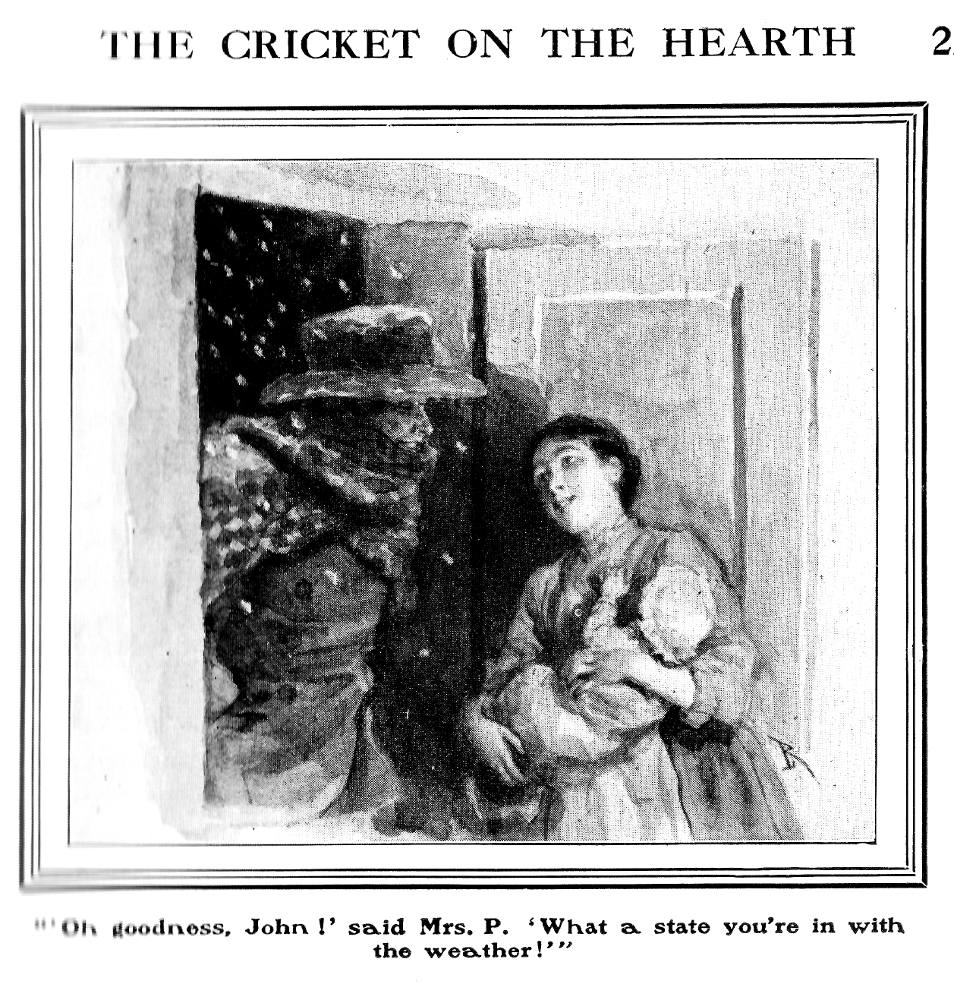

Four illustrations of the opening scene: Left: Maclise's Frontispiece (1845). Centre: L. Rossi's Mr. Peerybingle's Welcome Home (1912) Centre:R. Doyle's Chirp the First (1845). Right: Leech's John and Dot (1845).

Now examine Fred Barnard's 1878 composite woodblock engraving of much greater scale and far less fanciful construction. Gone are the goblins and fairies of 1845, and, in their places, as seen from the fireplace, John supporting his comely wife, holding their infant son as the gawking Tilly Slowboy (left) happily looks on. Barnard's realistic three-quarter-page woodcut synthesizes all of the "Chirp the First" large- and small-scale woodcuts in the 1845 Bradbury and Evans edition, in which the various illustrators repeatedly depict the fireside, the kettle and the cricket, Tilly and the baby, the carrier's van returning home in the darkness, and John and Dot in domestic contentment. Although Dot (Mary) refers to her husband as a "Poor old man" (80), the text reveals that he is in fact only middle-aged (in 1845, Dickens was just 33). Barnard describes John as appropriately robust and genial as he reaches for his pipe, which Dot will then dextrously fill and light. His version of the carrier is consistent with that of Dickens ("rugged," "awkward," and "burly" — and genial). The gangling adolescent nurse, Tilly Slowboy, a foundling, is as Dickens describes her: full of "gaping admiration," "in her earliest teens," and possessing "a spare and straight shape" (80-81) — a devoted and well-meaning "natural" in the tradition of the Comic Woman of Victorian melodrama.

Maclise's lavish fusion of the real and the imaginary is perfectly consistent with the effect at which Dickens seems to have aimed and which Barnard eschews: "Dot resembles a figure in a Christmas puppet show, representing a chubby, prepubescent teenager, playing at keeping house with a painted toy [her "very doll of a baby"]. This pervasive effect of make-believe is one for which Dickens seems to have strived" (Thomas 44). Barnard's markedly realistic style differs markedly from that of Dickens's original illustrators; however, the final plate in "Chirp the First," John and Dot (see below) by the Punch cartoonist John Leech, offered Barnard the most congenial model available. Leech chose not to make the Baby the focal point of the but focuses on the husband and wife. He emphasizes John's age (by his balding pate) and his rustic and working-class affiliations (as suggested by his linen smock frock). In contrast, Barnard concentrates on fashioning the family members into a cohesive unit, with the line of their heads pointing down and right from Tilly above to Boxer below. Leech crowds the elderly husband and young wife into the left-hand frame in order to focus on the familial hearth, with its cheerful coal fire and steaming kettle, the rising fumes from which are repeated in the cloud of white smoke issuing forth from John's pipe. Had he followed the text more closely, Barnard whould have depicted John wearing his "outer coat" as he reaches for his pipe, but he had to satisfy only himself and not the keen-eyed Dickens, who was often overly scrupulous about such details. Whereas Leech is as much interested in the bric-a-brac of the mantelpiece as he is the characters, Barnard omits or barely sketches in these extraneous details in order to focus on the closeness of the relationship between the devoted husband, the happy wife-mother, and infant — the last element entirely missing from Leech's illustration. The Household Edition illustrator has shifted the viewer's perspective from the doorway of the parlour (affording an ample view of the fireplace and kettle that Dickens emphasises in "Chirp the First") to that of the hearth itself. We do not need to see the hearth, but its effect on the family members.

Although Leech, who focuses upon the carrier's comfortable parlour, omits the comic nurse and the faithful dog, Barnard created the image of a Victorian pater familias on his throne. The dynamic John reaches into his pocket for his pipe and interacts with his wife and child (their heads in close proximity suggesting their emotional bond); his queenly wife is neither a nondescript female of indeterminate age, as are Doyle's and Stanfield's, nor the slender adolescent of Leech, nor yet Dickens's "coquettish" child-bride, Instead we see a mature woman, her matronly cap functioning as her crown of domestic authority. Thus, Barnard emphasizes the alertness and activity of his figures and their equality within the family unit, rather than the disparity in the ages of the couple. In this regard, then, Barnard's interpretation of the Peerybingles is closest to that of Maclise in his ornamental frontispiece, although Maclise's realistically modelled couple are ornamental figures seen in profile, isolated and static, as the Baby sleeps in his cradle, rocked vigorously by exuberant fairies, and John and Dot have withdrawn into themselves, half-asleep. This, then, is the tranquil domestic establishment about to be shaken by the husband's (and the reader's) fears of disloyalty and infidelity. Barnard conveys his sense of cosy domesticity not as the accumulation of things but as the closeness, both physical and emotional, of all members of the family, including the cat and dog, all of whom he individualises and treats with conviction.

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and his Original Illustrators. Columbus: University of Ohio Press, 1980.

Cook, James. Bibliography of the Writings of Dickens. London: Frank Kerslake, 1879. As given in Publishers' Circular The English Catalogue of Books.

Dickens, Charles. The Cricket on the Hearth. A Fairy Tale of Home. Illustrated by John Leech, Daniel Maclise, Richard Doyle, Clarkson Stanfield, and Edwin Landseer. Engraved by George Dalziel, Edward Dalziel, T. Williams, J. Thompson, R. Graves, and Joseph Swain. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1846 [December 1845].

_____. The Cricket on the Hearth. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book, 1912.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Parker, David. "Christmas Books and Stories, 1844 to 1854." Christmas and Charles Dickens. New York: AMS Press, 2005. 221-282.

Patten, Robert L. Charles Dickens and His Publishers. University of California at Santa Cruz. The Dickens Project, 1991. Rpt. from Oxford U. p., 1978.

Slater, Michael. "Introduction to The Cricket on the Hearth." Dickens's Christmas Books. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1971. Rpt., 1978. II: 9-12.

Slater, Michael. "Notes to The Cricket on the Hearth." Dickens's Christmas Books. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1971. Rpt., 1978. II: 363-364.

Solberg, Sarah A. "'Text Dropped into the Woodcuts': Dickens' Christmas Books." Dickens Studies Annual 8 (1980): 103-118.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Created 28 March 2001

Last modified 5 April 2020